#post-colonial theory

Since finishing up my undergraduate studies in June, one of the major things I’ve been doing with my free time is playing Animal Crossing: New Horizons (please don’t @ me but I’ve already logged something like 400 hours). As much fun as the game is, one of the things that’s really stood out to me is how much AC:NH depends on and reifies colonial logics, and how important it is to unpack this in the context of the game’s popularity and the ongoing pandemic.

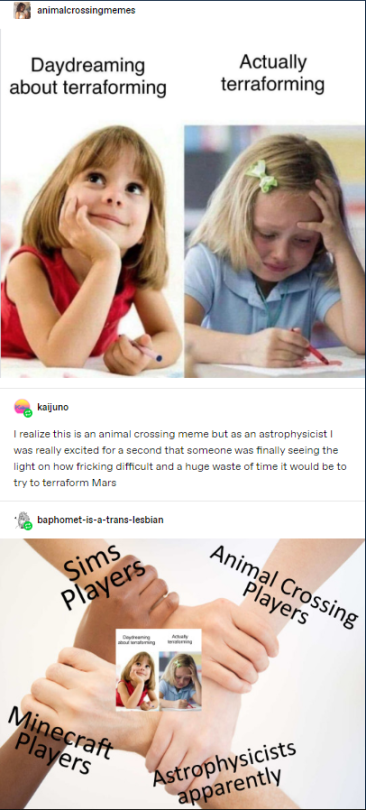

One of the first ways I want to address colonialism in AC:NH this is through the way I was first introduced to it, namely through its connection to my thesis and what I refer to as the “terraforming imaginary”. Before I started playing or had even decided to buy the game, I was working on my thesis “Constructing New Worlds: An Investigation of Climate Change and the Terraforming Imaginary” (which, shameless self plug but if you’re interested you can check out my 10 minute video presentation for symposium at Johns Hopkins University here). During this time I was talking about my thesis pretty non-stop with anyone who would listen and as a result probably about half of my friends independently sent me this meme

[ID: meme from @animalcrossingmemes which shows two children; the one on the left is smiling and looking off into the distance with the label “daydreaming about terraforming” while the child on the right looks stressed and upset with the label “actually terraforming”. Beneath this meme is text from @kaijuno which reads “I realize this is an animal crossing meme but as an astrophysicist I was really excited for a second that someone was finally seeing the light on how fricking difficult an a huge waste of time it would be to try to terraform Mars”. Beneath this text is another meme with four hands gripping each other’s wrists to make a circle. In the center is the initial animalcrossingmemes image and each arm is labeled, respectively, “Minecraft Players,” “Sims Players,” “Animal Crossing Players,” and “Astrophysicists apparently”]

Although my thesis addresses terraforming in the context of space exploration/colonization, AC:NH’s engagement with “terraforming” (alongside other aspects of colonial practices and desires) helps to expand on the stakes of this. The reason I put “terraforming” in scare-quotes is because…technically, there isn’t any terraforming in AC:NH, given that terraforming is “the operation consisting of rendering other stellar bodies—mainly planets and eventually asteroids—appropriate for human life” (Frédéric Neyrat, 46). While I’m all down for an interpretation of the Animal Crossing world as a non-Earth planet and the villagers as aliens, the island is already suitable for human life and the use of “terraforming” in the game is generally more readily identifiable as geoconstructivism: players redesign and restructure their islands, shaping waterways and topography to create idealistic spaces (as opposed to making the island literally livable). Either way, it speaks to the terraforming imaginary—the underlying set of logics and desires conducive to the imagining and desiring of “terraforming”, ie the logics and desires of colonization. Even though AC:NH’s terraforming isn’t technicallyterraforming, it is an embodiment of the terraforming imaginary, centering desires for the “civilizing”/“cultivating” of a space into an orderly, colonized ideal. On even a very surface level it is useful to think about this through the island rating system: islands are ranked out of five stars, with deductions made for things such as having “too many” weeds or not “cleaning up” by leaving items lying around rather than placed with intention.

Another, perhaps more obvious, way in which AC:NH embodies colonial logics is through the “Nook Miles Tickets”. Players trade in Nook Miles (an achievement based currency) for tickets which they can take to the airport and use to visit other, uninhabited islands which they can destroy to extract all of the resources slash-and-burn style. Players also have an increased likelihood of catching rare insects, fish, and sea animals to display to their own island museum or sell. As Wilbur, a dodo pilot, explains about this process: “we run the ‘finders keepers’ protocol here. Lumber, fruit, fish, whatever? Yours if you can carry it”, going on to emphasize the importance of not leaving anything behind as there will be no returning; they “burn the flight plans” after each flight.

Although the rampantly destructive extraction of resources is the most apparent embodiment of colonial logics, the centrality of the museum and the imperative to complete each wing by finding and identifying all of the bugs, fish/sea creatures, fossils, and artworks in the game is an equally significant connection to colonialism. Benedict Anderson argues in Imagined Communities that the museum, along with the census and the map, “shaped the way in which the colonial state imagined its dominion—the nature of the human beings it ruled, the geography of its domain, and the legitimacy of its ancestry” (164). The specifics Anderson goes into differ of course, because he’s talking about actual colonial states while AC:NH has the fluidity of embodying the underpinning desires which colonialism as process requires to function, but what holds true is that these specific forms of producing, organizing, and displaying knowledge which produced “a totalizing classificatory grid, which could be applied with endless flexibility…to be able to say of anything that it was this, not that; it belonged here, not there” (Anderson 184). Essentially, in AC:NH part of a player’s ownership of the island occurs through a player’s ability to classify and collect artefacts for the museum. Furthermore, this imperative to collect and preserve fossils, art work, bugs, fish, and sea creatures is part of the way the player’s island is positioned as a place of value.

The museum also implicitly functions to reify positions of authority, legitimizing a kind of monopoly of knowledge. In AC:NH, this primarily means the positions of the museum curator (Blathers) and, to a degree, Tom Nook (who selected and invited Blathers) are secured as the authorities on knowledge. When Tom Nook tells the player that the island(s) are deserted, we must take this as truth…yet fishing both on the player’s island and the Nook Miles islands can turn up trash items like old tires, tin cans, and boots. Colonial logics depend on a management of who counts as “people” and what counts as “inhabited” and the myth of empty lands; Tom Nook’s instance that these islands are all deserted is haunted by these lingering traces of some other inhabitation prior to the game’s start.

Okay, so you might be asking what does this all mean and why should we care? Let’s talk about both the game’s popularity and the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic which contextualized its release (and continues to shape daily life). Animal Crossing: New Horizons has not only received overwhelmingly positive critical reception, but is one of the best selling games both for the Switch console and the Animal Crossing series. According to freelance journalist Imad Khan’s New York Times article “Why Animal Crossing Is the Game for the Coronavirus Moment,” the game’s appeal centers in its function as an escape to an “island paradise where bags of money fall out of trees and a talking raccoon can approve you for a mortgage”. Khan quotes Dr. Ramzan (a professor of game narrative at Glasgow Caledonian University) who refers to it as “the universe you’ve always wanted, but can’t get.” Given the significantly decreased mobility and connection that has accompanied social distancing, as well as the increased stress and heightened inequality which have accompanied COVID-19, this probably isn’t particularly surprising. It makes sense that a cute, low-stress video game would be a valuable form of escapism.

Mobility is a particularly fraught discourse in this context: on the one hand, concerns surrounding containment/immobility are heightened in the context of neoliberalism and within colonial societies, which depend upon discourses of individualism and independence to demarcate the “freedom” which comes from capitalist economies. At the same time, the desire for things like connection/community, movement, and spatial autonomy/sovereignty are not inherently colonial, even as colonialist logics frequently position colonial/capitalist/neoliberal expansion as the solution. Animal Crossing is heavily situated within this entanglement, simultaneously offering a very real form of connection (and even protest) for many people while also implicitly speaking to latent beliefs that colonization is a legitimate form of mobility and escapism. To say that AC:NH is the universe we’ve always wanted but can’t get is to refuse to engage with the inherent contradictions of neoliberalism and reafirm the notion that colonial capitalist worlds are worth wanting; that the fantasy of individual wealth and success through destructive extraction and market freedom, when obtainable, is good.

None of this is to say that playing AC:NH is the same as colonization, because of course it isn’t. However, the colonial undertones of the game reflect the pervasiveness of colonial logics and desires in our daily lives, subsequently further normalizing them. Journalist Kazuma Hashimoto, for example, emphasizes the importance of contextualizing AC:NH’s colonial undertones within Japanese Colonialism in “Animal Crossing: New Horizons and Japanese Colonialism”. As Hashimoto argues, “I am only asking that people familiarize themselves with Japanese colonialism and why something as innocuous as discovering a deserted island can be read as colonialism — especially within the context of a Japanese game”.

Inattentiveness to the more subdued, invisibilized manifestations of violence facilitates their internalization and acceptance; educating ourselves and paying attention to and challenging places where we feel comfortable with these kinds of escapist fantasies is an important exercise in critical thinking which can help us to continue to refuse their real life manifestations.

I saw Dora and the Lost City of Gold (2019) at a local cheap theater with one of my friends last night and, to quote my friend, it was “wild”. Overall Dora is a fun movie that offers very important and positive Latine representation, and most of the minor things that bothered me (lack of narrative cohesion, the unrealistic absence of the sheeramount of paper involved in actualarchaeology) certainly wouldn’t bother the core demographic (children). However, Peter Debruge, writing for Variety, commented:

““Dora and the Lost City of Gold” goes out of its way to establish that the character isn’t a tomb raider or a treasure hunter, but rather an explorer, risking her life for the love of knowledge. That ranks her as perhaps the most “woke” big-screen adventurer since the invention of cinema, making Indy’s indignant “That belongs in a museum!” seem so 20th century by comparison” (“Film Review: ‘Dora and the Lost City of Gold’”).

This is where, I think, we get into some trouble. Spoilers below.

There are, on the surface, some obvious differences between a “treasure hunter” and an “explorer.” Treasure hunting is destructive and extractive, taking artifacts based on how high their potential resale value might be, with a complete disregard for the surrounding artifacts/environment, let alone the cultural meaning of the either artifact being extracted or the things being destroyed to retrieve it. An explorer, we are told, doesn’t take the gold.

“Exploration” and “explorer,” however, are highly loaded terms. Exploration is intrinsically linked to colonialism and imperialism, and explorers have historically been central to the production of knowledge and the generation of public and private interest which paved the way for colonization. They have also, historically, taken the gold. This is highly evident in the way that Cambridge Dictionary defines “explorer” as “a person who travels to places where no one has ever been to learn about them” because if explorers go where no one has ever been and explorers go to places where people of color have lived and are actively living, we now know who counts as a person and who doesn’t. To be fair, this specific phrasing is not a universal definition, but other definitions still contain the same problematics. Google Dictionary, for example, defines “explorer” as “a person who explores an unfamiliar area; an adventurer”. Here we can maybe concede that the “unfamiliar area” is unfamiliar to the person exploring it not an area that “no one” is familiar with, but again when we consider how the term is applied, explorers implies an emptiness to the region being explored: someone on vacation might “explore” the city of New York, but they wouldn’t be considered an explorer for doing so.

This leads us into the problematic of “jungle puzzles.” The phrase is first used in the movie by Randy, the cliche socially awkward nerd, after they have fallen into an aquifer. Dora and Randy both notice that the star map on the roof is wrong, prompting Randy to say it must be a jungle puzzle and pull a lever at random in order to correct the star alignment and reveal something hidden. Dora says there is no such thing as jungle puzzles, the room begins to fill with water, and they realize the star map was in fact accurate the whole time and they had just been looking at it wrong. This scene offers an excellent subversion of the “jungle puzzle” trope which is so often utilized in jungle-action/explorer flicks. In the images and rhetoric of colonialism, we frequently see the “challenge as invitation” theme appear, and often in ways which are very violently sexualized. This model is not only applied to colonial imaginings of colonized women/women of color, but to the feminized land itself, and it is very much as rape-y as this implies. The entire jungle puzzle trope is centered around the idea that ancient and/or indigenous peoples built their cities and their civilizations in order to serve as “escape the room” tests of courage, morality, and knowledge for outsiders, rather than for actual use by the inhabitants of those cities/members of those civilizations. It carries over the idea that the challenge of solving the puzzle invites in explorers/colonizers, and often it further imagines a universal morality and understanding of value which the explorer/colonizer can access and succeed at. Because of this, having a scene where explorers believe that an element of indigenous civilization was designed for outsiders to “solve” in order to be “rewarded” only to realize that they not only misunderstood the accuracy of an Incan star map, but that the entire structure was just a regular part of Incan life that had nothing to do with outsiders is an important intervention.

Unfortunately, upon arrival at the city of Parapata this initial intervention is lost, as the children quickly realize there are in fact “jungle puzzles” both to enter the city and to view the giant golden monkey statue. I do want to emphasize here that between Indiana JonesandDora and the Lost City of Gold, it is obviously important and even radical to see the rugged individual (cishet white man) model of Indiana Jones replaced by four kids–two of whom are Latinx and one of whom is played by an Australian Aboriginal woman–working together, and this shift is apparent in the way they characters interact with the city and its guardians. However, because it uses the same tropes it has many of the same issues. Again, it imagines that the city was built as a test, but the problematics of this representation are heightened by the arrival of los guardidos perdidos/the lost guardians and the old woman who initially tried to keep both the treasure hunters and the explorers away from Parapata but in the scene leading up to Dora solving the final puzzle, transforms into a beautiful young Incan princess and allows Dora to attempt the puzzle.

First, as a separate but connected issue, the figure of the Incan princess also plays into the idea of indigenous peoples as mystical/mysterious, ancient, and displaced from/frozen in time. First of all, I again want us to think about definition and application; according to Google Dictionary “ancient” means “belonging to the very distant past and no longer in existence.” The Incan Empire fell in the 1530s under Spanish conquest and the Incan people still exist today; when we look at Europe, Stonehenge is ancient; you don’t ever hear about the “ancient” art of Leonardo di Vinci, and he was dead and buried for more than a decade before the Incan Empire was destroyed. While we are not told where the guardians or the princess comes from, what we are implicitly told by an de-aging of the Incan princess is that they seem to be connected to the “ancient” empty city rather than contemporary Incan society, and subsequently that there are no modern Incan peoples, or that the modern Inca are irrelevant to this story. Against this lack of contemporary Incan indigeneity, Dora refers to the student body of a Los Angeles high school as its “indigenous population” several times throughout the film; it is imperative to consider how this undermines modern indigenious communities and their experiences.

Furthermore, the figure of the old-young princess fully leans into the sexually exploitative imagingings of colonized peoples/cities/lands as desiring of the entrance of outsiders; as an old woman, the princess’s role is to warn away, but as the young woman her role is to invite in the worthy, with the worthy being those who are able to solve the puzzle. Dora says she wants to learn, and the princess allows her to attempt the puzzle, but what exactly is Dora supposed to be learning (it seems the reward for the puzzle is the ability to view a giant gold statue of a monkey) and, more importantly, why is the entire city centered around this test?

Caitlin Wood’s 2014 edited volume Criptiques consists of 25 articles, essays, poems, songs, or stories, primarily in the first person, all of which are written from disabled people’s perspectives. Both the titles and the content are meant to be provocative and challenging to the reader, and especially if that reader is not, themselves, disabled. As editor Caitlin Wood puts it in the introduction, Criptiques is “a daring space,” designed to allow disabled people to create and inhabit their own feelings and expressions of their lived experiences. As such, there’s no single methodology or style, here, and many of the perspectives contrast or even conflict with each other in their intentions and recommendations.

The 1965 translation of Frantz Fanon’s A Dying Colonialism, on the other hand, is a single coherent text exploring the clinical psychological and sociological implications of the Algerian Revolution. Fanon uses soldiers’ first person accounts, as well as his own psychological and medical training, to explore the impact of the war and its tactics on the individual psychologies, the familial relationships, and the social dynamics of the Algerian people, arguing that the damage and horrors of war and colonialism have placed the Algerians and the French in a new relational mode.Read the rest of Criptiques and A Dying ColonialismatTechnoccult

In Ras Michael Brown’s African-Atlantic Cultures and the South Carolina Lowcountry Brown wants to talk about the history of the cultural and spiritual practices of African descendants in the American south. To do this, he traces discusses the transport of central, western, and west-central African captives to South Carolina in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries,finally, lightly touching on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Brown explores how these African peoples brought, maintained, and transmitted their understandings of spiritual relationships between the physical land of the living and the spiritual land of the dead, and from there how the notions of the African simbi spirits translated through a particular region of South Carolina.

In Kelly Oliver’s The Colonization of Psychic Space, she constructs and argues for a new theory of subjectivity and individuation—one predicated on a radical forgiveness born of interrelationality and reconciliation between self and culture. Oliver argues that we have neglected to fully explore exactly how sublimation functions in the creation of the self,saying that oppression leads to a unique form of alienation which never fully allows the oppressed to learn to sublimate—to translate their bodily impulses into articulated modes of communication—and so they cannot become a full individual, only ever struggling against their place in society, never fully reconciling with it.

These works are very different, so obviously, to achieve their goals, Brown and Oliver lean on distinct tools,methodologies, and sources. Brown focuses on the techniques of religious studies as he examines a religious history: historiography, anthropology, sociology, and linguistic and narrative analysis. He explores the written records and first person accounts of enslaved peoples and their captors, as well as the contextualizing historical documents of Black liberation theorists who were contemporary to the time frame he discusses. Oliver’s project is one of social psychology, and she explores it through the lenses of Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalysis,social construction theory, Hegelian dialectic, and the works of Franz Fanon. She is looking to build psycho-social analysis that takes both the social and the individual into account, fundamentally asking the question “How do we belong to the social as singular?”Read the rest of Selfhood, Coloniality, African-Atlantic Religion, and Interrelational CutlureatTechnoccult

Elizabeth A Wilson’s Affect and Artificial Intelligence traces the history and development of the field of artificial intelligence (AI) in the West, from the 1950’s to the 1990’s and early 2000’s to argue that the key thing missing from all attempts to develop machine minds is a recognition of the role that affect plays in social and individual development. She directly engages many of the creators of the field of AI within their own lived historical context and uses Bruno Latour, Freudian Psychoanalysis, Alan Turning’s AI and computational theory, gender studies,cybernetics, Silvan Tomkins’ affect theory, and tools from STS to make her point. Using historical examples of embodied robots and programs, as well as some key instances in which social interactions caused rifts in the field,Wilson argues that crucial among all missing affects is shame, which functions from the social to the individual, and vice versa.

J.Lorand Matory’s The Fetish Revisited looks at a particular section of the history of European-Atlantic and Afro-Atlantic conceptual engagement, namely the place where Afro-Atlantic religious and spiritual practices were taken up and repackaged by white German men. Matory demonstrates that Marx and Freud took the notion of the Fetish and repurposed its meaning and intent, further arguing that this is a product of the both of the positionality of both of these men in their historical and social contexts. Both Marx and Freud, Matory says, Jewish men of potentially-indeterminate ethnicity who could have been read as “mulatto,” and whose work was designed to place them in the good graces of the white supremacist, or at least dominantly hierarchical power structure in which they lived.

Matory combines historiography,anthropology, ethnography, oral history, critical engagement Marxist and Freudian theory and, religious studies, and personal memoir to show that the Fetish is mutually a constituting category, one rendered out of the intersection of individuals, groups, places, needs, and objects. Further, he argues, by trying to use the fetish to mark out a category of “primitive savagery,” both Freud and Marx actually succeeded in making fetishes of their own theoretical frameworks, both in the original sense, and their own pejorative senses.

Read the rest of Affect and Artificial Intelligence and The Fetish RevisitedatTechnoccult

Caitlin Wood’s 2014 edited volume Criptiques consists of 25 articles, essays, poems, songs, or stories, primarily in the first person, all of which are written from disabled people’s perspectives. Both the titles and the content are meant to be provocative and challenging to the reader, and especially if that reader is not, themselves, disabled. As editor Caitlin Wood puts it in the introduction, Criptiques is “a daring space,” designed to allow disabled people to create and inhabit their own feelings and expressions of their lived experiences. As such, there’s no single methodology or style, here, and many of the perspectives contrast or even conflict with each other in their intentions and recommendations.

The 1965 translation of Frantz Fanon’s A Dying Colonialism, on the other hand, is a single coherent text exploring the clinical psychological and sociological implications of the Algerian Revolution. Fanon uses soldiers’ first person accounts, as well as his own psychological and medical training, to explore the impact of the war and its tactics on the individual psychologies, the familial relationships, and the social dynamics of the Algerian people, arguing that the damage and horrors of war and colonialism have placed the Algerians and the French in a new relational mode.

Read the rest of Criptiques and A Dying ColonialismatTechnoccult

In Ras Michael Brown’s African-Atlantic Cultures and the South Carolina Lowcountry Brown wants to talk about the history of the cultural and spiritual practices of African descendants in the American south. To do this, he traces discusses the transport of central, western, and west-central African captives to South Carolina in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries,finally, lightly touching on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Brown explores how these African peoples brought, maintained, and transmitted their understandings of spiritual relationships between the physical land of the living and the spiritual land of the dead, and from there how the notions of the African simbi spirits translated through a particular region of South Carolina.

In Kelly Oliver’s The Colonization of Psychic Space, she constructs and argues for a new theory of subjectivity and individuation—one predicated on a radical forgiveness born of interrelationality and reconciliation between self and culture. Oliver argues that we have neglected to fully explore exactly how sublimation functions in the creation of the self,saying that oppression leads to a unique form of alienation which never fully allows the oppressed to learn to sublimate—to translate their bodily impulses into articulated modes of communication—and so they cannot become a full individual, only ever struggling against their place in society, never fully reconciling with it.

These works are very different, so obviously, to achieve their goals, Brown and Oliver lean on distinct tools,methodologies, and sources. Brown focuses on the techniques of religious studies as he examines a religious history: historiography, anthropology, sociology, and linguistic and narrative analysis. He explores the written records and first person accounts of enslaved peoples and their captors, as well as the contextualizing historical documents of Black liberation theorists who were contemporary to the time frame he discusses. Oliver’s project is one of social psychology, and she explores it through the lenses of Freudian and Lacanian psychoanalysis,social construction theory, Hegelian dialectic, and the works of Franz Fanon. She is looking to build psycho-social analysis that takes both the social and the individual into account, fundamentally asking the question “How do we belong to the social as singular?”

Read the rest of Selfhood, Coloniality, African-Atlantic Religion, and Interrelational CutlureatTechnoccult

One of the things I’m did this past spring was an independent study—a vehicle by which to move through my dissertation’s tentative bibliography, at a pace of around two books at time, every two weeks, and to write short comparative analyses of the texts. These books covered intersections of philosophy, psychology, theology, machine consciousness, and Afro-Atlantic magico-religious traditions, I thought my reviews might be of interest, here.

My first two books in this process were Frantz Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks and David J. Gunkel’s The Machine Question, and while I didn’t initially have plans for the texts to thematically link, the first foray made it pretty clear that patterns would emerge whether I consciously intended or not.

[Image of a careworn copy of Frantz Fanon’s BLACK SKIN, WHITE MASKS, showing a full-on image of a Black man’s face wearing a white anonymizing eye-mask.]

In choosing both Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks and Gunkel’s The Machine Question, I was initially worried that they would have very little to say to each other; however, on reading the texts, I instead found myself struck by how firmly the notions of otherness and alterity were entrenched throughout both. Each author, for very different reasons and from within very different contexts, explores the preconditions, the ethical implications, and a course of necessary actions to rectify the coming to be of otherness…

Read the rest of Colonialism and the Technologized Otherat Technoccult.net