#writing action

No really.

Taking the bullet out does nothing to help the person, and if your characters are in the field instead of a hospital, may actually cause more harm than good.

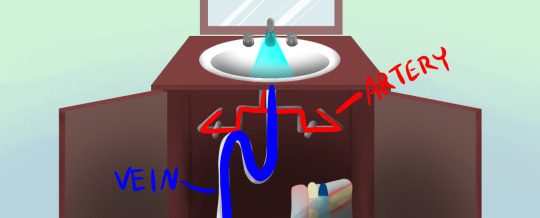

Imagine for a moment that you (for reasons unknown to all) decided to turn your sink on wide open, pick up a handgun, and shoot the pipes under your sink.

Maybe it hit the drain pipe, which would be bad, since all the water coming through the faucet is now dribbling out all over the floor. But even worse would be if it hit the water intake pipe, right? In that case, water under high pressure would be spraying everywhere!

Two bad options if you for some reason shoot your sink:

The vascular system of the human body is essentially one big set of pipes. The drain pipe? Those would be veins—under low pressure, but still very bad to leak from. The water intake pipe? Those would be the arteries—under high pressure and VERY dangerous to puncture.

But back to the sink example. Say you shot the pipes and hit the drain pipe (vein). Now there’s water pouring out onto the floor. Your roommate says “Quick! Wrap your hand around the pipe to hold the water in!” (“Put pressure on the wound!”) And you do! Water is still slipping out from under your hand, but it’s leaking a lot less than before! Right now, you COULD find some duct tape (bandages) and secure the pipe further so you don’t have to keep holding it.

Instead, however, you say to your roommate: “Hold on! I’ve got to find the bullet!” You let go of the pipe (stop putting pressure on the wound) to dig around in the cabinet (body) for the bullet. Seconds, maybe even minutes pass, and that pipe is freely gushing out water the whole time.

Finally, you find it! You pry the bullet out of the wood, hold it up to your roommate, and drop it in a little metal dish with a ‘clink’.

“Job well done,” you tell yourself. “We’re out of the woods now.”

Except that, you know, the pipe is still damaged and gushing water out onto the floor, and the bullet wasn’t actually doing anything harmful inside the cabinet. Also, while you were rummaging around for little Houdini, you weren’t putting pressure on the pipe, so that sink (patient) lost a whole lot of water (blood) that it didn’t need to. Can you imagine how much more it would have been if you’d hit the water intake pipe (artery) instead?

I know what you’re thinking. “But in movies—!!” And I know. But here’s the thing: Hollywood? It’s a bouquet of lies. I’m sorry. I really am.

In fact, even that distinctly bullet-shaped thing you usually see pulled out of people in movies may not always be true. Many times the bullet mushrooms out or becomes malformed. Depending on what that bullet ran into (like bone) it might have even broken into a dozen pieces. Try digging those out of your protagonist!

Now sometimes, but not always, doctors WILL remove the bullet (or fragments of bullet). For example, if they’ve already got the patient in surgery, and AFTER they’ve already repaired any veins, arteries, and organs to the best of their ability. Or if the patient doesn’t need surgery (if it didn’t hit anything major and is just lodged in the muscle or fat) but doctors notice that the bullet or fragment is likely to cause damage if left inside the patient.

More often than not, however, the bullet isn’t doing anything actively damaging while inside the patient, or the removal of the bullet would be more dangerous than leaving it where it is. This is why most bullets don’t get removed at all.

This is true if your characters are at a hospital, but ESPECIALLY if this is a field job. If trained physicians with all the tools at their disposal, blood transfusions, and a sterile environment most likely won’t take the bullet out, then Dave McSide-Character should DEFINITELY not be sticking his filthy, 5-straight-chapters-of-parkour fingers or his I-just-stabbed-a-guy-but-I-wiped-the-blood-off-on-my-pants knife inside the protagonist to fish around for some bullet that isn’t even causing harm. The recommended way to deal with a gunshot wound in the field? Pack it with gauze (or yes, even a filthy we’ve-been-on-the-run-for-two-weeks-in-the-same-clothes t-shirt if that’s all you have. Wound infection is a different post) and keep constant pressure on it.

Remember: stopping the leak in the sink is the most important thing. Not rummaging around in the cabinet for the bullet. Taking it out does literally nothing.

Two perfectly realistic reasons why you might have a character take the bullet out:

Now, sometimes, depending on the characters or the world you’re writing in, this might be different. In some instances, you might want to write the lead-scavenger-hunt scene in!

The first reason is if they just don’t know

And that’s really important when writing realistically. Not everyone is a professional in emergency wound care. Most people get all their knowledge of emergency medicine from Grey’s Anatomy and House M.D.

- If your character has any medical training? Probably don’t do it

- If your character has any military or police training? Some know, some don’t, so writing it either way is believable. It’s a toss-up, but they DO have more experience with gunshot wounds (either personally, witnessed, or in training videos and word of mouth)

- If your character is a 17-year-old art student who saw blood for the very first time two chapters ago? Well now that character might just try digging for the bullet

And hey, maybe they’re like “I’m gonna get the bullet out!” but another character (the one who was shot, another character in the room, maybe even a 911 operator) steps in and says “No, no, no! Just put pressure on it!”

But regardless, injured characters in movies are always suddenly on the mend after the bullet is taken out. The vitals start to rise, they aren’t gasping for breath, their hand closes firmly around the love-interest’s hand, etc. And this doesn’t happen. Regardless of what your characterdoes, the rules of biology are still in play.

In the end, though, that bullet’s just minding its own business in there. The #1 priority is fixing the damage it caused on the way in.

The second reason is if the bullet is special

This is more for the SciFi/Fantasy writers.

If your character is a werewolf and was just shot by a silver bullet which is stopping their healing process and is slowly killing them? Yeah, take it out

If the bullet is actually some sort of tiny robot designed to burrow into their organs one by one? Yeah, take it out.

If the bullet had a spell or curse placed on it? Yeah, take it out.

If they need to get transported up to the med bay, but the bullet would cause some kind of issue with the transporters? Yeah, take it out.

But in all of these examples, the bullet has to be inherently dangerous. For normal humans with normal bullets, its just a hunk of lead.

Hope this helped some of you action writers out there!

Good luck and good writing!

Disclaimer: In the event that you or someone you know has been shot, the best thing to do for them is call for an ambulance and follow the instructions provided by the operator. This post is intended to give accurate writing advice to authors and script writers, but I am not a medical professional. While I do believe that the research that I’ve done on this topic is factually accurate, it should not be taken as actual medical advice.

Post link

You may have heard the common writing craft advice: Act first, explain later.

This doesn’t work out when you’re pouring your fifth glass of wine and drunk-texting a confession to BFF about eating the last bag of Cheetos your husband had been pining for (I would never!).

But it’s great if you’re giving a story beginning or a scene instant momentum, engaging readers to follow something exciting, and showing how a character reacts or makes decisions under pressure.

This cuts through that propensity to start a scene with telling and backstory and that slow setup that’s hard to shake off. And if you’re struggling to start a scene, sometimes jumping right into the action helps to get the writing gears oiled, too.

But the common pitfall with this common advice is: confusing the heck out of readers.

Suppose we have a bank robbery that bursts off of page one, ninjas in black masks yelling and shooting the ceiling, customers and employees screaming. Then one baddie ninja drags a pale, trembling employee to unlock the big safe, his gun barrel jutting painfully into the woman’s back. She sobs and obeys his orders. Once he has the cash, police arrive outside the bank, their car lights flashing wildly, increasing the stress of the moment. While police and Baddie Ninja Leader end up in a hostage negotiation, a wizard floats down into the bank and the ninjas fight him. Then, a news helicopter hovering near the rooftop explodes, a tumbling cloud of scrap metal, fire, and ash snowball into the heart of the city.

After pages and pages of this scene unfolding, we have no idea what’s going on or who to care about.

We’re getting thrown into another world and trying to make sense of our surroundings. But it’s not as pleasant as a thumped landing in a TARDIS from a Doctor Who episode. It’s more like utter confusion and impatience in that example I just sneezed out, where we’re trying to anchor ourselves to something but can’t.

Sooner (rather than later), readers need to…

- understand what’s happening in context

- connect with a character

This is where we trip. And if you’re like me, crash without grace.

We can choose not to reveal certain story details yet (that’s the “explain later” part), but we need to make sense of what we do share and introduce a character that readers want to follow, whether it’s caring about them or hating them.

One example I love is from 1987, the very first lines of Nora Robert’s Hot Ice:

“He was running for his life. And it wasn’t the first time. As he raced by Tiffany’s elegant window display he hoped it wouldn’t be his last. The night was cool with April rain slick on the streets and sidewalk. There was a breeze that even in Manhattan tasted pleasantly of spring. He was sweating. They were too damn close. Fifth Avenue was quiet, even sedate at this time of night. Streetlights intermittently broke the darkness; traffic was light. It wasn’t the place to lose yourself in a crowd. As he ran by Fifty-third, he considered ducking down into the subway below the Tishman Building—but if they saw him go in, he might not come back out.”

The main character is deep in action while Roberts describes the setting and why the character needs to run—he’s afraid for his life. We just don’t know yet what the baddie wants from him. But we’re starting to get curious and to care what happens to this protagonist as his options for escape narrow.

Suddenly, act first, explain later becomes an umbrella for including other writing rules:

Anchoring the fictional world: details that establish the setting and orient readers. This includes the rules of the world.

“Fifth Avenue was quiet, even sedate at this time of night. Streetlights intermittently broke the darkness; traffic was light. It wasn’t the place to lose yourself in a crowd.”

Character sympathy and goals: the character is trying to get something or, in this case, get away from something that threatens his world.

“He was running for his life.”

Bites of info: creating context—embedding background info or explaining the relevance—between the action. In this case, hinting that this protagonist isn’t the perfect citizen.

"And it wasn’t the first time.”

After that thrilling action, we can slow down to give readers more insight: why he’s being chased, why she doesn’t trust men, why he doesn’t talk to his father anymore, etc.

It’s all about orchestrating a particular experience for readers—from action that’s exciting and makes sense so readers get hooked, to explaining the truth later so readers stick around until The End.

Only you, the author, can do this. And if you need a little help, I’m here for you.