#rule of law

[Image ID: a tweet thread by Nazir Afzal, @nazirafzal. The first tweet reads:

“Boris Johnson is the first sitting prime minster to be judged guilty of a crime

Sunak the first Chancellor to be fined

Carrie the first PM’s wife to be fined

Downing Street is a crime scene”

It is tagged #Partygate.

The second reads:

“Let’s be clear this is the most atrocious leadership during the worst public crisis since WW2

He made the law

We complied with the law at great personal cost - all of us

He & his Govt broke the law

Without the rule of law, there is no democracy”

The third reads:

“To those saying ‘now is not the time’ for Johnson to resign

Those of us who lost loved ones to covid & couldn’t attend funerals also believed that 'now was not the time’

But we responded to the greater good, we decided to comply with the law & we made sacrifices while he didn’t”

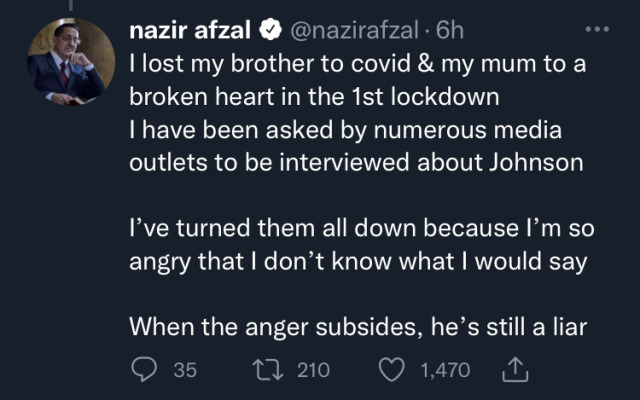

The third reads:

“LAW BREAKERS CANNOT BE LAW MAKERS”

It is tagged #BorisJohnson, #RishiSunak, #TheRestOfThem, and #Partygate.

The last reads:

“I lost my brother to covid & my mum to a broken heart in the 1st lockdown

I have been asked by numerous media outlets to be interviewed about Johnson

I’ve turned them all down because I’m so angry that I don’t know what I would say

When the anger subsides, he’s still a liar”

End ID]

In the history of jurisprudence generally, and in German law in particular, the royal intervention in the Millers Arnold case is infamous for being a violation of judicial independence and thus an act of executive overreach that threatens the foundation of rule of law; that it corrected a manifest injustice is not seen as bearing significantly on the problems of the case, and you may draw what parallels you like with yesterday’s exploration of suo motu actions by courts in South Asia, especially as they converge with public interest litigation in India.

Rule of law is a crucial element of not only a just society in general, but the Great Compromise of liberalism in particular. It’s important to the former, because it’s a component of a predictable rules-based system that ensures equal protection under and equality before the law, and to the latter because a predictable and institutions-based system where avenues of reform are known and consensus-building methods available allows for social systems where people don’t have to worry that, unless they seize power through violence and maintain it by repression, they might suffer intolerably or actually be killed. This is a massively important component of why we don’t, for instance, have to have a succession war every time the executive changes, and in just about every case of violent upheaval in previously peaceful societies I would argue that you can show that either the Great Compromise failed or was never operative.

But rule of law on its own is not justice. This is something that in modern times German jurists have had to struggle with quite notably, because authoritarian systems of government in the 20th and 21st have often been very particular about preserving the forms of rule of law, while getting the outcomes they wanted. This is true of all manner of personalist and populist regimes, and can be seen in Hungary, Poland, and Russia today, but it’s also true of ideological regimes who, even if they may contest specific principles that are seen as integral to rule of law in other countries, like free speech, an independent judiciary or free elections, are still at pains to frame their overall institutions as legitimate, democratic, and principled.

In the postwar era, this principle had to be grappled with in Germany as pro-democracy politicians and jurists had to struggle to articulate what exactly had failed in 1933, how the German state afterward could be treated as illegitimate, even though the formal institutions of the Weimar constitution had remained intact, and how they could build a just and democratic system going forward, which necessarily required repudiating a period of bloody lawlessness, no matter how much it had tried to cloak itself in the law. This is especially important for academic jurisprudence, which as I understand is more important in a civil law system, because legal principles are less often derived directly from judicial decisions (which are far weaker in their precedent-setting capacity) and more often derived from academic writing about the law (which influences and is influenced by the actions of the judiciary and the legislature).

Thus, modern German jurisprudence distinguishes rule of law from rule bylaw. Rule by law may conform to the appearance of rule of law, but it does not owe allegiance to more fundamental principles of justice: the law is an expedient to get the outcome you want, and not reflective of a set of deeper principles you’re trying to uphold through the rules and institutions you put in place. Rule oflaw requires that allegiance, and real rule of law might require opposing institutions or rules–even when procedurally correct–if they violate fundamental principles of justice. You might pass a law somewhere tomorrow, through all the correct methods of constitutional amendment and parliamentary procedure, declaring all left-handed people must pay the government $500 as a one-time tax on their stubborn and immoral behavior of writing with the wrong hand. Under real rule of law, such a law is invalid no matter how popular, how procedurally correct, or how evenly it is implemented, because it’s an inherently unjust act of oppression. No amount of legalistic procedure can rescue it, because it adheres to no principle other than “fuck left-handed people.”

This distinction is really important, because it goes to something about courts that the reams of commentary on Millers Arnold missed, which is that no court can be legitimate unless it actually renders good decisions. Yes, by ordering his courts to rule differently, Frederick II undermined the independence of the Prussian judiciary, and this may have weakened confidence in Prussian courts in the aftermath. It’s hard to have a rules-based system of government if the king often arbitrarily reverses decisions of his courts. But the real problem is deeper: it was a bad decision. If courts cannot be expected to render good decisions, a crisis of legitimacy will follow, because manifestly unjust courts are an equal or bigger problem for rule of law than judicial independence. In the modern world, where we rely on things like the Great Compromise to prevent violent revolution (Prussia did not have that; there’s a reason the Prussian monarchy no longer exists), courts that make bad decisions violate a fundamental tenet of the Compromise.

An intervention like Frederick’s, or like the suo motu actions of Indian courts, doesn’t really protect rule of law at the expense of rule by law; the best it can do is correct a unique injustice in a non-systematic way, and in that case it might be an individually positive outcome, albeit one that comes at a notable institutional cost. Ideally, it could help improve faith in systems of justice (or in the Compromise itself), while reform is pursued through other avenues, to prevent long-term harm and to reduce the need for such interventions in the first place. In practice it doesn’t seem to do that, unfortunately, meaning the downside is even greater, though correcting the individual injustice is still very good. If you do not have the opportunity for these one-off interventions by a higher authority to correct injustices, you improve the resilience of your institutions, which is usually a good thing. But you also lose an important valve for letting off pressure if those institutions are dysfunctional.

With the preliminaries out of the way, let’s talk about the US Supreme Court.

The US Supreme Court is going to overturn Roe v Wade, a decision which even many supporters of the political outcome think is decided on shaky theoretical grounds. Because of the way law is created and interpreted in common law systems, the theoretical grounds of a decision like Roe are more important than they would be in a civil law system, though my understanding is that the picture is more complicated than just a decision creating law: in principle two different decisions might reach the same conclusion based on different rationales, and it would be up to future judges in future cases to negotiate exactly which rationale they should use when interpreting the law going forward. Overturning a decision outright is rare, especially when you have the option of saying “okay, Case A rendered the right decision for the wrong reasons; in this case, we’re going to alter the reasoning a little bit to make interpretation of the law more consistent going forward.”

Maintaining Roe in some form is supported by an absolutely silly proportion of the US population, AFAICT; something like 65%, in an era when 65% of Americans can’t agree that the sky is in fact blue. Support for specific restrictions on abortion is much more varied, because this is a subject that politically the country is fairly ambivalent on, but the Supreme Court has many tools in its toolkit besides “let one court case from 1973 stand or fall on its own,” and outright reversal of that decision is likely to be broadly seen as a bad move. This, on its own, is not necessarily a problem: courts often have the job of making merely unpopular decisions in the name of justice. That doesn’t mean they’re failing to abide by higher principles. Sometimes–as in Loving v Virginia–it just means popular opinion is unprincipled.

I’m not actually concerned with Roe directly here, but I do think that Roe bears on the idea of a crisis of legitimacy in the Supreme Court, which the Court is rightly worried about. Unfortunately, the Court does not understand what the source of this crisis is: it is the fact that the Court has become concerned almost solely with rule by law, rather than rule of law. Much more indicative of this trend than Roe is Shinn v Ramirez, in which the court ruled that a mere probability of innocence isn’t enough to void a conviction, even in a capital case; more fundamental procedural violations must have occurred to prevent the penalty from being carried out (in this case, execution).

This is a huge problem. Isolated from external concerns–that is to say, in an abstract and theoretical void, which is where SCOTUS seems to dwell–procedure is indeed of great importance. Procedure is a component of an equal application of the law, a way to instrumentalize more fundamental principles in a way transparent to those who are subject to a court’s authority. But those fundamental principles still matter; indeed, they matter more than procedure, because rule of law is not the same as rule by law.

The fundamental principle at stake in a criminal trial is the guilt of the accused. If procedure cannot accommodate overturning a verdict which is incompatible with this principle, the procedure is unsalvagable. It is a violation of the very purpose of law; we may as well revert to mob violence, which at least doesn’t require paying bailiffs or maintaining expensive neoclassical buildings on valuable downtown real estate. If the Supreme Court cannot see the underlying principle beyond the screen of procedure, then the Supreme Court is setting its own legitimacy on fire. Overturning Roe is relevant here only insofar as it’s a manifestation of a broader trend of the Supreme Court setting its own legitimacy on fire, then complaining about the smell of smoke.

Moreover, this is not a new phenomenon. Shinn v Ramirez is part of a long line of tough-on-crime court decisions and legislative acts (especially in capital cases) that sacrifice fundamental principles in favor of smoothing procedure for state actors; on the basis of “reforming the death penalty” the right to habeas corpus was severely curtailed in 1996, with the fundamental principle of protecting the rights of the accused being sacrificed to the much more contingent procedural question of how easy it should be for the state to kill someone. Note also the raft of cases as the drugs commonly used in executions have become less available in the US; SCOTUS has repeatedly opted to weaken principles against cruel and unusual punishment rather simply require the state not to torture prisoners to death or not kill them if it can’t do it in a way compatible with the constitution, which is a startling reversal of principle is supposed to govern the law. Most peoples’ moral intuition, I suspect, is that while the law may permit the state to do a thing, if it cannot do the thing in a just manner, it should not do it; SCOTUS seems to think, however, that if the law permits the state to do a thing, then by definition it is possible to do in a just manner, regardless of the facts on the ground.

It is increasingly difficult to escape the conclusion that, especially as it pertains to criminal law and the death penalty in the US, the single most significant opponent to the rule of law is the Supreme Court. An institution as defensive and insular as the Supreme Court will not reform itself, nor do I expect external pressure to cause it to reform. If the rule of law is to be maintained in the United States–if the fundamental principles on which the law is built and which it is necessary to preserve to prevent that rule from being replaced by empty ritual that can reach arbitrary conclusions–then the Supreme Court must be destroyed. I do not believe it can be reformed. I do not believe any of its current justices are redeemable, since they are the product of a selection process which has consistently produced lawless outcomes. It must be replaced by an institution which hears cases more consistently, and therefore which has many more justices; this would also prevent the highly variable outcomes that result from selection effects and reduce the political fracas around individual appointments. Its members, and all federal judges, should be nominated through non-political means. And if nominees for the federal judiciary cannot agree that, as a matter of first principle, the state should not execute those who are actually innocent of the crime they are accused of, and should strive to its utmost ability to avoid that outcome, they should be entirely disqualified.

I needed context for this. This seemed reasonable, though clearly biased in the same direction of op

The Supreme Court just condemned a man to die despite strong evidence he’s innocent

https://www.vox.com/platform/amp/2022/5/23/23138100/supreme-court-barry-jones-shinn-ramirez

Note that this case exists in parallel to another trend, that of bad “forensic evidence” (essentially nonsense made up by self-styled experts without scientific support) used to effect dubious criminal prosecutions. One example is Cameron Todd Willingham, who was executed for murder based on false evidence. There has been increasing reporting in recent years of the unreliability of basically everything except DNA and fingerprinting, but this is the general prosecutorial environment that cases like this have arisen out of. Cf. also the You’re Wrong About episode on shaken baby syndrome, and for an older example, the one on the Satanic Panic.

IMO the willingness to allow a death penalty to be upheld despite major problems with the case is, like an enthusiasm by courts for bad evidence as long as it supports the prosecution’s theories, part of a general trend toward undermining foundational elements of criminal justice in favor of procedural facilitation of prosecution, as part of the reactionary “tough on crime” discourse that started in the 80s and 90s. The Supreme Court alone is not responsible for this trend, but the Supreme Court has most certainly facilitated it and offered legal theories to support it, including some spectacularly bad rulings around capital punishment specifically.

(That on top of this members of the court have the audacity to want to be treated as austere intellectuals operating in the rarefied realm of legal theory while they are personally responsible for the execution of innocents is incrediblygalling to me. The place to do theoretical work unconnected to actual instances of human suffering is academia, not actual courts, and clearly you don’t take the responsibility of your job seriously if you don’t appreciate the effect it has on the material conditions of the hundreds of millions of people in the country whose legal system you sit at the top of.)

Isn’t it interesting that Rowling chooses to let Harry, her star protagonist, commit two out of the three Unforgivable Curses during the course of the story, while still a teenager, and face no punishment?

Wasn’t one of the huge red flags about Voldemort that he tortured others with no remorse, just to satisfy his own curiosity or emotional desires?

Harry Potter, our hero, clearly has a whole lesson about Crucio, Imperio and Avada Kedavra in Goblet of Fire, in which he learns, aged 14, that each curse carries a life sentence. In the same class, he witnesses the cruel impact of each curse used on an animal.

Nonetheless, the very next year is the first time Harry tries to cast Crucio, the torture curse, on another human. At the age of 15.

We know from the great detail that the lesson goes into that the sole purpose of Crucio is to cause pain. Harry does not use Crucio to try and obtain information. He uses it to hurt a woman who he dislikes (albeit for valid reasons).

The very next year, Harry again uses Crucio against an adult he dislikes, deliberately in order to inflict pain. Yes, it’s during combat. But he is knowingly breaking the law of his land. Is he banking on his celebrity status to be above the law?

Finally, in his seventh year, Harry uses Crucio against an adult for the third time. This time, he hurts the adult so much that they become unconscious from the pain. Amycus Carrow had insulted a woman Harry liked in front of him.

In case anyone has forgotten, immediately after finishing school, Harry Potter takes a career in law enforcement. There’s no suggestion he faces any punishment whatsoever for what are essentially war crimes. Is this what JK Rowling intended?

I wonder what Neville thinks about his friend’s actions, given his personal history with Crucio? Isn’t a central theme of Harry Potter “do the ends justify the means?” What does the rule of law mean if members of law enforcement are given carte blanche to commit war crimes with no punishment?

Doesn’t that retroactively excuse Dolores Umbridge’s actions when she herself, representing the law, attempts to bait Harry into committing a crime and threatens him with torture?

Shall we even get into the issues of Hermione committing kidnap and blackmail, Ron stealing, the Weasley twins underage gambling? Maybe Harry Potter isn’t the Good series it makes itself out to be when such morally grey characters are the central protagonists and the legal system rewards them.

Hail Superwholock!

Though the shows are ending, the fandoms will stay strong!

Right now, there are legal challenges to the government’s Rwanda policy sitting in court. The first plane takes off tomorrow.

These deportations could later be ruled illegal, but by then it will be too late.

Don’t get me wrong, the organisations working hard to mount legal challenges etc are doing a good thing and deserve support.

But ultimately, the legal system is slow and protects the powerful, not the weak.

Sending vulnerable people seeking asylum to a country thousands of miles away, which they have no ties with, and which the UK has granted people asylum from very recently- that’s tantamount to murder.

If we wait for the legal system to work, people’s lives will be ruined, people may die.

Rule of law exists to protect the weak from the powerful, saying that those that govern must follow their own laws. It doesn’t exist to protect the government from the people.