#horror cinema

The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971, Robert Fuest)

I guess the Halloween season is a perfect time to note the 50th anniversary of this campy, clever vehicle for Vincent Price.

It’s some silly fun that uniquely combines an Art Deco aesthetic with the adolescent grand guignol vibe of E.C. Comics. Basil Kirchin’s lush score adds to the richness. There are all kinds of winking, knowing flourishes throughout. Having the investigators berated at one point for showing up only after someone else gets dead is a sly, inside jibe at the director, who helmed a few episodes of the iconic British TV crime series “The Avengers.”

Another nice touch is the clockwork “house band” for Dr. Anton Phibes’ palatial estate. Or the curtains on each door and window of Phibes’ Rolls-Royce, illustrated with side and rear views of the man himself (Wes Anderson, take note). Any time that limo heads out across the English countryside, well, it’s not for a Sunday drive.

There were complaints at the time that Vincent Price’s most distinct quality, his voice, could not be exploited for this character. Price compensates, however, with his eyes, a few odd pauses, and a menacing, fully theatrical physicality.

For example, Phibes observes from a distance (via telescope) a victim’s biplane that he’s tricked out with another elaborate trap. When the plane makes a fiery crash, he swirls the telescope on its tripod and begins applauding.

But if we come to this picture to see the mad doctor, we stay for the even more bizarre Vulnavia, who is Phibes’ surgical assistant and devoted Girl Friday.

She’s especially captivating when sweeping the ballroom after hours, or when she’s out for an afternoon fall stroll.

Yes, Vulnavia’s a murderous little minx with ice in her veins, but style points where style points are due, I always say. She was born to wear that black fur ushanka and velvet cape with brocade appointments—and her handsome little greyhound sports a suede collar. Vulnavia was an artist with fox fur—even during off days.

I think of her whenever it snows.

Post link

Halloween (1978, Directed by John Carpenter)

The sequels are all unwatchable, and the original itself is a tired reference point and inspiration for a lazy slew of slasher films (and their parodies).

It’s enough to put anyone off of the original, which just happens to be a fine little shocker, not to mention a film-school primer in audience manipulation. Indeed, in 1978 director John Carpenter manipulated viewers like no one had done since Hitchcock traumatized the nation with Psycho.

That’s fitting, as Carpenter uses Psycho as a kind of foundation. Janet Leigh’s daughter, Jamie Lee Curtis, is the heroine, and Donald Pleasance plays a psychiatrist named Sam Loomis (the name of Leigh’s paramour in Psycho). There are some other in-jokes, but more significantly, Carpenter establishes from the start that we are dealing with a slicing-and-dicing homicidal maniac, and then spends the remainder of the evening having that very human monster lunge in and out of the Panavison frame—or maybe just loom in the corner.

We fully understand how a psycho behaves, and Carpenter uses that against us. The film would probably not have been greatly altered if, at some point, the director walked into frame, turned to the camera, and stated, “I’m toying with you; enjoy the rest of the show.”

Thanks to cinematography that’s as crisp as a fall afternoon, the Panavision lens also captures an unsurpassed setting for a horror film so inextricably linked to urban legend. The jack-o’-lanterns, the golden leaves—all artificial, by the way—blowing across the sidewalks and lawns of a solid American suburb, and the tidy front porches evoke our collective Halloween neighborhood. It was producer Irwin Yablans’ idea to call the picture Halloween; irrespective of the first script (The Babysitter Murders), Carpenter could not have possibly used any other title.

Post link

“You are a town man; you do not know the dark ways of the country.”

Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971) Directed by Piers Haggard

I have even more reasons why this marvelously restrained picture remains the gold standard for ghost stories played out on the screen.

The source material from a master of syntactic precision and narrative ambiguity, Henry James; Georges Auric’s haunting (pun intended) score; Freddie Francis is behind the camera and Deborah Kerr is in front of it.

This is a graceful, stunningly effective picture that can put a chill on the most jaded viewers, although it ought to be seen alone on a quiet evening in order to appreciate its delicate spell.

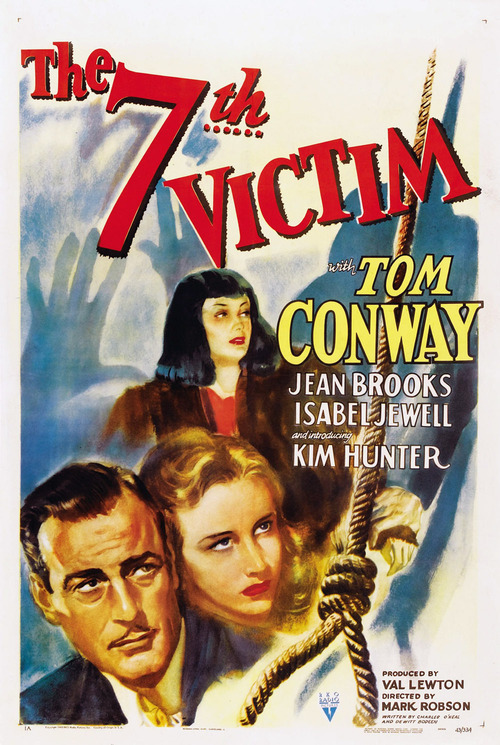

(1943) Directed by Mark Robson

For many cinema enthusiasts, RKO producer Val Lewton’s shimmering, melancholy “dark fantasies” are completely mesmerizing. Martin Scorsese has noted that the producer’s series of horror movies, which feature preoccupations with gloomy ambiguity and obsessive fatalism, was an unrecognized but profound influence on post-war American and European cinema. Though often marred by substandard acting and hampered by low budgets, these productions are small victories of style over constraint. If you wonder what Lewton might have accomplished with unlimited resources, consider that M. Night Shyamalan’s pictures (for better or worse) are largely blends of Spielberg spectacle and Lewton subtlety.

Often working with sterling technicians such as cinematographer Nicholas Musuraca and director Jacques Tourneur, it was an asset, as opposed to a hindrance, that Lewton relied on shadows, suggestion, and distinctly bizarre narratives to chill audiences. By terrifying viewers with their own imaginations, he practically created a sub-genre of thrillers aptly called “psychological horror.”

The grimmest, and in many respects the most sophisticated, of Lewton’s pictures is this despairing tale of a young woman tangled up with a satanic cult in Greenwich Village, of all places. (Apparently Bell, Book, and CandleandRosemary’s Baby owe a debt to Lewton, too.) The production is far ahead of its time in dealing with such melancholy themes as the occult, suicide, and prostitution—as well as in complementing all that gloom via Musuraca’s camera, which is obviously establishing the early visual components of RKO’s trademark noir style.

Mark Robson, having learned a few tricks as an editor or director for some previous Lewton pictures, applies his share of flourishes to the matters at hand (leaving us to wonder what happened years later with The Valley of the DollsandEarthquake). The main attraction, however, is the unrelenting romanticism with which this extremely unusual, complex Manhattan tale is told. That’s to be expected from a picture that opens with the John Donne quote: “I run to death, and death meets me as fast,and all my pleasures are like yesterday…”.