#workforce

[For more analysis and commentary, please join me at robertreich.substack.com]

The General Strike of 2021

On Tuesday, the Labor Department reported that some 4.3 million people had quit their jobs in August. That comes to about 2.9 percent of the workforce – up from the previous record set in April, of about 4 million people quitting.

All told, about 4 million American workers have been leaving their jobs every month since last spring.

Add this to last Friday’s jobs report showing the number of job openings at a record high. The share of people working or actively looking for work (the labor force participation rate) has dropped to 61.6 percent. Participation for people in their prime working years, defined as 25 to 54 years old, is also down. Over the past year, job openings have increased 62 percent.

What’s happening? You might say American workers have declared a national general strike until they get better pay and improved working conditions.

No one calls it a general strike. But in its own disorganized way it’s related to the organized strikes breaking out across the land – Hollywood TV and film crews, John Deere workers, Alabama coal miners, Nabisco workers, Kellogg workers, nurses in California, healthcare workers in Buffalo.

Disorganized or organized, American workers now have bargaining leverage to do better.

After a year and a half of the pandemic, consumers have pent-up demand for all sorts of goods and services. But employers are finding it hard to fill positions.

This general strike has nothing to do with the Republican bogeyman of extra unemployment benefits supposedly discouraging people from working. Reminder: The extra benefits ran out on Labor Day.

Renewed fears of the Delta variant of COVID may play some role. But it can’t be the major factor. With most adults now vaccinated, rates of hospitalizations and deaths are way down.

Childcare is a problem for many workers, to be sure. But lack of affordable childcare has been a problem for decades. It can’t be the reason for the general strike.

I believe that the reluctance of workers to return to or remain in their old jobs is mostly because they’re fed up. Some have retired early. Others have found ways to make ends meet other than remain in jobs they abhor. Many just don’t want to return to backbreaking or boring low-wage shit jobs.

The media and most economists measure the economy’s success by the number of jobs it creates, while ignoring the *quality* of those jobs. That’s a huge oversight.

Years ago, when I was Secretary of Labor, I kept meeting working people all over the country who had full-time work but complained that their jobs paid too little and had few benefits, or were unsafe, or required lengthy or unpredictable hours. Many said their employers treated them badly, harassed them, and did not respect them.

Since then, these complaints have only grown louder, according to polls. For many, the pandemic was the last straw. Workers are burned out, fed up, fried. In the wake of so much hardship, illness and death during the past year, they’re not going to take it anymore.

To lure workers back, employers are raising wages and offering other inducements. Average earnings rose 19 cents an hour in September and are up more than $1 an hour – or 4.6 percent – over the last year.

Clearly, that’s not enough.

Corporate America wants to frame this as a “labor shortage.” Wrong. What’s really going on is more accurately described as a living-wage shortage, a hazard pay shortage, a childcare shortage, a paid sick leave shortage, and a health care shortage.Unless *these* shortages are rectified, many Americans won’t return to work anytime soon. I say it’s about time.

Post link

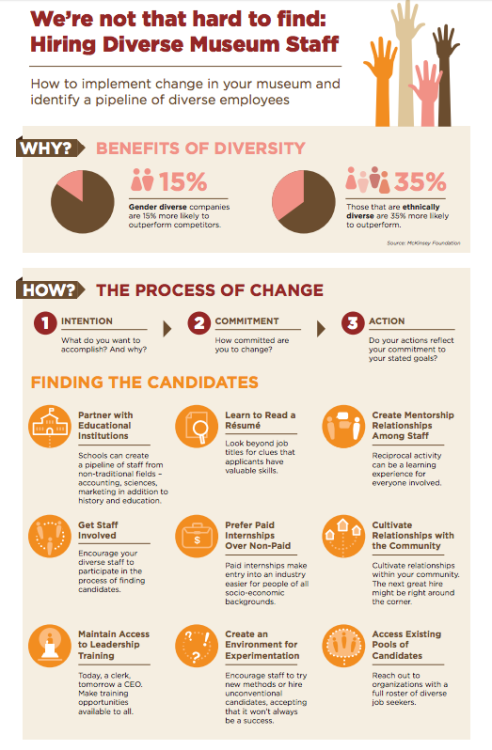

We’re Not That Hard to Find: Hiring Diverse Museum Staff

An infographic based on the guidelines by Joy Bailey-Bryant from the Jan/Feb edition of the AAM’s Museum about ways that museums can change their hiring and employment practices to encourage a more diverse and representative workforce.

Rather than just repeating the data we already know about the worrying lack of diversity in many areas of museum education and employment, this attempts to unpick some of the causes, offering concrete advice about engaged museum might enact change and help recruit a more diverse workforce. The reasons for a lack of diversity in the museum field are manifold, but this addresses some of the mechanisms that are in place that can tackled, such as unpaid internships, proper career support and management of existing staff, where positions are advertised, and looking more deeply at applicants to see identify skill sets that aren’t necessarily formal qualifications.

As classically interdisciplinary places of learning, museums can only thrive when their perspectives are as diverse as the audiences and communities that they serve. If museums seek to be representative, then their staffing and institutions need to be as well. We know that speaking for marginalised voices and groups is inadequate, here’s how to do something about it.

Other interesting resources and links

- Museum Hue

- Museum Detox

- University of Leicester, School of Museum Studies Diversity Scholarship

- UK Museums Association: “Museums Directors’ Report Outlines Targets for Improving Staff Diversity”

- Report: “Valuing Diversity: The Case for More Inclusive Museums”

- Video: “Working Class Heroes”, a session from the 2016 Museums Association Conference in Glasgow.

Posts on this blog that are of relevance:

- Punk Museology Project

- Knowing when to call it a day

- The Tomorrow People: Entry to the Museum Workforce

- Immaculate Integration

- Museum Workers Speak

If you know of any more projects or resources of interest, please feel free to submit them here.

Post link

Can child care workers afford child care? This chart maps the share of median preschool worker earnings required to pay for center-based child care by state.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ official affordability threshold for child care costs is 10 percent or less of a family’s income (Office of the President 2014). Typical preschool workers’ wages are not sufficient to meet that affordability standard anywhere. The share of their earnings going to center-based infant care ranges from 17 percent in Louisiana to 66 percent in D.C., as shown in Figure E. In 32 states and D.C., it takes more than one-third of total earnings to cover infant care costs. That means that a preschool worker’s entire pay in those states from January through at least April would be consumed by infant care costs.

Four-year-old care is slightly less expensive than infant care, primarily because of the lower teacher-to-child ratios. The National Association for the Education of Young Children recommends a 1:4 staffing ratio for infants, compared with a 1:10 ratio for 4-year-olds (CCAA 2013). Even so, when it comes to 4-year-old care, in no state are typical preschool or other child care workers’ earnings sufficient to meet the HHS 10 percent affordability standard. Child care costs range from 14 percent of total earnings in Louisiana to 52 percent of earnings in D.C., as shown in Figure F. A preschool teacher in D.C. would have to devote half her annual earnings to 4-year-old care.

![[For more analysis and commentary, please join me at robertreich.substack.com]The General Strike of [For more analysis and commentary, please join me at robertreich.substack.com]The General Strike of](https://64.media.tumblr.com/0eeb4e677804f05e9761c9b900b77d98/e271914fafacdb70-c2/s500x750/74b66ca6ee8274a7c3190a2de37566d8f0641c88.jpg)

![Ressources humaines [Human Resources] (Laurent Cantet - 1999) Ressources humaines [Human Resources] (Laurent Cantet - 1999)](https://64.media.tumblr.com/5976356d79dbc839b976f2886625c077/a8a72a3812bfd3ed-bc/s500x750/f0e6f6de3ff491dcf519ccad879ad22b02548a5f.jpg)

![Ressources humaines [Human Resources] (Laurent Cantet - 1999) Ressources humaines [Human Resources] (Laurent Cantet - 1999)](https://64.media.tumblr.com/9faaa9e548e6241f149326ad35b3c19f/a8a72a3812bfd3ed-36/s500x750/eabec6bdd506941e03cedfbf85942f6f62e3cd55.jpg)

![Ressources humaines [Human Resources] (Laurent Cantet - 1999) Ressources humaines [Human Resources] (Laurent Cantet - 1999)](https://64.media.tumblr.com/54c9d18cecfbe1c14ede73934cafed09/a8a72a3812bfd3ed-ba/s500x750/24ce29eb5d362e0ae92d067b102044f55b3082b3.jpg)

![Ressources humaines [Human Resources] (Laurent Cantet - 1999) Ressources humaines [Human Resources] (Laurent Cantet - 1999)](https://64.media.tumblr.com/48815841731def083cdb726742caf174/a8a72a3812bfd3ed-8e/s500x750/17c59959a83bbe8c8bd52f9113235939403dd3ef.jpg)

![Ressources humaines [Human Resources] (Laurent Cantet - 1999) Ressources humaines [Human Resources] (Laurent Cantet - 1999)](https://64.media.tumblr.com/9d4987c65f8549b0e63d6f2453e3cb88/a8a72a3812bfd3ed-81/s500x750/33452e22e5eb00cc806efc20b078f9f90b798e4c.jpg)

![Ressources humaines [Human Resources] (Laurent Cantet - 1999) Ressources humaines [Human Resources] (Laurent Cantet - 1999)](https://64.media.tumblr.com/39d08ef6c7d20b1c0772f2954fa5e81a/a8a72a3812bfd3ed-0a/s500x750/124123a769a78cf8b270fea9e5f62726c3724c4f.jpg)

![Ressources humaines [Human Resources] (Laurent Cantet - 1999) Ressources humaines [Human Resources] (Laurent Cantet - 1999)](https://64.media.tumblr.com/f1d7a6c811fa01774b0aa10d9412a6ba/a8a72a3812bfd3ed-52/s500x750/730fa3d852814e172e041c23495ccd990bf2a3a5.jpg)