#archivists

After a brief hiatus we are starting up our Tumblr account again.

Is this thing on?

Do people still use Tumblr?

What would you like to see from us? Featured artists spotlights? Available artists books and zines on our webstore? Events / Workshops / Exhibitions Calendar? All of the above? Let us know by reaching out via direct message.

Need a reminder of who we are:

Founded in 1999, Booklyn is an artist-run, non-profit 501 © (3), consensus-governed, artists and bookmakers organization headquartered at the Brooklyn Army Terminal in Sunset Park, Brooklyn.

Booklyn supports artists and organizations committed to environmental and social justice. We work towards this by documenting, exhibiting, promoting, and distributing their work within educational institutions worldwide. We envision a world in which art and bookmaking are tools for education, personal agency, community engagement, and political activism.

Visit our website for more information and stay tuned…

When your poster-sized archival supplies come wrapped in bubble wrap…

Betty Ford * First Momma * 1970s * First Lady * What tags do you see?

We’re continuing our celebration of Betty Ford’s Centennial by tagging photos of her in the National Archives Catalog. Tagging photos is a fun and easy way to help make records more searchable and discoverable. By adding keywords, terms, and labels to photographs, you help identify and categorize records of Betty Ford based on different topics about her life.

New to the National Archives Citizen Archivist program? It’s easy to register and get started. Check out our Resources page where you can learn How to Tag and Transcribe Records, and What Makes A Good Tag. Already have a National Archives Catalog account? Start Tagging! http://bit.ly/BettyFordTagging

Image: On a Campaign Trip in Texas First Lady Betty Ford, aka “First Momma,” Greets the Crowd Gathered at San Jacinto Battlefield Park for a Bicentennial Celebration, 4/21/1976. @fordlibrarymuseum

Post link

President Roosevelt himself took this photograph of Daisy Suckley in the White House as she went through various papers, February 10, 1942. (Photo: FDR Presidential Library & Museum)

This post was written by Keith Muchowski, an Instruction/Reference Librarian at New York City College of Technology (CUNY) in Brooklyn, New York. He blogs at thestrawfoot.com.

Margaret Suckley was an archivist at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library in Hyde Park, New York from 1941 to 1963. But she was much more than that.

“Daisy” Suckley, as she was known to friends and family, was born in Rhinebeck, New York in 1891 and grew up on Wilderstein, the family estate on the Hudson River not far from the Roosevelts’ own Springwood in Hyde Park. This was a small, rarefied world and in the ensuing decades Daisy saw sixth cousin Franklin’s rise to prominence. She eventually became one of his closest friends and confidants, sharing the good times and the bad with the country’s only four-term president. Ms. Suckley was there for Franklin in the 1920s when he was struck paralyzed from the waist down with polio, knew him during his years in Albany when he was New York governor and he became a national figure, attended the presidential inaugural in 1933 in the depths of the Great Depression, offered a discreet and comforting ear during the dark days of the Second World War when, as commander-in-chief, he made difficult and lonely decisions affecting the lives of millions around the world. Finally, Daisy was one of the inner circle present in Warm Springs, Georgia when the president died in April 1945. Roosevelt was inscrutable to most—some called him The Sphinx—but if anyone outside his immediate family knew him, it was Margaret “Daisy” Suckley.

Ms. Suckley (left) in Roosevelt’s private office at the presidential library with actress Evelyn Keyes, and Library Director Fred Shipman. Ms. Keyes is holding the album-version of Ms. Suckley’s book The True Story of Fala, October 31, 1946. (Photo: FDR Presidential Library & Museum)

There were perks to being Roosevelt’s close friend. The two enjoyed picnics and country drives. Both loved to dish the gossip about Washington politicos and the Hudson River Valley families they had known for decades. Daisy helped President Roosevelt design his Hyde Park retreat, Top Cottage. She enjoyed the “Children’s Hour” afternoon breaks when Roosevelt would mix cocktails for himself and his friends to unwind. There were getaways at Shangri-La, the rustic presidential retreat in Maryland’s Catoctin Mountains known today as Camp David. She attended services at Hyde Park Church with the First Family, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth when the royals visited in 1939. It was she who gave him Fala, the Scottish Terrier to whom he was so attached after receiving the pooch as a Christmas gift in 1941.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt stood at a podium on the grounds of his family home in Hyde Park and dedicated the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library on June 30, 1941. He was still in office at the time, having won re-election to an unprecedented third (and eventually fourth) term seven months previously. Roosevelt clearly believed that libraries and archives were themselves exercises in democracy in these years when fascism was spreading around the world. Ever the optimist even as World War Two raged in Europe and the Pacific, Roosevelt declared “It seems to me that the dedication of a library is in itself an act of faith. To bring together the records of the past and to house them in buildings where they will be preserved for the use of men and women in the future, a Nation must believe in three things. It must believe in the past. It must believe in the future. It must, above all, believe in the capacity of its own people so to learn from the past that they can gain in judgment in creating their own future.” Then he quipped to the two thousand gathered about this being their one chance to see the place for free.

Roosevelt had been an unrepentant collector since his earliest boyhood days, with wide-ranging interests especially in naval history, models ships, taxidermy, philately, books on local history, political ephemera, and—probably above all—anything related to the Roosevelt clan itself. His eight-years-and-counting administration had already produced reams of material via the myriad alphabet soup New Deal agencies that had put millions of Americans to work during the Great Depression. It was becoming increasingly obvious in that Summer of 1941 that the United States would likely become entangled in the Second World War; as Roosevelt well understood, that would mean even more documents for the historical record.

Presidential repositories of various incarnations were not entirely new. George Washington had taken his papers with him back to Mount Vernon after his administration for organization. Rutherford B. Hayes, Herbert Hoover, and even Warren G. Harding had versions of them. Nora E. Cordingley (featured in a March 2018 Women of Library History post) was a librarian at Roosevelt House, essentially a de facto presidential library opened in 1923 at Theodore Roosevelt’s birthplace on Manhattan’s East 20th Street whose papers and other materials eventually moved to Harvard University’s Houghton and Widener Libraries. What was new about Franklin Roosevelt’s creation was its codification of what is today’s presidential library system. Roosevelt convened a committee of professional historians for advice and consultation, raised the private funds necessary to build the library and museum, urged Congress to pass the enabling legislation, involved leading archive and library authorities, and ultimately deeded the site to the American people via the National Archives, which itself he had signed into being in 1934.

The academic advisors, archivists, and library professionals at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library were all important, indeed crucial, to the professionalization and growth of both the Roosevelt site and what would become the National Archives and Records Administration’s Office of Presidential Libraries. However, Roosevelt understood in those early that he also needed someone within his museum and library who knew him deeply and understood the nuances of his life and long career. That is why he turned to Ms. Suckley, securing her a position as junior archivist in September 1941 just months after the opening. The library was very much a working place for the president, who kept an office there, where—unbeknownst to museum-goers on the other side of the wall—he might be going through papers with Daisy, entertaining dignitaries while she looked on, or even making decisions of consequence to the war. Ms. Suckley worked conscientiously, even lovingly, in the presidential library, going through boxes of photographs and identifying individuals, providing dates and place names that only she would know, filling in gaps in the historical record, sorting papers, and serving in ways only an intimate could. The work only expanded after President Roosevelt died and associates like Felix Frankfurter and others donated all or some of their own papers. The work also became more institutionalized and codified. Other Roosevelt aides took on increasingly important roles after the president’s death in 1945. More series of papers became available to scholars in the 1950s and 60s as the Roosevelt Era receded from current events into history. Through it all Daisy Suckley continued on for nearly two more decades until her retirement in 1963.

Margaret “Daisy” Suckley lived for twenty-eight more years after her retirement, turning her attention to the preservation of her ancestral home there on the Hudson but never forgetting Franklin. In those later years when reporters, historians, and the just plain curious curious showed up at Wilderstein and inevitably asked if there was any more to tell about her friendship with Franklin Roosevelt she always gave a wry smile and demure “No, of course there isn’t.” After her death at the age of ninety-nine in June 1991 however a trove of letters and diaries was found in an old suitcase hidden under her bed there at Wilderstein. A leading Roosevelt scholar edited and published a significant portion of the journals and correspondence in 1995 to great public interest. While it is still unclear if there was every any romantic involvement between Franklin and Daisy—as some have speculated for decades—the letters do provide a deeper, more nuanced portrayal of their relationship and show just how close the two were. Franklin Delano Roosevelt may have been The Sphinx to many, hiding his feelings behind a veneer of affability and bonhomie. To his old neighbor, distant cousin, discreet friend, loyal aid, and steadfast curator Margaret Suckley, he showed the truer, more vulnerable side of himself.

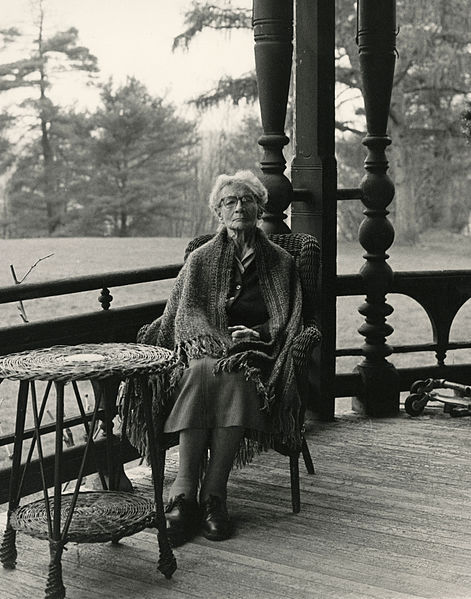

Ms. Suckley later in life at Wilderstein, 1988. (Photo: FDR Presidential Library & Museum)

Further reading:

Hufbauer, Benjamin. “The Roosevelt Presidential Library: A Shift in Commemoration.” American Studies, vol. 42, no. 3, Fall 2001, pp. 173–193.

Koch, Cynthia M. and Lynn A. Bassanese. “Roosevelt and His Library, Parts 1 & 2.” Prologue: Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration, vol. 33, no. 2, Summer 2001, Web.

McCoy, Donald R. “The Beginnings of the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library,” Prologue: The Journal of the National Archives, vol. 7, no. 3, Fall 1975, pp. 137-150.

Persico, Joseph E. Franklin & Lucy: President Roosevelt, Mrs. Rutherford, and the Other Remarkable Women in His Life. Random House, 2008.

Ward, Geoffrey C. Closest Companion: The Unknown Story of the Intimate Friendship between Franklin Roosevelt and Margaret Suckley. Houghton Mifflin, 1995.

This post was written by Keith Muchowski, who is an Instruction/Reference Librarian at the Ursula C. Schwerin Library, New York City College of Technology (CUNY), in Brooklyn, NY. He blogs at thestrawfoot.com. Keith also provided the image above of Nora E. Cordingley’s 1931 naturalization card.

Nora E. Cordingley died on March 14, 1951. The name may not be familiar, but Ms. Cordingley was active for three decades in one of the most significant projects in presidential librarianship: the collection, preservation and dissemination of the letters, papers, and hundreds of thousands of other items related to the short, strenuous life of Theodore Roosevelt. When the twenty-sixth president died on January 6, 1919, his family, friends, and close associates formed the Roosevelt Memorial and Woman’s Roosevelt Memorial Associations. One of the first moves of the RMA and WRMA was purchasing the East 20th Street site upon which Theodore Roosevelt was born in 1858, and where he lived until his early teens. The groups also bought the neighboring lot where young Theodore’s uncle, Robert B. Roosevelt, resided. Roosevelt House, as it was originally called, opened to great fanfare on October 27, 1923, what would have been Theodore Roosevelt’s sixty-fifth birthday. The institution had two missions: to be a museum & library and to serve as something of a center for American Studies. Ironically however one of Roosevelt House’s most important players in these years was not American, but Canadian: Nora Evelyn Cordingley.

Ms. Cordingley was born in Brockville, Ontario on January 23, 1888. She came to New York City to attend Queens College, from which she seems to have graduated around 1910. Cordingley was a student in the first class of the Library School of The New York Public Library in 1911. The NYPL’s new initiative was not a library program as we know it today, but more a vehicle to train para-professionals who would go on to work in various support services. (The New York Public Library program lasted fifteen years. It was merged along with the New York State School at Albany to become part of Columbia University’s new School of Library Service.) Somewhere in these years—the chronological record is unclear—Cordingley, her parents, and her sister settled in Tuckahoe just north of New York City in Westchester County. Cordingley worked as an assistant in the library of the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. The work was probably unrewarding, but in all likelihood it was through this position that she got her break, for it happened to be at the Metropolitan Life Tower at 1 Madison Avenue and 23rd Street that the Roosevelt Memorial Association opened its headquarters in 1919. It was there in 1921 that the RMA offered Ms. Cordingley a job as a cataloger with the Bureau of Roosevelt Research and Information.

Memorial officials had been collecting material even in these years before the House opened in 1923. By 1921, the year she hired on, the RMA had gathered nearly 15,000 individual items. The items were as disparate as the life they represented and included many of the over 100,000 letters that Roosevelt penned, various editions of the nearly three dozen books he authored, positive and negative political cartoons that captured his unique physical bearing and caricaturist’s dream of a visage, scrapbooks, political campaign ephemera, speeches, a vast film archive, and much more. One must remember that this was something of a new and original enterprise; presidential libraries did not exist at tis time and would not for another two decades when another Roosevelt, Franklin D., created the first one at his home in Hyde Park. The Theodore Roosevelt Collection only grew after the opening of the house in 1923. Assessing the RMA’s work in 1929, a decade after its founding, Director Hermann Hagedorn told an audience at the American Library Association conference in Washington D.C. that a New York Public Library official had informed him that Bureau of Roosevelt Research and Information was the largest library dedicated to one individual in the United States. The work continued into the 1930s. Meanwhile, Ms. Cordingley became became a naturalized American in 1931. In 1933-34 she served as chairperson of Museums, Arts & Humanities Division of the Special Libraries Association.

After twenty years on East 20th Street the Roosevelt Collection moved to Harvard’s Widener Library in 1943. When the collection relocated, so did Ms. Cordingley. She moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts and continued her work. She gave an address on the rarities within the collection at the Bibliographical Society of America conference in January 1945. One of her many projects in these years included assisting with the organization and eventual publication of Roosevelt’s correspondence. Starting in 1948, the Harvard Library, Roosevelt Memorial Association and Massachusetts Institute of Technology began a project to edit and annotate Theodore Roosevelt’s 150,000 letters. Harvard University Press published volumes one and two of The Letters of Theodore Roosevelt in April 1951. These were the first installments of what would eventually be an eight volume undertaking. About 10% of Roosevelt’s total output—nearly 15,000 some odd letters—were eventually published in the set over the next several years. Sadly, Nora was not there to see any of it. Nora Evelyn Cordingley died of a heart attack in her office in Harvard’s Widener Library on March 14, 1951.

Bibliography:

Cordingley, Nora E. “Extreme Rarities in the Published Works of Theodore Roosevelt.” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, vol. 39, no. 1, 1945, pp. 20-50.

Hagedorn, Hermann. “Building Up the Roosevelt Memorial Collection.” Bulletin of the American Library Association, vol. 23, no. 8, 1929, pp. 252–254.

Roosevelt Memorial Association: A Report of Its Activities, 1919-1921, Roosevelt Memorial Association, New York, 1921.

Today’s submission is by Christopher A. Brown, Special Collections Curator for the Children’s Literature Research Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia. The image of Mrs. Field is courtesy of the Children’s Literature Research Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia.

It’s impossible to think of the field of children’s librarianship without thinking of Carolyn Wicker Field. Mrs. Field (as she is still known at the Free Library of Philadelphia) was a driving force across the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania as well nationally. In her 30-plus year career, Mrs. Field headed the Office of Work with Children and oversaw the creation of the Children’s Literature Research Collection, the second largest repository of children’s literature, original artwork, manuscripts, and ephemera in the nation. Field’s passion for the promotion of children’s literature was unquenchable; she served as the president of the Children’s Division of the American Library Association (now known as the Association for Library Service to Children) and the Pennsylvania Library Association. From 1958-1960, Mrs. Field was a member of the Newbery-Caldecott Medal Selection Committee and chaired the committee in 1958.

Carolyn Field published several books on children’s literature, including Subject Collections in Children’s Literature,a catalogue of the special collections of children’s literature housed in the United States, and Values in Selected Children’s Books of Fiction and Fantasy,an exploration and bibliography of over 700 fiction and fantasy titles, co-authored with Jacqueline Shachter Weiss. Field was also an editorial advisor for, That’s Me! That’s You! That’s Us! A Bibliography of Multicultural Books for Children.

Mrs. Field was honored with numerous awards throughout her lifetime. In 1963, she was awarded the Scholastic Library Publishing Award. In 1974, she was named a Distinguished Daughter of Pennsylvania, an award given to Pennsylvania women whose accomplishments have state or national importance. In 1994, Mrs. Field was the recipient of the Association for Library Service to Children’s Distinguished Service Award, and in 1996 she was the first recipient of the Catholic Library Association’s Mary A. Grant Award for outstanding volunteer service. She was honored by the Pennsylvania Library Association in 1984 when the Youth Services Division named an award in her honor. The Carolyn W. Field Award is presented annually to a Pennsylvania children’s author or illustrator.

Carolyn Wicker Field died from congestive heart failure in Philadelphia on July 24, 2010. A copy of her favorite quote by Walter de la Mare still hangs in the Children’s Literature Research Collection: “Only the rarest kind of best in anything can be good enough for the young.” It is a philosophy that is still firmly embraced at the Free Library of Philadelphia.

historicity-was-already-taken:

I’m a petty person in a lot of ways, and I’ve held a grudge against the AHA (American Historical Association) since that time in 2014 when they brought me in for an interview, kept me an hour longer than scheduled because they loved my ideas, and then hired someone 100% less qualified than me and stole my ideas.

BUT ohhoho this takes the cake. The relationship between (tenured) historians and archivists was already messy enough (immense individual and structural disrespect on one end, with reflexive anti-intellectualism and resentment on the other, for starters), but then some genius at the AHA literally sat down and penned this open letter to NARA (the US National Archives and Record Administration), showing all of us exactly how much respect they have for the work, safety, work/life balance, and, frankly, pay-scale of archival professionals NOT TO MENTION how many archivists lost their damn jobs since March 2020.thx to @archivesandfeminism for posting about this on fb

“August 2, 2021

Dear Mr. Bosanko,

The American Historical Association (AHA) is writing to express concerns regarding the National Archives and Records Administration’s planned research room capacity across its facilities, including presidential libraries, as the agency begins to reopen following pandemic closures.

Potential high demand for archival research, combined with NARA’s limited capacity, is likely to result in frustration for researchers. With historians eager to resume research for dissertations, books, articles, and other projects that have been put on hold due to the pandemic, many have begun to plan research trips, particularly to NARA I and II. The AHA has been fielding many questions about the reopening, and historians have raised questions and concerns about NARA’s plans.

We recognize the strain the pandemic has placed on NARA staff and the difficulties of operating facilities around the country during a pandemic in which conditions remain fluid and the health and safety of staff are paramount. Reopening reading rooms amidst fluid health conditions at the same time that staff provide pandemic-initiated research assistance tasks and digitization initiatives both remotely and on-site create competing demands for the time and attention of NARA’s staff.

In such a changing environment, exacerbated by varied conditions across the nation, we write to seek clarity as to NARA’s plans and to offer our help in communicating with the community of history researchers. The AHA would be glad to assist our colleagues at NARA in managing the expectations of a likely surge of researchers in terms of advocacy, messaging, or in other ways.

In consultation with history researchers and other history organizations, including the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations and the State Department Historical Advisory Committee, we have developed the following list of questions and concerns for your consideration as reopening plans continue to develop:

1) What measures are in place or in development to accommodate a potential surge of researchers when current restrictions are lifted entirely?

2) We understand and expect that restrictions will be lifted in increments, depending on local public health conditions. Will any pandemic-related requirements become permanent? We hope these requirements are indeed temporary and that we will be notified if plans change in this regard.

3) Might NARA institute a process within the contours of federal regulations that maximizes equitable access for NARA’s various constituencies? Some researchers have specific limitations as to time and material resources to complete their research. Travel distances also differ among individuals and categories of researchers.

4) We encourage NARA to revise upward the limits on the number of boxes that a researcher can access at one time, particularly those traveling long distances domestically or internationally with restricted time to spend. Does NARA plan to modify or otherwise revise its plans according to the most current data available from OCLC’s REopening Archives, Libraries, and Museums Project (REALM)?

5) Does NARA maintain metrics on average usage of its research rooms? Can this information be shared with the public? Would it be helpful for scholarly organizations to survey their members regarding the timing of their planned research trips?

6) How have the closures of NARA facilities during the pandemic affected the digitization program overall?

7) Does NARA possess the infrastructure to accommodate digital facsimiles of records created by researchers, and the ability to collect such facsimiles? Might the historical community help in this effort as part of a community-driven initiative that would work in tandem with NARA’s systematic ones?

8) Has NARA examined the possibilities of extending research room hours to include evenings and weekends, as pandemic conditions and federal personnel policies allow? At a minimum, can all the facilities be opened on Saturdays?

9) Is it possible to temporarily redeploy, perhaps with additional training, personnel from other NARA departments and/or to rehire retired NARA personnel to staff research rooms, according to magnitude of research interest?

10) Given the situation, we would expect an increase in research queries, given the uncertainties of the current moment. Does NARA have sufficient staff to respond promptly and thoroughly to researchers’ queries? Can the process of responding to queries be made more efficient?

11) What can the scholarly community do to assist NARA as it reopens its research rooms to onsite research in terms of advocacy, messaging, or anything else?

12) Does the federal budget process provide any opportunities for NARA to request supplementary funds for the above purposes? Can scholarly organizations and the community provide support for soliciting additional resources?The questions we have posed are by no means exhaustive. Our members and other researchers have additional concerns not covered here. It is in NARA’s interest, and ours, for users to have easy and clear access to facts. Is it possible for NARA to establish some mechanism by which users can pose questions directly about reopening and receive informed responses?

The AHA encourages NARA to serve as many people as possible within the limitations of current conditions to protect the health and safety of staff, recognizing that there will inevitably be issues of equitable access based on proximity to the archives. We strongly encourage NARA to do everything possible to mitigate these disparities and to be as transparent as possible about current policies and regulations to manage researchers’ expectations, especially those who must travel long distances to conduct research.

The AHA is eager to assist NARA in communicating with the community of history researchers and in any other way that would be useful. We also stand prepared to add new items and arguments to our recently increased level of advocacy for NARA in the federal budget process.”

TL:DR; OUR BOOKS AND THESES ARE MORE IMPORTANT THAT YOUR SALARIES AND LIVES :D :D

I have been SO MAD about this.

I didn’t take a 7 person (80%) personnel reduction in my department for this level of disrespect.

I love (read: hate) the implication that we’ve done nothing but twiddle our thumbs all pandemic when I know so many of us have bent over backwards to try and accommodate this for (usually very kind) patrons.

Also lol @ rehiring retired folks or hiring more staff, many of us were furloughed or straight up laid off, nobody has the budget to hire *additional* people.

If you don’t work in libraries or archives, this is the culmination of YEARS of us being told to Do More With Less combined with “Can’t you just…”

If you have ever worked customer service, you know it. Can’t you just give me the discount, can’t you just make the exception, can’t you just…

This is after every institution saw their staff shrink, their budgets shrink, their own work scope grow, and bust their ass during a global pandemic while we scrambled to do whatever we could and in a way that was safe. We’ve all had millions of meeting about how to do as much as possible for researchers while keeping staff safe. I promise, these “suggestions” have been discussed at length, we don’t need to hear them.

So this “can’t you just open because our research is more important than your safety” hit a nerve that was already really fucking raw.

While this open letter was directed at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) specifically, the fact is it hit a nerve with all archives staff (whether they have the degree or not) and probably all Library staff (or at least it should).

We are all underpaid. We have all gone through round after round of the Do More With Less requests, we are all understaffed. And that was the case before the pandemic. (Okay maybe a rare place wasn’t but that is the rare exception)

We, both libraries and archives, are in a field that has many more qualified people than jobs available. Let alone jobs that pay a livable wage, are full time, and/or permanent.

We have ALL had entitled researchers. We have all had gross researchers, people who were “above the rules” or would only listen to the top person, who have condescended and demeaned, who have made unreasonable demands. By no means all researchers, we have loads that we adore, but we have also had nightmare ones.

We want to help. We want you to use our resources. We have gone above and beyond for little to no recognition for a very very long time. According to the Office of Personnel Management (OPM, think HR for the federal government) morale at NARA is among the lowest in the entire federal workforce because of wave after wave of cuts, demands, and policy.

We. Are. Tired.

You want greater access? You want longer hours in reading rooms? You want more staff available for research and reference? You want more stuff available digitally? You want more/better equipment at our facilities? You want more?

ADVOCATE FOR MORE FUNDING.

It is that simple. Money might not solve every problem (it won’t make the pandemic go away) but boy howdy would it make one hell of a difference to almost all of your complaints/wishes.

Meet intern Maddi Brenner, third-year graduate student in the coordinated master’s degree program for Library and Information Science (MLIS) and Urban Studies (MS). She is in her final year of the program and plans to graduate in May 2022.

What is your area of study and research interests?

My research interests include urban history, public libraries, mental health & pedagogy, and anything archives.

Tell us about your thesis research and field work.

I am currently in the research phase of my thesis. I am analyzing the expansion of branch libraries and the implementation of a coordinated branch library system in the city of Milwaukee during the 1960s and 70s. I am reviewing the goals of the plan, its development and success post-construction. So far, I have noticed several discrepancies in funding and budget allocations, library location issues, council disagreements and neighborhood dynamics involved in library development.

I am also a fieldworker at Marquette University where I am processing the previously restricted collection of Joseph McCarthy (JRM). If you are interested in any random facts about the 1950s, I seem to have copious amounts of knowledge on the topic. One thing I am working on now is transferring relevant material related to and by Jean Kerr Minetti (the wife, and later widow, to Joe) from the JRM collection to its own open series. The documentation of women involved in the life of famous male figures is not often represented or even in its own narrative. The goal is to connect a sort of interrelatedness to the two series, but ultimately allow the individuals to stand alone in their interpretation.

It reminds me that although work has and is being done to address issues in collection arrangement and description, there is still more to do.

What draws you to the archives, special collections, or libraries profession?

I am really interested in how primary sources connect us to certain understandings of our history, especially through outreach, reference, and research.

What is your favorite collection within the archive – or most interesting record/collection that you’ve come across?

I don’t have a true favorite, but I do think it’s cool that we hold the Society of American Archivists records. It is a massive collection with over 350 boxes and more than 3,500 digital files. Organization of the material has been re-arranged multiple times with new accessions up to 2018. I am not only fascinated by the history of archiving and collection management, but also how these records shaped issues of privilege, representation, and accessibility in the archives today.

What are you working on now for the archives?

Currently, I am working on research regarding reference and WTMJ film footage. The purpose of the project is to explore the frequency of reference requests and the value of preserving WTMJ footage. I will be analyzing both social media and e-mail as platforms crucial in access and outreach processes.

I also regularly coordinate archive transfers to other Wisconsin schools. It is fun to see what type of material is out there from other repositories and how impactful this program can be for researchers. Wisconsin is one of the only states that has this program, so that’s exciting!

What’s something surprising you’ve learned (about yourself as an archivist or about the profession) since you’ve started working at UWM Archives?

Honestly, I’ve learned that no two days are the same at the archives. There is so much going on and almost always a reference inquiry - whether big or small that I can dive into. There is a common misconception that archivists just sit around in an underground storage room all day and though, I surprisingly love being in the storage rooms, that’s far from the truth. We wear many hats.