#msulibraries

Today, April 23, is Shakespeare’s birthday! Maybe. Supposedly. It was certainly the date of his death in 1616, but it also commonly celebrated as the date of his birth, some 52 years earlier in 1564.

Several editions of the Bard’s works were printed before his death, but the most complete and most famous collections of his plays are the large folio editions, produced posthumously.

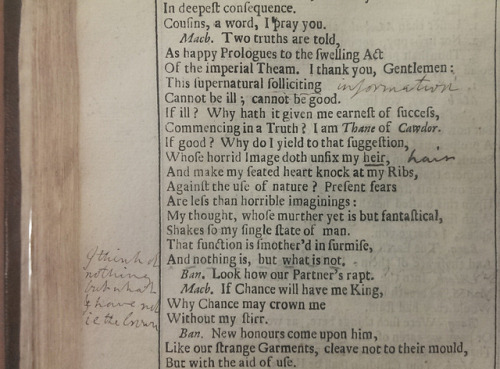

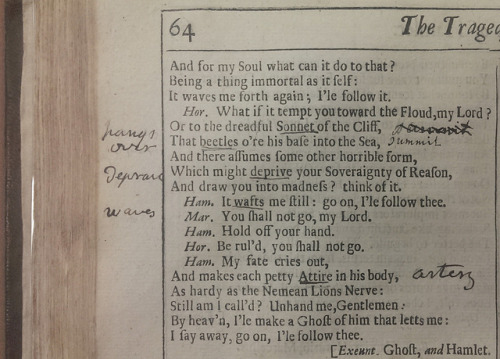

While these beautiful and rare 17th century Shakespeare folios are a significant improvement over the earlier “bad” quarto versions, they are far from perfect copies of Shakespeare’s works.

In the case of own Fourth Folio, it appears as though a previous owner sought to correct some of the numerous typographical errors throughout the volume. Our dutiful annotator has also added several marginal notes commenting on various passages in the text.

Some of these typos really change the meaning of the text in humorous ways:

If good? Why do I yield to that suggestion,

Whose horrid image doth unfix my heir [hair]

- Macbeth, Act I, Scene 3

What if it tempt you toward the Floud, my Lord?

Or to the dreadful Sonnet of the Cliff [summit]

- Hamlet, Act I, Scene 4

My fault is past. But oh, what form of Prayer

Can serve my turn? Forgive me my foul Mother [murther/murder]

- Hamlet, Act III, Scene 3

All those bored scholars with nothing better to do than overanalyze Shakespeare’s works looking for hidden messages should have a field day with some of these passages.

Post link

Reveries of a Bachelor

Though very few modern readers would recognize the name of Donald Grant Mitchell, his collection of sentimental vignettes, Reveries of a Bachelor (written under the pseudonym “Ik Marvel”) was one of the most popular novels of the Victorian era. It was a favorite of Emily Dickinson, and has even been compared to Uncle Tom’s Cabin in its popularity and influence.

Aside from serving as U.S. consul to Venice from 1853 to 1854, Mitchell (1822-1908) spent much of his career writing at Edgewood, his estate near New Haven, Connecticut. Portions of Reveries of a Bachelor first appeared in the Southern Literary Messenger in 1849, and then in 1850 it was published in book form, going through dozens of editions in the following decades. Excerpts were even reprinted by insurance companies and the makers of tonic medicines to be distributed to potential customers.

The text itself is divided into four “reveries” in which a bachelor contemplates boyhood, marriage, country life, travel, and even the phenomenon of dreaming itself. Chapters include “Smoke – signifying doubt,” “Blaze – signifying cheer,” and “Ashes – signifying desolation.”

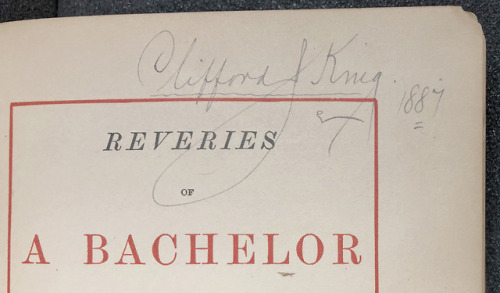

We were fortunate enough to have recently acquired a fascinating copy of the 1886 New York edition of Reveries of a Bachelor. Our copy was originally purchased in 1887 by Clifford Julius King (1865-1910), an Ohio attorney who practiced in Ashtabula (as King did not marry until 1891, he was still a bachelor himself when he bought the book). King had more than just a passing interest in books, as he was a member of the Rowfant Club, an organization for bibliophiles founded in 1892 in Cleveland and still active today.

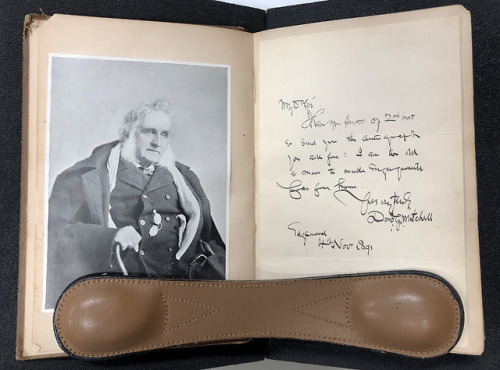

King is presumably responsible for several other characteristics that make this copy stand out. First is a signed letter by Mitchell, perhaps written to King, pasted into the volume along with two portraits of the author. The letter reads:

My dr. Sir –

I have yr favor of 2nd inst

to send you the autograph

you ask for: I am too old

a man to make engagements

far from home.Yrs vry truly,

Dond. G. MitchellEdgewood 4th Novr. 1891

Additionally, an artist known only by the initials B.K.C. has contributed numerous pen and ink wash illustrations to this copy, some of which bear an 1887 date. In total, there are seven full-page images, 17 head and tail vignettes, and 73 marginal illustrations. These drawings really bring Mitchell’s text alive, and the marginal vignettes especially heighten the dream-like aspect of the book, depicting subjects such as a hand lighting a lamp, a foot entering a shoe, or the floating head of a woman.

Though it is not explicitly stated, it is likely that Clifford Julius King, due to his bibliophilic interests, was responsible for embellishing this copy by collecting the Mitchell paraphernalia and assembling it together with the illustrated text. The result is a copy of Reveries of a Bachelor that is truly unique — and truly special!

http://catalog.lib.msu.edu/record=b12953883~S39a

Post link

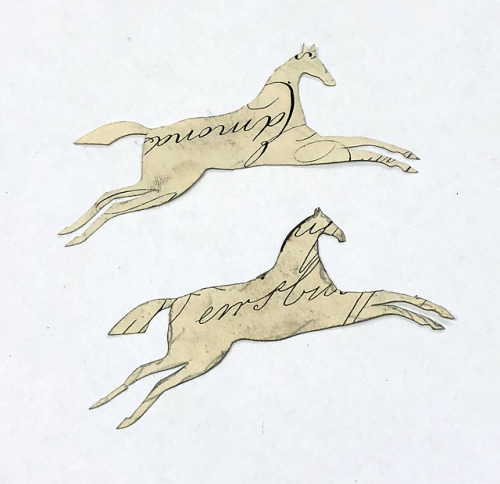

More highlights from our file of “Things Found in Library Books!”

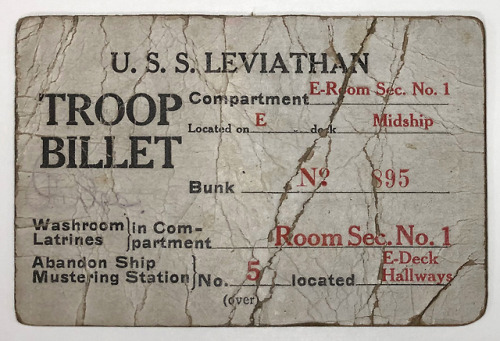

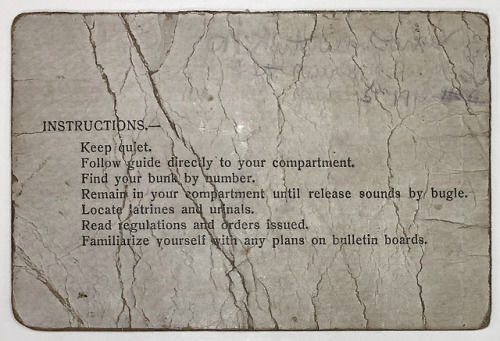

One interesting piece from this collection of orphaned ephemera is a troop billet card for the U.S.S. Leviathan, a massive German-built steamship seized by the United States in 1917 and used as a troop transport during World War I. While we can’t quite make out the name penciled on the back of the card, we can (just barely) read the annotation below, which allows us to date this particular voyage:

Left New York Harbor

June 15th 1918

Can anyone read the name of the soldier in bunk #895? While we can’t say for sure if the former owner of this card made it home from the War, the fact that the card survived gives us some hope.

During its tenure as a military transport, the Leviathan ferried over 119,000 American troops between the United States and Europe. After the War ended, the ship was refitted again to serve as a passenger liner for the United States Lines, and continued to sail across the Atlantic for another 20 years.

Post link

There’s a lot more to studying provenance than deciphering arcane inscriptions and other marks of ownership. Sometimes previous owners will leave other traces of themselves behind, like these loose items we’ve found stuck between the pages of many of our old books.

These pieces of ephemera, or transitory materials originally meant to be discarded after a few uses, have survived against all odds — in some cases for over 100 years — as forgotten bookmarks, safely tucked away and waiting for our librarians or catalogers to stumble across them.

Unfortunately, these particular ephemera are orphaned materials, their original sources unknown or undocumented. Where they might have come from, what books they were originally found in — these remain mysteries that we will probably never solve. But while their usefulness as pieces of provenance evidence is likely nonexistent, these fragile, rarely-preserved fragments of another time and place are still interesting in their own right.

Post link

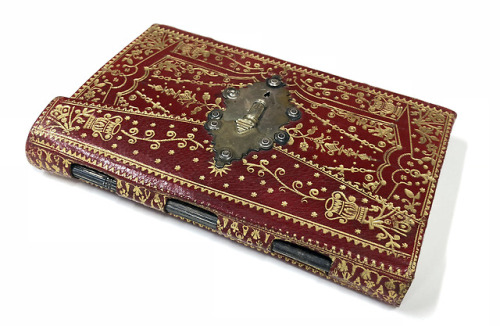

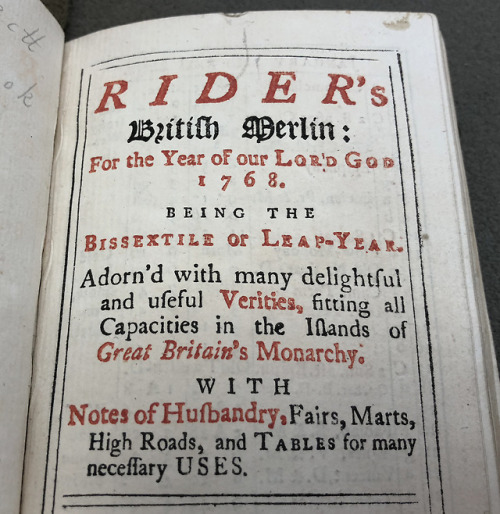

Unlocking a 250-Year-Old Almanac

Special Collections has recently acquired an intriguing copy of Rider’s British Merlin, an almanac published in London in 1768 — 250 years ago this year!

Rider’s almanac first appeared in 1656, “compiled for the benefit of his country” by one “Schardanus Rider,” believed to be an anagram of the name of physician and astrologer Richard Saunders (1613-1675). The almanac continued to be published for many years after his death.

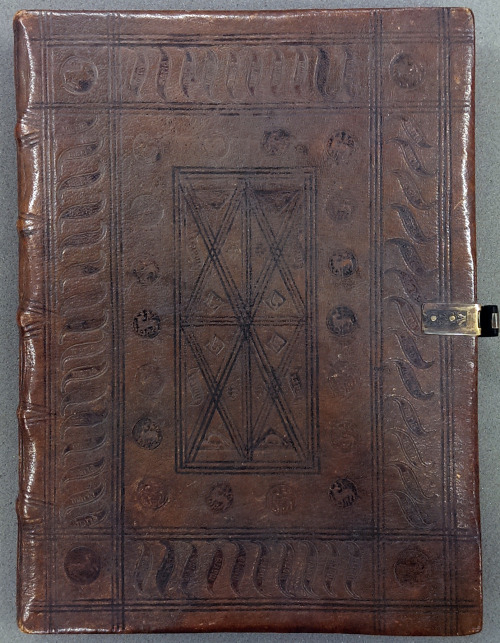

A number of special features make our copy uniquely interesting, such as its elaborate red morocco binding. Perhaps most fascinating is the metal lock, which is actually even more complex than it might appear at first glance. In spite of the provided key, it seems that the only way to truly open the lock is through a secret mechanism — by gently sliding one of the rivets connecting the lock to the cover, the inner latch shifts, and the flap can be opened.

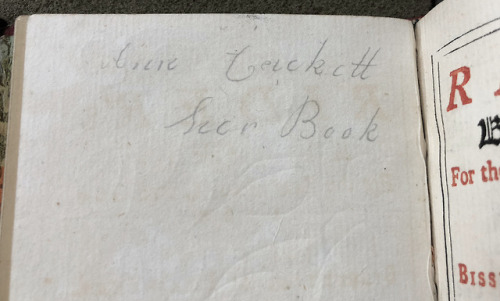

A convenient slot is incorporated into the flap to store a metal stylus, which is (happily) still present. This was used for taking notes on a pair of waxed sheets bound in at the front of the volume, which effectively acted as erasable writing tablets. In much the same way that the ancient Romans used wax-filled wooden frames for temporary note-taking, the pages in this almanac could be incised with the stylus and then erased at the appropriate time. An owner of this volume — perhaps Ann Cackett (?), who wrote her name on one of the flyleaves — has used the stylus many times, leaving incisions behind in the form of repeated circles and other rudimentary markings.

Inside each cover is a little fold-out pocket for the storage of important documents, though sadly they arrived at our library empty. These pockets are partially formed by the end-papers, which are made from beautiful multicolored Dutch gilt paper (actually originating in Germany). Our papers bear a portion of the name of their maker: “Johan Wilhelm.”

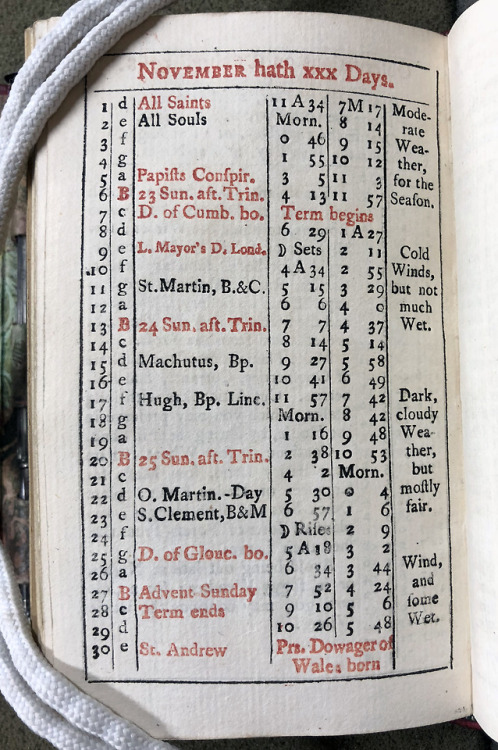

It’s easy to concentrate on this almanac’s bells and whistles, but it is also rewarding to look at its contents. It opens with a handsome calendar, printed in red and black, that incorporates religious, astronomical, meteorological, and agricultural observations. Other sections include a list of the year’s moveable feasts (holy days that occur on different days each year), a calendar of eclipses, a zodiac man (a diagram of the relationships of the planets to various parts of the human body), a table of the monarchs and the dates of their reigns, a description of the country’s major roads with the distances between towns, and an extensive list of the fairs regularly held in England and Wales.

Several pages are filled with the reckoning of the years since major events – 4061 since Noah’s Flood, 315 since “printing first used in England” (this is about 20 years earlier than the date generally accepted today), 188 since “a blazing star in May” was observed, and five since “a general peace.” Finally, there is a tipped-in sheet documenting “An account of the holydays” for 1768. (This is unrecorded in the English short title catalogue.)

We are excited to add this unique almanac to our collection, and look forward to welcoming you into our reading room to see it in person!

Post link

Remember, remember, the fifth of November!

Tonight is Guy Fawkes Night, an annual remembrance in the United Kingdom of the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605, in which Robert Catesby, Guy Fawkes, and other Catholic revolutionaries attempted to assassinate the Protestant King James I by blowing up the House of Lords during the opening of Parliament.

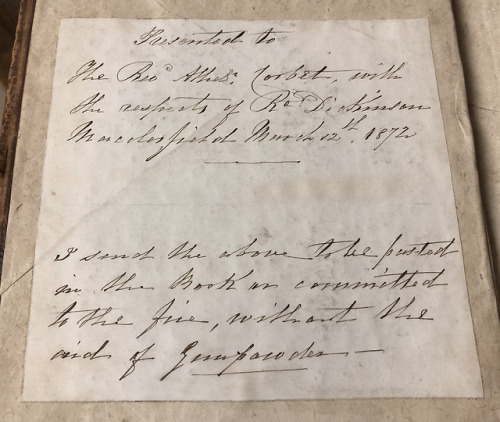

This1606 account of the trial of Henry Garnet, one of the Gunpowder Plot conspirators, bears an interesting and relevant presentation inscription pasted onto the front endpaper:

Presented to

the Revd. Athels[ta]n Corbet, with

the respects of Revd. Dickinson

Macclesfield March 12th, 1872I send the above to be pasted

in the book or committed

to the fire, without the

aid of gunpowder

Obviously (and thankfully, for provenance purposes), this presentation note was spared the fire!

~Andrew

Post link

If you’re in the habit of reading descriptions of old books—and why wouldn’t you be?—you’ve likely come across something described as bound in period style or in a sympathetic binding. This typically means the book was rebound relatively recently, but rebound in a style consistent with the time period of the book’s original publication.

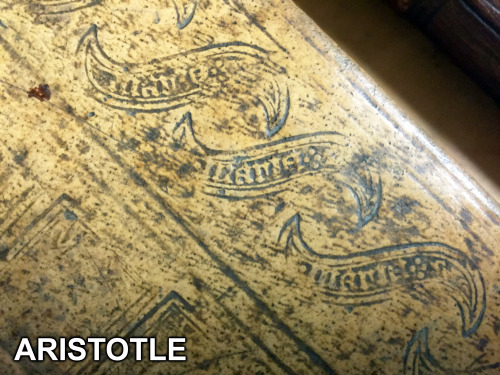

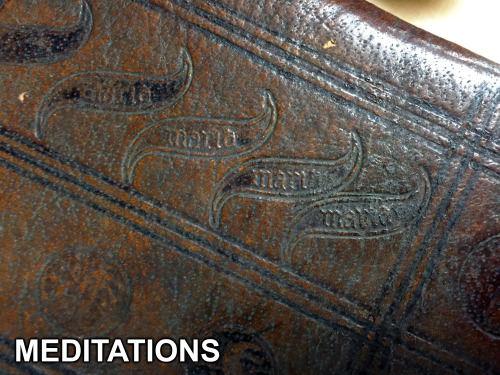

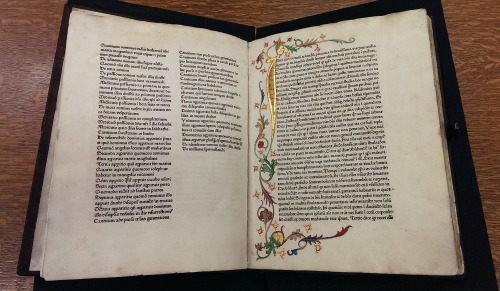

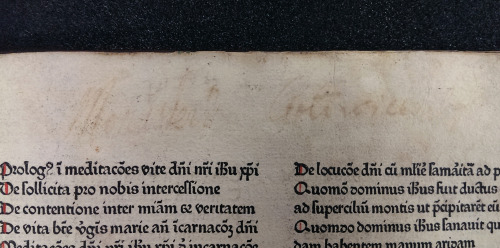

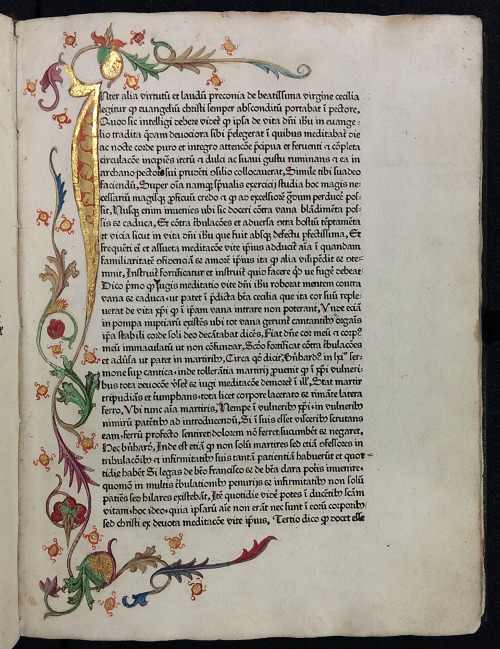

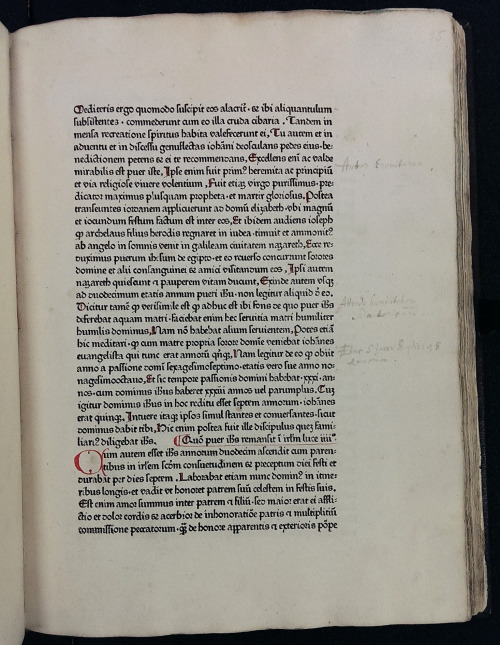

For example, our first edition of the Meditationes Vitae Christi (Meditations on the Life of Christ) was rebound in such a way. You can read more about this work—a recent acquistion—here.

And shortly after the Meditations arrived, we received the first printed Greek edition of Aristotle (it was a very good summer), which underscored just how well done this period-style binding was. Although the books were likely bound about 400 years apart—the Aristotle around 1500 and the Meditations around 1900—the styles are strikingly similar. The combination of borders built up from different tools, surrounding a central diaper pattern, was a familiar style when both were published. The Aristotle binding is almost certainly German, so it’s no surprise that the binding of the Meditations, which was printed in Augsburg in 1468, emulates a 15th-century German style.

Of all the similarities, what most caught our eyes was a particular tool used to decorate the boards. While obviously similar, small differences distinguish them. The Aristotle version, for example, has four tiny dots following Maria, while the Meditations version has no dots; a double border surrounds the Aristotle tool—thick on the outside, thin on the inside—while the Meditations tool has a single border; the Aristotle tool measures over 3 cm from end to end, while the Meditations tool measures just under 3 cm. The sheer volume of such tiny differences among tools is staggering. The Einbanddatenbank, a database of 15th- and 16th-century finishing tools used on German bindings, records more than 600 versions of the Mariatool.

How do we know the Meditations binding isn’t original? There are a number of clues, the general as-new appearance being a big one, but subtler evidence is there. The spine edges of wooden boards were commonly beveled in the late 15th century, but they aren’t here. Spines were seldom decorated at this time, yet the binder of the Meditations couldn’t help but to add some restrained decoration. Could these features be found on bindings from the late 15th century? Sure. But the accumulated weight of the evidence favors something done later in period style.

Make no mistake, the Meditations binder was good. Even the endpapers are period-appropriate leaves removed from an old book. This binding was absolutely the product of a skilled craftsperson with a thorough understanding of period styles—and perhaps the product of a binder with the skill and patience to make their own finishing tools.

~Pat

Post link

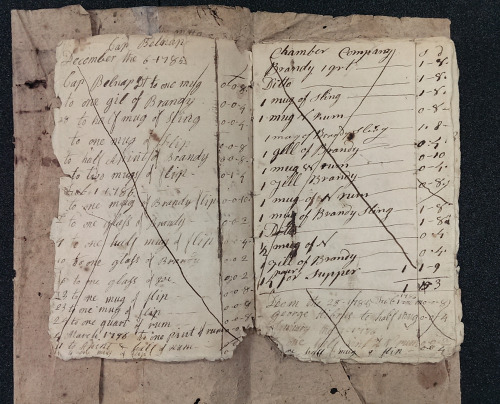

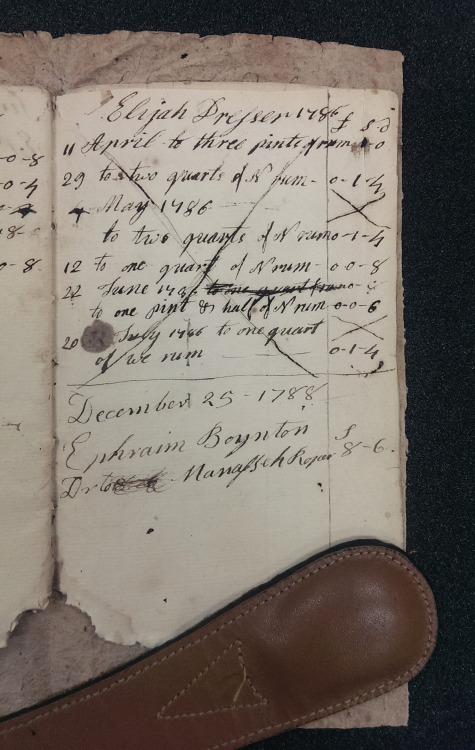

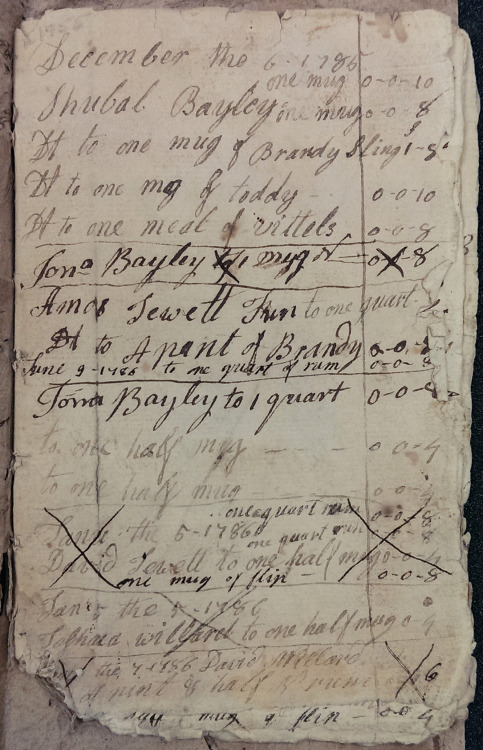

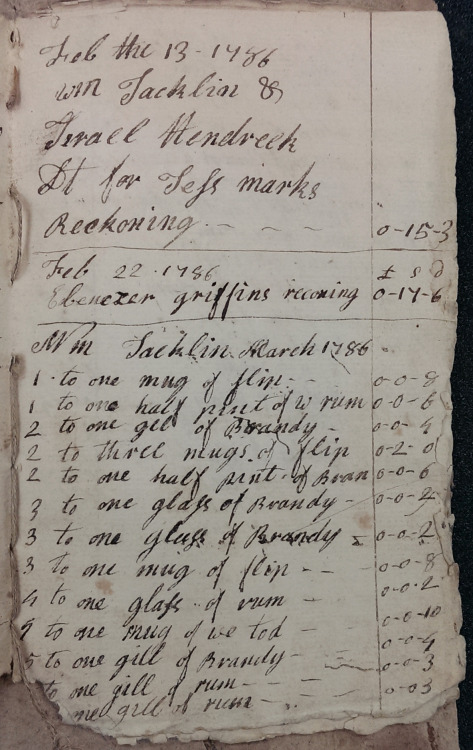

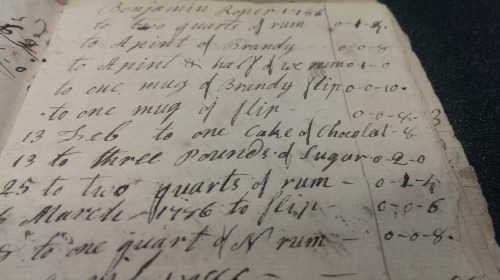

Picture the scene: A bustling New England tavern, December 1785. Two patrons sit at the bar, swapping war stories and discussing nascent U.S. political philosophy over mugs of… of what, exactly?

MSU Special Collections recently acquired an early American tavern keeper’s account book that can help answer that question—recording what American revolutionaries and their contemporaries were drinking (and eating) over two centuries ago.

Dating from December 1785 through 1788, this tavern keeper’s logbook tracks the sale of brandy, rum, flips, slings, toddies and other contemporary beverages, illustrating the drinking habits of 18th century New Englanders. There are some entries for meals, and for sales of salt, sugar, and other commodities (as well as “one cake of chocolate”), but unsurprisingly the most popular fare was liquid in nature.

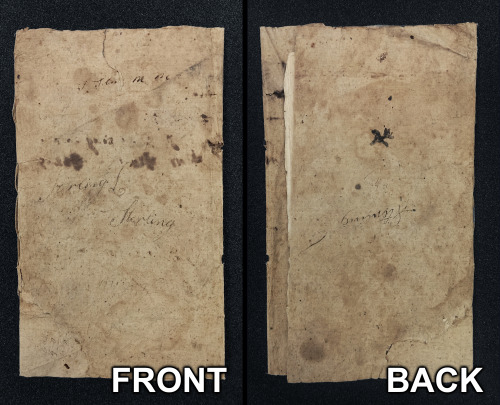

While the barkeep’s name remains anonymous, it is easy enough to trace the ledger to Sterling, Massachusetts—the town’s name is written several times across the tattered paper covers, and a number of personal names penned in the book can be found in Sterling’s early town records.

This manuscript account book is in amazingly good shape considering its age (231 years old) and heavy use, and it gives us a rare insight into the types of transactions that must have been commonplace at shops and taverns of the period. So join us in raising a mug of brandy flip (or a slice of chocolate cake, if you prefer) in honor of our recent acquisition!

http://catalog.lib.msu.edu/record=b11889851~S39a

~Andrew

Post link

One way to measure the popularity of a given text is to count the number of times it’s been published. For example, the immense popularity of The Imitation of Christ, which went through 78 editions in the 15th century, has been said to trail only the popularity of the bible itself as a devotional text. Compare these to 15 editions of Dante’s Divine Comedy in the 15th century and one can begin to appreciate just how popular Christian devotional literature once was. As it happens, MSU has one of just eight known copies of a rare 1495 editionofThe Imitation of Christ.

Not far behind the popularity of The Imitation of Christ, with at least 65 editions appearing in the 15th century, is the Meditations on the Life of Christ. MSU is very fortunate to have recently acquired the first printed edition of the Meditations—the very first of those many editions to appear in the 15th century (pictured above). Published in 1468, this edition has the distinction of being the first dated book printed in the city of Augsburg—and this at a time when fewer than a dozen cities in all of Europe had the technology to print books. This first appearance in print is a fine complement to our medieval manuscript of the text, and it also claims the honor of being one of the three oldest printed books to reside in Michigan.

On the front paste-down of our Meditations, afloat in a sea of booksellers’ annotations, is the bookplate of Hieronymus Baumgartner (1498-1565), a powerful advocate of the Protestant Reformation. Baumgartner enrolled at the University of Wittenberg in 1518, the very town in which just a year earlier Martin Luther allegedly nailed his Ninety-five Theses to a church door. In Wittenberg, Baumgartner befriended prominent reformers Philipp Melanchthon, Georg Major, and Joachim Camerarius, and he later helped found the Melanchthon Gymnasium in his hometown of Nuremberg in 1526. Baumgartner was an accomplished statesman, to be sure, but we’re particularly pleased because his bookplate, as far as we can tell, is the oldest bookplate in MSU’s collection.

~Pat

This Provenance Project guest post was written by Patrick Olson, Rare Books Librarian at Michigan State University Special Collections.

Post link

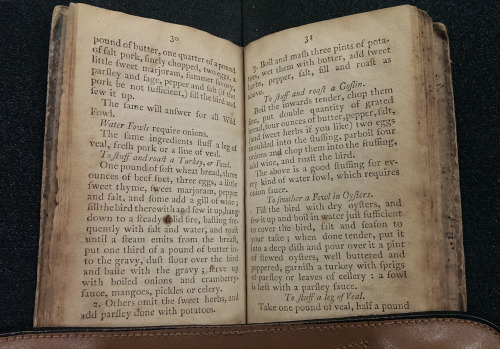

First published in 1796, American Cookery by Amelia Simmons is considered the first true American cookbook, with recipes for such indigenous foods as pumpkins, cranberries, and cornmeal. Cookbooks published here previously were English in origin with food and recipes written for English audiences.

American Cookery is the bedrock for all important cookbook collections and MSU Special Collections is fortunate to hold several early editions of the work, including the second printing of the first edition, published in 1798. We recently acquired another—the 1808 edition—published in Troy, New York.

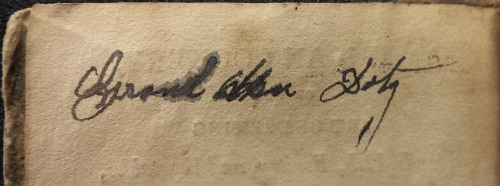

Any early edition of this important work is special, but this particular volume is extra special for its provenance. Boldly written on the inside of the front cover is the name “Ruth Doty,” who moved to Detroit from Troy, New York with her merchant husband Ellis Doty (a descendant of Edward Doty who came to America on the Mayflower). This volume was published three years after their marriage in 1805, so perhaps this was one of Ruth’s first cookbooks—and most likely journeyed with her over ten years as she and her growing family made their way west to Detroit by the early 1820s.

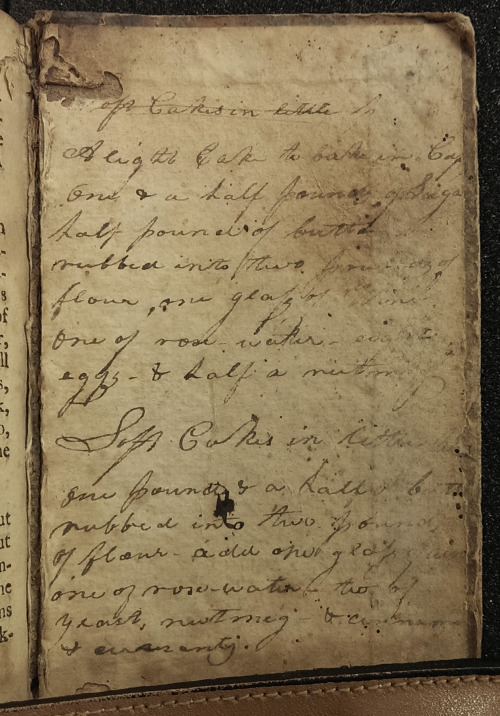

In addition to the inscription of Ruth Doty, there are other ownership clues in the book. On the inside of the back cover there are two manuscript recipes for cakes, in a different hand than Ruth’s. Most intriguing of all, on the verso of the title page is what looks like the name of another Doty… Can you make out what it says?

One can only speculate as to whether the cookbook stayed in the Doty family after Ruth’s death in 1866 at the age of 82, but its remarkably good shape despite its age, travels, and use clearly suggests that whoever owned the book realized its importance and historical value.

~Peter

Post link

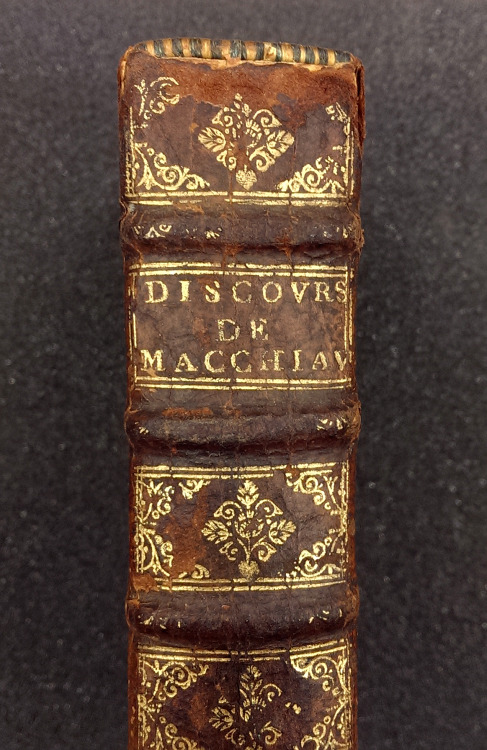

In preparing for the purchase of another title by the Italian Renaissance philosopher, Niccolo Machiavelli, I found this sixteenth century rebuttal of the principles of Machiavelli by the French jurist Gentillet.

In his book, Discours sur les moyens de bien gouverner, Gentillet analyzes the character of a ruler, rights of parliament, and capacity of councilors among other traits of good statecraft. It is landmark book and quite uncommon, but what struck my eye immediately was the term “CONTREMACH:” boldly written on the top of the text block. At first glance I thought an owner of the book used the term for shelving purposes, but why write such an aid on the top of the text block where it is not readily seen? And more importantly, what does “contremach” mean?

After showing this to Andrew Lundeen, founder of the MSU Provenance Project, he quickly determined that the term “contremach” is really an abbreviated reference to the title (or shorthand name) of the work and was likely used for shelving purposes. That is to say, CONTREMACH:orCONTRE MACH: stands for “Contre [Against] Mach[iavelli].”

~Peter

This Provenance Project guest post was written by Peter Berg, Head of Special Collections and Associate Director for Special Collections & Preservation at Michigan State University.

——————–

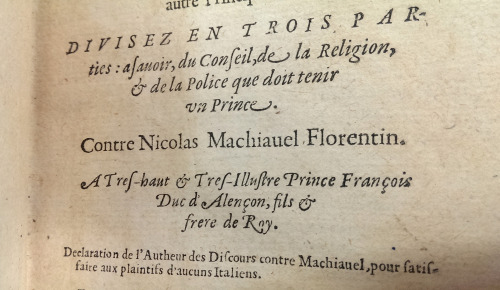

Andrew’s note: This fascinating little volume illustrates a couple of interesting facts about working with old books. Firstly, we should never assume that a work only went by one title, or even that the full printed title of a book was the preferred nomenclature. Formal titles were often absurdly long-winded, and so abbreviated titles or referential names were frequently used in their place. This particular copy of Gentillet’s work, for example, bears three different names on the item itself: “Discours sur les moyens [etc.]…” on the printed title page, “Discours de Macchiav[elli]” on the spine, and “Contremach” or “Contre Mach” on the top edge of the text block (the abbreviation is taken from a portion of the work’s subtitle: “ContreNicolasMachiauel Florentin”).

This confusion about how to “properly” refer to the work can be seen in the various names of reprints and later editions as well. Here at MSU we have several versions of this work cataloged under different titles:

Discovrs svr les moyens [etc.]… — With the name copied directly from the title page of this 1579 printing (inc. the archaic use of “V”s for “U”s)

Discours contre Machiavel — The title of this 1974 updated edition

And finally, Anti-Machiavel — A 1968 printing that uses a historically common shorthand title for the work, one very similar to our CONTREMACH edgemarkSecondly, the placement of our CONTREMACH title indicates that this book may not have always been shelved in the way most modern readers and library-goers are familiar with—upright with its spine facing outward. The use of edge-marks such as this, as well as historical depictions of book collections in art, show that books were often stacked on top of one another with the edges of their text blocks visible.

And just because it’s relevant, I’m going to piggyback off this post to share a recent acquisition for MSU Special Collections: A 17th century edition of Machiavelli, backdated to circumvent Church censorship. From the bookseller’s description:

“As Machiavelli’s works were placed on the Pope’s Index librorum prohibitorum in 1559, later issuing of his works use a false date as an imprint (as in 1550, the original date of publication) to avoid censorship.”

Pretty cool stuff!

http://catalog.lib.msu.edu/record=b11870408~S23a

~Andrew

Post link

In preparing for the purchase of another title by the Italian Renaissance philosopher, Niccolo Machiavelli, I found this sixteenth century rebuttal of the principles of Machiavelli by the French jurist Gentillet.

In his book, Discours sur les moyens de bien gouverner, Gentillet analyzes the character of a ruler, rights of parliament, and capacity of councilors among other traits of good statecraft. It is landmark book and quite uncommon, but what struck my eye immediately was the term “CONTREMACH:” boldly written on the top of the text block. At first glance I thought an owner of the book used the term for shelving purposes, but why write such an aid on the top of the text block where it is not readily seen? And more importantly, what does “contremach” mean?

After showing this to Andrew Lundeen, founder of the MSU Provenance Project, he quickly determined that the term “contremach” is really an abbreviated reference to the title (or shorthand name) of the work and was likely used for shelving purposes. That is to say, CONTREMACH:orCONTRE MACH: stands for “Contre [Against] Mach[iavelli].”

~Peter

This Provenance Project guest post was written by Peter Berg, Head of Special Collections and Associate Director for Special Collections & Preservation at Michigan State University.

——————–

Andrew’s note: This fascinating little volume illustrates a couple of interesting facts about working with old books. Firstly, we should never assume that a work only went by one title, or even that the full printed title of a book was the preferred nomenclature. Formal titles were often absurdly long-winded, and so abbreviated titles or referential names were frequently used in their place. This particular copy of Gentillet’s work, for example, bears three different names on the item itself: “Discours sur les moyens [etc.]…” on the printed title page, “Discours de Macchiav[elli]” on the spine, and “Contremach” or “Contre Mach” on the top edge of the text block (the abbreviation is taken from a portion of the work’s subtitle: “ContreNicolasMachiauel Florentin”).

This confusion about how to “properly” refer to the work can be seen in the various names of reprints and later editions as well. Here at MSU we have several versions of this work cataloged under different titles:

Discovrs svr les moyens [etc.]… — With the name copied directly from the title page of this 1579 printing (inc. the archaic use of “V”s for “U”s)

Discours contre Machiavel — The title of this 1974 updated edition

And finally, Anti-Machiavel — A 1968 printing that uses a historically common shorthand title for the work, one very similar to our CONTREMACH edgemark

Secondly, the placement of our CONTREMACH title indicates that this book may not have always been shelved in the way most modern readers and library-goers are familiar with—upright with its spine facing outward. The use of edge-marks such as this, as well as historical depictions of book collections in art, show that books were often stacked on top of one another with the edges of their text blocks visible.

Post link

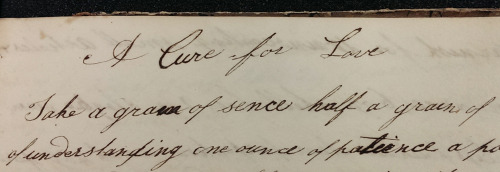

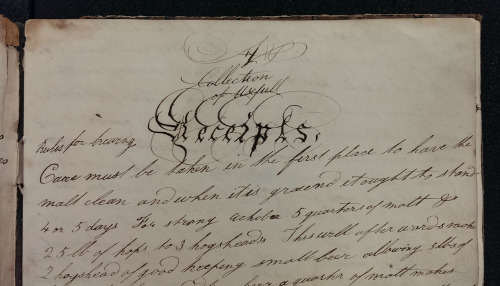

Valentine’s Day is nearly upon us! And while it can be a time of joy for many, for some it is more bittersweet, recalling memories of past heartache. If you fall into the latter camp this year, don’t fret—we uncovered the remedy you might need in an old manuscript recipe book.

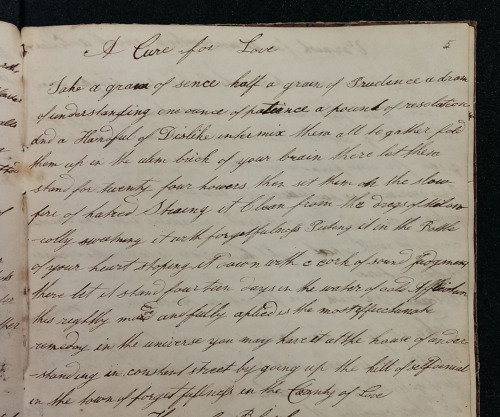

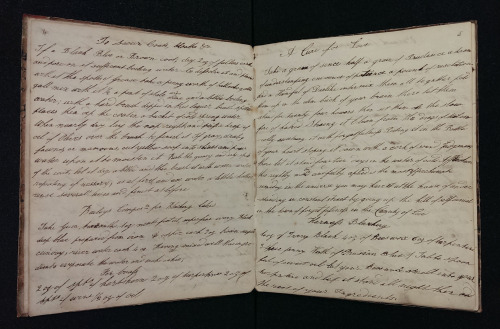

“A Cure for Love” was penned on one page of this 19th century Collection of Useful Receipts, a handwritten book containing recipes for food as well as home remedies for various diseases and conditions. And while some of the directions might be a tad difficult to follow, we’ve been assured that this cure is the best around:

Take a gram of sence [sense] half a gram of Prudence a dram

of understanding one ounce of patience a pound of resolution

and a Handful of Dislike intermix them all together fold

them up in the [???] brick of your brain there let them

stand for twenty four howers [hours] then set them on the slow

fire of hatred Straing [?] it clean from the dregs of Melon-

-colly [melancholy] sweetning it with forgetfulness putting it in the Bottle

of your heart stop[p]ing it down with a cork of sound judgment

there let it stand fourteen days in the water of cold Affliction

this rightly made and fully ap[p]lied is the most effectunate [effectual?]

remedy in the universe you may have it at the house of under-

-standing in constant street by going up the hill of self denial

In the town of forgetfullness in the County of Love

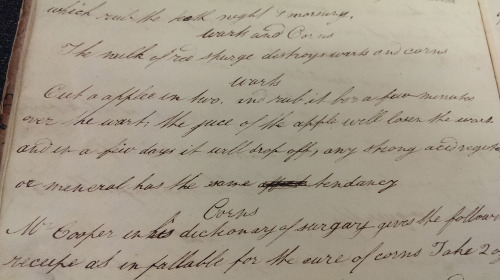

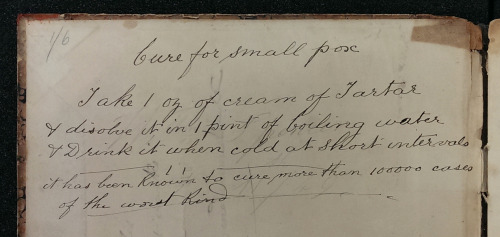

This cure for love appears alongside many other medical remedies, including ointments for “warts and corns” and a supposed cure for smallpox. Whoever created this manuscript apparently considered love a very serious condition indeed.

http://catalog.lib.msu.edu/record=b10316781~S39a

~Andrew

Post link

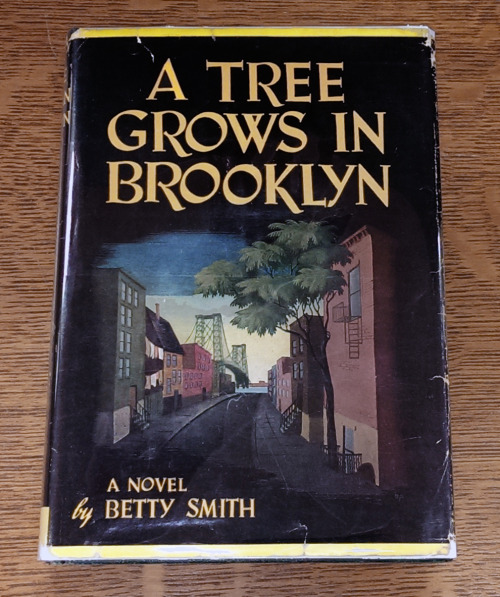

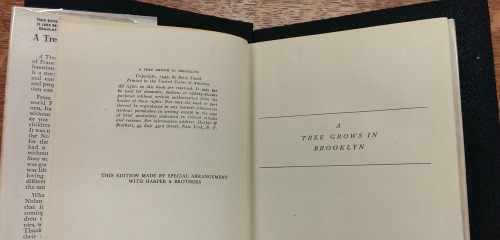

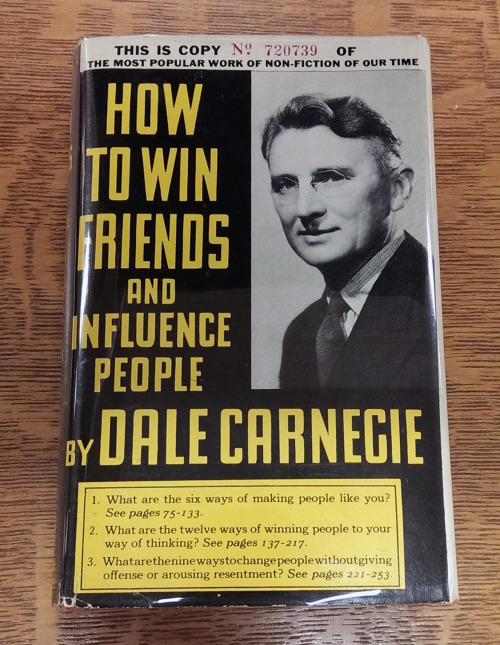

As part of our initiative to collect the first or earliest possible edition of books cited in the Library of Congress “Books That Shaped America” list, we recently acquired two books on the list that are worthy of recognition in our Provenance Project.

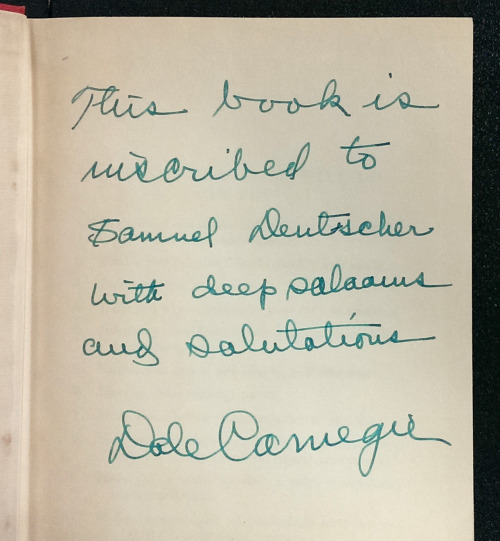

One acquisition is a first edition of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, which features the autograph of the author, Betty Smith, while the second book is a later printing of a first edition of How to Win Friends and Influence People. In it, the author Dale Carnegie provides a lengthy inscription on the front endpaper:

This book is inscribed to Samuel Deutscher with deep salaams and salutations

Dale Carnegie

The book—which is considered the grand-daddy of all self-help books—sold over 15 million copies, and while we’re confident that our readers are already enthusiastic book lovers, perhaps we’ll study Carnegie’s principles to make our audience feel even more “important and appreciated.”

~Peter

This Provenance Project guest post was written by Peter Berg, Head of Special Collections and Associate Director for Special Collections & Preservation at Michigan State University. Dr. Berg received his undergraduate degree in History from MSU in 1969, his Library Science degree from the University of Michigan in 1975, and his doctorate in History from MSU in 1994.

Post link

We’ve probably all done this before. While out and about, perhaps while traveling or shopping, we lay a scrap of paper inside a book. Maybe it’s a receipt for the book’s purchase, or perhaps it’s a plane ticket. Whatever it is, we probably don’t give it much thought at the time. But decades later, or even centuries, those scraps of paper can prove more fascinating than the host book itself.

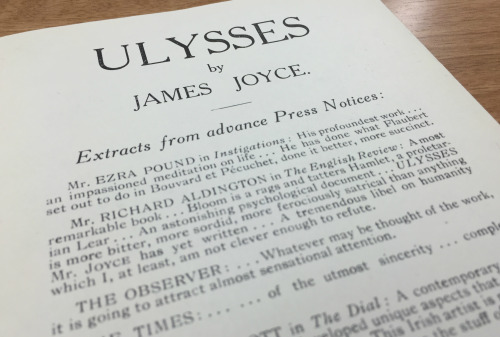

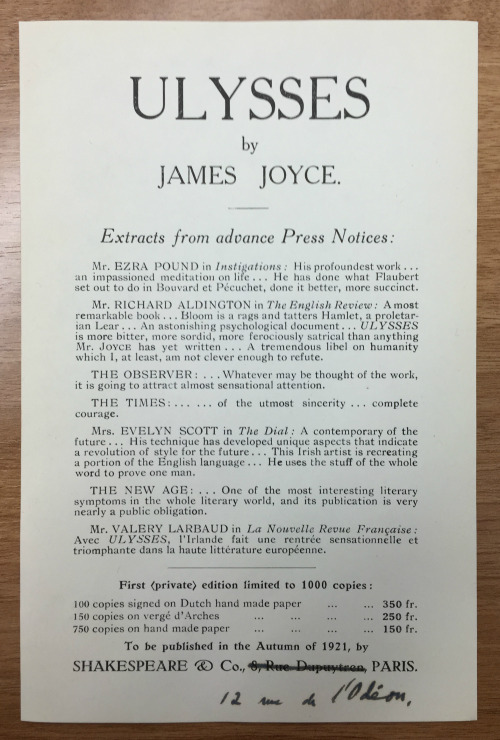

Not to discount Robert McAlmon’s first book, Explorations, but what we found laid inside our 1921 first edition was far more interesting: an early advertisement for Ulysses (as it happens, McAlmon edited Joyce’s Ulyssesmanuscript).

Early press for Ulysses more commonly manifests as a four-page prospectus that included a detachable order form. There were two versions of this that indicated Ulysses would be published in “Autumn of 1921”—just like our single-leaf advertisement (the book was finally published in 1922). One of these prospectuses bore the earlier address of Shakespeare & Co., 8 rue Dupuytren. The second of these prospectuses bore the new address, 12 rue de l’Odéon. Our advertisement here has the earlier address, though corrected by hand (someone please tell us if it’s Sylvia Beach’s hand!) to reflect the new rue de l’Odéon address. So with a bit of sleuthing and some help from The Poetry Collection at the University at Buffalo, we can confidently suggest that this rare Ulysses ad was printed about the same time as the first prospectus.

As you might expect, printed ephemera aren’t known for their survival skills. WorldCat locates two other copies of this particular ad, one each at Yale and Cornell. Surely there are others out there, safely filed away in archival collections—or perhaps just languishing inside an old book, a forgotten memento of a visit to a Paris bookstore in 1921.

~Patrick

This Provenance Project guest post was written by Patrick Olson, Rare Books Librarian at MSU Special Collections. Patrick joined Michigan State University in 2014, having previously held special collections positions at the University of Iowa, MIT, and the University of Illinois, where he also earned his MLIS. Prior to becoming a librarian, he spent four years working in the rare book trade.

Post link

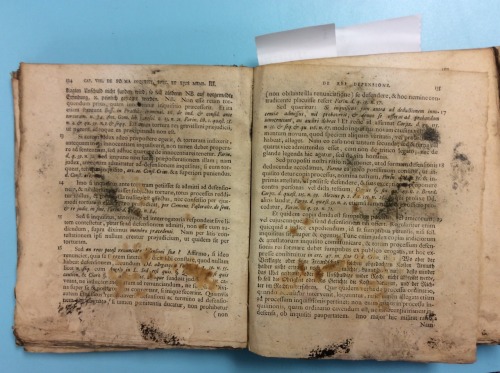

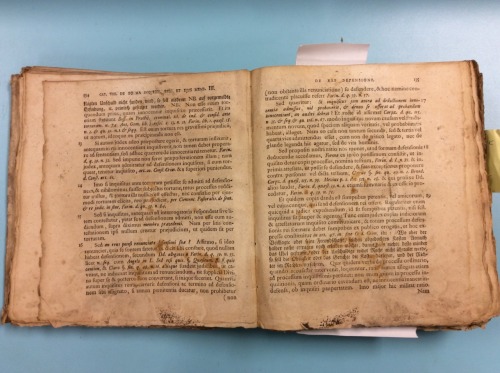

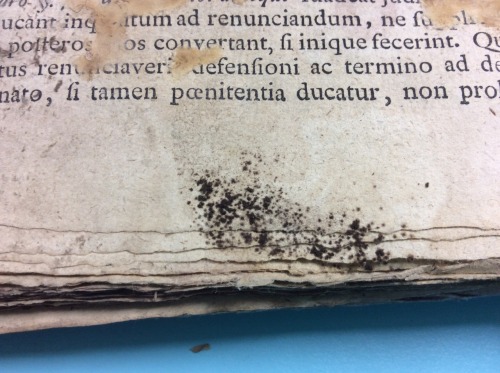

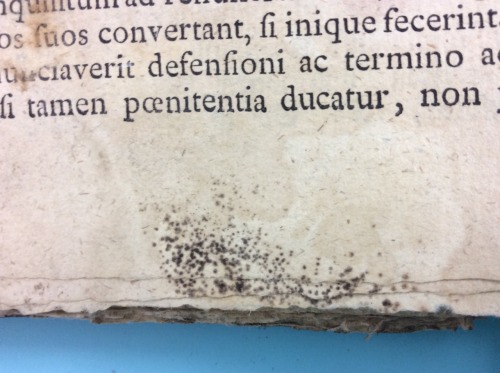

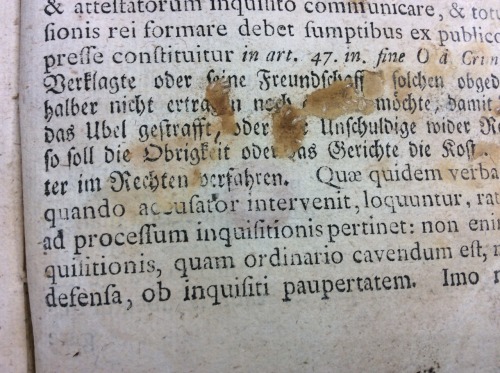

This poor book was full of mold, dirt, and accretions. (I urge you to click on the first image so that you can see a larger version). The mold was inactive when it came down to the lab, but the dark, black, fuzzy stuff still made me shudder.

I vacuumed the entire book - page by page - in the fume hood, using a vacuum with a HEPA filter, and wearing personal protective clothing. It took about 3 hours to vacuum the entire book.

Even inactive mold can produce allergic symptoms in sensitive individuals, and we wouldn’t want our patrons to become sick while using our collections! Although the mold spores have been removed, some staining remains. Additional conservation is needed to make this book usable, since the sewing is broken, the pages are loose, and the binding is badly distorted. Just another item for my “to do” list!

-Bexx

Yuck! These are the kinds of copy-specific features we don’t want to preserve for posterity. The staining, at least, tells a story—but the presence of the mold itself (active or inactive) is obviously a serious health risk.

For more on moldy books and what to do with them, check out these other fantastic posts from our Library’s Wallace Conservation Lab Tumblr:

Mold, certain adhesives, and some pigments fluoresce under UV light

Mold from a July 4th, 2015 water leak (extra disgusting)

Purple paper staining the result of extensive mold damage

Vacuuming moldy books in the conservation lab (gif)

A big thank you to all the conservators out there for the work you do—behind the scenes—keeping patrons and staff safe and ensuring our library books are usable for generations to come!

~Andrew

Post link