#paleogene

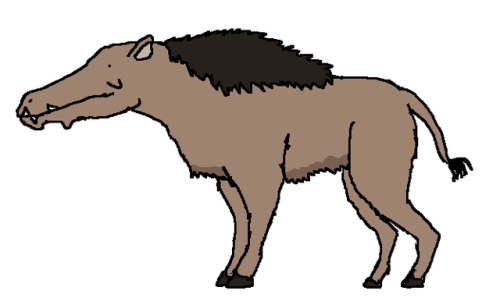

Daeodon – Late Oligocene-Early Miocene (29-19 Ma)

As I said last time we went to Mammal Junction, a lot of mammals from the prehistoric Cenozoic are similar to mammals we have now, or look kind of like a generic mammal. Some of them, though, weren’t. Some were absolutely positively bizarre. Let’s talk about one.

This ugly motherfucker is named Daeodon, and lived in North America during the Paleogene-Neogene divide. Daeodon—and other entelodonts, by extension—is essentially what it looks like. It’s a carnivorous ungulate, or, hoofed mammal. No surprises here, other than the fact it existed. Today, the only ungulates who eat meat are whales1. Ungulates make up most of the large land mammals today, and they’re all big grazers. Daeodon and its cousins, however, were apex predators.

If you’ve seen Walking with Beasts, Daeodon might look familiar to you. A similar animal appears in the third episode, “Land of Giants,” called an “entelodont.” That one lived in central Asia and probably belonged the genus Entelodon. If you’ve seen the documentary, you certainly remember maybe the most gruesome scene in the entire franchise, where a territorial fight between two of them leads to one’s face being fucked right up. Even as a violence-loving kid that one kind of made me shudder.

But even though Walking with tends to sensationalize its animals, that wasn’t really the case this time. They were probably a lot like that. Aggressive, terrifying, and ugly as hell. I wanted to give them a little more fur, though, since I personally don’t believe they were naked like a domestic pig. They’ve been nicknamed “Hell pigs” or “Terminator pigs” and I find it hard to disagree.

They had big-ass heads and powerful jaws with pairs of huge canines and incisors, along with batteries of tough, blunt molars. This mixture of teeth is, weird as it probably sounds, sorta convergent with ours. Sharp front teeth and dull, rounded teeth in the back? These were the teeth of an omnivore. They fed themselves with a mix of scavenging and active hunting, and probably rounded out their diet with roots and tubers, an echo of their relationship with other hooved animals. They’re like a concept for a horror movie character. It’s like Kujo for pigs, I think. I don’t know much about Kujo other than the fact that Stephen King was inebriated when he wrote it and doesn’t even remember doing so.

It’s important to mention that they weren’t actually pigs, although we used to think some of them were. They’re the weird cousin pigs don’t talk about. Paleontologists like to disagree on how closely they were related to pigs and other artiodactyls (even-toed ungulates). I did a lot of digging to see where they might fall, and the general consensus looks like “somewhere around hippos and whales2.”

More about this genus specifically, Daeodon was the largest member of the entelodont family, being a bit taller than the average grown man. I am really glad I don’t live alongside these things. One specimen was originally named Dinohyus, which means “terrible pig.” It’s thought that Daeodon, more than other entelodonts, was mostly a scavenger. It followed other carnivores around and waited for them to kill something, then got in there and screamed at them until they ran away. These were huge animals with mouths full of sharp teeth; it probably wasn’t too hard for them to terrify their fellow meatboys.

Daeodon is also interesting because it’s kind of a tangle in the entelodont family tree. First of all: entelodonts are found pretty evenly in Eurasia and North America. So, there’s a cousin of Daeodon who lived in the same region of North America, a few million years earlier, called Archaeotherium. I actually almost talked about that one today instead. The obvious conclusion there is that Daeodon is descended from Archaeotherium, right? And that was the idea for a long time. But, looking closer, we found that it looks more like its cousins on the other side of the Pacific. It might be descended from an immigrant population of entelodonts who crossed over from Asia. Wack.

This leads to some questions, like, were the entelodonts in America just worse at being entelodonts? Did these guys come over the land bridge and just outcompete them? It’s really hard to say, since most animals aren’t fossilized and it’s totally possible they coexisted with native entelodonts and we just haven’t found them. Of course, they might also just be descended from American entelodonts and happened to develop convergent traits with their cousins across the pond. Listen, this science is a total disaster sometimes. We’re doing the best we can with piles of bones we find in the dirt.

So, yeah, that’s Daeodon, the murder “pig.” The Cenozoic is still full of surprises for us. A lot of the animals that didn’t survive to modern times are absolutely buckwild, and if this one doesn’t prove that, I’ll need to try harder. I mean, even if it does convince you, there’s still some weird shit out there that I’d love to cover. And that’s why I’m here!

P.S. If you haven’t seen Walking with Beasts, I highly recommend it. It’s the passion project of the Walking with team, and probably the most accurate installment of the three.

1Whales evolved from ungulates, and so are considered members of that group even though they have no gotdamn legs

2If any of my readers know more about the relationship between entelodonts and other artiodactyls, please let me know. I’m not certain that I’m right on this and I’d love clarification

Post link

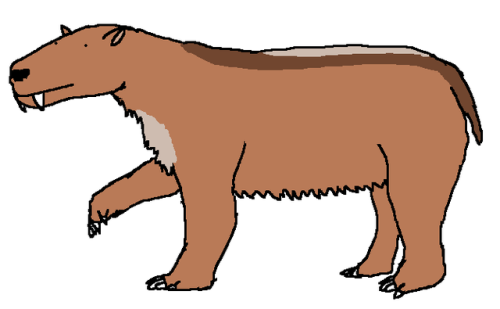

Titanoides – Late Paleocene (59-56 Ma)

Our record of the Cenozoic era is very rich. Super rich. With a few exceptions, we understand the ancestry of not only most living mammals, but most living vertebrates. A lot of this knowledge goes unnoticed, though. Maybe because so many of these animals are so similar to the stuff we have now. I will admit that the Cenozoic is the era I know the least about. Part of the idea behind this blog is to educate myself, so we’re going to talk about mammals I had no idea existed until about a week ago.

Titanoidesis an old mammal from North Dakota. It lived just in the wake of the K-Pg extinction event, which, if you don’t know, was the one that hit the earth so hard that non-avian dinosaurs died out and the Mesozoic era was cancelled. Life is super tenacious, though. Barely 5 million years after the extinction event, mammals and birds had already filled the niches left by larger animals.

Let’s take a quick look at its anatomy. It’s a squat and stocky animal, about 10 ft (3.5 m) long. It probably weighed over 300 lbs (136 kg).* Titanoides was the largest mammal in its habitat, and one of the largest animals of its day. Mammals are set apart from their kin by their diverse teeth, and this one is no exception. It had two enlarged canine tusks. It was a quadruped with big, clawed paws. You might think this animal was a predator, but it was actually an herbivore. Titanoides’ home state of North Dakota was, believe it or not, a dense tropical swamp during the Paleocene, and our friend Titanoides used its tusks to uproot plants and tubers, or to strip bark from trees. It was definitely no pushover, though. The tusks, combined with its claws and beefy body, meant it was absolutely capable of squaring up with anything trying to eat it. It seems a bit like the Paleocene equivalent of a hippo, although we don’t have anything to suggest it was aquatic. It’s similar in that it falls into the “big plant munchers that will fuck you up” category.

Here, follow me to the Taxonomy Zone real quick. Titanoides is what’s called a pantodont.

“Hey, Dylan, what the hell is a Pantodont?”

Thank you for asking! I didn’t really know either. Pantodonts are an extinct suborder (or order, who knows?) of mammals that had a short burst of existence during the beginning of the Paleogene period. They were some of the first large mammals, and to find how they relate to animals alive today, we have to dig a little. They have no living descendants. They fall under the order Cimolesta, which is also extinct. Buuuut, certain members of Cimolesta may have been ancestors to the currently-living order Carnivora (pretty much every carnivorous mammal except whales). So, to put it in terms that make sense, pantodonts are distant great-great-great-great cousins of our modern meat-eating mammals. Here’s a (really simplified) chart:

So, yeah, Titanoides has deep roots. It is deep roots, really. But it’s important, because it’s one of the first big grazing animals in the asteroid’s wake. It’s a sign of things to come for mammals, really, if you’re looking back on the history of life on earth like most of us are. But in the Paleocene, it was just an animal. It’s like looking back at today from 30 million years in the future. Elephants and giraffes, and maybe even humans, would seem like halfway points in a timeline of our descendants’ evolution.

*Weight is really hard to guess for prehistoric animals, especially those we only know from skeletons. We don’t know how much meat was on those bones.

Post link

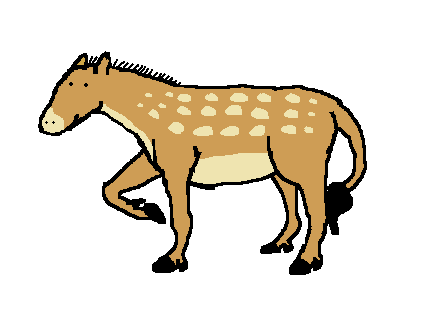

Mesohippus- Middle Eocene-Early Oligocene (37-32 Ma)

Horses, the vigilant eyes of an angry God. I think most people are familiar with horses and their journey to becoming our third best friend, and Mesohippus is plucked right from the earlier acts of that transformation.

Mesohippuslived, along with many horse ancestors, in North America. It was about two feet tall. It was still far from becoming a grassland animal. Its teeth were still designed for eating twigs and fruit. But, it shows a few important steps towards modern horse anatomy. Firstly, its snout was becoming more narrow. Its brain was larger than its forebears too, and was probably very similar to a modern horse’s. It was leaner, starting to develop that aerodynamic horse skeleton.

Its legs are longer than those of of its ancestors, and it now has three toes instead of four, with only the middle toe bearing the weight of its body. Eventually, that middle toe would go on to be its only toe, the ‘fingernail’ of which becoming the hoof. The genes for extra toes still exist in horses, and sometimes they’re born with an extra toe that looks pretty similar to Mesohippus’.

This was probably around the point when horses started running as a survival tactic. Eocene North America was also home to Hyaenodonts and Nimravids, which probably ate Mesohippusif they could catch it. Not to mention various species of flightless bird (Gastornis was a herbivore, as we talked about before, but there were other flightless birds in the early Cenozoic that absolutely ate horses). Obviously, this pressure from fast predators was helpful when humans needed to go places faster.

I wasn’t sure which horse I wanted to talk about today (because for some reason, I said I’d do a horse). I went through a few. I didn’t want to do EohippusorPropalaeotherium, because I don’t think there’s anything new I could say about them. So I went forward in time a little bit and got to know Mesohippus. It’s a neat little animal, and an interesting transition between the short, chubby horses of the early Eocene and the towering, omnipotent grass annihilators we know and righteously fear today.

Post link

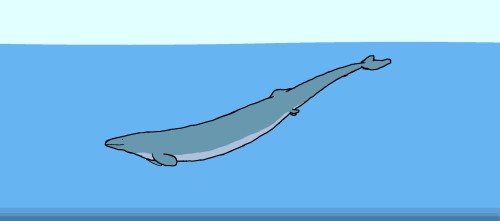

Basilosaurus cetoides

Late Eocene (41-34 Ma)

Bluuughhhhhhh. I forgot the clocks were going to move forward last weekend, and my schedule is completely off-kilter. But after slamming most of a big cup of coffee, I’m here to talk about a really cool whale. The Eocene was a great time to be a mammal. After taking their first shaky steps into the limelight during the Paleocene, mammals took over the world in the Eocene. Whales were among the most immediately successful groups, and Basilosaurus was one of the earliest whales fully adapted for marine life. It had a fusiform body and a powerful fluked tail, with its forelimbs adapted into flippers. They ranged in size from 15-20 meters, making them not only one of the earliest large whales, but possibly the largest animal in the Paleogene period.

It’s no secret that I love taxonomy, so let’s talk about it!

There are two species of Basilosaurus: The type species, B. cetoides and the slightly smaller B. isis. ‘Basilosaurus’ means ‘King Lizard,’ which is weird because, you know, it’s a whale. It’s called that because its discoverers thought it was some kind of sea serpent thanks to its weird body proportions. After the realization it was a whale, the name Zeuglodon was suggested as a replacement. However, since Basilosaurus was the first name given, it had priority, and Zeuglodonbecame a junior synonym. It gets wackier. Another junior synonym is Alabamornis.This means ‘bird from Alabama,’ and was given to what was thought to be a big bird’s shoulder bone in 1906, but was actually a pelvis of Basilosaurus. And on the less scientific side of things, in 1845, Dr. Albert Koch unveiled the skeleton of a giant sea serpent he called “Hydrarchos,” which would have been really cool if it wasn’t really fake. It was probably two Basilosaurusskeletons stuck together, but we don’t know for certain because it was destroyed in 1871 by the great Chicago fire.

Despite looking like a modern whale in many respects, Basilosaurus was still weird. Compared to modern predatory whales, it has a proportionally longer body and neck. Its head was smaller, with no room for a melon (the adorable name for the hearing organ toothed whales have in their foreheads). It had a smaller brain too, and probably wasn’t as social or intelligent as say, an orca. Its flippers also had a functioning elbow joint, like sea lions. It was probably best at swimming in two dimensions near the water’s surface, rather than diving.

Perhaps the strangest thing, though, is its pair of tiny hind limbs and pelvis disconnected from the vertebral column. Some whales today have tiny, vestigial hind limbs, but they’re reduced to a few useless bones hidden beneath the skin. Basilosaurus’back legs were recognizable as such, and were used for… something. Maybe holding onto each other while mating, almost certainly not for biking.

This animal was widespread throughout the Tethys sea, the ancient waterway between Gondwana and Laurasia in the Mesozoic. As Africa and Eurasia moved toward each other, it was beginning to split in the Eocene, but it still covered swaths of land in shallow, warm sea. The two species of Basilosaurus have different teeth, and probably fed on different prey. B. cetoides typically ate large fish and sharks. B. isis, though, is known to eat Dorudon, a smaller basilosaurid whale. Specimens of Dorudon have been found with bite marks in the skull, attributed to Basilosaurus, and the damage done to the skeletons around it suggest B. isis hunted by delivering a fatal wound to the head before tearing the body apart with its jaws, which sounds metal as hell.

Basilosaurus has always been a favorite mammal of mine. It has a certain elegance and beauty I’ve always admired, the first of the cetacean giants. Although I’m not a particularly religious or spiritual person, there’s something magical about seeing such a huge animal swimming in open waters. I hope I captured some that mystified feeling with this drawing. I first saw Basilosaurusin the second episode of Walking with Beasts, wherein a pregnant B. isis has to find food at the beginning of a climate crisis. WWBconstitutes a good 70% of my Cenozoic knowledge. It probably won’t be long before I’ve drawn every mammal featured in it, and I swear I’m not doing that on purpose. Mammals aren’t really my strong suit, especially not whales, but I had a lot of fun drawing this. And part of the point of this blog is to teach myself about groups I otherwise don’t really study, so I guess you could say I did a good job of that.

SOURCES

Riley Black, 2009 – The Rise and Fall of Alabamornis

Gingerich, 1998 – Paleobiological Perspectives on Mesonychia, Archaeoceti, and the Origin of Whales

Voss, et al. 2019 – Stomach contents of the archaeocete Basilosaurus isis

******************************************************************************

Buy me a Ko-fi, if you’d like!

Post link

Chalicotherium – Late Oligocene-Early Pliocene (28-3 Ma)

You know what? I’m bored of prehistoric animals. Starting today, I’m just gonna pull a Jurassic World and start making shit up. Here’s my OC, it’s a gorilla horse and its name is Steven.

Just kidding, this is a real animal. It’s not a particularly obscure one, so I probably didn’t fool a lot of you. Also, I’m bad at lying so that doesn’t help my case.

So, continuing with the theme of weird-ass mammals from the Cenozoic, we’re talking about Chalicotherium. What’s the deal with Chalicotherium? Every detail about it only makes it weirder. It was a knuckle-walking herbivore from Eurasia, with the head of a horse. Its forelimbs were elongated and tipped with long claws. Its hind limbs were shorter, and it probably spend a long time sitting back on them. Despite this, Chalicotherium was a peaceful animal. It used its claws to pull branches down and munch on soft vegetation. It probably walked on its knuckles to avoid wearing the claws down. Juveniles had incisors and canine teeth at the front of their jaw, like we do, but as they matured, the teeth fell out and weren’t replaced, leaving only the molars. When they were younger and smaller, they probably only had access to the tougher plants close to the ground. But as they matured and could reach higher plants, they no longer needed teeth for cutting and stripping leaves. Adult Chalicotherium were probably picky eaters. And since they were the tallest animals in their ecosystems, they could afford to be. As far as we know, there weren’t any other animals gunning for that good, good vegetation up there. Or at least, not animals that could reach it.

Chalicotherium was an odd-toed ungulate, and its closest living cousins are tapirs, horses, and rhinos. The Chalicothere family was long-lived, first evolving from small woodland types in the Eocene. Their ancestors probably looked a lot like early horses, chubby little animals with short toes. As grasslands became increasingly prevalent in the Cenozoic, Chalicotheres diverged into two groups: One that stayed in the woodlands and took care of business as usual, and another group that took advantage of this strange new ecosystem and populated the grasslands. Chalicotherium belonged to the latter. The family survived until surprisingly recently, with the most recent member living until about 700,000 years ago.

Depending on who you ask, Chalicotherium might even still be hanging around (DISCLAIMER: Almost certainly not). A Kenyan cryptid called the Nandi Bear has been speculated by some to be a Chalicothere, given the description of an animal with a sloped back and sharp claws. Although, the Nandi Bear is supposed to be a carnivore, so that doesn’t really vibe with our friend the Chalicotherium. According to local tradition, the Nandi Bear eats only the brains of its victims, and that’s definitely not what this animal was about. Chalicotherium just wanted to wander around and eat leaves. It wasn’t a violent animal. So yeah, it’s not true, but it’s fun to talk about.

I’ve wanted to draw Chalicotherium for a while. It’s such a bizarre animal, and I love the detail with which we can analyze the mammals of the Cenozoic. I first heard about this family from Walking with Beasts. I’ve kind of inadvertently covered most of the animals from “Land of Giants”. The first mammal I talked about was the star of that episode, Paraceratherium, and the last Cenozoic animal I discussed was an Entelodont. Oh well. I just think they’re neat.

Post link