#yukio mishima

La corrupción de un ángel (1971) - Yukio Mishima

Género: Drama, Clásico.

Esta novela fue concluida por Mishima la misma mañana del día de su suicidio. Se inicia con la adopción del joven Toru por parte de Honda, viejo y acaudalado jurista. Toru, prototipo de belleza masculina, frío e imperturbable, evoluciona desde un talante ejemplar hasta alcanzar una sublimación del individualismo de modo cada vez más inhumano y autodestructivo. Una gran novela en donde Mishima expresa su desprecio por el Japón moderno y por el progreso económico, causa de la pérdida de los valores espirituales.

Citas:

“Tal vez, pensaba a veces, él era una bomba de hidrógeno dotada de conciencia. En cualquier caso estaba claro que no era un ser humano.”

“Sólo amaba las imágenes distantes que no fuesen reflejo de sí mismo.”

“Su engaño le había inducido a romper el espejo que tanto le atormentaba y a huir hacia un mundo sin espejos.”

“¿Nadie era aún consciente del hecho de que el mundo se hallaba completamente dominado por el mal? ¿Se conservaba el orden, procedía todo conforme a las leyes sin que se detectara en parte alguna el más ligero rastro de amor? ¿Se sentían las gentes felices bajo su hegemonía? ¿Se había extendido sobre sus cabezas, en forma de poema, la maldad transparente?”

“…tras sus errores y fracasos podía felicitarse de su destreza para ver a través de las máscaras. Su visión no le fallaba en tanto no estuviera nublada por el deseo.”

“La maldad que bañó esa vida había sido la conciencia de sí mismo. Una conciencia de sí mismo que nada sabía de amor, que hacía pedazos sin alzar una mano, que paladeaba la muerte cuando daba lugar a nobles condolencias, que invitaba al mundo a la destrucción al tiempo que buscaba para sí el último momento posible.”

“Le gustaban las personas que se negaban a comprender al mundo.[…]

Necesitaba una locura que entenebreciera su propia claridad. Debería tener junto a sí a alguien que viera de manera completamente diferente todas las cosas que él veía con tal claridad.”

“La imaginación y la lógica son mis armas, más precisas que la naturaleza, el instinto o la experiencia, completamente impermeables en su conciencia de la apariencia y en su acomodación a ésta.”

“He confiado en mí mismo hasta el grado de la tristeza. Me pregunto cuándo incurrí en el hábito de lavarme las manos después de cada roce con la humanidad…”

“Cuando más grande es la disciplina, mayor es la inclinación a la violencia y llego a cansarme de accionar el botón de control. No debo creer en mi propia docilidad. Nadie sabe qué sacrificio constituye para mí mostrarme amable y dócil.”

“Debo ser mi propio soporte y seguir viviendo. Porque siempre me hallo flotando en el aire, resistiéndome a la gravedad, en las fronteras de lo imposible.”

“Pero el sol demasiado brillante del invierno penetra incluso la transparencia de mi corazón. Es en tales instantes cuando me contemplo con alas que no reconocen obstáculos y veo también que nada haré en absoluto con mi vida.

Probablemente lograré la libertad pero una libertad próxima a la muerte.”

Post link

El pálido rostro de Tôru, delicadamente esculpido, era como el hielo. No manifestaba emociones, ni afecto ni lágrimas.

Pero él conocía la felicidad de observar. La Naturaleza se lo había dicho. Ningún ojo puede ser más perspicaz y agudo que el ojo que nada tiene que crear, que no tiene más que mirar. El horizonte invisible más allá del cual no podía penetrar el ojo consciente era mucho más remoto que el horizonte visible. Y todo género de entidades surgían en las regiones visibles y accesibles a la conciencia. El mar, las naves, las nubes, las penínsulas, el rayo, el sol, la luna, las miríadas de estrellas. Si ver es una cita entre el ojo y el ser, es decir, entre el ser y el ser, entonces debe ser como las imágenes reflejadas de dos seres. No, se trataba de algo más. De ver más allá del ser, de cobrar alas como un pájaro. Transportaba a Tôru a un reino invisible para los demás. Allí incluso la belleza poseía unos confines podridos y costrosos. Tenía que haber un mar nunca profanado por el ser, un mar sobre el que jamás aparecieran los barcos. Tenía que haber un reino en donde en el límite de todas las capas diáfanas nada surgiera, nunca un reino de añil sólido y firme en donde la visión se despojara de todas las argollas de la conciencia y se tornara transparente, en donde los fenómenos y la conciencia se disolvieran como el óxido plúmbico en ácido acético.

Para Tôru la felicidad consistía en lanzar sus ojos hasta tales distancias.

Yukio Mishima

La corrupción de un ángel(1971)

He experimentado el orgullo y el placer íntimos de ver cobrar forma gradualmente el concepto en el horizonte. He puesto allí mi mano desde fuera del mundo y he creado algo y no he saboreado la sensación de ser arrastrado al mundo. No me he sentido recogido como la ropa lavada cuando llega un aguacero. Ninguna lluvia ha caído que me diera existencia dentro del mundo. Al borde del anegamiento intelectual, mi claridad se ha mostrado segura del oportuno rescate de los sentidos. Porque la nave ha cruzado siempre. Jamás se ha detenido. Los vientos marinos han trocado todo en mármol veteado, el sol ha mudado en cristal el corazón.

He confiado en mí mismo hasta el grado de la tristeza.

Yukio Mishima

La corrupción de un ángel(1971)

¿De dónde proceden las dificultades en mi existencia? ¿O por decirlo de otra manera, la ominosa tersura y disposición de mi existencia?

A veces pienso que semejante serenidad se debe al hecho de que mi existencia es una imposibilidad lógica.

No es que yo formule a mi ser difíciles preguntas. Vivo y me muevo sin un poder motivador pero eso es tan imposible como el movimiento perpetuo. Tampoco es mi destino. ¿Cómo puede ser un destino lo imposible?

Parece como si desde el momento en que nací en esta Tierra mi ser supiera que era contra toda razón. No nací con defecto alguno. Nací como un ser humano imposiblemente perfecto, una perfecta película negativa. Pero este mundo está lleno de positivos imperfectos. Sería terrible para ellos revelarme, cambiarme en un positivo. Por eso es por lo que me temen tanto.

Lo que más me ha divertido ha sido el solemne precepto de que sea fiel a mí mismo. Eso es una imposibilidad. Si hubiera tratado de obedecerlo, habría muerto inmediatamente. Sólo hubiera podido significar hacer una unidad del absurdo de mi existencia.

Habrían existido medios de no haber poseído yo dignidad. Sin dignidad habría resultado fácil lograr que otros y yo también aceptáramos todo género de imágenes distorsionadas. ¿Pero es tan humano ser desesperadamente monstruoso? Aunque desde luego el mundo se siente seguro cuando lo monstruoso es realidad.

Soy muy cauteloso pero me falta en gran medida el instinto de autoconservación. Y tanto me falta que a veces me embriaga la brisa a través del foso. Como el peligro es lo habitual, no existen crisis. Bien está tener un sentido del equilibrio porque no me es posible vivir sin un milagroso género de equilibrio; pero de repente se torna en un cálido sueño de desequilibrio y colapso. Cuando más grande es la disciplina, mayor es la inclinación a la violencia y llego a cansarme de accionar el botón de control. No debo creer en mi propia docilidad. Nadie sabe qué sacrificio constituye para mí mostrarme amable y dócil.

Pero mi vida ha sido sólo deber. He sido como un torpe grumete. Sólo gracias a los mareos y las náuseas he podido sustraerme al deber. La náusea correspondía a lo que el mundo llamaba amor.

Yukio Mishima

La corrupción de un ángel(1971)

Sí. Las olas, al romperse, constituían una clara visión de la muerte. Así se le antojaban a él. Bocas entreabiertas en el instante de la muerte.

Jadeando en la agonía, vertían innumerables hilos de saliva. En el crepúsculo la púrpura terrestre se trocaba en una boca lívida.

En la boca entreabierta del mar se hundía la muerte. Mostrando una y otra vez, al desnudo, la muerte, el mar era como una fuerza de policía. Rápidamente disponía de los cuerpos, ocultándolos a las miradas de la gente.

El catalejo de Tôru captó algo que no debería estar allí.

De repente sintió que un mundo distinto era extraído de aquellas mandíbulas entreabiertas. Como no era dado a ver fantasmas, parecía indudable que existía aquello. Pero ignoraba qué era. Tal vez se trataba de una trama formada por organismos microscópicos en el mar. Un mundo diferente aparecía a la luz que centelleaba en las oscuras profundidades y él sabía que era un lugar que conocía. Quizás tuviera algo que ver con recuerdos incalculablemente lejanos. Si existía una vida anterior, entonces se trataba de eso. ¿Y cuál sería su relación con el mundo que Tôru estaba constantemente buscando, un paso más allá del horizonte? Si era un juego de algas marinas en los vientres de las olas al romperse, entonces quizás el mundo entrevisto en aquel instante constituía una miniatura de las rosáceas y purpúreas grietas y cavidades viscosas de las hediondas profundidades. ¿Pero existían los resplandores y centelleos de un mar atravesado por los rayos? No era posible tal cosa en aquel tranquilo mar del crepúsculo. Nada había que exigiera que aquel mundo y este mundo fuesen contemporáneos. ¿Se hallaba en un tiempo diferente el mundo que había atisbado? ¿En un tiempo distinto del medido por su reloj?

Yukio Mishima

La corrupción de un ángel(1971)

Imagen: Ansel Adams

Post link

¿Y cuáles son los cinco signos de la caída del ángel?

Cuando un ángel se remonta y revolotea emite por lo común una música tan bella como ninguna música, ninguna orquesta y ningún coro podrían imitar; pero cuando la muerte se aproxima, la música se extingue y la voz se torna tensa y débil.

En tiempos normales, tanto de día como de noche, fluye del interior de un ángel una luz que no admite penumbra, pero cuando la muerte se acerca la luz se debilita de repente y el cuerpo se envuelve en tenues sombras.

La piel de un ángel es tersa y se halla bien ungida e incluso si se sumerge en un lago de ambrosía rechaza el líquido como hace la hoja del loto; pero cuando se acerca la muerte, el agua se adhiere y no se desprende.

La mayoría de las veces un ángel, como un molinete de fuego, ni se detiene ni es asible en lugar alguno, está allí y aquí casi al mismo tiempo, se escabulle, se mueve y escapa, pero cuando la muerte se aproxima permanece en un lugar y no puede huir.

Un ángel transpira una fuerza que jamás parpadea, pero cuando la muerte se acerca la fuerza desaparece y el parpadeo se torna incesante.

Éstos son los cinco signos mayores: las túnicas antaño inmaculadas se tornan sucias, las flores de la corona se ajan y caen, el sudor brota de las axilas, un fétido hedor envuelve el cuerpo, el ángel ya no es feliz en su propio lugar.

Yukio Mishima

La corrupción de un ángel(1971)

Imagen: Andreas Birath

Post link

Un animo spento dà la certezza di poter risolvere tutto.

Yukio Mishima, La scuola della carne

Dogs, too, barked fiercely from place to place. They were like a band of thieves, each tied up separate from the others, all gnashing their teeth at the ignominy of their bonds and exchanging shouts with one another.

Yukio Mishima, Forbidden Colors (Trans. Alfred H. Marks)

“It was not the reality of defeat. Instead, for me—for me alone—it meant that fearful days were beginning. It meant that, whether I would or no, and despite everything that had deceived me into believing such a day would never come, the very next day I must begin that “everyday life” of a member of human society. How the mere words made me tremble!”— Confessions of a Mask, Yukio Mishima

“I could hear the rain on the eaves. It sounded as if it were only raining on this particular spot. To my ears the rain seemed petrified with fear, as though it had wandered astray in this particular part of the town and utterly lost its way. The sound of the rain was cut off from the vast night, just as I was; it was a sound that belonged to a circumscribed world, like the little world that was illuminated by the dim light of the bed lamp.”

Yukio Mishima| The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (Alfred A. Knopf, 1959)

(via memoryslandscape)

Still from Yūkoku (Patriotism/The Rite of Love & Death) directed by Yukio Mishima, 1966

Illustrations from Gakushuin Elementary School magazine “Kozakura” issue published by Yukio Hiraoka (set of 11 volumes)

With poems by Yukio Mishima

Post link

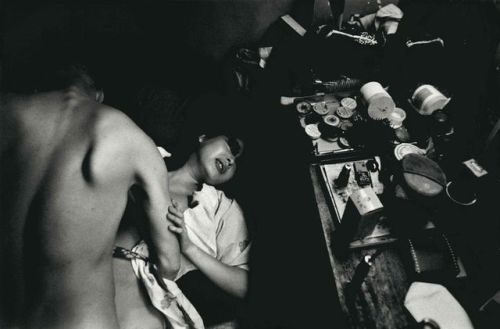

• Blood and Rose, Tokyo, 1969 - Shomei Tomatsu

“Dreams, memories, the sacred–they are all alike in that they are beyond our grasp. Once we are even marginally separated from what we can touch, the object is sanctified; it acquires the beauty of the unattainable, the quality of the miraculous. Everything, really, has this quality of sacredness, but we can desecrate it at a touch. How strange man is! His touch defiles and yet he contains the source of miracles.”

- Yukio Mishima

Post link

I’ll save you the click: as we know, women were once the marked category in contrast to the universal category, i.e., men. But the marked category has been universalized in elite spaces as the new elite status (albeit with its elitism cynically disavowed) to replace the universal status previously enjoyed by men qua men. Men, she therefore argues, must now read and write as marked, which is to say, as “women”—on this account, frail, humble, domestic, and unambitious, since the antonyms of these words have been deemed by our new elite permanently elitist (patriarchal, fascist, imperialist etc.)

Humility is the final guise of a killing hubris, my very least favorite of all the available impostures: “He who humbleth himself wishes to be exalted.” And whoever writes without immodest ambition, without a healthy measure of arrogance, is not worth reading for a single second. Such writers are straightforwardly lying to you about what it takes to write a book (intense self-trust) and the motives involved (an immoderate design on the public’s mind and mood).

What these matters have to do with sex and gender is infinitely complicated and finally unresolvable, as the mystery of what men and women mean to each other always is, despite the simplistic solutions offered by every political faction, feminist or masculinist. Consider the problem posed for the above argument by the well-known fact that men invented the sentimental novel. In my essay on Yukio Mishima’s own masculinist testament, I did consider the likely unpleasant consequence of expelling men from the arts unless they conform to some inverted gnostic conception of mutilated female virtue; but then the sad truth about mainstream publishing (likewise academia and journalism) is that women have inherited a kingdom in decline, while men have piratically taken to the roads and the seas to seek life elsewhere, everywhere from the digital utopia of the blockchain to the new right-wing demimonde. I assume when she says “men need to read more novels,” she doesn’t mean Zero HP Lovecraft or even Delicious Tacos, but that’s where we are.

I am interested in the folly and grandeur of those men and women who wanted to take on the cosmos in their works, the Herman Melville who said that to write a mighty book you need a might theme and the Toni Morrison who answered the old desert-island question by saying she would write her own fiction to read if ever she found herself a castaway. Or the much-misunderstood Virginia Woolf, who correctly preserved for literature male and female as categories both marked and universal, and who therefore wrote this:

Here was a woman about the year 1800 writing without hate, without bitterness, without fear, without protest, without preaching. That was how Shakespeare wrote, I thought, looking at Antony and Cleopatra; and when people compare Shakespeare and Jane Austen, they may mean that the minds of both had consumed all impediments; and for that reason we do not know Jane Austen and we do not know Shakespeare, and for that reason Jane Austen pervades every word that she wrote, and so does Shakespeare.

Post link

—Anne Fernihough, “Introduction,” The Rainbow by D. H. Lawrence (Penguin, 1995)

I didn’t have room to quote the above in my essay, just published yesterday, on Lawrence’s The Rainbow, but you can take it as my epigraph. In my treatment of the subject, I first suggest that a paradigmatic female modernist like Woolf, insofar as she was a modernist, was no less a partner in this “suppression…of political movements” (and the same goes for Stein, Barnes, Moore, Loy, and more, to varying degrees all non-leftists or even in some cases rightists). Then I go so far as to defend the instinct that won out here: the higher politics of the aesthetic over the low politics of mass movements with their designs on state power. Needless to say, this is a very timely prior instance of the same decoupling of bohemian from activist, of aesthetics from militancy, that we see today.

Speaking of all that, while mainstream elite culture is having a D. H. Lawrence moment, I’m surprised he’s not more present in the online extremist countercultures. He has that same Mishima quality, anticipating extremely-online male social outcasts, of being somehow perfectly poised between trans and Nazi, now dipping toward one side, now to the other, but somehow always keeping a precarious balance, in the art if not the life, the would-be mail-fisted fascist as tremulous adolescent girl. I think of how John Carey, in his roll-call of modernist fascism The Intellectuals and the Masses, pauses to exonerate Lawrence of his more troubling tendencies on the grounds that he was, in the end, just a sensitive soul who read Neech too early:

It must be stressed that Lawrence, for all his Nietzschean debts, was not like Nietzsche. The range and subtlety of his imagination went far beyond Nietzsche’s. The Nietzschean warrior ideal, and countenancing of cruelty, could only have seemed disgusting to Lawrence, who turns his characters not into warriors but into flowers. […] To cite such passages—and there are hundreds of them in Lawrence—and to contemplate the impossibility of Nietzsche having written them, is not just to emphasize that Lawrence was a poet and that Nietzsche was in some respects a desperately restricted and unfulfilled human being. It is also to contend that, for Lawrence, the stance of natural aristocrat, with its presuppositions of isolation and alienation, was adverse to all the promptings of his sympathetic imagination, which taught him to fuse and integrate.

The Rainbow is too long, but someone please make the NEETs read “Medlars and Sorb Apples” or “The Prussian Officer” at least. (Why does Mishima get all the attention? Strange that even fringe culture is dominated by the annoying presumption that if it’s translated it must be better.) In my essay I quote this passage from The Rainbow:

She never felt sorry for what she had done, she never forgave those who had made her guilty. If he had said to her, “Why, Ursula, did you trample my carefully-made bed?” that would have hurt her to the quick, and she would have done anything for him. But she was always tormented by the unreality of outside things. The earth was to walk on. Why must she avoid a certain patch, just because it was called a seed-bed? It was the earth to walk on. This was her instinctive assumption.

Here is my official comment, perhaps too Bloomian in its excited swoop through the canon:

Here we remember that Lawrence is the Englishman who put the gnostic-individualist literature of American Romanticism on modernism’s map. Ursula might be the daughter of Hester Prynne and Captain Ahab, her adventures chronicled by a prose Whitman.

My unofficial comment is that this is possibly my favorite paragraph from the novel because it expresses (I confess!) exactly how I felt as a child.

Post link

“Avevo paura di stare da solo. Ora ho paura di avere le persone sbagliate al mio fianco.”— Yukio Mishima

Grammar Breakdown:

Avevo - I used to have (lit.)

in this case the expression “avere paura”, to be afraid, is in the indicative imperfect. Indicative imperfect can be thought of as a type of past tense, to use for things that perhaps used to happen for a period of time.

- “I used to be afraid of being alone”

Ho paura di avere.. - I am afraid of having…

Again using the expression “avere paura di xyz”, to have fear of/to be afraid of xyz. This time, it is in the present sense, using “ho” for “I have”.

The formula verb + preposition + infinitive is common in Italian, and it’s important to know which prepositions (di/a/etc) go with which verbs. Useful website here.

Al mio fianco - at my side (lit.)

Although I have translated the expression literally, it would be better in English to translate it as “by my side”

Le persone sbagliate - the wrong people

Notice that these words are all in the feminine plural by the e at the end. The plural of persona is persone, hence le is the definite article, and the adjective (sbagliate) also needs to agree.

- “Now I am afraid of having the wrong people by my side”

I’m sitting in a broken down delivery truck, waiting for a tow, looking at pictures of some of my books, and wanting to be home

KANEKO’S CRIB NOTES XXV:THE HUMAN ELEMENT

Esoteric alchemical illustrations and ancient art aren’t the only inspiration for the ol’ creative spark here at KCC. Kaneko has been known to occasionally look to the wide world of contemporary pop-culture for inspiration, as is perhaps appropriate to the primarily modern setting of the series. With that in mind, it’s time to take account of some of the real (or nominally real) life figures that have left their mark on the vast design catalogue over the years.

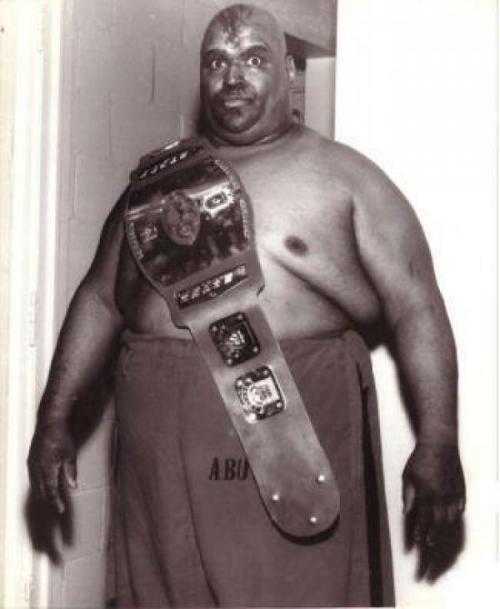

- BUTCHER:The mononymous “Butcher” offers a fairly literal take on the moniker of one-time wrestling extraordinaire Abdullah the Butcher, depicted here as a sort of crazed Messian executioner, title belt prominently displayed.

- NEMISSA:Nemissa is nothing short of a dead-ringer for Marianne Faithfull as she appears in the 1968 cult classic The Girl on a Motorcylce,sporting the iconic leather jacket/jumpsuit combo. This one is almost especially egregious save for the inclusion of some nominally stylish bell-bottoms on part of the former.

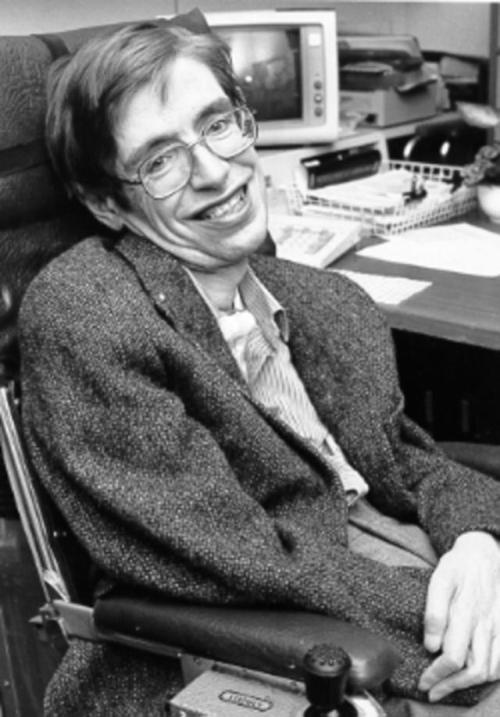

- STEPHEN:Resident science symbol and long-time demon fenangler Stephen is, of course, a supremely unsubtle nod to the acclaimed theoretical physicist of the same name. While the concept art itself doesn’t make for the best likeness, his in-game sprite is a bit more forward.

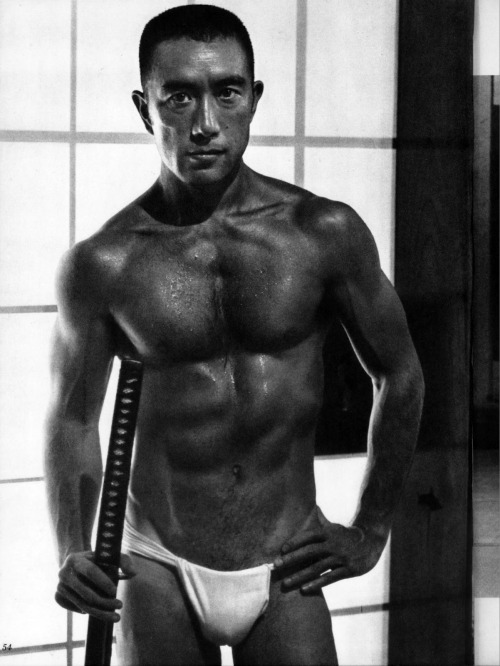

- GOTOU:The head honcho of the early Gaean faction is a none-too thinly veiled stand-in for renowned author and nationalist icon Yukio Mishima, both pictured above with rippling bod™ and tasteful fundoshi in tow. Like Stephen, his role in the narrative is at least partially informed by the character of his real-life counterpart.

- ALP:This iconic spirit of German folklore is largely inspired by the mascot of a short-lived ad campaign for Calpis Water that premiered during the early 90′s, starring actress Goto Kumiko as some sort of thirsty devil hell-bent on burglarizing parched civilians in search of the lightly flavored beverage, only to be foiled at the last minute by the various and cruel machinations of both fate and primitive green-screen technology.

Big props once again to dijeh for the scoop on Alp’s inspiration via his translation series and to turnipfritters for the hot tip on Nemissa! (KCN never forgets)

Post link