#palaeoblr

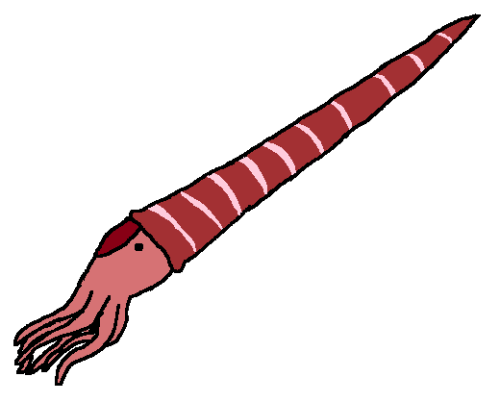

Endoceras – Middle-Late Ordovician (~470-445 ma)

For someone who loves invertebrates as much as I do, I don’t talk about them very much on this blog. So, today, I’m gonna return from hiatus with the second invertebrate featured on mspaleoart. Now presenting, Endoceras!

Endocerasremains have been found all over the United States, in states including Ohio, New York, Texas, and Montana. Remains have also been found at a single site in Poland. Make of that what you will.

This is the second oldest animal I’ve featured (Opabinia being the oldest), and that makes sense when you get into the particulars about this one. Let’s start with its phylogeny, or, its’ placement on the tree of life. If you know your marine invertebrates, you might notice it looks a bit like a long nautilus. And that’s basically what it is. It’s a member of the Nautilus family, and likely had many similar traits to our modern nautilus. There were some key differences, however. First and most obviously, the long, conical shell. Second was its size—Endoceras had an upper size limit of 13 feet (3.5 meters) in length.

So, the shell. We really don’t know what exactly to do about its shell. Why was it… like that? How did it affect how Endoceras went about its business? We have a few guesses. The classic portrait of Endoceras swimming like a modern squid is a bit controversial, since its shell was probably filled with air chambers for buoyancy, like its modern relative. It’s possible it floated vertically, and it’s also been proposed that it lived close to the bottom of the seafloor and ate smaller benthic animals. It was definitely slow because of that massive caboose; that much is pretty much certain.

And, you know what? Despite being slow and awkwardly-shaped, it was probably the apex predator in any ecosystem it was found in. How is that possible, exactly? Well, the most likely answer—as well as the answer to why it was able to get so damn big—is the lack of large fish. Fish evolved in the Cambrian, but really stayed in their lane and minded their own business until the Silurian—the period after Endoceras lived. Ordovician fish were tiny and jawless, hardly the dominators of ocean ecosystems they would eventually become. There were no sharks yet. Nothing was there to fill the niche of apex predator better than this big, clunky Star Destroyer of a cephalopod, so it ruled the scene for a while.

So, yeah, to give you an idea of how old Endoceras is, it’s older than fish jaws.

Endoceras may have been lucky (read: unlucky) enough to witness the Ordovician-Silurian extinction events. Collectively, this was the second mass extinction in earth’s history, and the second largest. Up to 70% of species on earth may have been wiped out at the end of the Ordovician period, and we don’t really know why. Some theories are:

- Big ol’ Glacier: At the end of the Ordovician, the ancient continent, Gondwana, drifted over the south pole and started to freeze over. This made the worldwide climate drier and colder, and screwed with ocean flow. Sea levels may have fluctuated and disrupted a lot of the ecosystems that flourished there before then.

- Volcanic eruptions: There isn’t too much to say about this one, other than that it’s the first thing a lot of people point to when presented with the question, “Why’d all these animals die?”

- Metal poisoning: There were a lot of toxic metals on the ocean floor during the Ordovician, and their breakdown might have poisoned the animals at lower levels of the food chain, which affected everything above them. Which might sound less devastating than the others, but it’s just as bad, or maybe even worse. I think Will and David over at the Common Descent Podcast put it best when they said that a mass extinction isn’t necessarily caused by a catastrophic event or natural disaster. It’s caused by the rug being pulled out from under an ecosystem, and the resulting destruction of ecological niches.

- GAMMA RAY BURST: This one is pretty buckwild. It’s been proposed that a gamma-ray burst from a nearby dying star might have kicked off the extinction event by destroying half the atmosphere’s ozone layer. There’s… really no evidence for it, despite Animal Armageddon implying that it’s more likely than it is.

But yeah, we really aren’t 100% sure, as is the case with most mass extinctions.

I saw Endoceras in a lot of paleoart as a kid. It was in a lot of books I read as one of the many unnamed, unusual creatures in the Paleozoic seas, pictured but not discussed. I just kind of knew it as that long nautilus for years, until I became more invested in invertebrate paleontology and the Paleozoic. The idea to draw this animal came when I was watching Animal Armageddon a few weeks ago. I don’t really recommend it, it’s a pretty bad documentary. It spends an entire episode discussing the Gamma Ray hypothesis for the O-S extinction, the only sorta-disclaimer that it’s basically unfounded being a throwaway line at the beginning saying, “Some scientists believe…” So yeah, it’s not the most informative.

Post link

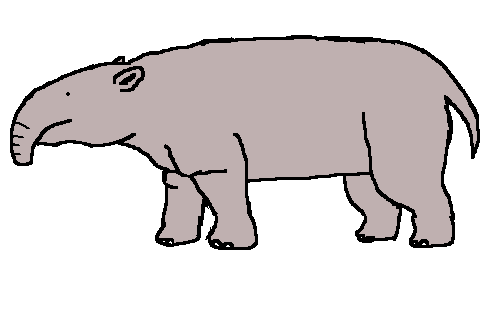

Moeritherium- Late Eocene (33-37 Ma)

Welcome back to the Mammal Zone™, we’re gonna be talking about a round friend named Moeritherium. It looks kind of like a hippo, kind of like a tapir, but isn’t closely related to either.

The Eocene was a very different time from now. The earth, almost done recovering from the Cretaceous extinction, was much warmer. Animals were starting to get big again, and many well-known branches of mammals started diverging, like whales and dogs. There was likely no ice at either pole, and much of the earth was covered in sprawling forests. Moeritheriumlazed around in rivers and lakes in Egypt, feeding on soft underwater plants, if its teeth are to be believed. And teeth can tell us a lot.

Moeritheriumis an early member of the order Proboscidea, which is represented today only by elephants.It most likely had a short trunk, probably used for gripping food, not for snorkeling, sadly. It had two elongated incisors in its upper jaw, which betray its cousinship with elephants. It was only a little over 2 feet tall at the shoulder, too. Isn’t it cute?

Even though it’s commonly used as an example of the first elephant, it wasn’t directly ancestral to elephants, probably belonging to a branch of proboscids that died out long ago. Even though they have a definite resemblance, Moeritherium’sshort legs and hippo-like lifestyle probably point to a group of animals that evolved in a very different direction. In fact, they lived at roughly the same time as a more likely candidate for elephant ancestry, Phiomia.

Moeritheriumwas featured in the second episode of BBC’s Walking with Beasts, where a group of them mostly just hangs out and eats. I liked Moeritheriumas a kid because I thought it looked funny. Of course, I was told that it was the precursor to elephants (until I went to Christian school and was told that nothing was the precursor to anything). No matter how closely related to elephants it is, I just think it’s neat.

Post link

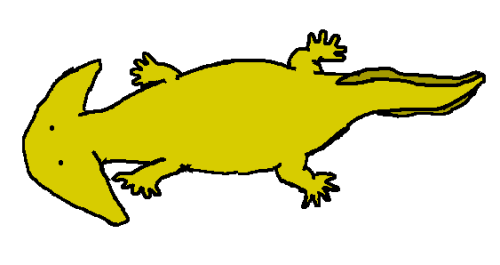

Diplocaulus- Early-Late Permian (~270-245 ma*)

Our second Permian animal, and our first definite-absolute amphibian, is Diplocaulus, a 3-foot long predator from Texas, and maybe Morocco. It’s… super weird and I feel very strongly about it.

For the most part, Diplocauluslooked and acted pretty much like a Giant Salamander. It had a sprawling, four-legged gait. It spent most of its time in the water hunting fish. It lived and reproduced in burrows near lakes or other bodies of fresh water. It weighed about 5-10 pounds, as much as a cat.

Anyway, let’s talk about that head. It’s shaped like a boomerang because… It just happened like that? The problem with extinct animals is that the farther back in the fossil record you go, the less information we have on them. But no, everything under natural selection happens for a reason, even things as ridiculous as this. Maybe it served as a hydrofoil, letting it swim faster. Another theory is that it was shaped so awkwardly so nothing could swallow it. I like that one. It was definitely hard to lug around on land, though. They can’t all be winners.

We also have fossil evidence that Dimetrodonwas a frequent predator of this soggy boy. One set of remains looks like a crime scene, where a Dimetrodondug up a burrow and ate some young Diplocaulus. This maybe says that Diplocaulustook care of its young beyond squeezing them out and walking away, but maybe it’s best not to read too much into it. Maybe they all just holed up in the ground together during the dry season.

Diplocaulusis unique within its group, the Lepospondyls. Lepospondyls were one of the oldest groups of amphibians, and were characterized by simple backbones, which were basically just the primitive notochord wrapped in bone. Diplocaulusis one of the largest in that class, as well as the youngest, living well into the late Permian. It’s also the only one we know of that looked like a banana. The placing of Lepospondyli is a little up in the air. We’re not sure if they’re the early ancestors of modern amphibians, or if they’re directly descended from the earliest land vertebrates, or what.

For some reason, it’s been the subject of a number of hoaxes claiming it’s still alive. Seriously, google ‘diplocaulus real’ and you’ll find so many pictures and videos of people trying to say they saw one. I don’t know why this keeps happening to Diplocaulus, of all animals, but it does. Maybe because it’s small and easy to fake? It’s also appeared in pop culture a few times, which is kinda strange for something of this sort. It’s in ARK: Survival Evolved (Basically in name only. It’s REALLY big and REALLY angry-looking), as well as a few Jurassic Park games (again in name only). It also shows up briefly in the anime Neon Genesis Evangelion, which I only mention because I like NGE. It’s only there for like, a second in the last episode. I can’t offer any further context, because it’s the last episode of Neon Genesis Evangelion.

Diplocaulushas always had a special place in my heart. When I was a kid, my grandparents gave me a bunch of books about Dinosaurs that belonged to my dad when he was young. One of them was titled Prehistoric Monsters did the Strangest Things. It’s from 1974, and the cover literally has a bunch of sauropods standing in a lake munching on seaweed, so that should tell you everything you need to know about the accuracy of the book. I still ate that shit up. Diplocaulusis the animal they use to talk about the transition from sea to land (on this spread right here). I stole the color scheme, because in my head it’s always been yellow.

*There are no exact dates for Diplocaulus’ span of existence, so I snowballed it from the beginning of the Permian to a bit before the Great Dying. If I’m wrong, and there are dates for it, please let me know!

Post link

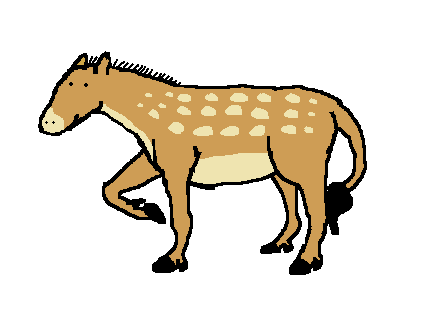

Mesohippus- Middle Eocene-Early Oligocene (37-32 Ma)

Horses, the vigilant eyes of an angry God. I think most people are familiar with horses and their journey to becoming our third best friend, and Mesohippus is plucked right from the earlier acts of that transformation.

Mesohippuslived, along with many horse ancestors, in North America. It was about two feet tall. It was still far from becoming a grassland animal. Its teeth were still designed for eating twigs and fruit. But, it shows a few important steps towards modern horse anatomy. Firstly, its snout was becoming more narrow. Its brain was larger than its forebears too, and was probably very similar to a modern horse’s. It was leaner, starting to develop that aerodynamic horse skeleton.

Its legs are longer than those of of its ancestors, and it now has three toes instead of four, with only the middle toe bearing the weight of its body. Eventually, that middle toe would go on to be its only toe, the ‘fingernail’ of which becoming the hoof. The genes for extra toes still exist in horses, and sometimes they’re born with an extra toe that looks pretty similar to Mesohippus’.

This was probably around the point when horses started running as a survival tactic. Eocene North America was also home to Hyaenodonts and Nimravids, which probably ate Mesohippusif they could catch it. Not to mention various species of flightless bird (Gastornis was a herbivore, as we talked about before, but there were other flightless birds in the early Cenozoic that absolutely ate horses). Obviously, this pressure from fast predators was helpful when humans needed to go places faster.

I wasn’t sure which horse I wanted to talk about today (because for some reason, I said I’d do a horse). I went through a few. I didn’t want to do EohippusorPropalaeotherium, because I don’t think there’s anything new I could say about them. So I went forward in time a little bit and got to know Mesohippus. It’s a neat little animal, and an interesting transition between the short, chubby horses of the early Eocene and the towering, omnipotent grass annihilators we know and righteously fear today.

Post link

Eoraptor

Dilophosaurus

Merry Christmas

Stegouros

Tarchia tumanovae

Mussaurus

Pentaceratops

Baryonyx

Giganotosaurus

Daspletosaurus

Stygimoloch

Saurolophus

Parksosaurus

Deinocheirus

Therizinosaurus

Hesperornis