#hans holbein

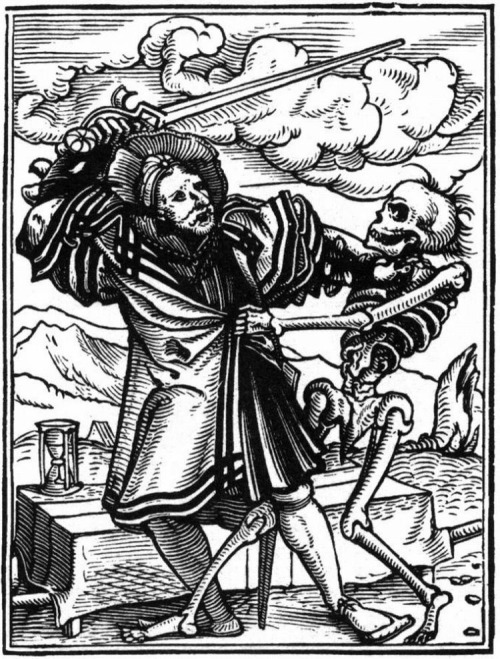

Credit: Hans Lützelburger (German, 1495?-1526) after designs by Hans Holbein the Younger (German/Swiss, 1497/8-1543). Images of Death, c. 1526, woodcuts. Details from Creation of Eve and Fall (Temptation of Adam) including canine representation. I am not sure how a dog could be present at the creation of Eve. As seen at the exhibit “Holbein: Capturing Character” at the Morgan Library & Museum @themorganlibrary in New York.

The Ambassadors[1533]

- Featuring an anamorphic skull in foreground of painting. Fantastic 16th century work in perspective.

Artist: Hans Holbein the Younger

Post link

ca. 1416 statue of Jeannede Boulogne, Duchess of Berry (c.1378-c.1424), by Jean de Cambrai (d.1438), currently situated in the Bourges Cathedral

source1,source2(bylouis.foecy.fr on Flickr)

source3(by Philippe_28 (maintenant sur ipernity) on flickr)

1523-4 drawing of the same by Hans Holbein the Younger

source (wikimedia commons)

Post link

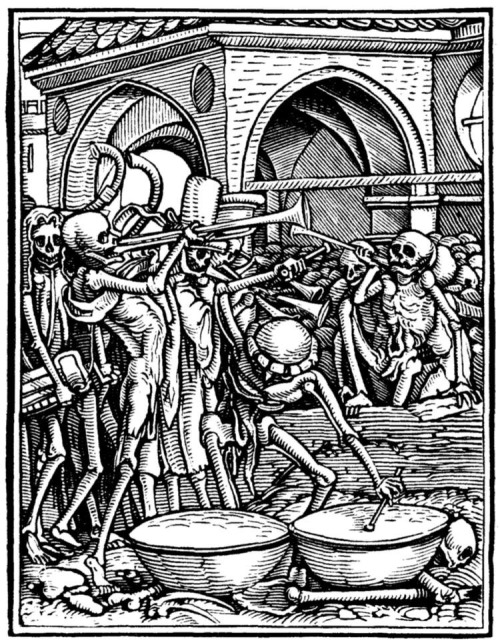

“Holbein’s dance of death alphabet was first used in August 1524. The alphabet was originally published as sheets with Bible quotes.” This is a video of what the alphabet may have looked like with the letters removed and paired with their respective Bible quote.

Hans Holbein’s Dance of Death alphabet (Part 3). There are 24 letters since i,j and u,v are the same:

V. The Rider

W. The Hermit

X. The Gamblers

Y. The Baby

Z. Judgement Day

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Post link

Hans Holbein’s Dance of Death alphabet (Part 2). There are 24 letters since i,j and u,v are the same:

K. The Nobleman

L. The Canon

M. The Physician

N. The Rich Man/Miser

O. The Monk

P. The Soldier

Q. The Nun

R. The Fool

S. The Young Girl

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Post link

Hans Holbein’s Dance of Death alphabet (Part 1). There are 24 letters since i,j and u,v are the same:

A. Bones of All Men

B. The Pope

C. The Emperor

D. The King

E. The Cardinal

F. The Empress

G. The Queen

H. The Bishop

I. The Duke

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Post link

HUMANIST PORTRAITURE IN RENAISSANCE ENGLAND

As Lord High Chancellor of England, the humanist scholar and author Sir Thomas More was the highest ranking official of King Henry VIII’s court and one of the wealthiest men in England. In 1527, More commissioned Henry’s Swiss court artist, Hans Holbein the Younger, to paint a group portrait of his extended family. The monumentally-scaled picture, depicting 12, highly-individualized figures in a unified spatial setting, executed in deep, jewel-like colors, set a new standards of invention, complexity and quality hitherto unparalled in English panel painting.

Holbein placed More at the center of the composition. His father, the judge Sir John More, is seated to More’s right and his only son, John, stands to his left. Just beyond the family’s patrinlineal core, is Holbein depicts More’s daughters: Elizabeth Daunce attends to Sir John, while Cecily Heron and Margaret Roper are seated at right. More’s second wife, Lady Alice More, is seated at the far right. Her daughter from her first marriage, Margaret Giggs, stands at the far left. Anne Cresacre, of Sir Thomas and future wife of John, stands behind the Sir John. Also included in the portrait are the household ‘fool,“ Henry Patenson, in orange, and More’s clerk John Harris. All figures are identified by Latin inscriptions.

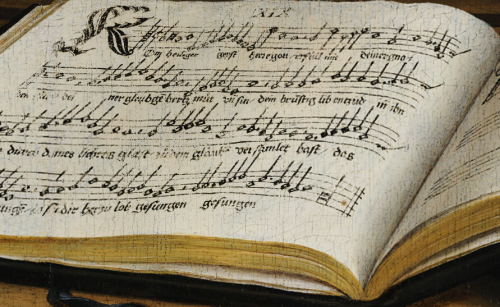

More’s wife and children all hold books. Some are shown reading, while others pause to reflect with their books either open or mark their place with a finger. The clerk, entering from the right, carries a scrolled document, no doubt intended for Sir Thomas. More books and musical instruments are displayed on a shelf and a large pendulum clock hangs on the rear wall. As he would later do in The Ambassadors, Holbein conspicuously represents these objects to emphasize the literate and learned humanist culture of More’s household. An advocate of the education of women, More educated his wife, daughters, and son in the same liberal arts cirriculum. The panel’s latin inscriptions would have posed problems for no members of the family. Margaret Roper’s mastery as a translator of Greek and Latin was widely acknowledged by More’s humanist peers, including Erasmus.

The deeply-pious More had briefly entered a Carthusian monastery prior to embarking on his political career and his profound Christian belief influenced his theories of humanist education. Margaret is therefore seen reading Seneca’s Œdipus, while Elizabeth carries his Epistolae under her arm. These texts, along with The Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius, seen on a table, represent ancient Stoic philosophy held to be compatible with Christian values. Further indications of the family’s Christian piety include the crucifix worn by Patenson, the rosary worn by Margaret, and the red cross suspended from Elizabeth’s choker. Flowers associated with the Virgin Mary – lilies, carnations, columbine, iris and peony – are displayed in vases around the room.

Painting served an important purpose in More’s learned circle. In 1517, his friends and collaborators Erasmus and the scholar-editor Pieter Gillis (one of the dialogic participants in More’s Utopia), commissioned Quentin Matsys portraits of themselves, showing them at work in their studies, as gifts for More as tokens of their intense intellectual bond.

More’s resistance to Henry VIII’s ecclesiastical policies led to his execution in 1536. His family portrait survived, with several later additions and alterations, until it was destroyed in a fire in 1752. Today, it is known through two 16th-century copies and Holbein’s exquisite preparatory drawings.

Hans Holbein the Younger, Sir Thomas More, c. 1527, Windsor Castle, Royal Collection; Hans Holbein the Younger, Study for the More Family Portrait, 1527, Basel, Kunstmuseum; after Hans Holbein the Younger, Margaret More Roper, 16th c, Knole, National Trust; after Hans Holbein the Younger, Lady Alice More, 16th c., Private Collection; Hans Holbein the Younger, Elizabeth More Daunce, c. 1527, Windsor Castle, Royal Collection; Hans Holbein the Younger, Anne Cresacre, c. 1527, Windsor Castle, Royal Collection; Hans Holbein the Younger, Margaret Giggs Clement, c. 1527, Windsor Castle, Royal Collection; Hans Holbein the Younger, John More, c. 1527, Windsor Castle, Royal Collection; Rowland Lockey after Hans Holbein the Younger, More Family Portrait, 1592, Nostell Priory, National Trust; Hans Holbein the Younger, Sir John More, c. 1527, Windsor Castle, Royal Collection; Hans Holbein the Younger, Cecily More Heron, c. 1527, Windsor Castle, Royal Collection; Quentin Matsys, Erasmus of Rotterdam, 1517, London, Royal Collection Trust; Quentin Matsys, Petrus Egidius, 1517, Antwerp, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen.

Some of you may remember how opposed I was to the “new portrait of Anne Boleyn” that surfaced a few months back. A new miniature portrait was brought to my attention via Facebook today, and I wanted to tell you why I think this one actually could be a portrait of Anne Boleyn, or at least a copy of a portrait of her.

The owner of the portrait wrote in her post:

Last year my husband purchased various snuff boxes etc at a local auction. In amongst them was a small portrait. I took the portrait out of its leather and velvet lined box and written on the back was written A Bo…. ( or A Bu….) and on the next line AD 1530. There is also a date at the bottom which appears to be 1796. I have been advised that it is probably not by a professional artist and that it is based on a print held by the British Museum from the early 1800’s but it is dated earlier than that. It probably is based on another portrait. What there is no doubt of it is very similar to other supposed pictures of Anne Boleyn. Also, that in 1796, over 200 years ago, the artist probably believed this was Anne Boleyn?

The date “1530″ on the rear was probably the artist’s guess as to the year the original image was created, but is probably just that - a guess. If the image does portray Anne in 1530, it would be two years before she married Henry VIII.

Unlike the portrait of Lady Bergavenny, the sitter in this portrait is wearing the appropriate clothing and jewelry for a woman of Anne Boleyn’s time-period and station. I would suggest that the date is closer to 1535 than 1530, though, simply because of the shortness of the lappets.

The headdress closely resembles the one worn in Anne’s Nidd Hall and portrait medallion images.

The lappets on the hood reach to about mouth-level which would be correct for the mid 1530s.

The date on the back of the portrait is difficult to distinguish (at the bottom of the frame) but 1796 seems correct, stylistically speaking.

As to what portrait the miniature may be based from, I suggest possibly this one by Jacobus Houbraken, 1738.

But what makes it intriguing to me is that the Houbraken etching was supposedly done after a Holbein portrait. I’d like to fantasize that the artist was actually looking at the Holbein painting itself when they made this miniature copy, and not this etching! Could we possibly be getting glimpses of the lost full-length Holbein of the queen which was lost in the late 18th century?

One last thing… Note the hair of the sitter. It’s the same shade as that seen in Elizabeth’s portrait ring of her mother.

Yes, I’m still an advocate of the Anne Boleyn Was a Redhead school! And it’s interesting the artist would choose to give her hair this shade if they were simply inventing colors for the black-and-white etching above. More fuel for my fantasy that the artist actually saw the lost Holbein!

Post link

![The Ambassadors [1533]- Featuring an anamorphic skull in foreground of painting. Fantastic 16th cent The Ambassadors [1533]- Featuring an anamorphic skull in foreground of painting. Fantastic 16th cent](https://64.media.tumblr.com/419d7596b9611b1d6776951b4365c008/f566370abaaac4d3-8c/s500x750/ac8f6ef219be8ef55686ed31207beceb921552e7.jpg)