#childrens literature

We tend to think of grief and mourning as maladies of the mind, but the loss can grow and expand until it feels like more like a presence than an absence. In the poem “Death Barged In,” Kathleen Sheeder Bonanno describes her pain as a mysterious figure in a Russian greatcoat who barges in, slams the door, and now makes all her decisions for her:

Even as I sit here,

he stands behind me

clamping two

colossal hands on my shoulders

and bends down

and whispers to my neck,

From now on,

you write about me.

I read A Monster Calls by Patrick Ness and Last Night I Sang To The Monster by Benjamin Alire Sáenz back to back on a whim, only to find out that they have much more in common than just the word ‘monster’ in the title. Both are by incredibly talented young adult authors, both are about troubled families, and in both books, the loss these protagonists so desperately refuse to acknowledge takes on the physical form of a monster, looming over them.

Post link

When “Santa Claus” handed me a present at my father’s annual office

Christmas party, I could tell it was a book. Though books lack a

certain holiday pizzazz, I wasn’t disappointed because I spent most of

my free time with printed copy way too close to my eyes. It was when I

slipped off the wrapping paper that the disappointment came.

The book was titled A Girl From Yamhill and much thicker than what I

was used to reading. Though it was by Beverly Cleary, one of my

favorite authors (I routinely camped out in the sublime corner of the

library where her catalogue and Judy Blume’s collided), it was

subtitledA Memoir. I spent the rest of the party trying to ignore

the book and its butter-yellow cover, framing a black-and-white photo

of a 6-year-old Cleary in an organza party dress. When I accidentally

sat on it, I gave it the stink-eye.

Non-fiction meant schoolwork, the drying out and curing of facts until

nothing remained but a jerky to be gummed and swallowed. A memoir

would surely be the same, with the added torture of recounting the

boring life of someone my great-grandmother’s age.

On the car ride home from the party, I cracked open Yamhill, mostly so

my parents would think I liked the gift.

It begins with Cleary’s oldest memories, snapshots really—her mother

packing her farmer father’s lunch in a tobacco tin, young Beverly

dipping her hands in ink and going “pat-a-pat” all over a white damask

tablecloth.

On the second page, Cleary describes a chilly morning:

Suddenly bells begin to ring, the bells of Yamhill’s three churches

and the fire bell. Mother seizes my hand and begins to run, out of the

house, down the steps, across the muddy barnyard toward the barn where

my father is working. My short legs cannot keep up. I trip, stumble,

and fall, tearing holes in the knees of my long brown cotton

stockings, skinning my knees.

‘You must never, never forget this day as long as you live,’ Mother

tells me as Father comes running out of the barn to meet us.

Years later I asked Mother what was so important about that day when

all the bells in Yamhill rang, the day I was never to forget. She

looked at me in astonishment and said, ‘Why, that was the end of the

First World War.’ I was two years old at the time.

With that, I realized non-fiction wasn’t what I’d thought. Someone’s

life could be interesting, even the mundane parts–after all, wasn’t

that what I was reading about in Blume and Cleary’s fiction ventures?

Drama that was not rooted in mythology and heroic sagas (though they

had a place on my library wishlist too) but in the universal feeling

of inevitable change, in first periods, in fights with one’s mother,

in new schools and old friends, in the dubious mixture of excitement

and apprehension with which children view the future?

From there it was a short leap to realizing my life could be

interesting, if I was willing to observe and faithfully recount and

wasn’t too afraid or too bashful to share pieces of myself. Yamhill

spurred me to start keeping journals, a venture that I remember

largely as revolving around remembering what I ate for breakfast and

recording it. Though the journals were no great success, my worldview

had fundamentally shifted. Sure, no one was going to care about my

preference for Lucky Charms, but someday, I was going to write about

other things that happened to me and someone was going to read my work

and recognize something of herself.

Later in Yamhill, Cleary describes how a poor grade on a lavishly

descriptive essay turned her off from writing description for years.

In a lesson I unknowingly internalized for a very long time, criticism

wounded her but she never let it stop her from writing. I can’t say

for sure what Cleary’s stripped-down, no-nonsense style owes to that

early failure, but I like to think she exhumed the kernel of truth in

that criticism and used it to develop her economy with language, which

she employs like a released arrow: sharp, streamlined and always

focused on a single point.

I never particularly aspired to write “plain” or “to the point”

stories and essays, but several readers have told me they appreciate

those qualities in my work. I will admit to bristling at these

compliments before I remember that “plain” is a code word for writing

like Cleary’s: writing that trusts its story to be big enough,

meaningful enough (no matter how personal or quotidian, as women’s

stories are often labeled) to hook an audience without a sideshow of

technical fireworks.

Despite our rough introduction, A Girl From Yamhill now sits, or

rather, slumps, on my bookshelf with a broken spine, dog-eared pages

and all the other markers of a book well-loved. I have re-read it

regularly over the past 18 years to get another taste of

Depression-era Oregon, to laugh at young Beverly’s exploits and to

read about another woman who knew she wanted to tell her stories and

never wavered in her pursuit of that goal, despite the obstacles. I

will be forever grateful to Beverly Cleary for giving one skeptical

little girl that gift.

Meghan Williams is a writer living in Austin. Her writing,

primarily personal essays, has been featured on The Toast,The Hairpin

andArchipelago.

“A Caucus Race And A Long Tale,” illustration from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland by John Tenniel, 1865

Post link

While HP is far from being perfect, I think many of the problems with the series could be explained by the fact that it IS a series of kids books written 20-15 years ago, and probably wasn’t meant to be gone over with a fine-toothed comb years after the fact, that nobody knew at the beginning would have blown up the way it did. Both from story/plothole perspectives and from the perspective of certain things aging rather poorly in hindsight (sure 20 years isn’t a SUPER long time but there’s no denying that a lot of social change and increase in awareness has occurred in that time. This is not a defense of the author’s current antics but only the text within itself.)

Post link

Happy Read Across America Day!

The Great Birthday Bird has come from the land of Katroo to celebrate both Dr. Seuss’ birthday and Read Across America Day!

Theodor Seuss Geisel, better known as his pen-name Dr. Seuss, was born on March 2nd, 1904. His career in writing and drawing started in various advertising campaigns and magazines before making the switch to children’s books. His very first children’s book, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street was published in 1937 by Vanguard Press after it had been rejected by over twenty different publishers. He took a short break from children’s books during World War II to focus on political cartoons. He returned back to children’s book, this time under the publisher Random House, and continued publishing books that we continue to know and love today, like The Cat in the Hat (1957),How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (1957), and Green Eggs and Ham (1960).

Beginning in 1998, the National Education Association (NEA) began observing Read Across America Day every year on March 2nd. On this day, it is common for libraries, schools, and community centers to host special reading-related events to celebrate this day. Join us in reading your favorite Dr. Seuss book on Read Across America Day!

Happy birthday to you! by Dr. Seuss. New York : Random House, [1959]. SE. G27ha

And to think that I saw it on Mulberry street by Dr. Seuss. New York : Vanguard Press, 1937. SE. G27a

Post link

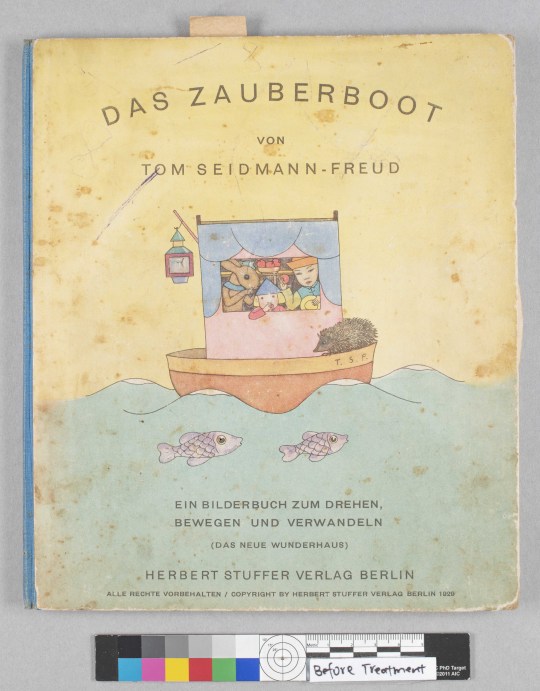

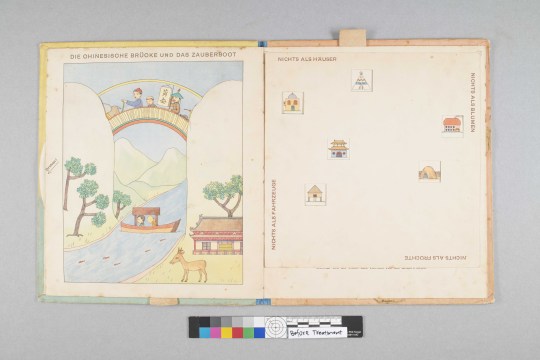

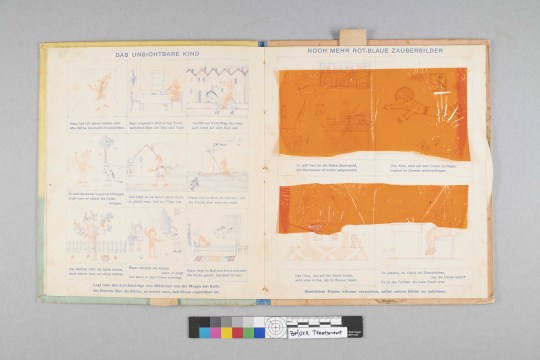

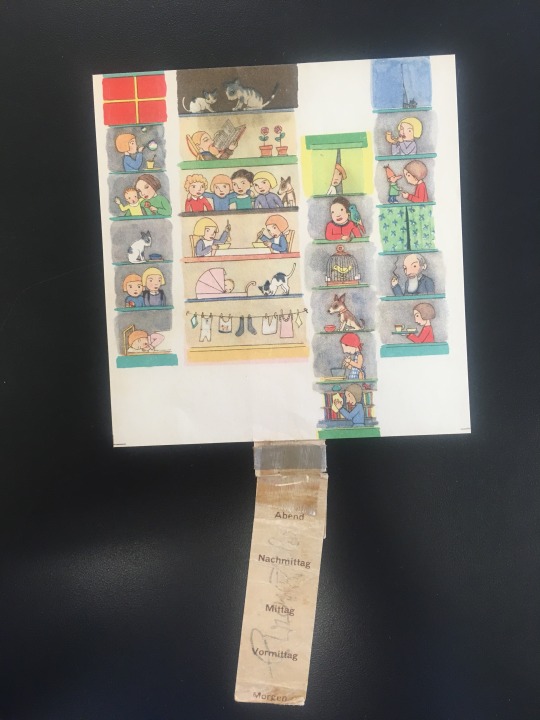

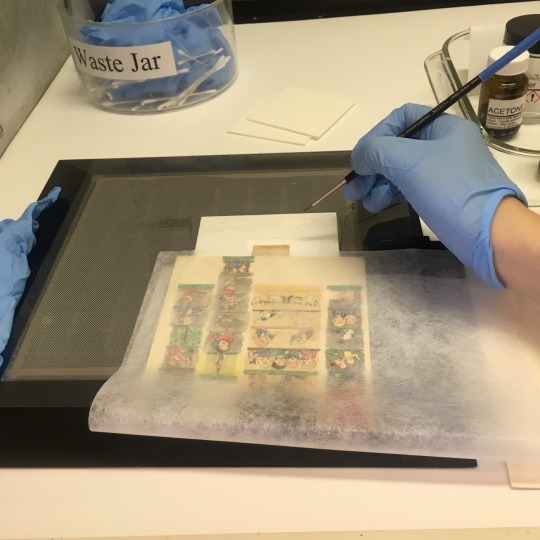

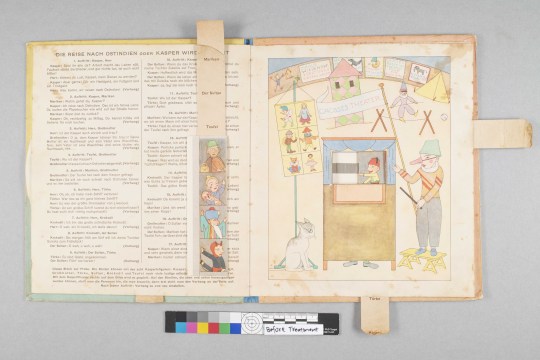

Second in a series of guest posts from Shaoyi Qian, summer 2021 Baker Fellow at the U-M Library’s conservation lab, describing her work on several pop-up and moveable books. Read more!

First in a series of guest posts from Shaoyi Qian, summer 2021 Baker Fellow at the U-M Library’s conservation lab, describing her work on several pop-up and moveable books. Read more!

Anyone else remember reading this in school?

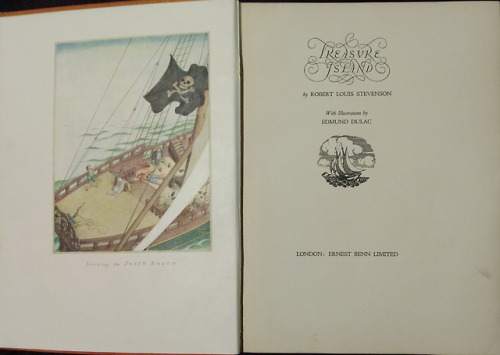

Happy Title Page Tuesday!

(Stevenson, R. L. (1927). Treasure Island. London, UK: Ernest Benn. Rare Book PR5486 1927)

Post link

Last up in our fall preview are two classics from our Children’s Collection, newly reissued as paperbacks in our NYRB Kids series.

Mary Chase, Loretta Mason Potts(September)

Ten-year-old Colin Mason is convinced he’s the smartest, best, and oldest kid in his family. Then, much to his horror, he discovers he’s not the eldest at all: he has a glum and gangly older sister, Loretta Mason Potts. Soon, Colin is secretly following Loretta down a hidden tunnel that leads from a bedroom closet to a whole other world—where she is mysteriously beloved by all, no matter how rude she is.

Eleanor Farjeon, The Little Bookroom(October)

This selection of twenty-seven favorite stories selected by Eleanor Farjeon herself are heartwarming and delightful. Inside you’ll find powerful—and sometimes exceedingly silly—monarchs, and commoners who are every bit their match; musicians and dancers who live for art rather than earthly reward; and a goldfish who wants to marry the moon.

There are a lot of reasons I was drawn to A Series of Unfortunate Events as a kid, and if I wanted to try and analyze them all I would have to write an entire anthology of books about the series and me and psychology and by the end of the day I would be very tired and you all would be very bored, so I’m not going to do that, but when I think about the series and probably the main reason why I’ve stuck with the series so long as a kid and now as a quasi-adult, what stands out to me is the beautiful way that Daniel Handler writes, portrays and deals with abuse.

There are a lot of messages that the series conveys across its thirteen volumes and even more in the companion pieces Handler has authored, but almost all of them come back to deal with abuse in some way, particularly child abuse. Even beyond just roundabout lessons that can be applied to child abuse, it actually depicts and deals with child abuse, a topic that is virtually nonexistent in middle grade literature even now as we start to become more aware of the topic. Children with harrowing backgrounds are common in the genre, but the difference between the Baudelaires and Harry Potter is that Snicket makes it very clear that what is happening to the Baudelaires is abuse and is wrong, whereas the Harry Potter series dismisses Harry being forced to live under the stairs as simply mean guardians and an abusive school teacher as a romantic pining for his lost love (don’t get me started on Snape discourse). A Series of Unfortunate Events tells children up front that abuse does happen and that that is what it is - abuse.

It showcases dozens of different varieties of abuse, physical, emotional, neglect, and it even hints at sexual with Olaf’s predatory behavior towards Violet. It shows different kinds of abusers, Mr. Poe, who does it out of genuine ignorance and an unwillingness to learn, and Count Olaf, who does it out of cruelty.

More than showing child abuse, it shows how people react to child abuse, either through internalizing it and believing that they are deserving of their fate, withdrawing from other people, or becoming distrusting of any and all adults to the point that they might miss out on people who could have possibly saved them if they had just trusted them. A Series of Unfortunate Events presents trauma in an accurate, non-sugar coated way to the audience that most needs to hear it.

As a seven year-old kid living with abusive parents, at the time I didn’t know why I loved A Series of Unfortunate Events so much, but I knew I loved it in a way I had never loved or related to a book before, and more than a decade later it still has a dramatic impact on my life. I was a cynic from a young age, and there’s something just draining about reading story after story of quick fixes and happy endings and stories where things go right when your life never seems to go right. I loved A Series of Unfortunate Events because the things that were happening to the Baudelaires, even though they took place in a fictional universe, were real. Handler never tried to pretend that life was great because it isn’t and if you’re a kid who has been taught by literature over and over that life is supposed to be great all the time and it’s great for everyone except you, that messes you up. A Series of Unfortunate Events told me it was okay to be messed up, and it told me that other people are messed up too, and the world is just as imperfect for everyone else as it was for me.

Esme Gigi Genevive Squalor would be a wonderful name for a chicken, not only because Esme’s personality perfectly embodies the sophisticated and self-absorbed air that all chickens have despite their extreme lack of intelligence, but also because the initials of Esme’s name spell out the word EGGS.

I’ve done my little analysis of the poem that Count Olaf recites just before he dies in The End, already, so I think it’s about time that I did analysis of the poem that Kit recites as well. Kit, as opposed to Olaf recites her poem in its entirety, but I’ve included the poem here as well just for convenience’s sake:

The night has a thousand eyes,

And the day but one;

Yet the light of the bright world dies,

With the dying sun.

The mind has a thousand eyes,

And the heart but one;

Yet the light of a whole life dies,

When love is done.

Kit reads her poem aloud first, and it’s a much less straightforward poem than the one that Count Olaf reads - it has a lot of symbolism and poetic language and the meaning isn’t stated directly within the text - but I think when it’s broken down it can be understood quite easily and it provides a great deal of insight into both her and Count Olaf, and the VFD as a whole as well.

The first thing a ASOUE fan will take note of in this poem, is obviously the eye connection. The passage immediately preceding this poem is of the Baudelaires’ reflections on the VFD eye and all the places they’ve seen it and all the people they’ve seen sport it and wondering whether the VFD is truly good or evil, so there’s definitely a point to be made about a poem about eyes coming directly after a passage about eyes, but I think in that obvious interpretation, readers often miss the subtlety of the poem.

Put quite simply, it’s a poem about not overthinking life and allowing yourself to be guided by your feelings. “The night has a thousand eyes” as opposed to the single eye (the sun) of the day, but the day is what is the brightest of them all and even the thousand eyes of the night sky do not come close to illuminating the world as well as the sun does. The mind likewise is capable of producing a million thoughts an hour, self-doubts, observations, second guesses, and it can be easy to be guided only by your head in this world and pick the rational over the emotional, but life only matters when you are happy - when you are guided by your heart. Rationality will always win in terms of quantity, but love is what lights up your world.

Although there is a break between when the original conversation occurs and when Kit recites the poem, it comes at the reunion of Kit and Olaf for the first time in assumingly a long time. Olaf kisses Kit, and says he would do that one last time, Kit says she’s not going to forgive him because one good act doesn’t make up for all he’s done wrong, and Olaf says that he doesn’t want forgiveness - he never apologized. Then Kit touches his tattoo.

The poem seems to be Kit’s response to Olaf’s tattoo and his experience with the VFD - perhaps both of their experiences, after all we know that Kit was instrumental in the murder of Olaf’s parents. She recites to him while reminding him of his lifetime bond of hatred to the VFD, that love is powerful and love is what makes life worth living, not all the regrets and hopes and alternate fantasies of a world we could have made. Olaf says he never apologized to Kit, and the Baudelaires, and he says it in a way that shows he has no desire to now. Olaf refuses to apologize for his actions because he feels they are rooted in vengeance. He is still mad at Kit and the Baudelaires for the harm they have caused him, either directly or indirectly, and in his own way grieving over the loss of his parents. He is angry that they were killed and that it could have been prevented and he is stuck in a mindset that demands retribution - but the thing about retribution is that it can never truly exist because there is no way to truly avenge your parents deaths as long as they are still dead. Olaf is stuck in his head imagining a fair world where none of this ever happens and he is so stuck in that mindset that he attempts to impose that justice onto the world in his own messed up ways. He loves Kit, it is clear, but he is so driven by anger that he does not let himself love her and does not let himself move on. He has fueled himself by anger and not love for so long that the light in his life has died and he is left a bitter, angry wreck of a man.

There’s a lot we can draw from this poem and this analysis of Count Olaf that Kit makes and a lot of it has to do with forgiveness and moving on from trauma. Count Olaf was never able to move on from his parent’s murder and in the end it destroyed him. He never forgave the people who hurt him and as a result he carried that weight and anger around with him until it destroyed him. This is not to say that people have an obligation to forgive their abusers, to love unconditionally and to let everything go, because there are some things you should hold onto and there is some anger that is justified, but anger is an emotion not a characteristic and is but one of a thousand little things in our lives that can distract us from what really matters in life. You can’t force yourself to live in the past because no matter how tightly you cling to it, it’s already gone and eventually you have to move on or everyone else is going to move on from you. The Baudelaires in the passage before this are so preoccupied by the thousand eyes that they’ve seen throughout their amazing adventures and interactions with the VFD and all the questions that they haven’t answered, that they temporarily lose sight of the one thing that matters. But in the end as they bring Kit’s baby into the world, and life begins anew, they forget their anger and their resentment towards all the injustice they are faced and towards the man who caused it all, laying dying behind them, alone and forgotten, they allow their hearts to guide them and they are unburdened by the past for the first time in a long time. Trauma is a healing process, but it is one that takes constant forward effort, and in this moment - in this crossroads where Olaf and the Baudelaires diverge for the last time - they chose to move on and accept that justice and answers aren’t always doled out evenly in the world and that sometimes you have to just let your heart guide you forward.

I’ve always loved the poem that Count Olaf recites to Kit just before he dies in The End, and by love of course, I mean I bawl my eyes out every single time I read it. He only reads the last stanza aloud, but here is the poem in its entirety:

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

They fill you with the faults they had

And add some extra, just for you.

But they were fucked up in their turn

By fools in old-style hats and coats,

Who half the time were soppy-stern

And half at one another’s throats.

Man hands on misery to man.

It deepens like a coastal shelf.

Get out as early as you can,

And don’t have any kids yourself.

- Philip Larkin

Obviously, we can understand why Handler didn’t want to include explicit profanity in a book written for middle grade children, but I really do love the fact that the first two stanzas are left unsaid and the reader, if interested actually has to go and research them and find them out for themself, because that is one of the points of the poem and one of the points of the series - that people don’t tell you the whole story and that things are always much more complicated than they seem - even things that seem like black and white morality are always so much more complicated.

Yes, your parents mess you up and ruin you, just like the Baudelaires find out in The Penultimate Peril and The End that their parents were not perfect and possibly even are the reason why all this horror has been happening to them, but the story is more complicated than that and the Baudelaires (and the readers) are left for themselves whether or not they want to leave it be - just read the last verse - or they want to explore for themselves and maybe not like what they find.

Ever since The Austere Academy, the Baudelaires have been told that the VFD was a noble organization and filled with volunteers that will help them, but the noble side of the VFD also produced lots of people who did horrible things: the Baudelaire parents, Jerome Squalor, Lemony and Kit Snicket. The VFD taught them to follow blindly and so they blindly followed and they accepted authority at its face value and as a result they became corrupted by those in power.

Ultimately, this poem is about the cycle of abuse and misery in this world. “Man hands misery onto man”, we inherit our trauma from each other and we create our own demons out of the demons that have been fed to us, and we tell ourselves that we won’t do the same, but we indubitably will. To be human is to be messed up, and the kindest thing you can do in life is to not bring any more people into the world.

But particularly interesting to me is Count Olaf’s recitation of the poem. Because in the passage, he’s not reciting it to to the Baudelaires, he’s reciting it to Kit, as she gives birth on a coastal shelf. On a personal, theoretical level, I have always used this as evidence that Beatrice II was Count Olaf’s biological daughter, but also it acts as a symbol of Count Olaf’s journey - he is an awful, awful man who has hurt the children put into his care time and time again and probably messed them up on some psychological level for the rest of their lives, but he too was messed up and turned out by the world by the people who raised and shaped him, and ultimately the root of evil goes back much further than we’d like to think. We’d like to think that Count Olaf is just a cruel, uncaring man who acts the way he does out of cold-blood, but the world doesn’t work that way and he’s trying to tell Kit that he is the way he is because of his history, that he was jaded by the world young and he never managed to escape, and that he’s not actually a bad man. But even as he recites the poem, he laughs, because he recognizes his complicity in everything - he has handed down his misery as well and he has brought a child into the world against all warning. It is him recognizing his crimes and his irony, something the Baudelaires and Kit never thought he would do.

It also serves a larger purpose in that Count Olaf has always been described as unintelligent and dismissive of intellect and reading and the orphans have always maintained that if a person is well-read they must be a good person and that reading is what makes people good. Because Count Olaf is not good, and yet he is able to recite an obscure poem - written by a librarian, no less - in the blink of an eye. Throughout the entirety of The End, Count Olaf has defied his stereotype by proving to be intelligent and capable of empathy and eschewing everything we thought we knew about him. Things are always more complicated than they seem and go back further than you’d like to think, and the world itself is a messed up place - a conundrum of esoterica, if you will - and defies any pithy explanation you might try and force upon it.

The End, the final book in the ASOUE series deviates substantially from the twelve previous books in the series because it doesn’t follow the traditional narrative that the other books adhere to at all. In the other books it always goes something like the orphans wind up in a new place, they meet someone they think can be an ally to them and then that person winds up either dying or being ineffectual or compromised in some sort of way by the arrival of Count Olaf and the orphans are forced to flee from danger, hoping along the way that eventually when all this is said and done they can find some nice quiet place to live, where they aren’t constantly in danger.

In The End, by contrast, they arrive with Count Olaf to a new location with people who are quick to eliminate Olaf as a danger for them and attempt to bring them into their peaceful happy lives. In actuality, the story could have ended there. They had no real reason to go against the rules of the island or question the authority of Ishmael, and none of the islanders or Ishmael were rude to them at all. The only reason they returned to Count Olaf and rebelled against the island is because they thought it was boring. After twelve books of adventure after adventure, trying to escape danger time and time again, the Baudelaire orphans realize that they actually don’t know how to exist in safety.

Which seems to defeat the entire point of the Baudelaire’s quest for safety in the other twelve books, but I think it’s an important point about what happens after the worst has already happened. The Baudelaires have reached safety after so long, but they’re so used to not being safe that they don’t even know how to be comfortable in a safe environment. They’ve wanted this for so long but once it finally came they realized that they were never prepared for it.

This is a common trope in the lives of people who have survived insurmountable trauma. They spend the duration of their trauma clinging to this hope of a better life outside of it and imagining a perfect world where they are safe all the time, but then when they escape they realize that they’ve become so used to their trauma world that the regular world seems completely foreign to them. Furthermore, once they’ve physically escaped their trauma they’re left with the second, more daunting task of emotionally escaping it and moving on.

The End isn’t an escape from danger in the traditional sense, but more a look into what we do once we have escaped danger and how danger eventually escapes us. Most books end when the danger has been resolved, the plot has been fulfilled and everything has been worked out. But ASOUE shows that even after the danger has been resolved, everything will never be worked out completely. Life isn’t a book with a simple exposition, climax and resolution, it is a series of unfortunate events and even after we’ve conquered our demons we still have to live knowing what happened to us and where and when and that antagonist is a much harder one to defeat.

One of the things the ASOUE series does particularly well is that it subverts the narrative that is all too often perpetrated in children’s literature (and adult literature, let’s be honest), that karma is a real operating force in the world and that we all are fated to have good or bad things happen to us depending on how well we act in the world. ASOUE shows that that is not at all true. Sometimes good things happen to good people and bad things happen to bad people - but it’s all random happenstance, and not some cosmic destiny for good people to be rewarded and bad people to be punished.

At the beginning of the series we get these three lovely, perfect children who as far as we know have done nothing wrong and are incredibly polite and kind even in the face of evil. Even though Snicket warns the audience that nothing good will happen to the orphans, kids know that good people always have happy endings so it’s brushed off as a depressing narrator who is simply describing the trials and tribulations that the Baudelaire orphans will face throughout the book. But when we get to the end and the orphans have solved the mystery, escaped from their captor and have proven themselves worthy of respect and a happy ending, they are defeated again through random happenstance and left more or less where they started. They have done nothing to deserve evil, but evil has been forced on them anyways.

One of the problems with perpetuating the idea that karma is an active force in the world is that if good people are always rewarded and bad people are always punished, then good people who consistently do good thing with no payoff are left feeling like they’re bad people because apparently if they were actually good they would receive some kind of retribution. But the world doesn’t work that way. Sometimes bad things happen to good people and good things happen to bad people and that’s just the way the world is.

A Series of Unfortunate Events does an incredibly good job of explaining the concept of a random universe - where things just happen and nothing really matters in the long run because everything will just turn out how it turns out regardless. It’s an absurdist (like happier nihilism) take on the world, and I find it interesting that such an obscure and defeatist philosophy is able to be introduced so easily to children as young as I was when I read the series. But then again, one of the things ASOUE does best is not being condescending to children and engaging with them about the real world - recognizing that they are smart, functioning beings capable of understanding the world - and teaching them such a hard lesson about life so early on without making it overly depressing is something that I rarely see talked about in praise of ASOUE, and something that I think is worthy of commendation.

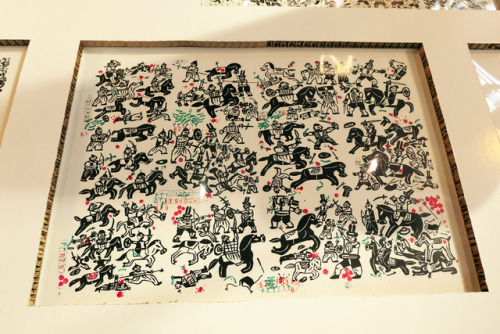

Bits and pieces of my current book project for Chinese publisher Dolphin Media. It’s children’s poems picture book!

Post link

This year I attendedBologna Children’s Book Fair from day one. In comparison to the last year when I arrived in the afternoon of day two, it was a big improvement. I also had differently focused appointments, made some new artists/publishers friends, and didn’t get food poisoning (thank you universe!) = Bologna Children’s Book Fair 2017 was a success!

Last year I had a lot of meetings with all kinds of publishers I admire, it was my first fair and I wanted to use it to the maximum. This year I only focused on those publishers who I believed were a good match for my work, something I learned from the previous experience. Since I’m in search of a European literary/illustration agent, I also had a couple of meetings at the agents’ centre.

Of course one of the highlights of the fair is seeing the illustrator’s exhibition. This year the artworks were arranged on tables (wouldn’t have been my choice for many reasons including bigger crowds, bad light reflection and general feeling of impracticality) but I still managed to take a good look at the artworks and took some pictures of my favourites. Unfortunately I forgot to write down the names of the authors (I’M REALLY SORRY :() The only author’s name I remember is Yara Kono (artwork with pink colour).

My friend Olya Ezova Denisova was part of the exhibition too! You can see her standing next to her work on the photo.

When I had some free time in between meetings, events and exploring the fair, I had a chance to meet up and chat with some new friends, illustrators and animators <3

This year I tried to tame my curiosity a bit and be more selective with what I spend my time on. I couldn’t resist sticking around Asian pavilions since Korean, Taiwanese and Japanese books are my favourite as well as more rare to spot in European bookshops. Other than that I was only visiting the stands of the publishers I already knew and liked.

After two full days I was completely exhausted and overwhelmed with new thoughts and reflections but since I was staying in Bologna for two more days I decided to attend the fair for one more day.

Other then the fair I also visited some cultural events in town including the opening of the exhibition of the children’s author and illustrator Beatrice Alemagna and another one of Isabelle Arsenault both of whom I really admire.I also managed to get an autograph from Beatrice (last photo <3)

That’s about it. See you next year Bologna <3

Post link

Some cute farm animals coming your way. This is book cover for learning text book I did for Scholastic inc.

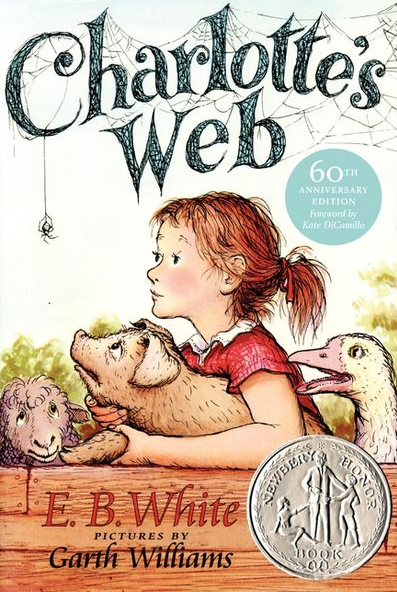

We’re thrilled to introduce #RememberReading, a new bookish podcast from HarperKids Books! Listen to the pilot episode with authors Jodi Kendall and Lisa Greenwald about the children’s classic, Charlotte’s Web!

Post link