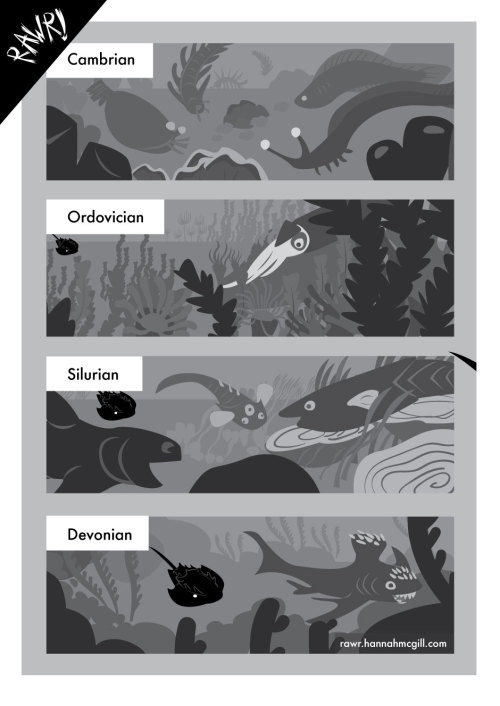

#ordovician

Baltica, by Maija Karala:

“I was asked to illustrate a spread of fossils and reconstructed animals from what the Baltic Sea was like in the Ordovician. They asked for colourful animals, and that’s what they got.

In the Ordovician, what is now Northern and Eastern Europe formed a small continent called Baltica, at the time located well south of the Equator. Much of the continent was covered in shallow seas, and there was a rich biodiversity of marine animals. Some of them have been preserved as fossils in Estonia, Åland islands and other places.

Made for Sieppo, a children’s magazine published by The Finnish Association for Nature Conservation.”

Post link

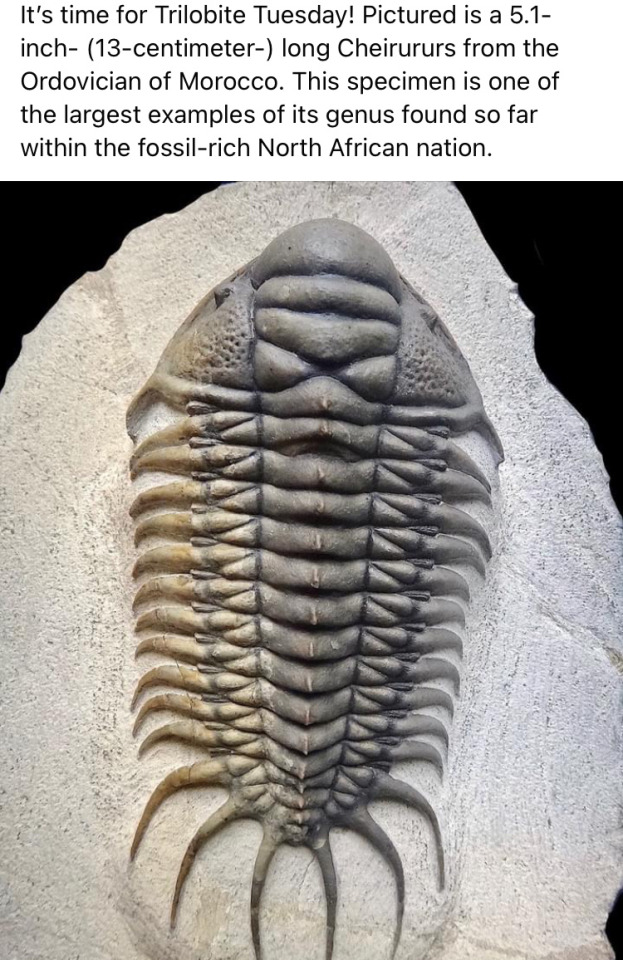

Happy Trilobite Tuesday from the American Museum of Natural History

I collected these crinoid stems in northern Kentucky a few weeks ago. And while they are aquatic invertebrates like everything else on this blog, they are 450 million years old… unlike everything else on this blog.

Adults in the class Crinoidea, or sea lilies, attach to the ocean bottom with these stems. The stems are quite common to find in high densities; sometimes they make up entire limestone beds. The arms and calyx of the lilies are much more difficult to find.

The fossil beds in Kentucky can be found along most road cuts and behind recent developments. It is solidly in the Ordovician period.

Post link

Changing it up briefly tonight! I collected these crinoid stems in northern Kentucky a few weeks ago. And while they are aquatic invertebrates like everything else on this blog, they are 450 million years old… unlike everything else on this blog.

Adults in the class Crinoidea, or sea lilies, attach to the ocean bottom with these stems. The stems are quite common to find in high densities; sometimes they make up entire limestone beds. The arms and calyx of the lilies are much more difficult to find.

The fossil beds in Kentucky can be found along most road cuts and behind recent developments. It is solidly in the Ordovician period.

Post link

Sacabambaspis – Late Ordovician (470-453 Ma)

Today we’re talking about something really cute. It’s an ancient, primitive fish with an adorable face. It’s Sacabambaspis!

What we’re looking at is an early jawless fish. Fish in the Ordivician period were small, simple little guys. Usually tubes with eyes and sometimes armor. Most of them didn’t even have fins, so a lot of them, including Sacabambaspis, look a lot like armor-plated tadpoles. It’s hard to imagine a world where fish don’t dominate the oceans, but that’s just how it was during the Ordovician. These guys, as well as their relatives, lived in the shadow of larger invertebrates, still enjoying the twilight of their rule that began during the Cambrian period.

Sacabambaspis was a bottom-dweller. Its mouth was pretty much just a circle in structure, but the inside was lined with bony plates that aided in suction feeding as it slurped bits of nutrients off the seafloor. Its eyes were square in the front of its head, giving it an adorable face. It’s like a little submarine, I just wanna hug it! Bony plates covered its gills and the front half of its body. There’s also evidence of a feature found in most modern fish called the lateral line. This is an organ system that lets fish sense the flow of water. There isn’t really an analogue in terrestrial vertebrates, but if I had to say one, it’s kind of like our sense of hearing. Kind of.

Although Agnatha (the technical name for jawless fishes) are the oldest group of fish, Sacabambaspis likely lived at the same time as early jawed fishes (Gnathostomata). This was still the primetime for jawless fishes, though. It would be a while before their jawed counterparts became more successful. So much more successful, in fact, that there are only two groups of agnathans alive today: lampreys and hagfish. Also, a fun fact about Gnathostomata is that the technical definition includes all vertebrates with jaws. So, you and I, and your dog, and my cat, are jawed fishes.

Don’t let all this talk of fish living in the shadows of bigger animals convince you that fish were underdogs or barely eking out their existence back then. It’s easy to try and fit the history of life into a sort of poetry, where the fish struggled along until given the chance to rise up and take over. That wasn’t really the case, though. Fish were thriving in the lower niches of the food web during this time. You wouldn’t call rodents underdogs today, just because none of them are apex predators in their ecosystems. Fish were similar; they were all over the place and lived all kinds of different lives. Considering what we know about the Ordivician fish, it’s not hard to see why they jumped at the opportunity to dominate the seas once the extinction event at the end of the period wiped out everything else. We like to think fish are dumb and primitive, but they have a spectacularly well-adapted body plan for aquatic life. They’re great at being animals, and I am ready to fight anyone who disagrees.

Post link

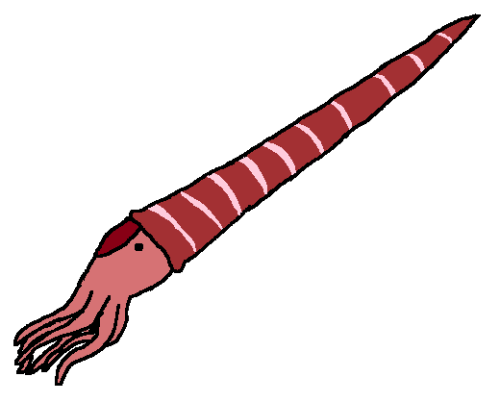

Endoceras – Middle-Late Ordovician (~470-445 ma)

For someone who loves invertebrates as much as I do, I don’t talk about them very much on this blog. So, today, I’m gonna return from hiatus with the second invertebrate featured on mspaleoart. Now presenting, Endoceras!

Endocerasremains have been found all over the United States, in states including Ohio, New York, Texas, and Montana. Remains have also been found at a single site in Poland. Make of that what you will.

This is the second oldest animal I’ve featured (Opabinia being the oldest), and that makes sense when you get into the particulars about this one. Let’s start with its phylogeny, or, its’ placement on the tree of life. If you know your marine invertebrates, you might notice it looks a bit like a long nautilus. And that’s basically what it is. It’s a member of the Nautilus family, and likely had many similar traits to our modern nautilus. There were some key differences, however. First and most obviously, the long, conical shell. Second was its size—Endoceras had an upper size limit of 13 feet (3.5 meters) in length.

So, the shell. We really don’t know what exactly to do about its shell. Why was it… like that? How did it affect how Endoceras went about its business? We have a few guesses. The classic portrait of Endoceras swimming like a modern squid is a bit controversial, since its shell was probably filled with air chambers for buoyancy, like its modern relative. It’s possible it floated vertically, and it’s also been proposed that it lived close to the bottom of the seafloor and ate smaller benthic animals. It was definitely slow because of that massive caboose; that much is pretty much certain.

And, you know what? Despite being slow and awkwardly-shaped, it was probably the apex predator in any ecosystem it was found in. How is that possible, exactly? Well, the most likely answer—as well as the answer to why it was able to get so damn big—is the lack of large fish. Fish evolved in the Cambrian, but really stayed in their lane and minded their own business until the Silurian—the period after Endoceras lived. Ordovician fish were tiny and jawless, hardly the dominators of ocean ecosystems they would eventually become. There were no sharks yet. Nothing was there to fill the niche of apex predator better than this big, clunky Star Destroyer of a cephalopod, so it ruled the scene for a while.

So, yeah, to give you an idea of how old Endoceras is, it’s older than fish jaws.

Endoceras may have been lucky (read: unlucky) enough to witness the Ordovician-Silurian extinction events. Collectively, this was the second mass extinction in earth’s history, and the second largest. Up to 70% of species on earth may have been wiped out at the end of the Ordovician period, and we don’t really know why. Some theories are:

- Big ol’ Glacier: At the end of the Ordovician, the ancient continent, Gondwana, drifted over the south pole and started to freeze over. This made the worldwide climate drier and colder, and screwed with ocean flow. Sea levels may have fluctuated and disrupted a lot of the ecosystems that flourished there before then.

- Volcanic eruptions: There isn’t too much to say about this one, other than that it’s the first thing a lot of people point to when presented with the question, “Why’d all these animals die?”

- Metal poisoning: There were a lot of toxic metals on the ocean floor during the Ordovician, and their breakdown might have poisoned the animals at lower levels of the food chain, which affected everything above them. Which might sound less devastating than the others, but it’s just as bad, or maybe even worse. I think Will and David over at the Common Descent Podcast put it best when they said that a mass extinction isn’t necessarily caused by a catastrophic event or natural disaster. It’s caused by the rug being pulled out from under an ecosystem, and the resulting destruction of ecological niches.

- GAMMA RAY BURST: This one is pretty buckwild. It’s been proposed that a gamma-ray burst from a nearby dying star might have kicked off the extinction event by destroying half the atmosphere’s ozone layer. There’s… really no evidence for it, despite Animal Armageddon implying that it’s more likely than it is.

But yeah, we really aren’t 100% sure, as is the case with most mass extinctions.

I saw Endoceras in a lot of paleoart as a kid. It was in a lot of books I read as one of the many unnamed, unusual creatures in the Paleozoic seas, pictured but not discussed. I just kind of knew it as that long nautilus for years, until I became more invested in invertebrate paleontology and the Paleozoic. The idea to draw this animal came when I was watching Animal Armageddon a few weeks ago. I don’t really recommend it, it’s a pretty bad documentary. It spends an entire episode discussing the Gamma Ray hypothesis for the O-S extinction, the only sorta-disclaimer that it’s basically unfounded being a throwaway line at the beginning saying, “Some scientists believe…” So yeah, it’s not the most informative.

Post link