#ptolemy

I go insane thinking about Bartimaeus and Ptolemy sometimes.

It’s been over two thousand years, and I cannot even hope to conceive how long that is, but Bartimaeus still carries Ptolemy with him at all times. His default shape is that of Ptolemy to the point where people like Kitty and Nathaniel automatically associate it with Bartimaeus. He constantly thinks about Ptolemy, referencing him whenever human/spirit bonds are mentioned, comparing Kitty and Nathaniel to him, etc. He is never not thinking about Ptolemy. There are people I see every day that I think about less than Bartimaeus thinks about Ptolemy. Every interaction with humans and every moment on earth is colored by his time with Ptolemy, and Bartimaeus is so aware of that

Like despite only showing up on screen for like 5 or so short chapters, Ptolemy is such a big presence that he feels like the fourth major character after the main pov three because that’s how important he was to Bartimaeus, that’s how much Bartimaeus loves him

Ptolemy has been dead for almost half of Bartimaeus’s life, but his ghost pervades the entire series because Bartimaeus is holding on to his memory too tightly to let it fade away

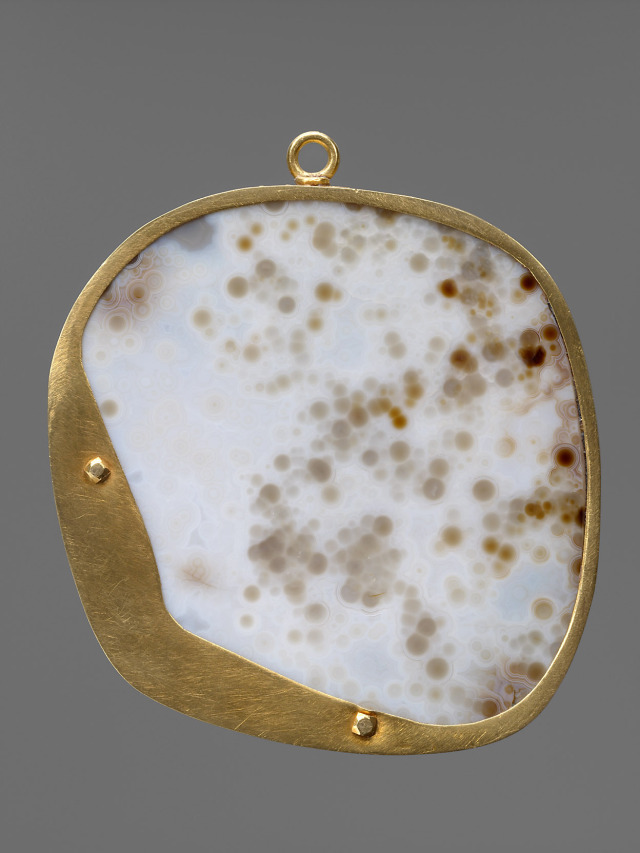

~ Ptolemaic Cameo.

Culture: Greek

Period: Hellenistic

Date: 278-269 B.C.

Medium: Ten-layered Arabic Onyx, dark brown and bluish white. Setting: gold ring, enamel, 4th quarter of the 16th century.

~ Votive relief fragment depicting the cobra-goddess Wadjet, the creator god Khnum in the form of a ram, and the goddess of truth, Ma‘at.

Place of origin: Egypt

Period/Culture: Ptolemaic Period

Medium: Limestone

Detail of a miniature of the dragon constellation (‘Draco’), in tables from Ptolemy’s Almagest.

From “Amalgest (extract), Liber Astronomiae, Liber Arenalis, astronomical and geomantic tables, political prophecies” by John Killingworth, Ptolemy, Guido Bonatti & Plato of Tivoli, 1490.

•

Follow for more: Instagram|Pinterest

Post link

The BP exhibition Sunken cities: Egypt’s lost worldsfeatures incredible sculptures excavated from beneath the waves. Here, Exhibition Curator Aurélia Masson-Berghoff tells us about one of these magnificent works – her favourite object in the show:

‘This statue is a personal favourite, not only for the utmost quality of the carving of this very hard Egyptian stone, but also because of who it is and what it stands for. This is Arsinoe II, a deified queen who bridged Egyptian and Greek religious traditions. Like the famous Cleopatra VII, Arsinoe was a powerful royal woman of the Ptolemaic dynasty, the Greco-Macedonian dynasty that ruled over Egypt for almost 300 years (305–30 BC).

‘Arsinoe was the eldest daughter of Ptolemy I, the founder of the Ptolemaic dynasty. In a third wedding, she married her brother Ptolemy II, who promoted the worship of his sister-wife after her death. She was sometimes recognised by Egyptians as Isis, mother goddess and patron of magic, and was worshipped extensively by Egyptians and Greeks alike. A royal decree proclaimed that a statue of the queen had to be placed in every temple in Egypt. There are many representations of Arsinoe II, most of them made after her death, with examples in pharaonic, Greek and Greco-Egyptian styles.

‘This supreme example discovered at Canopus is a perfect combination of Egyptian and Greek styles. While the choice of a local dark stone and the queen’s striding posture are typically Egyptian, the sensual rendering of her flesh, revealed through the play of the transparent garment, is reminiscent of Greek masterpieces. The slightly over-lifesize sculpture echoes the work of the Athenian sculptor Kallimachos (second half of the 5th century BC), such as his Venus Genetrix which shows a similar treatment of the fine, clinging drapery. The Ptolemaic queen here embodies Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of beauty, who was believed to bestow good fortune on sailors.

‘What I find truly remarkable with this statue is Arsinoe’s attitude. She has this modern flare about her. She exudes confidence. Her posture is poised, almost athletic, far from the more charming indolence usually displayed in marbles representing Aphrodite.’

Granodiorite statue of Arsinoe II. Canopus, 3rd century BC. Bibliotheca Alexandrina Antiquities Museum. Photo: Christoph Gerigk. © Franck Goddio/Hilti Foundation.

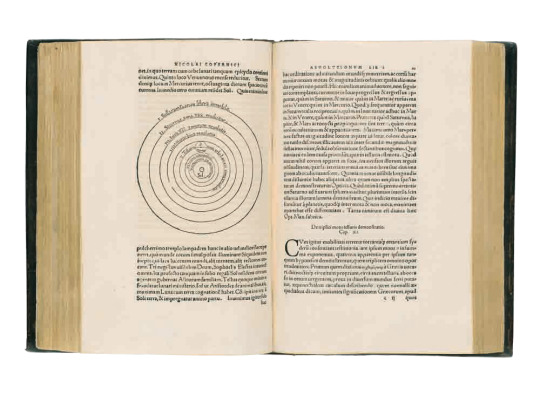

Nicolaus Copernicus was born on 19 February 1473. It was his work that popularised the heliocentric astronomical model - the understanding that the Earth revolves around the Sun and not vice versa.

The Bodleian Libraries hold several copies of Copernicus’ De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres),one of which was displayed in our Marks of Genius exhibition (you can see two pages at the head of this post).

Our most notable copy, perhaps, is the one to bear the shelfmark Savile N 12 (3). It comes from the library of Henry Savile, Warden of Merton College, friend of Thomas Bodley, and in 1619, the founder of the two University of Oxford scholarships that still bear his name. His collection of scientific books was transferred to the Bodleian in 1884.

It is understood that Savile deeply respected Copernicus’s achievements as an astronomer but did not necessarily agree with his conclusions. Therefore, he taught his students in the 16th century University of Oxford the Copernican and Earth-centred Ptolemaic systems side by side (both of which still proposed that the stars and planets were fixed in a series of celestial spheres), and would not have been troubled by expressing these contradictory models side by side.

We can only imagine how much dispute there might have been amongst his students…

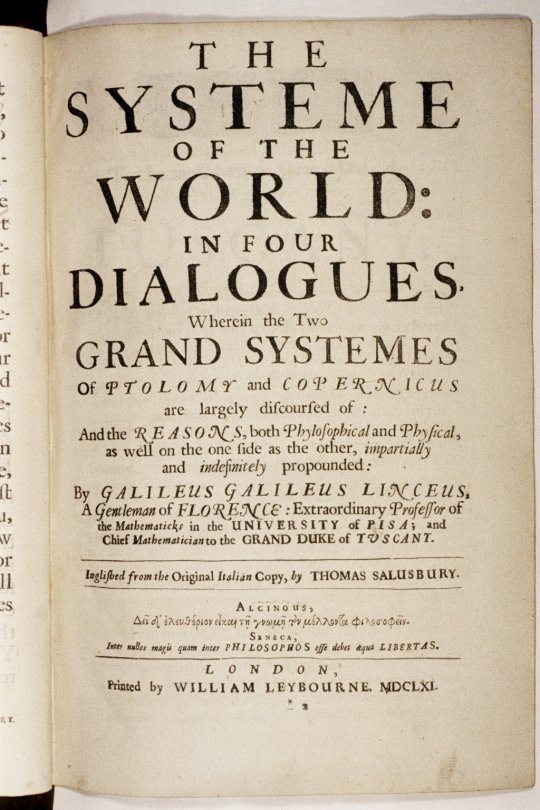

…which brings us to the works of Galileo Galilei. In 1632, Galileo published Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems(Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo), later translated by Thomas Salisbury as The Systeme of the World: in Four Dialogues.

This book dramatised a series of disputes over Copernican and Ptolemaic views of astronomy. If you’d like to take a look at a Bodleian Libraries copy right now, several pages have been digitised and made available online, a couple of which appear below.

#بلادي_الجميلة ❤ #مصر ❤

The Death of Cleopatra artist: John Collier, 1890.

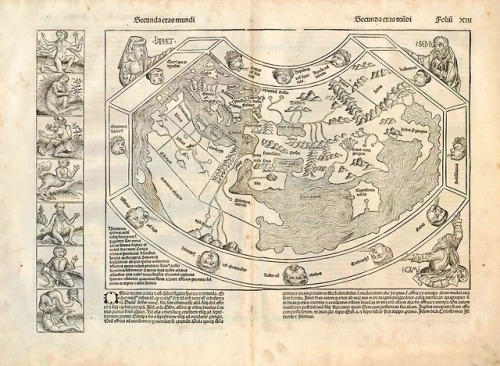

Our current exhibitionin the special collections–our two copies of the Liber Cronicarum (aka, the Nuremberg Chronicle) of 1493–is presently showing the oldest map in the collection: this view of world. While it’s printed in 1493, it’s based on a much older map by Ptolemy, and it shows Noah’s three sons (Japeth, Shem, and Ham) holding up the world while the classical twelve-winds blow around it all. We’re turning pages in both volumes, so come visit this week to see this glorious woodcut map…

Post link