#oligocene

Obdurodon

Skull on display at the American Museum of Natural History, NYC

Reconstruction by Anne Musser

When: Late Oligocene to Miocene (~25 to 12 Million years ago)

Where: Australia

What: Obdurodon is a fossil platypus, as is fairly obvious from a look at its skull. Though upon closer inspection there are some very important differences; Obdurodon had a larger bill than the living platypus and retained teeth as an adult. Modern adult platypus are toothless, shedding all their teeth as juveniles. These teeth are important as they help us place monotremes (platypus and the echidna are the modern representatives) into the mammal family tree. It is now the consensus that marsupials and placentals are more closely related to one another than either is to the monotremes, but there are a great deal of extinct groups of mammals that may fall between therians and the monotremes - such as the multituberculates. Fossils such as Obdurodon which are most assuredly related to modern monotremes, but preserve more primitive features, are critically important for this phylogenetic issue. So then why is it still an issue? All we have of Obdurodon is a skull, despite the full body reconstruction above, and while there are fossils of even older monotremes they are even more scrappy - just isolated teeth or jaw fragments (that still enjoy full body reconstructions…).

How did Obdurodon live compared to the modern platypus? Well, the living form uses its bill in the water to help it sense prey, and as Obdurodon had an even larger bill, it seem likely it also was aquatic, though without a postcranial skeleton it is unknown if it had the same swimming and digging adaptions seen in its extant relatives.

Post link

Palaeolagus

When: Late Eocene to Mid Oligocene (~38 to 27 million years ago)

Where: North America

What:Palaeolagus is a fossil lagomorph. Lagomorpha is an order of mammals, that contains rabbits, hares, and pikas. Within the bunny-order rabbits and hares are more closely related to either other than either is to the pikas. If you are not familiar with pikas go check out some pictures! They are really cute little guys that resemble guinea pigs more than they do rabbits, but they are most assuredly lagomorphs. Palaeolagus falls outside all living lagomorphs in their evolutionary lineage. It can be thought of as representative of the common ancestor of all living lagomorphs.

Palaeolagus lived in North America in the late Eocene, after the dense forests had left and the grasslands of the plains started to expand. This 10 inch (~25 cm) long herbivore spread throughout the continent during the Oligocene as the grasslands grew. Palaeolagus could not hop, its hind legs show none of the features that make a hopping locomotion style possible in living rabbits.This ancient bunny is known from a large amount of fossil specimens, some of which are almost complete skeletons, but most are fragmentary pieces of bone or teeth. Most of these Palaeolagus specimens likely met their end as the lunch of one of the many predators roaming the grass lands of prehistoric North America.

Post link

Metamynodon, Zdeněk Burian, 1969

Metamynodon’s day is spent in leisure. Wallowing, feeding, sighing. A breeze rattles the reeds and chills the spots where its hide is wet with mud, so it sinks deeper, hides from the wind in the bog, and lets the mud squish between its toes and clog its armpits and nether regions. It breaks wind, flips its tail, watches the water slosh over the mud, its reflection rolling on ripples more active than the beast itself. Life could no be better.

Post link

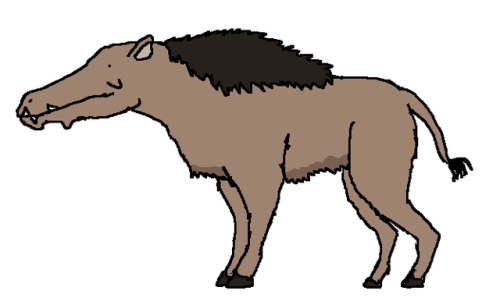

Daeodon – Late Oligocene-Early Miocene (29-19 Ma)

As I said last time we went to Mammal Junction, a lot of mammals from the prehistoric Cenozoic are similar to mammals we have now, or look kind of like a generic mammal. Some of them, though, weren’t. Some were absolutely positively bizarre. Let’s talk about one.

This ugly motherfucker is named Daeodon, and lived in North America during the Paleogene-Neogene divide. Daeodon—and other entelodonts, by extension—is essentially what it looks like. It’s a carnivorous ungulate, or, hoofed mammal. No surprises here, other than the fact it existed. Today, the only ungulates who eat meat are whales1. Ungulates make up most of the large land mammals today, and they’re all big grazers. Daeodon and its cousins, however, were apex predators.

If you’ve seen Walking with Beasts, Daeodon might look familiar to you. A similar animal appears in the third episode, “Land of Giants,” called an “entelodont.” That one lived in central Asia and probably belonged the genus Entelodon. If you’ve seen the documentary, you certainly remember maybe the most gruesome scene in the entire franchise, where a territorial fight between two of them leads to one’s face being fucked right up. Even as a violence-loving kid that one kind of made me shudder.

But even though Walking with tends to sensationalize its animals, that wasn’t really the case this time. They were probably a lot like that. Aggressive, terrifying, and ugly as hell. I wanted to give them a little more fur, though, since I personally don’t believe they were naked like a domestic pig. They’ve been nicknamed “Hell pigs” or “Terminator pigs” and I find it hard to disagree.

They had big-ass heads and powerful jaws with pairs of huge canines and incisors, along with batteries of tough, blunt molars. This mixture of teeth is, weird as it probably sounds, sorta convergent with ours. Sharp front teeth and dull, rounded teeth in the back? These were the teeth of an omnivore. They fed themselves with a mix of scavenging and active hunting, and probably rounded out their diet with roots and tubers, an echo of their relationship with other hooved animals. They’re like a concept for a horror movie character. It’s like Kujo for pigs, I think. I don’t know much about Kujo other than the fact that Stephen King was inebriated when he wrote it and doesn’t even remember doing so.

It’s important to mention that they weren’t actually pigs, although we used to think some of them were. They’re the weird cousin pigs don’t talk about. Paleontologists like to disagree on how closely they were related to pigs and other artiodactyls (even-toed ungulates). I did a lot of digging to see where they might fall, and the general consensus looks like “somewhere around hippos and whales2.”

More about this genus specifically, Daeodon was the largest member of the entelodont family, being a bit taller than the average grown man. I am really glad I don’t live alongside these things. One specimen was originally named Dinohyus, which means “terrible pig.” It’s thought that Daeodon, more than other entelodonts, was mostly a scavenger. It followed other carnivores around and waited for them to kill something, then got in there and screamed at them until they ran away. These were huge animals with mouths full of sharp teeth; it probably wasn’t too hard for them to terrify their fellow meatboys.

Daeodon is also interesting because it’s kind of a tangle in the entelodont family tree. First of all: entelodonts are found pretty evenly in Eurasia and North America. So, there’s a cousin of Daeodon who lived in the same region of North America, a few million years earlier, called Archaeotherium. I actually almost talked about that one today instead. The obvious conclusion there is that Daeodon is descended from Archaeotherium, right? And that was the idea for a long time. But, looking closer, we found that it looks more like its cousins on the other side of the Pacific. It might be descended from an immigrant population of entelodonts who crossed over from Asia. Wack.

This leads to some questions, like, were the entelodonts in America just worse at being entelodonts? Did these guys come over the land bridge and just outcompete them? It’s really hard to say, since most animals aren’t fossilized and it’s totally possible they coexisted with native entelodonts and we just haven’t found them. Of course, they might also just be descended from American entelodonts and happened to develop convergent traits with their cousins across the pond. Listen, this science is a total disaster sometimes. We’re doing the best we can with piles of bones we find in the dirt.

So, yeah, that’s Daeodon, the murder “pig.” The Cenozoic is still full of surprises for us. A lot of the animals that didn’t survive to modern times are absolutely buckwild, and if this one doesn’t prove that, I’ll need to try harder. I mean, even if it does convince you, there’s still some weird shit out there that I’d love to cover. And that’s why I’m here!

P.S. If you haven’t seen Walking with Beasts, I highly recommend it. It’s the passion project of the Walking with team, and probably the most accurate installment of the three.

1Whales evolved from ungulates, and so are considered members of that group even though they have no gotdamn legs

2If any of my readers know more about the relationship between entelodonts and other artiodactyls, please let me know. I’m not certain that I’m right on this and I’d love clarification

Post link

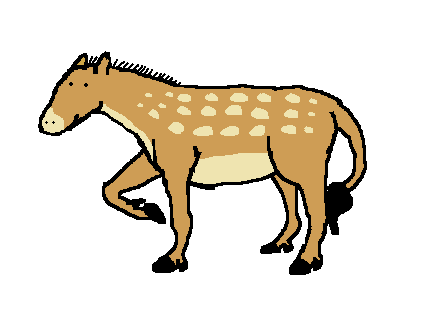

Mesohippus- Middle Eocene-Early Oligocene (37-32 Ma)

Horses, the vigilant eyes of an angry God. I think most people are familiar with horses and their journey to becoming our third best friend, and Mesohippus is plucked right from the earlier acts of that transformation.

Mesohippuslived, along with many horse ancestors, in North America. It was about two feet tall. It was still far from becoming a grassland animal. Its teeth were still designed for eating twigs and fruit. But, it shows a few important steps towards modern horse anatomy. Firstly, its snout was becoming more narrow. Its brain was larger than its forebears too, and was probably very similar to a modern horse’s. It was leaner, starting to develop that aerodynamic horse skeleton.

Its legs are longer than those of of its ancestors, and it now has three toes instead of four, with only the middle toe bearing the weight of its body. Eventually, that middle toe would go on to be its only toe, the ‘fingernail’ of which becoming the hoof. The genes for extra toes still exist in horses, and sometimes they’re born with an extra toe that looks pretty similar to Mesohippus’.

This was probably around the point when horses started running as a survival tactic. Eocene North America was also home to Hyaenodonts and Nimravids, which probably ate Mesohippusif they could catch it. Not to mention various species of flightless bird (Gastornis was a herbivore, as we talked about before, but there were other flightless birds in the early Cenozoic that absolutely ate horses). Obviously, this pressure from fast predators was helpful when humans needed to go places faster.

I wasn’t sure which horse I wanted to talk about today (because for some reason, I said I’d do a horse). I went through a few. I didn’t want to do EohippusorPropalaeotherium, because I don’t think there’s anything new I could say about them. So I went forward in time a little bit and got to know Mesohippus. It’s a neat little animal, and an interesting transition between the short, chubby horses of the early Eocene and the towering, omnipotent grass annihilators we know and righteously fear today.

Post link

Chalicotherium – Late Oligocene-Early Pliocene (28-3 Ma)

You know what? I’m bored of prehistoric animals. Starting today, I’m just gonna pull a Jurassic World and start making shit up. Here’s my OC, it’s a gorilla horse and its name is Steven.

Just kidding, this is a real animal. It’s not a particularly obscure one, so I probably didn’t fool a lot of you. Also, I’m bad at lying so that doesn’t help my case.

So, continuing with the theme of weird-ass mammals from the Cenozoic, we’re talking about Chalicotherium. What’s the deal with Chalicotherium? Every detail about it only makes it weirder. It was a knuckle-walking herbivore from Eurasia, with the head of a horse. Its forelimbs were elongated and tipped with long claws. Its hind limbs were shorter, and it probably spend a long time sitting back on them. Despite this, Chalicotherium was a peaceful animal. It used its claws to pull branches down and munch on soft vegetation. It probably walked on its knuckles to avoid wearing the claws down. Juveniles had incisors and canine teeth at the front of their jaw, like we do, but as they matured, the teeth fell out and weren’t replaced, leaving only the molars. When they were younger and smaller, they probably only had access to the tougher plants close to the ground. But as they matured and could reach higher plants, they no longer needed teeth for cutting and stripping leaves. Adult Chalicotherium were probably picky eaters. And since they were the tallest animals in their ecosystems, they could afford to be. As far as we know, there weren’t any other animals gunning for that good, good vegetation up there. Or at least, not animals that could reach it.

Chalicotherium was an odd-toed ungulate, and its closest living cousins are tapirs, horses, and rhinos. The Chalicothere family was long-lived, first evolving from small woodland types in the Eocene. Their ancestors probably looked a lot like early horses, chubby little animals with short toes. As grasslands became increasingly prevalent in the Cenozoic, Chalicotheres diverged into two groups: One that stayed in the woodlands and took care of business as usual, and another group that took advantage of this strange new ecosystem and populated the grasslands. Chalicotherium belonged to the latter. The family survived until surprisingly recently, with the most recent member living until about 700,000 years ago.

Depending on who you ask, Chalicotherium might even still be hanging around (DISCLAIMER: Almost certainly not). A Kenyan cryptid called the Nandi Bear has been speculated by some to be a Chalicothere, given the description of an animal with a sloped back and sharp claws. Although, the Nandi Bear is supposed to be a carnivore, so that doesn’t really vibe with our friend the Chalicotherium. According to local tradition, the Nandi Bear eats only the brains of its victims, and that’s definitely not what this animal was about. Chalicotherium just wanted to wander around and eat leaves. It wasn’t a violent animal. So yeah, it’s not true, but it’s fun to talk about.

I’ve wanted to draw Chalicotherium for a while. It’s such a bizarre animal, and I love the detail with which we can analyze the mammals of the Cenozoic. I first heard about this family from Walking with Beasts. I’ve kind of inadvertently covered most of the animals from “Land of Giants”. The first mammal I talked about was the star of that episode, Paraceratherium, and the last Cenozoic animal I discussed was an Entelodont. Oh well. I just think they’re neat.

Post link