#jamee pritchard

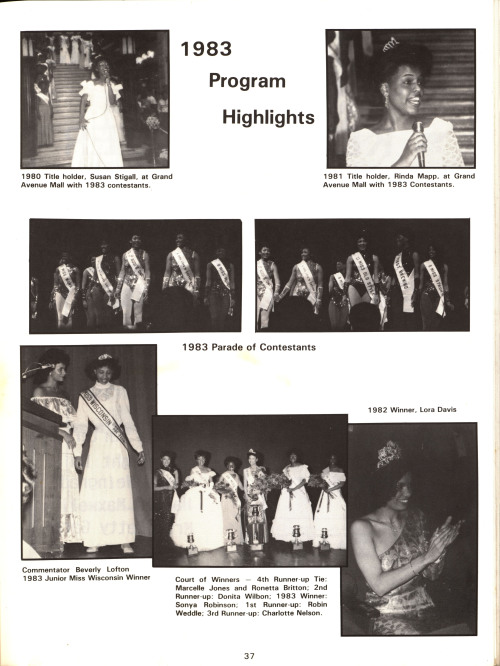

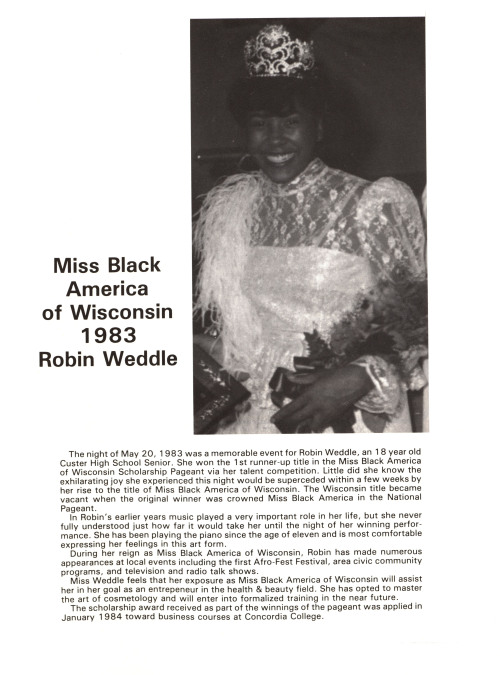

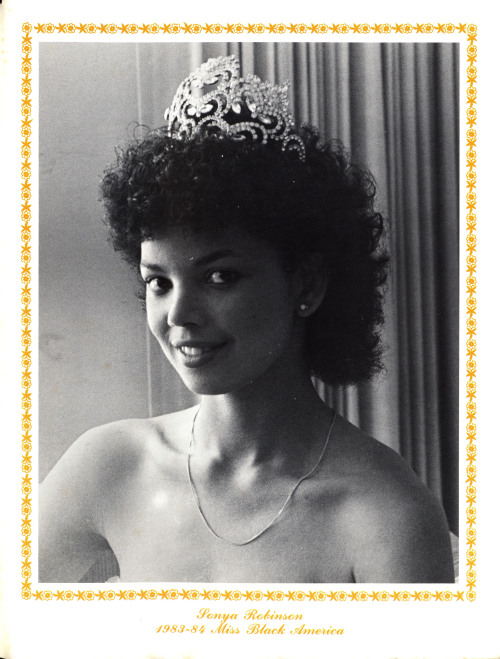

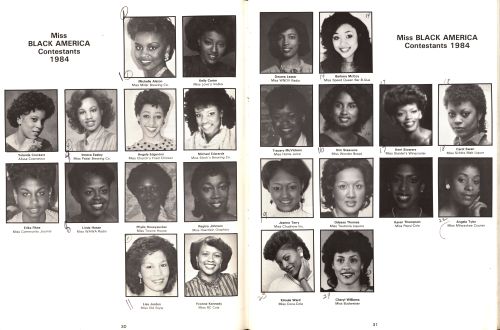

Miss Black America of Milwaukee

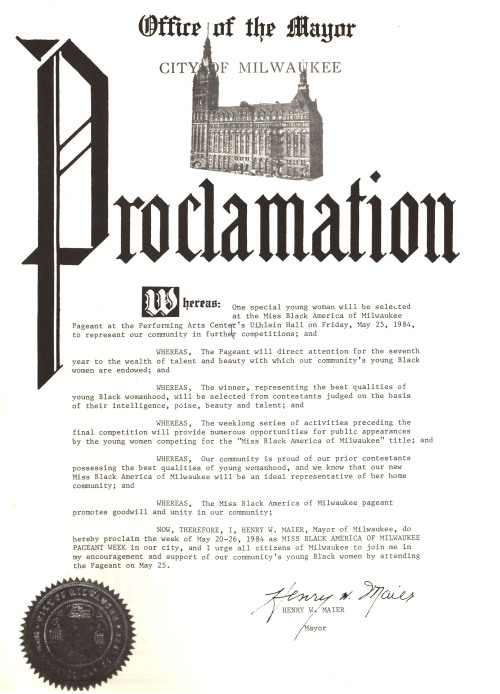

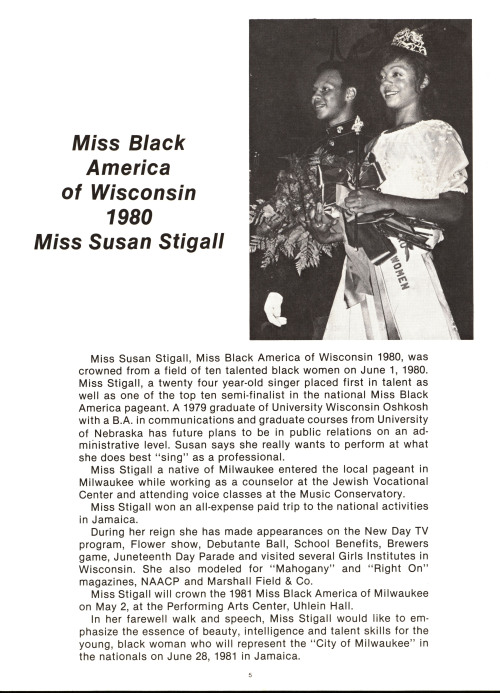

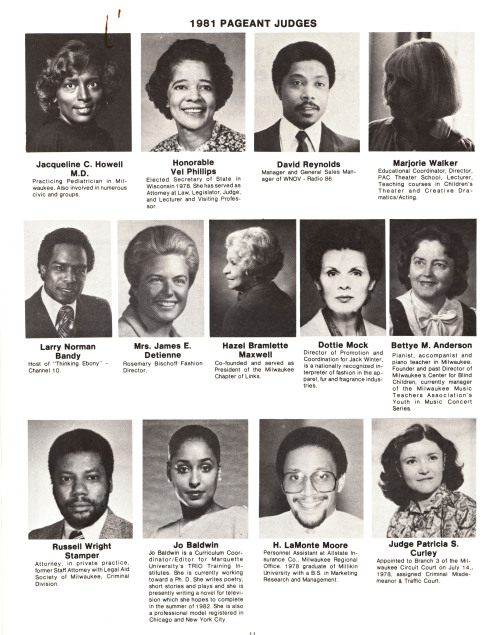

In 1981 and 1984, Vel Phillips was a judge for the Miss Black America of Milwaukee pageant. These pageant programs are from her personal papers at UWM Archives: Milwaukee Mss 231, Box 82, Folders 13 and 14.

The national competition, Miss Black America, started in 1968 in Philadelphia as a protest against the exclusion of Black women in the Miss America pageant. With the support of the NAACP, the pageant received nationwide press coverage and was televised in 1977, the year of Milwaukee’s first competition. According to Mayor Henry Maier’s 1984 proclamation, winners were chosen for representing “the best qualities of young Black womanhood” and were judged “on the basis of their intelligence, poise, beauty, and talent.”

Susan Wells and Sonya Robinson (pictured above), both contestants of Miss Black America of Milwaukee, went on to win the national title of Miss Black America in 1982 and 1983, respectively.

Miss Black America disrupted the rhetoric that shaped women’s beauty standards of the 1960s and 1970s and proved to Black women and girls that their Blackness was indeed beautiful. The pageant continues today, celebrating more than 50 years of Black beauty, culture, and identity.

- Jamee, Archives Graduate Intern

Post link

In 1963, Waukesha Freeman Printing Company refused to print four poems for the winter edition of Cheshire, a UWM student literary magazine. The printer claimed that the poems were obscene and would print them only with the consent of the University. UWM’s administration, however, felt it was not their place to censor student publications, as is noted in the below letter from Provost J. Martin Klotsche to Dean Robert Morris.

As the letter references, the Cheshire case was referred to the Student Life and Interest’s sub-committee on publications (SLIC), but several members of that committee insisted that they did not want to become a censorship board and refused to make a decision about the publication of the four poems.

University administration continued its internal debate of the issue. Fred Harvey Harrington, the president of the UW-Madison, wrote:

He concludes his letter with one further point:

“Pornography problems will be with us again. So perhaps one of us (maybe Martha) should work on the problem some, and help us set some guide lines. Will you try, Martha?”

In her response to Harrington’s letter, Dean Martha Petersen agrees to look into the issue but with some caveats.

Dean Petersen’s letter highlights a key issue. How does the University shape its relationship with students? Is it an agency of authority or an agency of help and support? In the Cheshire case, University administration decided to take a neutral ground rather than censor its students, and ultimately, without consent from the Provost or SLIC, Freeman Printing Company did not print the poems.

TheCheshire staff, however, still included the poems as an insert in their winter 1963 edition with an explanation of each author’s intent by the editor, Robert Christeck.

The Four Poems in Question:

“Meanwhile Back in the Jungle” by S.B. Smith

“Anti-poem” by Peter Brunner

“Bullfight” by Bill Olsen

“Imagine This Thing” by Bill Olsen

To read more into the Cheshire Obscenity Case, refer to UWM Archival Collection 46, Box 6, Folder 19. If you would like to read through copies of the Cheshire magazine from 1931-1968, visit our reading room (call number: LH 1.C4 volumes 1-37).

-Jamee, Archives Graduate Intern

In 1918, Harold O. Berg, supervisor of theMilwaukee School Board Extension Department, published this 23-page booklet called “Practical Aids in Conducting a Neighborhood Recreation Center.” It offers suggestions to directors of recreation centers on how to conduct a range of social activities that include basketball and indoor baseball, quiet game rooms, dancing classes and socials, and library readings rooms. As is noted at the start of the booklet, recreation centers played a major role in Milwaukee because recreation was recognized as an essential aspect of education.

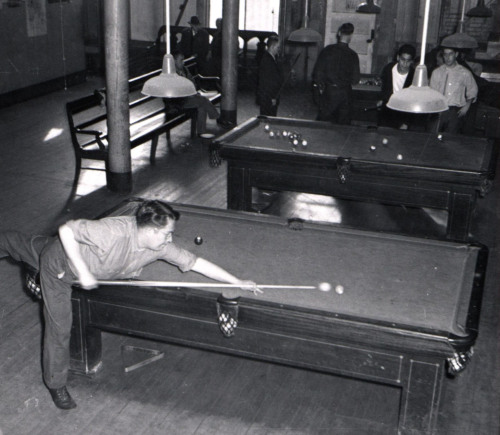

The city’s Municipal Recreation and Community Education program was established in 1911 and the first two social centers, operated from Milwaukee schoolhouses, were opened in 1912. By 1948, forty social centers were in existence in all areas of Milwaukee, and they offered more than one hundred different activities that included drama clubs, music organizations, athletics, games, club activities, and arts and crafts. Many of those activities followed the gender norms of the time, as is noted in the photographs. The women and girls from the Forest Home Social Center are pictured at cooking and dancing classes (dated 1900-1930), while their male counterparts at 923 Market Street are pictured playing checkers and billiards (dated 1954).

Most of the work of the Extension Department was on behalf of young people, 17-23 years old, who fell outside of the regular school system and who typically worked during the day and had increasing amounts of leisure time at night. In essence, one of the major goals for Milwaukee’s social centers was keeping young people occupied and out of trouble.

More information and photographs of Milwaukee’s recreation history can be found at UWM Archives in the Milwaukee Public Schools, Department of Municipal Recreation and Community Education Scrapbooks collection, 1923-1989.

“Practical Aids in Conducting a Neighborhood Recreation Center,” along with the photographs from the Forest Home and 923 Market Street social centers, are available in Box 36 of the collection.

Call number: UWM Manuscript Collection 151

-Jamee, Archives Graduate Intern

Post link

“Faster, Higher, Stronger”

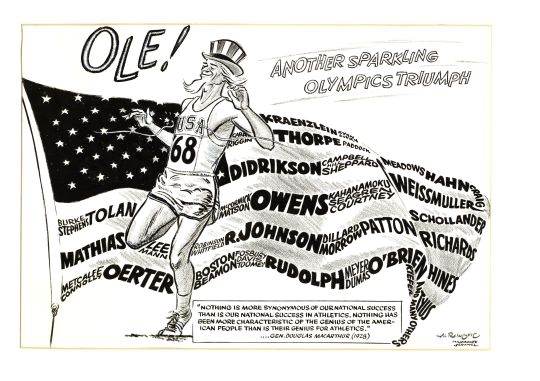

To highlight the start of the 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo, we again dig into the Albert Rainovic collection at UWM Archives, call number UWM Manuscript Collection 43.

Pictured above is an image drawn by Rainovic that was published in the “Men’s and Recreation Section” of The Milwaukee Journal on Sunday, November 18, 1956. Find this image in Box 14, #459.

Clockwise, the featured Wisconsin athletes include Ken Wiesner, Del Lamb, Ralph Metcalf, and Don Gehrmann. The following caption is included with the image:

Track and skating have provided Wisconsin with most of her Olympic stars, such as these from the last quarter century. Gehrmann ran eighth in the 1948 1,500 meter race. Wiesner placed second in the high jump in 1952. Lamb came in fifth in 1936 and tied for sixth in 1948 in 500 meter races. He was coach of the 1956 speed skating team. Metcalfe took second in the 100 meter dash and third in the 200 in 1932. He ran second to Jesse Owens in the 100 in 1936. - By Al Rainovic, a Journal Artist

In1968, the Olympics Games were in Mexico City, Mexico, and Rainovic drew the above image to commemorate the event. Uncle Sam is drawn in a track and field uniform with the American flag in the background, and on the flag, are surnames of U.S. Olympians. This image was published in the Milwaukee Journal on October 25, 1968. The quotation reads:

“Nothing is more synonymous of our national success than is our national success in athletics. Nothing has been more characteristic of the genius of the American people than is their genius for athletics.”

- Gen. Douglas MacArthur (1928)

What Rainovic’s drawing does not capture amid the national triumph of Olympic gold, is the protest of Black American athletes during the 1968 Games. In what is now an iconic image (pictured below), Tommie Smith and John Carlos, sprinters in the men’s 200-meter race, raised their gloved fists in the Black Power salute during the U.S. national anthem. The gesture was done in solidarity with the Black Freedom Movement in the U.S. and was rewarded with the expulsion of Smith and Carlos from the Games because their action was deemed too political for the apolitical nature of an international sports competition, according to the president of the International Olympics Committee (IOC).

Smith, Carlos, and Australian sprinter Peter Norman also wore patches during the medal ceremony that supported the Olympic Project for Human Rights, an organization that protested against racial segregation in the United States and racism in sports.

Find Rainovic’s 1968 drawing in Box 14, #448.

Jamee, Archives Graduate Intern

Post link