#laid-in material

More highlights from our file of “Things Found in Library Books!”

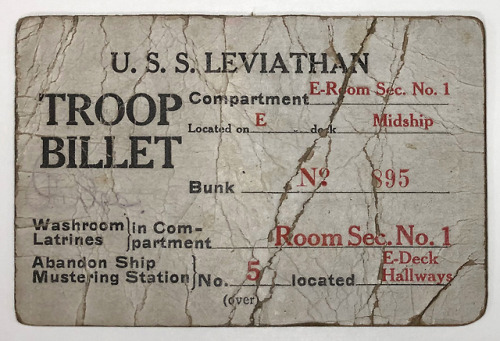

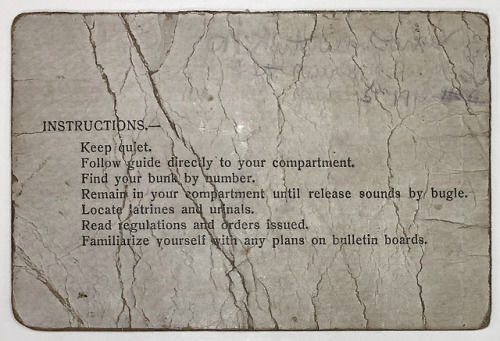

One interesting piece from this collection of orphaned ephemera is a troop billet card for the U.S.S. Leviathan, a massive German-built steamship seized by the United States in 1917 and used as a troop transport during World War I. While we can’t quite make out the name penciled on the back of the card, we can (just barely) read the annotation below, which allows us to date this particular voyage:

Left New York Harbor

June 15th 1918

Can anyone read the name of the soldier in bunk #895? While we can’t say for sure if the former owner of this card made it home from the War, the fact that the card survived gives us some hope.

During its tenure as a military transport, the Leviathan ferried over 119,000 American troops between the United States and Europe. After the War ended, the ship was refitted again to serve as a passenger liner for the United States Lines, and continued to sail across the Atlantic for another 20 years.

Post link

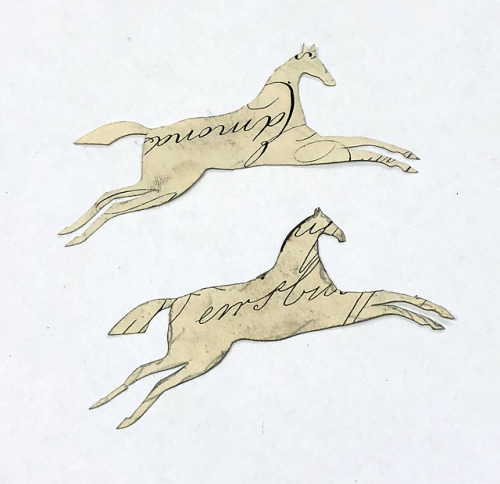

There’s a lot more to studying provenance than deciphering arcane inscriptions and other marks of ownership. Sometimes previous owners will leave other traces of themselves behind, like these loose items we’ve found stuck between the pages of many of our old books.

These pieces of ephemera, or transitory materials originally meant to be discarded after a few uses, have survived against all odds — in some cases for over 100 years — as forgotten bookmarks, safely tucked away and waiting for our librarians or catalogers to stumble across them.

Unfortunately, these particular ephemera are orphaned materials, their original sources unknown or undocumented. Where they might have come from, what books they were originally found in — these remain mysteries that we will probably never solve. But while their usefulness as pieces of provenance evidence is likely nonexistent, these fragile, rarely-preserved fragments of another time and place are still interesting in their own right.

Post link

We’ve probably all done this before. While out and about, perhaps while traveling or shopping, we lay a scrap of paper inside a book. Maybe it’s a receipt for the book’s purchase, or perhaps it’s a plane ticket. Whatever it is, we probably don’t give it much thought at the time. But decades later, or even centuries, those scraps of paper can prove more fascinating than the host book itself.

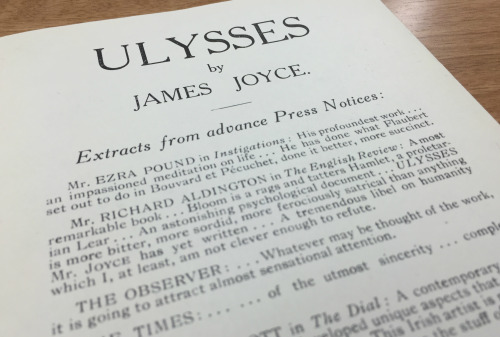

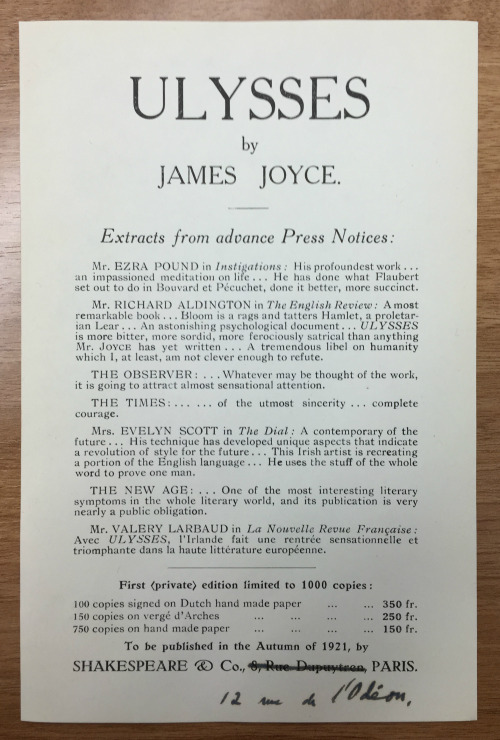

Not to discount Robert McAlmon’s first book, Explorations, but what we found laid inside our 1921 first edition was far more interesting: an early advertisement for Ulysses (as it happens, McAlmon edited Joyce’s Ulyssesmanuscript).

Early press for Ulysses more commonly manifests as a four-page prospectus that included a detachable order form. There were two versions of this that indicated Ulysses would be published in “Autumn of 1921”—just like our single-leaf advertisement (the book was finally published in 1922). One of these prospectuses bore the earlier address of Shakespeare & Co., 8 rue Dupuytren. The second of these prospectuses bore the new address, 12 rue de l’Odéon. Our advertisement here has the earlier address, though corrected by hand (someone please tell us if it’s Sylvia Beach’s hand!) to reflect the new rue de l’Odéon address. So with a bit of sleuthing and some help from The Poetry Collection at the University at Buffalo, we can confidently suggest that this rare Ulysses ad was printed about the same time as the first prospectus.

As you might expect, printed ephemera aren’t known for their survival skills. WorldCat locates two other copies of this particular ad, one each at Yale and Cornell. Surely there are others out there, safely filed away in archival collections—or perhaps just languishing inside an old book, a forgotten memento of a visit to a Paris bookstore in 1921.

~Patrick

This Provenance Project guest post was written by Patrick Olson, Rare Books Librarian at MSU Special Collections. Patrick joined Michigan State University in 2014, having previously held special collections positions at the University of Iowa, MIT, and the University of Illinois, where he also earned his MLIS. Prior to becoming a librarian, he spent four years working in the rare book trade.

Post link