#motion pictures

NOW KISS!

Edmund Goulding, MGM director, helping William Twiddy and “Bill” Easton kiss while making a film with the motion picture class at Columbia University.

1927.

Post link

Battleground (1949) Directed by William Wellman

“You had a good home when you left; you’re right!”

That’s the march cadence for this squad of the 101st Airborne Division, on their way to Europe, where they will run head on with a counter offensive by the Germans and one of the worst winters on record. The squad won’t be singing for some time.

Ill equipped for winter weather, nearly out of ammunition and food, and trapped in the snowy, impenetrable woods of the Ardenne forest, these “citizen soldiers” (as historian Stephen Ambrose has called them) faced all the misery and deprivation that characterized the Battle of the Bulge. Director “Wild Bill” Wellman (a WWI veteran, stunt flyer, and Hollywood helraiser par excellence) therefore makes certain that we don’t get much to celebrate in this downbeat gem.

The characters are the likable G.I.s found in so many war pictures, but this group isn’t having any fun. Wellman also makes it clear that most G.I.s, courageous and patriotic as they may be, had just as soon not slog around Europe on an extended camping trip. But apart from the standard bitching—an art form for most soldiers—there is the very real fear of freezing to death, encountering surprise enemy fire in the blinding snow and fog, or simply getting separated from the outfit and never being seen again. There’s even the vague suspicion that the German counter offensive is pushing back the allied armies. The camera captures all these worries in numerous closeups of faces. Soldiers can’t hide it.

In the besieged city of Bastogne, the possibility of stemming the onslaught is weighed against remaining ammunition; in the forests, combat takes place in 11-foot banks of snow or among mazes of heavy evergreen branches. Fighting sheer exhaustion is each soldier’s key battle; a mere glimpse of sunlight might constitute a moral victory.

Although actors John Hodiak, Van Heflin, Ricardo Montalban, and a crew of character players do a remarkable job of making it feel authentic, conveying the misery most effectively is James Whitmore as the unforgettable Sergeant Kinnie. He’s a bow-legged, cigar-chomping, grizzled old vet who by God finds the means—and the spirit—to bull his way through all conceivable obstacles. When he notices his shadow in the snow, he almost cries at the revelation.

Now supplies can be flown into the combat zone.

It’s a typical G.I.’s holiday; the possibility of K-rations, new rounds for his M-1, and a blanket. Only a vet like Wellman himself might understand why this little moment is the film’s climax.

Post link

Bad Day at Black Rock (1955) Directed by John Sturges

Any hot summer day is a good excuse to draw the curtains, get the room dark and cool, and watch this mid-century thriller that now stands as a minor masterwork of distinctly American cinema.

In an unforgettable establishing shot, one-armed WWII veteran Spencer Tracy steps off a Southern Pacific streamliner at the far end of the high desert in Nowheresville, California. Actually he’s in Black Rock, a dusty, near-vacant town surrounded on all sides by vast, dry expanses of…well, vast dry expanses.

He’s looking for a Japanese man who lives a few miles away in the mountains, and he’s asking for a ride out to the property. The nine or so town residents, who range in demeanor from weirdly suspicious to full-on menacing, don’t like that idea at all. In fact, these grim heavies (Robert Ryan, Ernest Borgnine, and Lee Marvin as a trio of Post-War rattlesnakes) don’t like Tracy on principle.

After all, this is the first time in four years that train has even slowed down in Black Rock, and this visitor keeps asking about the Japanese guy even after everyone says he should forget about the Japanese guy.

One can’t help suspecting that a kind of storm cloud is building strength way out near the horizon.

The tension grows at an excruciating pace, thanks to a taut script superbly complemented by wide, lingering, but never wasted CinemaScope angles.

(You could almost say this is why CinemaScope cameras were invented and why director John Sturges was born.)

In any case, once Tracy clashes head-on with the town, the moment is like a sudden lightening bolt on a hot, dry day: no wind, no rain, just scorched earth and a cloud of dust.

Post link

The Power of the Dog (Jane Campion, 2021)

I was mesmerized from the first frame. Tension and dread grew from that point. Jane Campion fans may rightly suspect that this is her finest picture; fans of Terrence Malick’s and Paul Thomas Anderson’s pictures will find much to marvel at and compare.

Better still, if you go in big (as I do) for the sheer ambiguity of tense, sparse, and freighted dialogue between characters in, for example, Harold Pinter, Henry James, and certain short stories by Shirley Jackson or Robert Aickman, then this is the ideal setting for sitting at the edge of your seat wondering when disaster may strike.

Or wondering if you can rely on what is presented, or if you can rely on your assessment of same.

Campion juxtaposes the folks in this yarn with vast, sweeping vistas of Very Big Country, as if to demonstrate that, in 1925 Montana, humans were still to some extent facing forces and elements much larger than themselves.

Within a few minutes it becomes apparent that large, uncontrollable, and even devastating forces dwell within those humans.

So no, this is not a cowboy movie. It’s barely a western. It’s instead an exquisitely calibrated melodrama about how appearances still deceive even the most discerning and calculating observer, even if that observer is a brilliant, furious, scheming, and experienced one who is accustomed to spotting weaknesses and manipulating others.

Or especially if.

Post link

Nightmare Alley (2021, Guillermo de Toro)

It’s the luxurious visual spectacle I wish all pictures could be.

That’s no surprise considering the director and anyone involved in set design and art direction that Guillermo del Toro is known for.

Countless shots are suitable for framing (no pun intended) and many of them look like complete lifts from WPA Kodachrome collections at the Library of Congress. It was 1941-43 and I believed it.

Not only is the carnival a fully realized realm with authentic 70 to 100-year-old rides and attractions, ancient show banners, creaky stages, and an iron proscenium laced with neon, but the office spaces and dwellings of the city characters put you in a period that might be called Rococo Art Deco.

Add blankets of snow and all of it’s a dream.

Add the pulp-fiction narrative, however, and all of it is definitely a nightmare.

I know the novel and the first motion picture version of this story front to back, but at times, with this adaptation, I still found myself dreading the next bad decision that Stanton Carlisle (Bradley Cooper with despair in his eyes and a smirk on his face) was bound to to make. The doomsday vibe from this character almost induces claustrophobia.

It’s grim and hellish stuff, and I wonder how the beyond-grim final half hour of this picture comes across to viewers who go into it cold.

It’s possible modern audiences don’t like the slow build, but that would be odd in the era of 4-season, 8-episode Netflix and HBO series.

Numerous reviewers whom I respect have expressed disappointment with this latest from del Toro. Something about enjoying the noir elements, the pulp gloom and danger, and the magnificent dreamlike settings…but wanting more. Wanting “substance” or “life.”

You know what folks who go to carnivals expecting substance and then walk away disappointed are called? They’re called “marks.”

Joint runners can spot them at a distance.

Post link

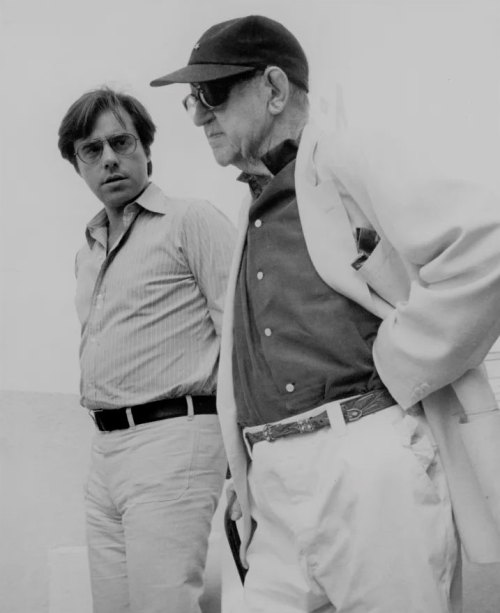

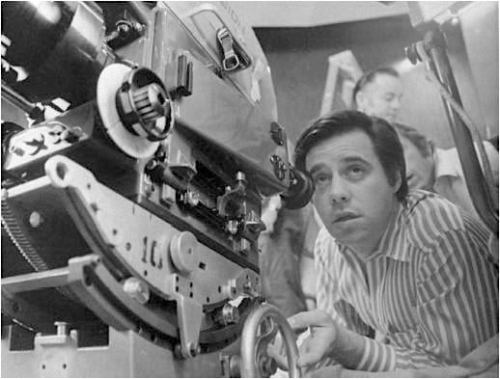

RIP Peter Bogdanovich

“When I was younger, all my friends were older - John Ford, Howard Hawks, Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, Jimmy Stewart, and Cary Grant. I loved talking to those people."

Post link

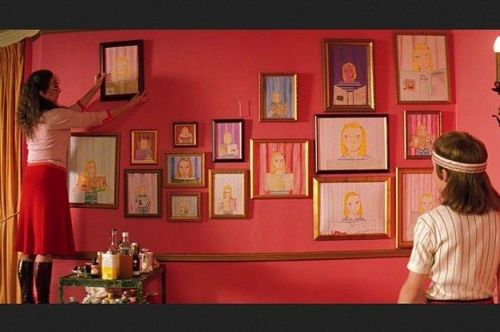

The Royal Tenenbaums (2001, Wes Anderson)

Turns 20 this month, but as with any Wes Anderson picture, that’s a meaningless milestone because, as the director’s work exists in its own peculiar, marvelous realm, it therefore exists in its own time.

The trademarks are on display: rigorously formal, symmetrical compositions (many of which are static tableau), color schemes so complex and thorough that Sherwin-Williams could build collections around them, and attention to detail that is better described as luxuriating in detail. It’s all an overwhelming and hilarious presentation that can induce mild vertigo, but the soundtrack offers breaks into soothing montage that slow the rhythms or establish new ones.

Anderson is a miniaturist operating on a huge scale, lending the illusion that his sprawling universe of subplots, red herrings, arcane references, and ancillary characters exists within a shadowbox or doll house.

Speaking of color schemes, observers have detected that The Royal Tenenbaums functions as a crimson and burgundy salute to Taxi Driver, all in-jokes about the Gypsy Cab Company aside. I see those cascades of red hues and pink compliments as wholly appropriate for a valentine. The browns and creams are a Whitman’s Sampler.

After all, the story is essentially an elaborate construction of Royal’s big valentine: first to his estranged wife, then to his children, and finally to the life he almost had.

Granted, Royal’s valentine is like one of those cards you grab at the pharmacy Hallmark section late on February 14 because you put off—or forgot—the matter. Now you’re in emergency mode. That explains the climactic scene as a long pan of moments on and around a fire engine.

The entire affair can break your crazy mixed-up heart.

Post link

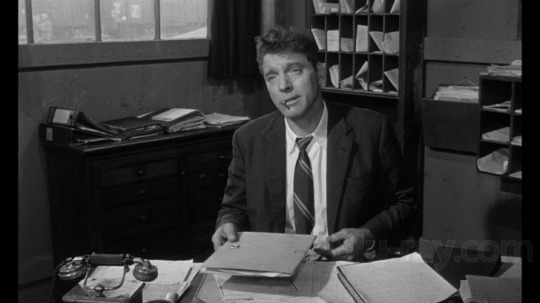

Phantom Lady (1944) Directed by Robert Siodmak

I never get tired of it. It’s not Siodmak’s best picture, but this low-budget gem is a textbook example of an oneiric framework lending substance to an otherwise less-than-believable narrative (supplied by pulp-fiction wizard Cornell Woolrich, whose darkness and weirdness are well established, even for casual noir fans).

DP Woody Bredell’s wild shots and angles are the reason we watch, not least for the legendary jazz club drum sequence, which somehow got past a panel of censors. But there are other pleasures available for keen eyes.

In the quieter moments, such as this scene here, set designer John Goodman and Bredell slyly put in place a series of visual cues that, in retrospect, we recognize as essential tropes of the noir style.

It’s a veritable essay in less than two minutes.

When our suspect takes a seat, we can already see he’s destined to wind up behind bars. Just look at all the stripes in that room and on those suits.

One detective is taking notes on a tiny pad; these literally “little” details of the suspect’s remarks mean nothing in the larger narrative, and the look on that jaded cop’s face indicates it.

Finally our boy rises to defend himself, and look who’s looming over his shoulder. Now that she’s dead, this lady is gonna be a real problem.

But even she has nothing on the phantom lady. And yeah, Ella Raines owns this picture.

Post link

Observe our cinematic heritage long enough and you may notice that, collectively, motion pictures teach us about ghosts. A haunting is merely a ghost busy at work trying to make the ending of any human experience better. Or kinder. Or smarter. Or happy. Or maybe a proper haunting will sufficiently alter circumstances so that there actually is no ending.

In the midst of a haunting we may witness demons and monsters at work, but if that ghost is actually an angel, then every bad spirit is ultimately vanquished by human kindness, decency, and selflessness. We find the happy ending through true moral courage, which is defined as optimism in the face of the worst.

I never suspected that Tarantino would be the filmmaker prepared to celebrate this idea, but there it is. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is a ghost story, one that breaks hearts and lifts them up. All in the effort to haunt that place until the happy ending arrives.

Is it real? Well, ghosts are real, aren’t they?

Post link

(2006) Directed by Steven Shainberg

Director Steven Shainberg and writer Erin Cressida Wilson imagine the world as a kinkier, gentler nation, having collaborated on Secretary(an alarmingly sweet-natured S&M love story) in 2002, and this 2006 furry fantasy starring Nicole Kidman. I absent-mindedly ignored this picture the first time around, somehow overlooking the “imaginary portrait” phrase in the title. The story is not about photographer Diane Arbus’ life, but about a life that might come to mind after viewing her bizarre body of work.

In that context, Shainberg’s picture is an occasionally brilliant display of imagination and romantic sensitivity, as opposed to a highly suspect bio-pic. Critics absolutely shredded it, most of them intimating that they simply couldn’t take any of it seriously. Perhaps that’s because they were taking things too seriously; it’s almost as though no one recognizes a fairy tale anymore. Granted, this is a bedtime story best suited for a sleepover at John Waters’ house.

For those not familiar with Arbus’ photographs, simply recall the twin girls in The Shining, and know that the spooky pair are representative of the Arbus catalog of carnival performers, street people, the mentally and physically handicapped, and just plain weird outsiders and eccentrics. The absence of any Arbus photographs in this movie may be a disappointment for some, but making up for that loss is an abundance of the bizarre characters she encountered during the 1950s and 1960s. For this fantasy, her contact with one outsider evolves into far more than an encounter.

After a few desultory efforts with a camera she borrows from her husband Allan (Ty Burrell), a commercial photographer to whom she is a personal secretary, Diane (pronounced Dee-Ann) the bored housewife/assistant becomes Arbus the inspired artist. Her muse is the man living on the upstairs floor of their apartment building. He’s Lionel Sweeney, an eccentric recluse suffering from a particularly acute case of hypertrichosis, known in the sideshow world as “wolfman syndrome.” Robert Downey, Jr., plays Sweeney, and whether it was originally intended or not, he owns this picture.

Sweeney is a mystery at first, discovered after Arbus finds a key in a drainpipe and ventures upstairs to unlock a strange little door that opens into a loft/curiosity shop. This is where the refined, erudite, and sartorially vain Sweeney has afternoon tea, makes a living selling wigs made from his continuously growing hair, and entertains a coterie of freaks, transvestites, eccentrics, and New York City’s most outré night people. Arbus and Sweeney are at once established as that rare couple who seem intimately connected long before they are intimate. She tells him secrets about her exhibitionist tendencies; he takes her out for nights among the town’s secret enclaves and introduces her to future subjects—not to mention a world with which she is instantly obsessed.

Although this narrative arc blends Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland with Jean Cocteau’s version of Beauty and the Beast, the erotic details call for a Velvet Underground soundtrack that never arrives (that’s taking nothing away from Carter Burwell’s excellent score). Just as the real-life Arbus claimed that art was “a secret about a secret,” this film makes a fetish of fetishes. Yet of all the kinky forays here, the oddest conceit suggests that Arbus’ curious gaze at all the freaks is secondary to Sweeney’s unrelenting, love-struck study of Arbus.

Though it is certainly true that Downey impishly luxuriates in all that head-to-toe hair, and he tricks out his lines with the resonant, mesmerizing tones of a carnival hypnotist, his penetrating eyes are the real side show here. He portrays Sweeney as a creature with the ultimate defense mechanism; no lingering cameras or gawking circus crowds ever gleaned from Sweeney what he can capture with a mere glance. He knows both how to look and what to look for, and with Arbus he has an ideal subject.

Sweeney’s intellect allows him to see the poetry and delightful symmetry in this romance: Arbus thinks she’s the documentarian. Sweeney’s romantic side allows him to spill the beans about their arrangement. Lovingly observing her fascination with his crowd of fellow eccentrics and side show types, he tells Arbus: “All my life I’ve been waiting for a real freak.”

Why We Watch: The Bell Boy (1960, directed by Jerry Lewis)

This might be the most successful sight gag among many in Lewis’ masterwork of minimalism, which offers the physics-defying visual elegance of Jacques Tati, Buster Keaton, and countless Warner Bros. animated classics. Haskell Bogg’s deep-focus camera adds to this picture’s marvelous style and technical mastery, while Lewis (who speaks barely two dozen words) indulges himself with the extended take and the extra gesture.

The Maltese Falcon

(1941) Directed by John Huston

Huston’s detective thriller (and impressive debut) is a bona fide classic, but it’s most enjoyable when private detective Sam Spade (Humphrey Bogart) matches wits with portly thief Kasper Gutman (Sydney Greenstreet) and effete dandy Joel Cairo (Peter Lorre), a deadly pair of fortune hunters in a feverish quest for a valuable statuette called the “black bird.”

The aptly-named Gutman offers phony sophistication and a wise-old-owl act, in the process establishing a prototype for screen villainy by demonstrating the five Cs of the criminal mastermind: courtly, calculating, cunning, cruel, and chatty. When he intones in a phony aristocratic accent to Spade, “By gad, sir, you are a character,” it’s a charming case of the pot flattering the kettle.

Meanwhile Gutman’s, um, “partner,” Cairo nervously rattles off inept threats and homoerotic affectations, all of which amuse Spade. The private eye’s smirking recognition of this pair’s numerous shortcomings provides a joy that is a hallmark of film noir: watching small, desperate men do small, desperate things. Cairo (as only Lorre could convey) is never smaller than when he shrieks his displeasure at Gutman’s error in judgment: “You imbecile! You bloated ee-diot. You stupid fat-head you!

Smallness of character doesn’t stop Kasper Gutman from waxing loopy and grandiose, boasting to Spade:

“I distrust a close-mouthed man. He generally picks the wrong time to talk and says the wrong things. Talking’s something you can’t do judiciously, unless you keep in practice. I’ll tell you right out, I am a man who likes talking to a man who likes to talk.”

Spade undercuts that pompous blather with “Swell. Let’s talk about the bird.”

This talkative hero-versus-villain standoff would be co-opted decades later for the entire James Bond series and its countless imitators. What would never be imitated is the marvelous, legendary chemistry between Greenstreet and Lorre, the pairing of whom is a grand legacy of Warner Bros.’ golden era.

Post link

Phantom Thread (2017) Directed by Paul Thomas Anderson

Paul Thomas Anderson has never not placed directly on the screen all the evidence we need to understand what his pictures are about. (That’s apart from his movie being about his movies, in the same way that a Wallace Stevens poem is so often about the poem itself.)

However, viewers of Anderson’s work are obligated to know some history.

For example, an awareness of how the early self-help, personal improvement cults were marketed to GIs returning from the WWII is essential for complete immersion in The Master. The ads in Popular Mechanics, circa 1949, are practically a program guide.

ForPhantom Thread, a cursory glance at mid-century haute couture, specifically as captured by Norman Parkinson for Vogue at its peak, is all that’s required. Norman Parkinson’s then-famous shots of models Dovima or Lisa Fonssagrives were unmitigated fantasies, even as the subjects and their attire functioned as same. (Better still, see Cecil Beaton’s photos of designer Charles James, on whom Daniel Day-Lewis’ character is based.)

The crucial matter is that Anderson lets us briefly witness the worldly affairs of the otherworldly, and it all looks like those fantastic Vogue photos of yore. This is an intimate glimpse of how members of an exclusive couture society did not merely enjoy a life of privilege, but moved through a stunning kind of day-to-day fantasy.

Anderson knows that if we look long enough, eventually the darker, more perverse elements of this existence will emerge as the primary ones. After all, it’s a rare Grimms’ fairy tale that is not, at heart, a grim fairy tale.

Post link

(1964) John Frankenheimer

In this very unique espionage/caper film, which details actual events concerning the French underground’s work during WWII, Paul Scofield plays a craggy, pock-marked S.S. terror who’s loading a Nazi troop train with crates marked “Degas,” “Renoir,” and “Picasso.”

The idea is to get France’s priceless collection out of Paris and into Berlin, what with the Allies just a few miles outside of the city. A civilian railway inspector (Burt Lancaster, gritty and stoic like you won’t believe) has other ideas. He and the French Underground unit he secretly directs have a so-crazy-it-just-might-work plan. It’s so crazy, in fact, that it takes a while for Lancaster to get on board (pun intended) with the underground crew.

A wonderful conceit in this story is that the underground detects that the Nazis’ obsession with bureaucratic efficiency is an Achilles’ heel on their collective jackboot. Anytime there’s a railway delay ( a complete ruse always designed by the underground), some German officer attempts to raise hell. Lancaster simply puffs his cigarette, waves some official papers from the high command, and wearily sighs, “It’s your war. I’m just trying to run a railroad.”

As tense and fiercely energetic as the action is, and as impressive as the stunts may be, there remains a pervasive element of gloom. An impressive supporting cast (Michel Simon, Jeanne Moreau, Wolfgang Preisse) conveys a general air of resignation.

But it’s the rail yard, with its constant noise, steam, and random machine gun executions, that establishes most of the despair here. It functions as an alternative location for Eraserhead with Nazi troops thrown in for effect. Jean Tounier’s black-and-white cinematography, which evokes a stark realm of shiny surfaces, grime, black puddles, and gray skies, must have influenced Schindler’s List.

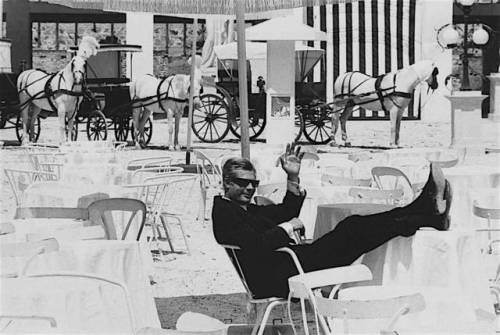

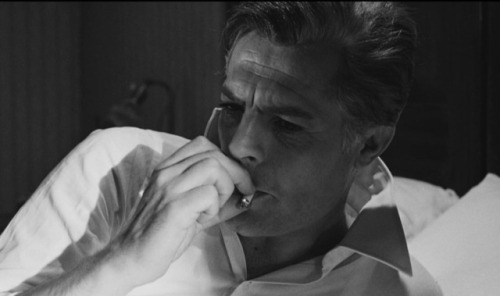

8 ½ (1963) Federico Fellini

The story, such as it is, consists of a director’s flashbacks and fantasies he experiences while in the middle of an emotional and creative crisis. That story is merely a platform for a highly stylized cavalcade of jet-set Eurotrash, wild parties, and a bevy of otherworldly women (Anouk Aimee, Claudia Cardinale, and Barbara Steele, among others). These women come and go, not necessarily speaking of Michelangelo (sorry; couldn’t resist a bad T. S. Eliot pun and reference to that other Italian director).

It’s also a platform for Marcello Mastroianni, the ne plus ultra of Italian cool and possibly the hippest man in the world in 1963. He embodies what functions as a self-portrait of Fellini, effortlessly gliding through a bizarre realm of celebrity and self doubt and self aggrandizement. The supporting cast, too, is something to behold. There are only hints of the European gargoyles who would populate Felinni’s subsequent works, but enough strange faces and voices are present to make indelible impressions.

Woody Allen paid an intricately detailed tribute to this picture with Stardust Memories, in much the same way that Gene Wilder and Mel Brooks sent a Valentine to Universal Pictures’ monster series with Young Frankenstein. But who could resist emulating this oneiric spectacle? Nino Rota’s lilting score and Gianni Di Venanzo’s camera are mesmerizing. And Mastroianni just owns it.

Post link

(1969) Directed by Sergei Paradjanov

“In the temple of cinema there are images, light, and reality. Sergei Paradjanov was the master of that temple.” Jean Luc Godard

It makes for challenging viewing at times, but this astonishing and baffling picture is a deeply moving example of artistic determination and originality.

Now at its 50thanniversary, there is nothing else like it in all of cinema. Paradjanov’s work inevitably inspires viewers afterwards to share, in near ecstatic terms, what they witnessed.

Although the “story” ostensibly details the life of 18th-century Armenian national poet and troubadour Sayat Nova, there is no plot and no narrative. Except in a few instances, the camera does not move, and there is no dialogue. Events do not unfold chronologically. Using even the very loosest definition of “motion picture,” it is accurate to say that a screening of The Color of Pomegranatesdoes not constitute a night at the movies.

In many scenes, which are usually static tableau in which characters move in and out of frame, Paradjanov uses a motion picture camera to recreate religious icon paintings. It is impossible to determine which scenes depict the life of Christ and which deal with Sayat Nova, and so it may be Paradjanov’s intention to conflate the two. More puzzling than the icon tableau are those moments when truly beautiful men and women calmly and resolutely stare directly into the camera while conducting enigmatic rituals or making odd gestures.

The art direction and carefully choreographed action are lovely to behold (credit to designer Stepan Andranikyan and cinematographer Suren Shakhbazyan), but Paradjanov adds an overtly surreal element to these tableau. Objects levitate or disappear, apparel unfolds from bodies, and water flows out of walls. The score, consisting of horn blasts, lutes, lyres, and gorgeous choral pieces, has an ancient quality that lends a somber or sacred tone. A narrator reads Sayat Nova’s poetry, and although his words somehow manage to make the proceedings still more baffling, it is apparent that we are witnessing a deliberate, shamelessly personal blending of cinematic surrealism with Eastern-Orthodox Christian traditions. The result is transcendental.

That isn’t all that Paradjanov deftly blends. The sensual quality of some of his characters is subtle, but when cleverly juxtaposed with religious icons and scenarios, certain gestures evoke a mild eroticism that creates considerable tension. Paradjanov expresses yearning, despair, and ecstasy through this method, and it is easy to forget that these are mostly static images with no dialogue or plot. Combined with excerpts from Nova’s poems, many scenes recall the sensual, ecstatic, and transcendental works of the Sufi mystic poet Jalaluddin Rumi.

In such instances, Paradjanov is blending the sensual with the sacred, the spiritual with the mystical. He ultimately blends Armenian culture and Christian lore into a single, mystical vision. The vision may defy interpretation, but the images are nonetheless indelible. They are in the truest sense a mystical meditation: calm and rigorously organized, yet irrational and ultimately ecstatic.

There are links to this kind of cinematic artistry. Paradjanov happily admitted to an influence by Pasolini (certain scenes in Pomegranates recall The Gospel According to St. Matthew), and there is plenty of influence in evidence by Cocteau, Ray, and Dovzhenko here as well. In turn, Paradjanov influenced his contempories. His work gently hovers over Fellini’s Satyricon andCasanova. Some of the more experimental efforts by Derek Jarman recall a few of Paradjanov’s techniques, and Peter Greenaway’s Prospero’s Books looks in places like a direct homage to The Color of Pomegranates.

Still, in terms of style or effect there is no cinematic effort that comes before it and suggests such a thing, or any that may be placed after it as a next step. This amazing work seems to have simply landed here, which is true of many pure products of the imagination. For imagination, Paradjanov was never lacking, as his memorable comment on what it means to be a director suggests:

“It’s like a child’s adventure. You take the initiative among the other children, creating a mystery. You mould things into shape and create. You dress yourself as Charlie’s aunt or as Hans Christian Andersen’s heroes. Using feathers from a trunk you transform yourself into a rooster or a firebird. You torment people with your artistic delight, scaring mother and grandmother in the middle of the night. This is what directing is. You can’t learn it. You have to be born with it.”

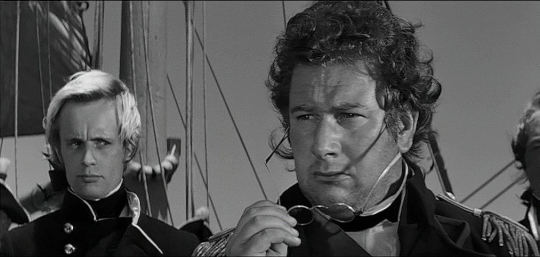

(1962) Directed by Peter Ustinov

Robert Krasker’s (The Third Man,Brief Encounter) excellent black-and-white cinematography, much of which was shot on the high seas, lends a first impression of your standard rousing naval adventure. It’s misleading.

The screenplay adapts Herman Melville’s novella, which should indicate to anyone even slightly familiar with the author’s body of work that this will be a devastating account of human failings and dilemmas.

Billy Budd (Terence Stamp, in the role that initiated his rise to international stardom) is a handsome young sailor—make that a slightly androgynous, stunning example of the Greek ideal of human beauty—whose simple-mindedness borders on mental deficiency. In the eyes of his shipmates (at least those below decks) Billy is just a wholesome country lad probably not ideally suited to life on the British man-o-war the H.M.S. Avenger.

At quarterdeck, the ship’s officers and Post Captain Vere (Peter Ustinov, surprisingly restrained) regard Billy as an admirable seaman who’s perhaps too good for his own good, and that’s all there is to it. However, for Master d’Arms John Claggart (Robert Ryan, as scary as he’s ever been), there are no good sailors. There’s just a crew of ne’er-do-wells who must be controlled by flogging and/or hanging.

Claggart is a sadist with an innate skill at manipulating his intellectual inferiors, and the British navy is a target-rich environment. When Churchill made that remark about rum, sodomy, and the lash, he must have had Claggart in mind.

In any case, Claggart can’t believe that Billy’s unassuming remarks and gentle answers to commands are anything other than a sly effort to mock his superiors. He knows how to break those types, but just imagine his baffled rage when he finally determines that Billy is the genuine article, or more infuriating, an innocent soul.

Claggart fairly vibrates with hatred, but a new type of sailor calls for a new type of manipulation, and he is cunning enough to meet the challenge. In some of the best scenes, the fascinating exchanges between these two recall, not accidentally, Christ being tempted in the desert.

The third act manages to be still more emotionally harrowing. I won’t spoil it, but suffice to say that a moral dilemma ensues. Captain Vere feels duty-bound to follow the law, although his officers sense an imperative to seek actual justice. This scenario might have been a facile ethics lesson (like an episode of “Star Trek”) but Peter Ustinov and DeWitt Bodeen’s brilliant screenplay emphasizes the madness of rigid legal systems.

It’s also clear that any one of these naval officers could argue either side of the debate. Sharpening their understanding merely sharpens their pain, and it might be that particular note of realism that lifts this tale out of the realm of melodrama.

Why We Watch: Ingmar Bergman

As the son of a stern Lutheran minister whose disciplinary measures made Bergman’s childhood a time of fear and resentment, and as a resident of a country in which the very climate itself can induce a lifelong depressed state, the widely acclaimed director was perhaps not well suited for a career in the entertainment industry. But then, the definition of entertainment must be broad indeed if any of Bergman’s work is to fall into that category, unless being mesmerized, inspired, or deeply troubled by a motion picture means we’ve been entertained.

It wasn’t that the themes of his pictures (death, pain, isolation, fear, God, doubt, damnation) were in themselves inherently grim; the dour, downbeat nature of those films derived from Bergman’s resolute, formal, and direct manner of exploring those themes. The most obvious manifestation of his directness was the close-up shot, and casual viewers might mistakenly (but understandably) remember, for example, Persona, as nothing but a series of close-ups of Bibi Andersson and Liv Ullmann. (The two actresses, most assuredly worthy of close-ups, were members of what amounted to Bergman’s stock company). Less obvious at first, but quite moving and memorable over time, is the quiet, deathly still atmosphere of certain scenes. The effect doesn’t lend itself to description, but some quality of that stillness results in immediacy, creating the illusion we are somehow in physical proximity of what transpires. This subtle fly-on-the-wall approach makes many scenes rough going, as nobody wants to be up close and personal during forays into the metaphysics of alienation and anguish.

Then viewers realize that they’ve been tricked into an investment in the proceedings, and not merely because the photographic splendor of these films, usually compliments of cinematographers Gunnar Fischer and Sven Nykvist, has seduced them. What’s going on is a creative feat that for decades countless critics, scholars, and filmmakers have attempted to grasp and/or emulate: the creation of a boldly expressive cinematic style that conveys utter detachment, and the presentation of alienation, inner conflict, and human suffering that is highly engaging and ultimately life-affirming. On paper, these elements should not work together toward those results, but in Bergman’s films they do because, against all odds, the most depressed artist in Sweden found a way to connect with us.

Attempts to fully explicate how that is so are exercises in futility. In fact, it’s extremely hard to definitively state that a particular Bergman film is intriguing, off-putting, engaging, boring, funny, sad, tedious, or scintillating. They are all wholly personal, phenomenal visual experiences with universal impact, and they are usually impossible to ignore. That brilliant sunlight filtered through a forest in The Virgin Spring, the expressionist cinematography that recalls medieval woodcuts in The Seventh Seal; the eerie blending of faces in Persona—those are reasons alone for going to the theatre, purchasing the DVD, or updating a Netflix queue. To that end, see Silence,The Seventh Seal,The Virgin Spring, and Hour of the Wolf.

Reposted for 100th birthday

Movie Haiku of the Week: 2001: A Space Odyssey

Without your helmet,

Dave, you’re going to find that

difficult to do.

Post link

“You are a town man; you do not know the dark ways of the country.”

Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971) Directed by Piers Haggard

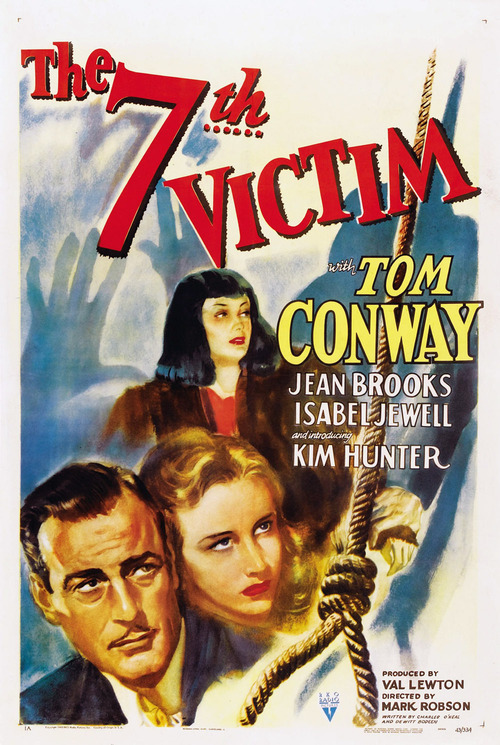

(1943) Directed by Mark Robson

For many cinema enthusiasts, RKO producer Val Lewton’s shimmering, melancholy “dark fantasies” are completely mesmerizing. Martin Scorsese has noted that the producer’s series of horror movies, which feature preoccupations with gloomy ambiguity and obsessive fatalism, was an unrecognized but profound influence on post-war American and European cinema. Though often marred by substandard acting and hampered by low budgets, these productions are small victories of style over constraint. If you wonder what Lewton might have accomplished with unlimited resources, consider that M. Night Shyamalan’s pictures (for better or worse) are largely blends of Spielberg spectacle and Lewton subtlety.

Often working with sterling technicians such as cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca and director Jacques Tourneur, it was an asset, as opposed to a hindrance, that Lewton relied on shadows, suggestion, and distinctly bizarre narratives to chill audiences. By terrifying viewers with their own imaginations, he practically created a sub-genre of thrillers aptly called “psychological horror.”

The grimmest, and in many respects the most sophisticated, of Lewton’s pictures is this despairing tale of a young woman tangled up with a satanic cult in Greenwich Village, of all places. (Apparently Bell, Book, and CandleandRosemary’s Baby owe a debt to Lewton, too.) The production is far ahead of its time in dealing with such melancholy themes as the occult, suicide, and prostitution—as well as in complementing all that gloom via Musuraca’s camera, which is obviously establishing the early visual components of RKO’s trademark noir style.

Mark Robson, having learned a few tricks as an editor or director for some previous Lewton pictures, applies his share of flourishes to the matters at hand (leaving us to wonder what happened years later with The Valley of the DollsandEarthquake). The main attraction, however, is the unrelenting romanticism with which this extremely unusual, complex Manhattan tale is told. That’s to be expected from a picture that opens with the John Donne quote: “I run to death, and death meets me as fast,and all my pleasures are like yesterday…”.

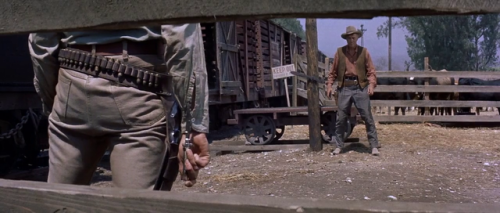

The Magnificent Seven

(1960) Directed by John Sturges.

Everyone knows the first notes of Elmer Bernstein’s rousing score.

In addition, who doesn’t like a picture by John Sturges, that manly maker of man-sized action movies? And this one’s more than man-sized, filling big screens with Charles Lang’s stunning Panavision cinematography.

Granted, there’s a generation of folks today who simply will not watch a western, but think of this picture as a fable and it takes on a different texture altogether (it’s based on Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai, after all).

This is also an opportunity to see some major actors such as Steve McQueen, James Coburn, and Charles Bronson before they became mega-stars.

A shiny-bald Yul Brynner is the man in black, leader of six gunslingers who rescue a poor Mexican village from a vicious band of, well, bandoleros.

Eli Wallach is the head bandito, and he pretty much makes this his picture at times, if only because of his wicked sense of humor.

Nonetheless, other players have their moments, specifically Coburn, who can pull a knife from behind his neck and throw it before anyone else can draw a Colt revolver. As for those neat little tricks with a shotgun by which Steve McQueen frequently shows off—he was doing them to upstage Brynner.

Robert Vaughn (soon to be Napoleon Solo in “The Man From U.N.C.L.E.”) is the best dressed among the seven (excluding Brynner), with tailored city-slicker duds and accoutrement.

Bronson, not surprisingly, is a brooding badass with a heart of gold.

Yes, this is a guy film.

Post link

1985, Directed by Paul Schrader

A joint venture by producers George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola would never look like this were it not helmed by Paul Schrader, a writer and director whose various works comprise a kind of shrine to the outré, the peculiar, and the despairing. The Schrader/Harold Pinter collaboration for The Kindness of Strangers, along with Schrader’s screenplays for Obsession and Taxi Driver, are prominent elements in the oeuvre, but this highly stylized biography of Japanese novelist and playwright Yukio Mishima is actually a shrine.

That may be because Schrader sees in Mishima’s brooding, odd works the expression of a kindred spirit, but also because he finds a sense of inevitability in the novelist’s life. Schrader is not vaguely interested in explanations, but focuses instead on presentation. Eiko Ishioka’s fantastic sets, John Bailey’s stunning cinematography, and a transcendent score by Philip Glass render a dreamlike scenario that at times seems less motion picture than multimedia installation.

Flashback narration (by Roy Scheider) linking the so-called four chapters of Mishima’s career provides an apt metaphorical device, because it’s impossible to distinguish portions of Mishima’s novels from moments in his real life. This formal style seems influenced by (if not derived from) Peter Greenaway’s films of the same period, so don’t go into this expecting a standard biopic.

It is time to get real about virtual reality. From film to game development, VR has tiptoed its way across industries, introducing a new wave of creativity nurtured by the growth of advanced technology. Created by the Schools of Motion Pictures & TelevisionandCommunications & Media Technologies, Academy of Art University’s VR program provides students the guidance and tools to unlock a storytelling experience that’s making its rounds across the entertainment industry.

“360 video production is the new frontier, representing a dramatic evolution of cinematic language,” Jack Perez, VR instructor and film director, said in an interviewwithAcademy Art U News. “Both filmmakers and audiences are suddenly ravenous for this heightened level of immersion. We want our students to ride the crest of this new wave.”

In addition to offering VR classes, the Academy brings students closer to the VR world by engaging them with professionals in the field. In December 2016, Academy of Art University hosted its second VR Summit to demonstrate the latest technologies and practices emerging in the industry. The summit featured a panel of guest speakers from leading companies such as Jaunt, Oculus VR, and Zeality, and premiered projects created by advanced VR students.

“There is nothing to stop students from making the next VR masterpiece in a better way of doing something that no one else has figured out yet,” Andy Wood, production manager at Oculus Story Studio, said at the VR Summit. “Academy of Art University has a lot of VR equipment that students have access to, and it’s exciting to see what students can do with that.”

As the Academy continues to bring students closer to more immersive media, graduates university have already earned recognition for their work in the tech space. In September 2016, Oculus Story Studio announced its short VR film Henryhad won an Emmy award for “Outstanding Original Interactive Program.” Directed by Pixar veteran Ramirio Lopez Dau, Henry tells the story of a lonely hedgehog who throws himself a birthday party. The film proves there is emotional connection fostered in VR that is different from what users experience when they watch movies or TV. Among the Academy alumni who worked on Henryare Alyce Tzue (‘14, MFA), Bruna Berford ('14, BFA), Kyle Remus ('15, BFA), Moe Myint Htet ('13, BFA), Beibei Gu ('14, BFA), and Sophie Evans ('15, BFA).

We spoke with Berford and Gu about their work on Henryand how their time learning at the Academy shaped them for the professional world!

ArtU: What were your role and responsibilities in supporting the production of Henry?

Bruna Berford ('14, BFA): I joined Oculus Story Studio back on January 2015, to work as an Animator on Henry. As part of the role, I tested the rigs, explored character personality doing quick animation tests, helped translate the 2D animatic into a VR layout and animated long sequences of the main character Henry.

Beibei Gu ('14, BFA): I worked as a Surfacing Artist on Henry. I was introduced to the team by the lovely director of Soar Alyce Tzue, who’s also a good friend of mine. I worked on the project for roughly three months. My main responsibility was UV mapping and painting texture maps, then apply them to the character and environment in Unreal Engine.

ArtU: How did your experience at the Academy of Art University prepare you for the work demands of Henry?

BB:Taking the Pixar classes at the Academy for two straight years was fundamental to me, as they prepared me to face a real top quality animation environment—[giving me the chance to] receive critiques and to take my work to a higher level, focusing on my ideas and performance and not only the physicality part of animation. The transition from being a student to being a professional animator was smoother.

Also, being part of collaborative projects at the Academy helped me improve what I consider to be the basic foundation of professionalism: to be part of a team, to communicate well with my co-workers, to follow deadlines, to be responsible for what I do and organized on a working environment.

BG:I have to say Academy of Art University was the start of it all. StudioX was the reason why I got to where I am today, and Derek Flood was the person who recognized my talent and shaped it into the skill set that got me all these amazing opportunities.

I want to let anyone who’s considering joining StudioX at the Academy right now know how lucky you guys are, and don’t ever let that chance go. The projects you’ll be working on right now might seem so insignificant, the experience could get frustrating and make you doubt if it’s worth your time, but stick it out, you won’t regret it. Without the two years I spent in StudioX, I’d never got the chance to work with Oculus Story Studio.

ArtU: How does this Emmy win impact the conversation surrounding the VR experience?

BB:Storytelling in VR is in its infancy and having this recognition, that we can indeed create an emotional connection with a virtual character and transport the viewer to another world, is groundbreaking. This Emmy puts VR storytelling on the map and shows the world that this is just the beginning. It encourages other VR storytellers to explore and push the boundaries of entertainment, and that is huge.

BG:VR has been a major topic throughout the last couple years. With the Emmy win, I definitely got asked a lot of questions about what exactly is Henry. So even though VR was already a popular uprising topic before, it has certainly raised more curiosity among people who usually don’t play much attention to CG or technology.

Learn about how you can get involved with the Academy’s Schools of Motion Pictures & TelevisionandCommunications & Media Technologies!