#provenance

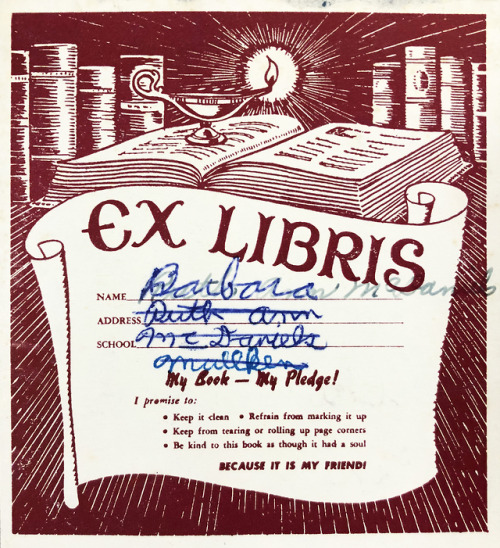

Over the years, many primary and secondary schools have employed bookplates to admonish students against marking up their textbooks. These three examples all come from 1940s American school books, but each one delivers its message in a very different way!

Some school bookplates, such as this eye-catching red one pasted into a 1942 third-grade grammar book, are touchingly poetic, requiring that its owner promise to:

Keep it clean; Refrain from marking it up; Keep from tearing or rolling up page corners; Be kind to this book as though it has a soul

Because it is my friend!

Other examples seem a bit more sterile, by comparison. The language used in this 1947 French textbook, for example, matches the plain, utilitarian design of the bookplate:

Please do not write in this book. Remember that other students must use it later. Please keep it as neat and unsoiled as you can. Your cooperation in this matter will be appreciated.

Our final bookplate, from a 1946 English reader, is decidedly more… civic-minded. Issued and owned by the State of Arizona, this label outlines what it calls the “Good Citizenship Code For Pupils Using State Textbooks”, a set of rules that includes such pledges as:

I will respect and take care of the property of the State.

I will keep my books clean outside and inside.

I will not spoil their pages with finger prints.

I will guard my books as a trust from the State.

I will keep my books fit for those to use who come after me as I expect those who come before me to keep their books fit for me to use.

Of course, as we have seen over andover andover again, schoolchildren were generally not afraid to mark up their textbooks. We’ll leave it to our followers to decide which books (in the words of that first bookplate) have more soul: the clean, unmarked copies or the used and soiled ones.

Post link

Today, April 23, is Shakespeare’s birthday! Maybe. Supposedly. It was certainly the date of his death in 1616, but it also commonly celebrated as the date of his birth, some 52 years earlier in 1564.

Several editions of the Bard’s works were printed before his death, but the most complete and most famous collections of his plays are the large folio editions, produced posthumously.

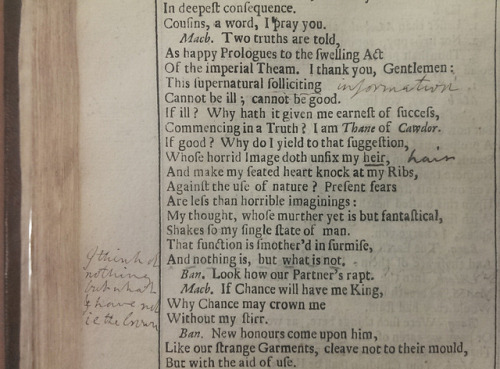

While these beautiful and rare 17th century Shakespeare folios are a significant improvement over the earlier “bad” quarto versions, they are far from perfect copies of Shakespeare’s works.

In the case of own Fourth Folio, it appears as though a previous owner sought to correct some of the numerous typographical errors throughout the volume. Our dutiful annotator has also added several marginal notes commenting on various passages in the text.

Some of these typos really change the meaning of the text in humorous ways:

If good? Why do I yield to that suggestion,

Whose horrid image doth unfix my heir [hair]

- Macbeth, Act I, Scene 3

What if it tempt you toward the Floud, my Lord?

Or to the dreadful Sonnet of the Cliff [summit]

- Hamlet, Act I, Scene 4

My fault is past. But oh, what form of Prayer

Can serve my turn? Forgive me my foul Mother [murther/murder]

- Hamlet, Act III, Scene 3

All those bored scholars with nothing better to do than overanalyze Shakespeare’s works looking for hidden messages should have a field day with some of these passages.

Post link

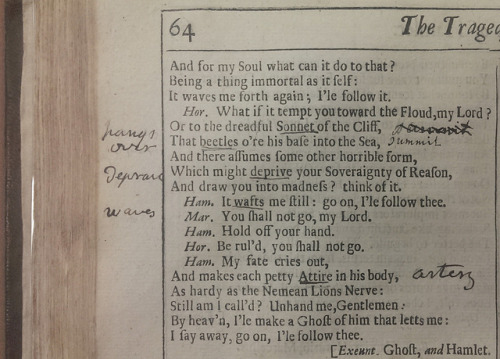

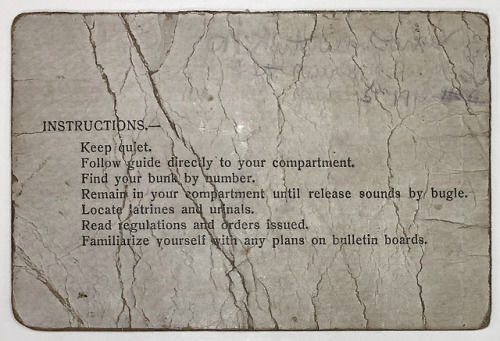

More highlights from our file of “Things Found in Library Books!”

One interesting piece from this collection of orphaned ephemera is a troop billet card for the U.S.S. Leviathan, a massive German-built steamship seized by the United States in 1917 and used as a troop transport during World War I. While we can’t quite make out the name penciled on the back of the card, we can (just barely) read the annotation below, which allows us to date this particular voyage:

Left New York Harbor

June 15th 1918

Can anyone read the name of the soldier in bunk #895? While we can’t say for sure if the former owner of this card made it home from the War, the fact that the card survived gives us some hope.

During its tenure as a military transport, the Leviathan ferried over 119,000 American troops between the United States and Europe. After the War ended, the ship was refitted again to serve as a passenger liner for the United States Lines, and continued to sail across the Atlantic for another 20 years.

Post link

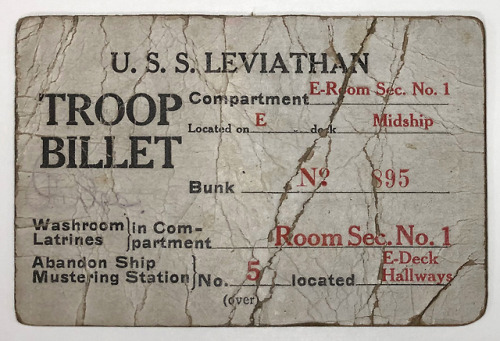

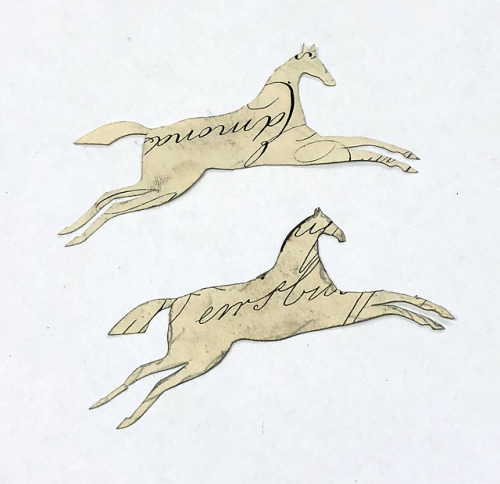

There’s a lot more to studying provenance than deciphering arcane inscriptions and other marks of ownership. Sometimes previous owners will leave other traces of themselves behind, like these loose items we’ve found stuck between the pages of many of our old books.

These pieces of ephemera, or transitory materials originally meant to be discarded after a few uses, have survived against all odds — in some cases for over 100 years — as forgotten bookmarks, safely tucked away and waiting for our librarians or catalogers to stumble across them.

Unfortunately, these particular ephemera are orphaned materials, their original sources unknown or undocumented. Where they might have come from, what books they were originally found in — these remain mysteries that we will probably never solve. But while their usefulness as pieces of provenance evidence is likely nonexistent, these fragile, rarely-preserved fragments of another time and place are still interesting in their own right.

Post link

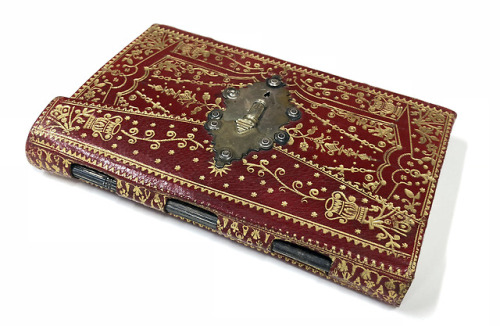

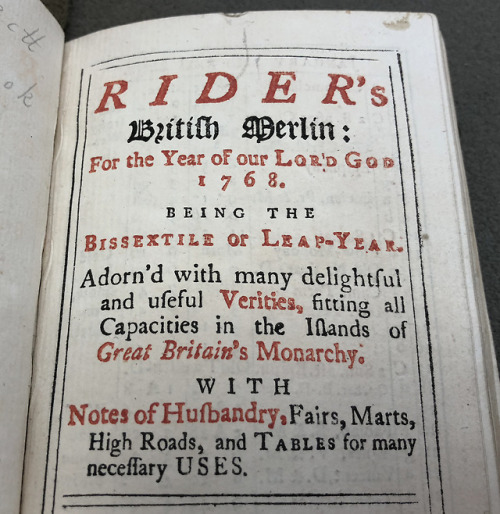

Unlocking a 250-Year-Old Almanac

Special Collections has recently acquired an intriguing copy of Rider’s British Merlin, an almanac published in London in 1768 — 250 years ago this year!

Rider’s almanac first appeared in 1656, “compiled for the benefit of his country” by one “Schardanus Rider,” believed to be an anagram of the name of physician and astrologer Richard Saunders (1613-1675). The almanac continued to be published for many years after his death.

A number of special features make our copy uniquely interesting, such as its elaborate red morocco binding. Perhaps most fascinating is the metal lock, which is actually even more complex than it might appear at first glance. In spite of the provided key, it seems that the only way to truly open the lock is through a secret mechanism — by gently sliding one of the rivets connecting the lock to the cover, the inner latch shifts, and the flap can be opened.

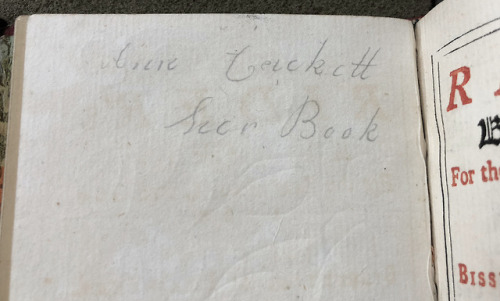

A convenient slot is incorporated into the flap to store a metal stylus, which is (happily) still present. This was used for taking notes on a pair of waxed sheets bound in at the front of the volume, which effectively acted as erasable writing tablets. In much the same way that the ancient Romans used wax-filled wooden frames for temporary note-taking, the pages in this almanac could be incised with the stylus and then erased at the appropriate time. An owner of this volume — perhaps Ann Cackett (?), who wrote her name on one of the flyleaves — has used the stylus many times, leaving incisions behind in the form of repeated circles and other rudimentary markings.

Inside each cover is a little fold-out pocket for the storage of important documents, though sadly they arrived at our library empty. These pockets are partially formed by the end-papers, which are made from beautiful multicolored Dutch gilt paper (actually originating in Germany). Our papers bear a portion of the name of their maker: “Johan Wilhelm.”

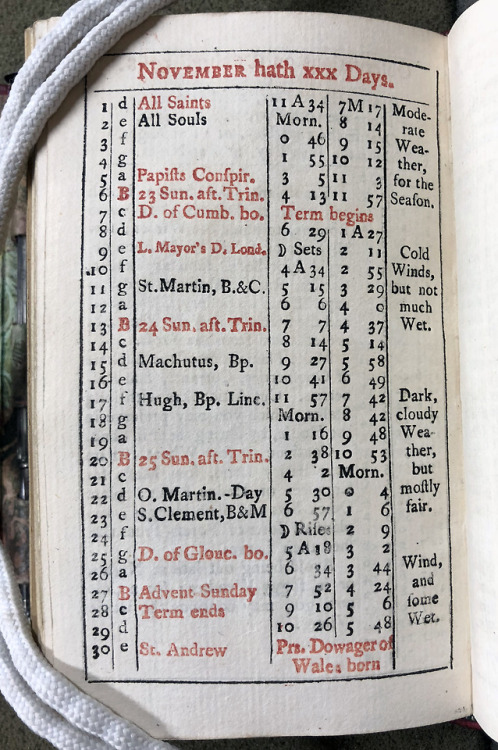

It’s easy to concentrate on this almanac’s bells and whistles, but it is also rewarding to look at its contents. It opens with a handsome calendar, printed in red and black, that incorporates religious, astronomical, meteorological, and agricultural observations. Other sections include a list of the year’s moveable feasts (holy days that occur on different days each year), a calendar of eclipses, a zodiac man (a diagram of the relationships of the planets to various parts of the human body), a table of the monarchs and the dates of their reigns, a description of the country’s major roads with the distances between towns, and an extensive list of the fairs regularly held in England and Wales.

Several pages are filled with the reckoning of the years since major events – 4061 since Noah’s Flood, 315 since “printing first used in England” (this is about 20 years earlier than the date generally accepted today), 188 since “a blazing star in May” was observed, and five since “a general peace.” Finally, there is a tipped-in sheet documenting “An account of the holydays” for 1768. (This is unrecorded in the English short title catalogue.)

We are excited to add this unique almanac to our collection, and look forward to welcoming you into our reading room to see it in person!

Provenance addendum: This beautiful little almanac also bears an original two-penny duty stamp in the lower corner of its title page. This was mandated by the Stamp Act of 1712, which assessed duties on all sorts of printed matter (a version of this act was instituted in the colonies in 1765, and the reaction against it helped to spur on the new cause of American independence).

Post link

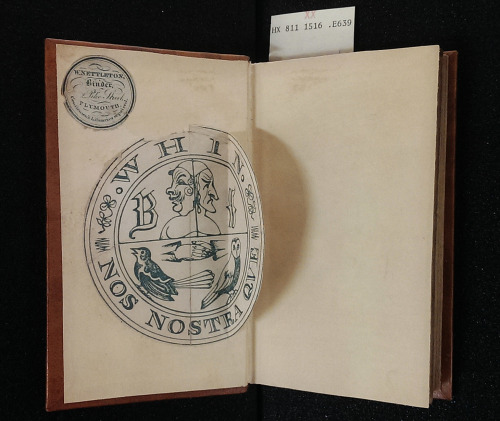

This armorial crest is pretty neat. I hope our super awesome special collections cataloger can use it to identify the the book’s original owner. #specialcollections #provenance #cataloging #bookstagram (at MSU Libraries)

The arms are those of the Amelot family, and likely a high-ranking member of the French nobility, given the helm. Hopefully the book has enough other context clues to narrow down which Amelot it might have been!

Post link

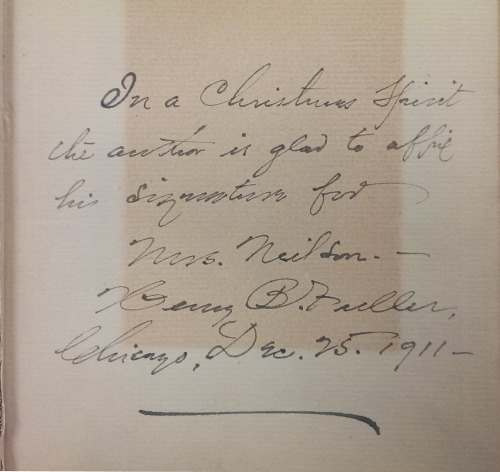

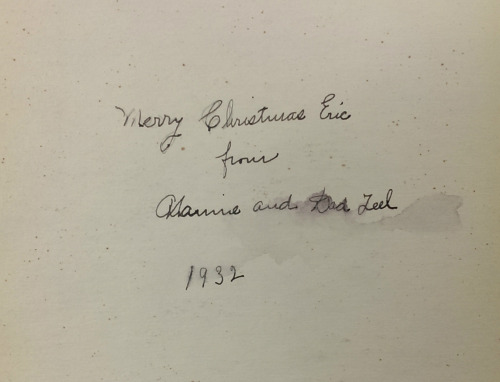

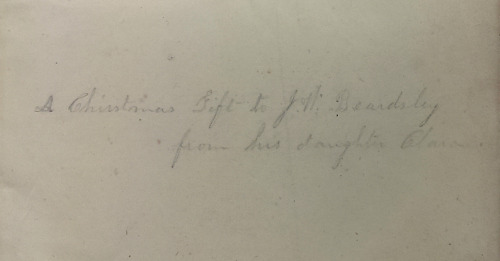

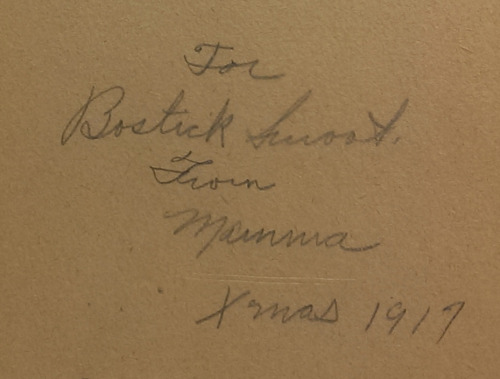

One of the most common kinds of presentation notes we find, especially in books printed within the last 200 years or so, is the Christmas gift inscription. Whether from friends, family, or the authors themselves, these notes show that books have been popular gifts for generations.

The inscriptions shown here appear in the following works (in the order in which they appear above):

http://catalog.lib.msu.edu/record=b1967953~S39a

http://catalog.lib.msu.edu/record=b1959977~S39a

http://catalog.lib.msu.edu/record=b2963814~S39a

http://catalog.lib.msu.edu/record=b10009534~S39a

http://catalog.lib.msu.edu/record=b9074626~S39a

http://catalog.lib.msu.edu/record=b2959512~S39a

http://catalog.lib.msu.edu/record=b1958508~S39a

http://catalog.lib.msu.edu/record=b1588168~S39a

http://catalog.lib.msu.edu/record=b1570932~S39a

We hope you’ll continue the tradition and give away lots of books this holiday season!

~Andrew

Post link

This interesting modern bookplate is just a liiiiittle too big for its book. The right third of the plate is not pasted down, and instead has been folded over so that the book can be closed.

Maybe this owner should have invested in smaller bookplates, but this is a pretty ingenious solution. Has anyone seen a similar example?

http://catalog.lib.msu.edu/record=b1544257~S39a

~Andrew

Post link

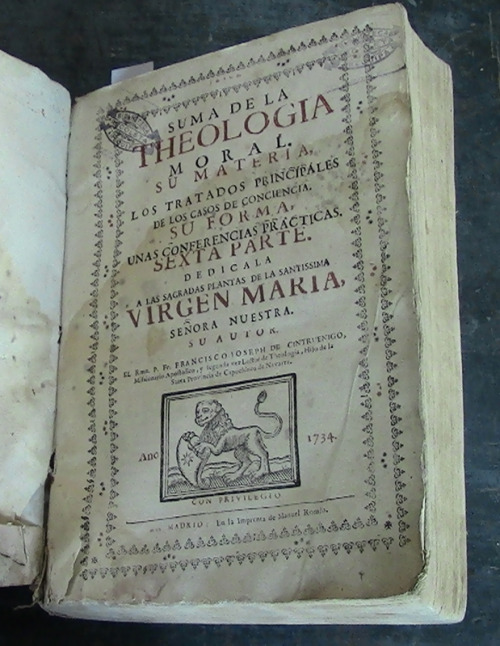

The Recoleta has at least sixteen volumes from various editions of the Suma de la theologia moral, by Corella and Cintruenigo (see more volumes here). This particular copy of part six of the 1734 edition has some interesting interventions.

First, the title page shows evidence of poor masking and registration when printing the red and black. Notice the doubled tilde of “Señora” under “Virgen Maria.”

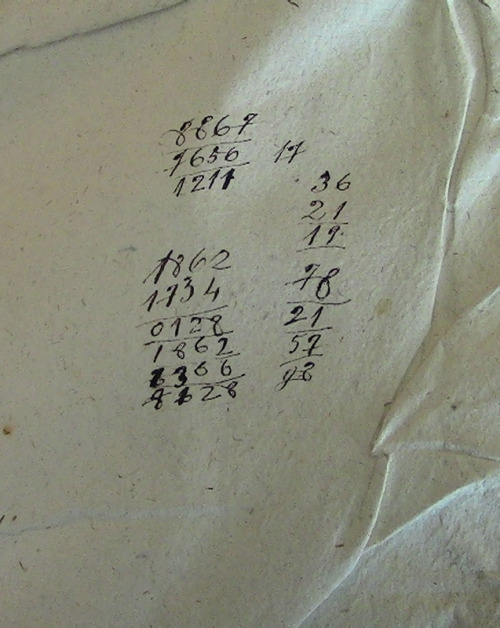

Second, there are some math problems on the pastedown inside the back cover. I recognize the 1734 from the date of publication. Was this a user from 1862 trying to work out how many years it had been since the book was published?

Third, we have an undated note in Spanish that was used as a bookmark. We haven not yet tried to translate it, so any attempts would be welcome.

Fourth, the marca de fuego.

-John

Post link

Ubdugs and Bunderloghs

For almost completely non-polar reasons, I’ve been reading Kipling’s original Jungle Book. It’s interesting, both from a historical perspective and the perspective of an ex-Disney animator* but there was also an intriguing linguistic thing that came right back to Cape Evans.

When the Afterguard (officers and scientists) moved from the Terra Nova’s wardroom to the ‘wardroom’ of the Cape Evans hut, they split into two factions, depending which side of the hut they slept on. Those in the 'Tenements’ (Birdie, Cherry, Oates, Atch, and Meares) were the 'Bunderloghs.’ At least, that’s how I’ve seen in spelt in secondary histories; it comes from an article in the South Polar Times in which a rabbit (Crean’s?) makes scientific observations on the inhabitants of the hut and deliberately obfuscates names with cod-phonetic spellings. In his discussion of them, he compares them to 'the Indian Banderlogs’, which is similarly nonsense …

… except that the monkey people in The Jungle Book, notorious for their anarchy, short attention span, and disruptive behaviour, are named the Bandar-log. Now you know.

On the other side of the hut was the 'Opium Den’, whose denizens were known as the 'Ubdugs.’ Having discovered that there was a provenance for Bunderlogh, I was curious where Ubdug might have come from. Google has only brought me one source, but it’s possible: a Carroll-esque poem by an American children’s writer named Charles E. Carryl, which was published in 1885, and contains the verse

All nautical pride we cast aside

And we ran the vessel asho-o-ore

On the Gulliby Isles where the poopoo smiles

And the rubbily ubdugs roar

Composed of sand was that favored land

And trimmed with cinnamon straws

And pink and blue was the pleasing hue

Of the ticke-toe teaser’s claws

This was titled 'A Capital Ship’ or 'The Walloping Window-Blind’; curiously, the poem was also published under the title 'A Nautical Ballad’ but that version does not contain any reference to Ubdugs. Would they have known this poem? Most of them were children in the 1880s and '90s; it might have crossed their paths. Where else would they have got the word from? Could it have been suggested by 'rubbily,’ given 2/3 of the Ubdugs were geologists? We may never know. But it’s fun.

*The lore has it that the director told the crew not to read the book if they hadn’t already. Boy, he wasn’t kidding: the Disney version is nothing like the original.

Use the time to prove yourself right.

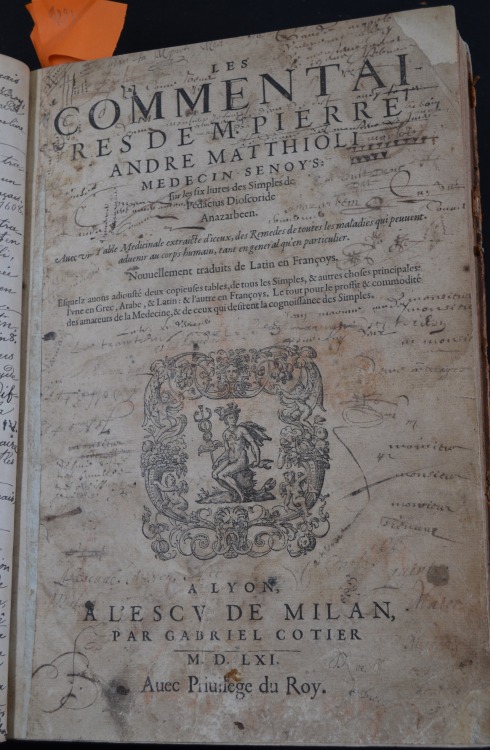

Happy Title Page Tuesday! This fantastic 1561 Latin edition of Mattioli’s herbal is a part of the Croughan donation, which we wrote about here. As you can see, this particular copy has not had a quiet life tucked away on library shelves - it looks like it’s been used for quite a bit of penmanship practice by previous owners! Once books arrive in our library, we don’t allow users to leave personalized marks, but it’s always fun to find traces that tells us about a book’s past, even the ones that might seem somewhat irreverent.

Post link

English 9CT Antique Victorian ROSE Gold LOCKET Double-Sided Glass Birmingham Hallmarks Signed Makers Mark JS Date 1851

Post link

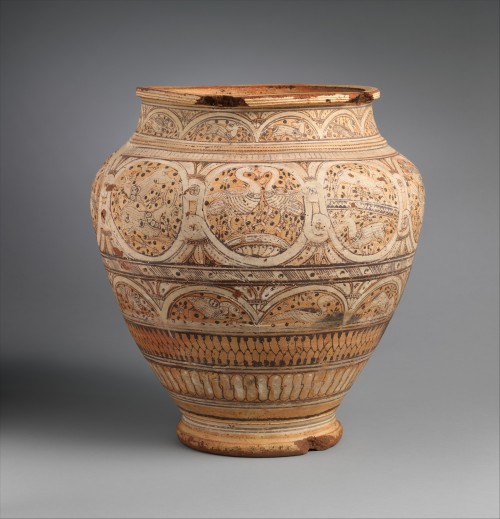

Today is the International Day of Provenance Research! Recognized on the second Wednesday of April, it gives us an opportunity to honor the ancient history of trade and innovation of artwork and objects alike.

Take this jar from the Predynastic Period (ca. 3300–3100 B.C.E.), for example. The inhabitants of the Green Sahara who settled in the Nile Valley began developing some distinct styles of pottery. The geometric shapes decorating this jar were popular among early Nubian potters.The fact that this typically Nubian jar was excavated in El Masaid, Egypt, located just north of modern Luxor, shows that Egyptians prized, imported, and imitated Nubian pottery.

If you didn’t manage to get tickets to tonight’s Curator Talk with curators Annissa Malvoisin and Yekaterina Barbash on Ancient Nubian and Egyptian Vessels, you can learn more about the history of artworks like this in “African Ancestors of Egypt and Nubia: From the Green Sahara to the Nile.” Now on view in the Egyptian Galleries.

Jar with Impressed and Incised Decoration, ca. 3300-3100 B.C.E. Clay, paste. Brooklyn Museum, Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 09.889.445. Creative Commons-BY

Post link

Lacquer Box with Crabs, Waves and Flowers, Japan, 17th century 江戸時代 蟹波蒔絵箱

Provenance: Klaus F. Naumann, Tokyo, until 1989; sold to Irving]; Florence and Herbert Irving, New York (1989–2015; donated to MMA)

H. 6 ¾ in. (17.1 cm); W .6 in. (15.2 cm); L.12 ½ in. (31.8 cm)

Post link

Ceramic Jar painted with plants, birds and other animals, Egypt, 7th century

Provenance: Nicolas Tano, Cairo, until 1922; sold to MMA

H. 19 7/16 in. (49.4 cm)

Post link

Ceramic Box in the Shape of a Turtle, Manufacturer: Minton and Company, 1871

Provenance: Helene Fortunoff, North Hills, N.Y., by 2015; Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Conn.

2 ½ × 4 ¾ × 3 ¼ in. (6.35 × 12.07 × 8.26 cm)

Mintons was a major pottery company at the Staffordshire Potteries which was founded by Thomas Minton (1765–1836) in 1793. It became highly popular during the Victorian era and remained and independent business until 1968. Mintons produced various ceramic designs in Historiciststyles using different decorative techniques. Apart from vessels and sculptures the firm also manufactured tiles and other architectural ceramics for both the Houses of Parliament in London and United States Capitol.

[text source: @wikipedia]

Post link

The Freezing of the Sea, Antarctica, Herbert G. Ponting , 1911

Provenance: Samuel Wagstaff, Jr., American, 1921 - 1987, sold to the J. Paul Getty Museum, 1984.

75.3 × 59.8 cm (29 5/8 × 23 9/16 in.)

Herbert George Ponting ( 1870 – 1935) was a professional photographer. He is best known as the expedition photographer and cinematographer for Robert Falcon Scott’s Terra Nova Expedition to the Ross Sea and South Pole (1910–1913). As a member of the shore party in he helped set up the winter camp at Cape Evans which included a tiny darkroom where Ponting preferred to take high-quality images on glass plates.

[text source: @wikipedia]

Post link

Dish with floral design, Japan, late 17th century

Provenance: William K. Bixby Trust for Asian Art

H 3.8 cm x Ø 15.6 cm

William K. Bixby(1857-1931) was an American collector of art and rare books, and is known for his significant philanthropic contributions around the St. Louis area. He worked through the ranks of the Texas railroad and his vigor caught the eye of H.M. Hoxie, the president of the Missouri Pacific Railroad. Hoxie soon convinced Bixby to move to St. Louis to work for the Union Pacific, and in 1889, Bixby spearheaded the merger of eighteen companies that led to the creation of the American Car & Foundry Company.

In the year preceding his retirement, he headed the Fine Arts Commission for the 1904 World’s Fair, an act that helped inspire the creation of the St. Louis Art Museum. He was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1906. He donated items such as The Nuremberg Chronicle, 1493, papers of Thomas Jefferson, and an illuminated Medieval Missal leaf to the Missouri Historical Society. He also donated parts of his collections to the St. Louis Art Museum, Washington University in St. Louis, the St. Louis Mercantile Library, and the St. Louis Artist’s Guild, among others.

[text source: @wikipedia]

Post link

Oval etching with 18 animals including unicorn, Martin Pleginck, Germany, 1594

Provenance: museum purchase 1990

h 43mm × b 61mm

Post link

Pegmatitic hornblende diorite stone vessel, Ancient Egypt, 2950-2573 BCE

Provenance: donated by the John Huntington Art and Polytechnic Trust 1914

ø 21.1 cm (8 5/16 in.)

Post link

Jade Bowl, China, 19th century

Provenance: donated by Mr. and Mrs. James Leipner

2 ¾ x 5 3/8 in. (7 x 13.7 cm)

Post link

White and Purple Irises, Katsushika Hokusai 葛飾 北斎, Japan, early 1800s

Provenance: donated by Mrs. Ralph King 1943

70.5 x 19.8 cm (27 ¾ x 7 13/16 in.)

Post link

Round Red Lacquer box, China, 18th century

Provenance: Ralph M. Chait Galleries, Inc. New York, until 1989; sold to Irving]; Florence and Herbert Irving , New York (1989–2015; donated to MMA)

ø 13 ¼ in. (33.7 cm)

The Qianlong Emperor (1711 – 1799) commissioned at least eighteen versions of this lacquer box. He was the sixth Emperor of the Qing dynasty. Like his predecessors, took his cultural role seriously. The Qianlong Emperor was a major patron and important “preserver and restorer” of Confucian culture. He collected ancient bronzes, bronze mirrors, seals, pottery, metal work as well as lacquer work, which flourished during his reign. A substantial part of his collection is in the Percival David Foundation in London.

[text source: @wikipedia]

Post link

The Amida Falls from A Tour of the Waterfalls, Katsushika Hokusai, Japan, 1833

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA)

Provenance: ? - donated by Max Palevsky2011

14 11/16 × 9 7/8 in. (37.31 × 25.08 cm)

Post link

Batik Printing Block, Indonesia, 19th century

The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA)

Provenance: not mentioned on website

13 5/8 × 16 ¾ × 1 ¾ in. (34.61 × 42.55 × 4.45 cm)

Post link

Cat with Kitten, Ancient Egypt, 1069–664 BCE

Provenance: ? - donated by J. Lionberger Davis

height: 1 1/8 in. (2.85 cm)

Post link

Iguana Vessel, Costa Rica, 7th-12th century

Provenance: Update on pre-acquisition history pending.

Base: 15.1 x 35 cm Lid: 29.9 x 38 cm

Post link

Tiger and Moon, Ohara Koson, Japan, ca. 1930

Provenance: donated by J. Perrée 1999

H 362 mm × B 190 mm

Post link

Bowl with Lotus Scrolls 金襴手茶碗, Jingdezhen kilns, China, 1500s

Provenance: [? -1968] Percival David - Sotheby’s, London, October 15, 1968 sale, lot no. 109) / [1968] sold to Severance and Greta Millikin by John Sparks London / [1989] donated by Severance and Greta Millikin to the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Ø 6.4 x 12.1 cm (2 ½ x 4 ¾ in.) Overall: 6.1 cm (2 3/8 in.)

Post link

Scarab Ring, Green Glazed Steatite, Egypt, 1279-1213 BCE

Provenance: Purchased from Mohammed Mohasseb and Son by Lucy Olcott PerkinsthroughHenry W. Kent - donated by the John Huntington Art and Polytechnic Trust 1914

Ø: 2.5 cm (1 in.); Overall: 1.5 cm (9/16 in.)

Post link

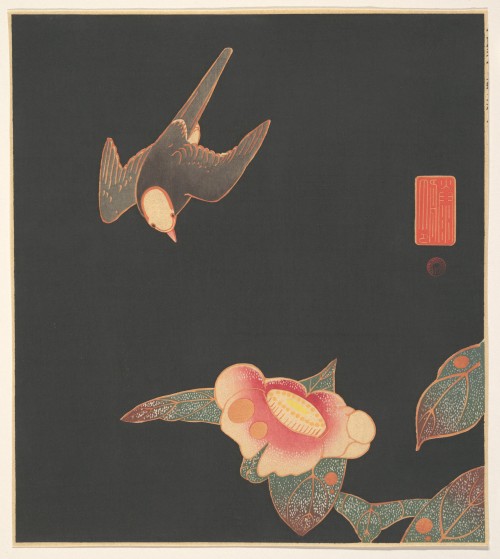

Swallow and Camellia, 伊藤 若冲 Itō Jakuchū, Japan, ca. 1900

Provenance: Mrs. Herbert R. Wilde , Newtown, CT (until 1925; sold to MMA)

9 ¼ x 8 ¼ in. (23.5 x 21 cm)

Post link

Lacquered box with mother-of-pearl inlay, Thailand, early 19th century

Provenance: Sotheby’s London, Indian Sale, May 23, 2006, lot 30 Maxine N. Dunitz Los Angeles - donated to MMA by Dunitz in 2017

H. 4 ½ in. (11.4 cm); W. 24 ½ in. (62.2 cm); D. 4 ½ in. (11.4 cm)

Post link