#brain cells

with the school season starting up again i felt like a lot of us could use this

Brain Cell Transplants Are Being Tested Once Again For Parkinson’s

by Jon Hamilton / NPR Health

Researchers are working to revive a radical treatment for Parkinson’s disease.

The treatment involves transplanting healthy brain cells to replace cells killed off by the disease. It’s an approach that was tried decades ago and then set aside after disappointing results.

Now, groups in Europe, the U.S. and Asia are preparing to try again, using cells they believe are safer and more effective.

“There have been massive advances,” says Claire Henchcliffe, a neurologist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York. “I’m optimistic.”

“We are very optimistic about ability of [the new] cells to improve patients’ symptoms,” says Viviane Tabar, a neurosurgeon and stem cell biologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

Henchcliffe and Tabar joined several other prominent scientists to describe plans to revive brain cell transplants during a session Tuesday at the International Society for Stem Cell Research meeting in Boston.

Their upbeat message marks a dramatic turnaround for the approach.

During the 1980s and 1990s, researchers used cells taken directly from the brains of aborted fetuses to treat hundreds of Parkinson’s patients. The goal was to halt the disease.

Parkinson’s destroys brain cells that make a substance called dopamine. Without enough dopamine, nerve cells can’t communicate with muscles, and people can develop tremors, have difficulty walking and other symptoms.

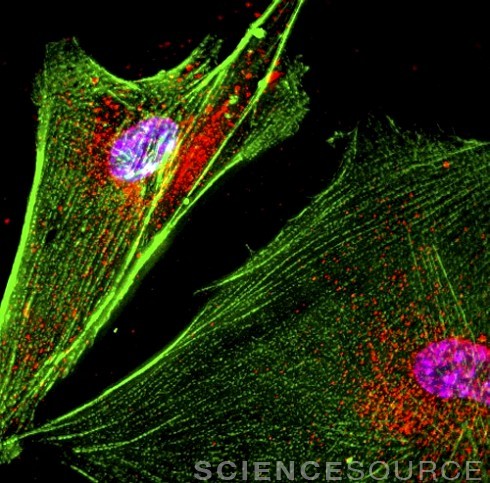

Image above © Roger J. Bick & Brian J. Poindexter / Science Source

Post link

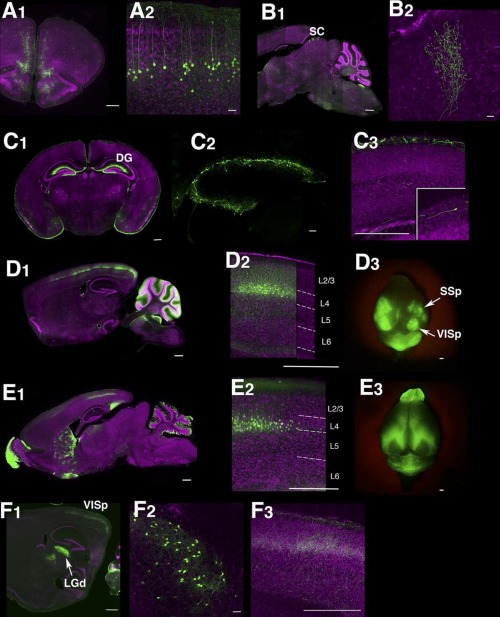

(Image caption: Lines labeling cortical subplate, mesencephalic, and diencephalic cell types (see Fig. 7 in Shima et al.))

Trapping individual cell types in the mouse brain

The complexity of the human brain depends upon the many thousands of individual types of nerve cells it contains. Even the much simpler mouse brain probably contains 10,000 or more different neuronal cell types. Brandeis scientists Yasu Shima, Sacha Nelson and colleagues report in the journal eLife on a new approach for genetically identifying and manipulating these cell types.

Cells in the brain have different functions and therefore express different genes. Important instructions for which genes to express, in which cell types, lie not only in the genes themselves, but in small pieces of DNA called enhancers found in the large spaces between genes. The Brandeis group has found a way to highjack these instructions to express other artificial genes in particular cell types in the mouse brain. Some of these artificially expressed genes (also called transgenes) simply make the cells fluorescent so they can be seen under the microscope. Other transgenes are master regulators that can be used to turn on or off any other gene of interest. This will allow scientists to activate or deactivate the cells to see how they alter behavior, or to study the function of specific genes by altering them only in some cell types without altering them everywhere in the body. In addition to developing the approach, the Brandeis group created a resource of over 150 strains of mice in which different brain cell types can be studied.

Post link

Call-and-response circuit tells neurons when to grow synapses

Brain cells called astrocytes play a key role in helping neurons develop and function properly, but there’s still a lot scientists don’t understand about how astrocytes perform these important jobs. Now, a team of scientists led by Associate Professor Nicola Allen has found one way that neurons and astrocytes work together to form healthy connections called synapses. This insight into normal astrocyte function could help scientists better understand disorders linked to problems with neuronal development, including autism spectrum disorders. The study was published in the journal eLife.

“We know that astrocytes could play a role in neurodevelopmental disorders, so we wanted to ask: How are they playing a role in typical development?” says Allen, a member of the Molecular Neurobiology Laboratory. “In order to better understand the disorders, we first have to understand what happens normally.”

Synapses form critical connections between neurons, allowing neurons to send signals and information throughout the body. Astrocyte cells play a role in synapse development by giving neurons directions, such as telling them when to start growing a synapse, when to stop, when to prune it back, and when to stabilize the connection.

Allen and her team took a closer look at how this process plays out in the visual cortex of the mouse brain. They sequenced the RNA of astrocytes at different stages of brain development to assess gene activity and compared it with neuronal synapse development. They found that astrocyte signaling was directly related to each stage of neuronal development. The researchers then wanted to know how the astrocytes knew to make these signals at the right time.

First, the researchers looked at what happened to the astrocytes when they changed the neurons’ activity. To do this, they stopped neurons from releasing a neurotransmitter called glutamate that can signal to astrocytes, and this stopped the astrocytes from showing the typical developmental changes. Next, the scientists stopped the astrocytes from responding to neurotransmitters, and found this stopped the astrocytes from expressing the right signals. With both these manipulations, the development of synapses was also disrupted, in line with the changes observed in the astrocytes.

Collectively, the findings suggest that astrocytes are responding to neurotransmitters produced by neurons to control the timing of when astrocytes produce signals to instruct neuronal development, according to Allen.

“It makes sense that you have this constant feedback going on between the neuron and the astrocyte,” says Allen. “They are sending signals to each other: ‘Am I in the right place?’ ‘Yes, you are.’ ‘I’ve made a connection now—do I keep it?’ ‘Yes, you do.’ And they keep going back and forth.”

Next, Allen and her team are studying whether these signals can be manipulated—for example, to stimulate neurons to repair synapses or form new ones in disorders of aging, such as Alzheimer’s disease.

(Image caption: Astrocytes (green) and neurons (magenta) closely interact in the developing cortex and signal to each other to ensure correct development. Credit: Salk Institute)

Neuroscientists roll out first comprehensive atlas of brain cells

When you clicked to read this story, a band of cells across the top of your brain sent signals down your spine and out to your hand to tell the muscles in your index finger to press down with just the right amount of pressure to activate your mouse or track pad.

A slew of new studies now shows that the area of the brain responsible for initiating this action — the primary motor cortex, which controls movement — has as many as 116 different types of cells that work together to make this happen.

The 17 studies, appearing online in the journal Nature, are the result of five years of work by a huge consortium of researchers supported by the National Institutes of Health’s Brain Research Through Advancing Innovative Neurotechnologies (BRAIN) Initiative to identify the myriad of different cell types in one portion of the brain. It is the first step in a long-term project to generate an atlas of the entire brain to help understand how the neural networks in our head control our body and mind and how they are disrupted in cases of mental and physical problems.

“If you think of the brain as an extremely complex machine, how could we understand it without first breaking it down and knowing the parts?” asked cellular neuroscientist Helen Bateup, a University of California, Berkeley, associate professor of molecular and cell biology and co-author of the flagship paper that synthesizes the results of the other papers. “The first page of any manual of how the brain works should read: Here are all the cellular components, this is how many of them there are, here is where they are located and who they connect to.”

Individual researchers have previously identified dozens of cell types based on their shape, size, electrical properties and which genes are expressed in them. The new studies identify about five times more cell types, though many are subtypes of well-known cell types. For example, cells that release specific neurotransmitters, like gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) or glutamate, each have more than a dozen subtypes distinguishable from one another by their gene expression and electrical firing patterns.

While the current papers address only the motor cortex, the BRAIN Initiative Cell Census Network (BICCN) — created in 2017 — endeavors to map all the different cell types throughout the brain, which consists of more than 160 billion individual cells, both neurons and support cells called glia. The BRAIN Initiative was launched in 2013 by then-President Barack Obama.

“Once we have all those parts defined, we can then go up a level and start to understand how those parts work together, how they form a functional circuit, how that ultimately gives rise to perceptions and behavior and much more complex things,” Bateup said.

Knock-in mice

Together with former UC Berkeley professor John Ngai, Bateup and UC Berkeley colleague Dick Hockemeyer have already used CRISPR-Cas9 to create mice in which a specific cell type is labeled with a fluorescent marker, allowing them to track the connections these cells make throughout the brain. For the flagship journal paper, the Berkeley team created two strains of “knock-in” reporter mice that provided novel tools for illuminating the connections of the newly identified cell types, she said.

“One of our many limitations in developing effective therapies for human brain disorders is that we just don’t know enough about which cells and connections are being affected by a particular disease and therefore can’t pinpoint with precision what and where we need to target,” said Ngai, who led UC Berkeley’s Brain Initiative efforts before being tapped last year to direct the entire national initiative. “Detailed information about the types of cells that make up the brain and their properties will ultimately enable the development of new therapies for neurologic and neuropsychiatric diseases.”

Ngai is one of 13 corresponding authors of the flagship paper, which has more than 250 co-authors in all.

Bateup, Hockemeyer and Ngai collaborated on an earlier study to profile all the active genes in single dopamine-producing cells in the mouse’s midbrain, which has structures similar to human brains. This same profiling technique, which involves identifying all the specific messenger RNA molecules and their levels in each cell, was employed by other BICCN researchers to profile cells in the motor cortex. This type of analysis, using a technique called single-cell RNA sequencing, or scRNA-seq, is referred to as transcriptomics.

The scRNA-seq technique was one of nearly a dozen separate experimental methods used by the BICCN team to characterize the different cell types in three different mammals: mice, marmosets and humans. Four of these involved different ways of identifying gene expression levels and determining the genome’s chromatin architecture and DNA methylation status, which is called the epigenome. Other techniques included classical electrophysiological patch clamp recordings to distinguish cells by how they fire action potentials, categorizing cells by shape, determining their connectivity, and looking at where the cells are spatially located within the brain. Several of these used machine learning or artificial intelligence to distinguish cell types.

“This was the most comprehensive description of these cell types, and with high resolution and different methodologies,” Hockemeyer said. “The conclusion of the paper is that there’s remarkable overlap and consistency in determining cell types with these different methods.”

A team of statisticians combined data from all these experimental methods to determine how best to classify or cluster cells into different types and, presumably, different functions based on the observed differences in expression and epigenetic profiles among these cells. While there are many statistical algorithms for analyzing such data and identifying clusters, the challenge was to determine which clusters were truly different from one another — truly different cell types — said Sandrine Dudoit, a UC Berkeley professor and chair of the Department of Statistics. She and biostatistician Elizabeth Purdom, UC Berkeley associate professor of statistics, were key members of the statistical team and co-authors of the flagship paper.

“The idea is not to create yet another new clustering method, but to find ways of leveraging the strengths of different methods and combining methods and to assess the stability of the results, the reproducibility of the clusters you get,” Dudoit said. “That’s really a key message about all these studies that look for novel cell types or novel categories of cells: No matter what algorithm you try, you’ll get clusters, so it is key to really have confidence in your results.”

Bateup noted that the number of individual cell types identified in the new study depended on the technique used and ranged from dozens to 116. One finding, for example, was that humans have about twice as many different types of inhibitory neurons as excitatory neurons in this region of the brain, while mice have five times as many.

“Before, we had something like 10 or 20 different cell types that had been defined, but we had no idea if the cells we were defining by their patterns of gene expression were the same ones as those defined based on their electrophysiological properties, or the same as the neuron types defined by their morphology,” Bateup said.

“The big advance by the BICCN is that we combined many different ways of defining a cell type and integrated them to come up with a consensus taxonomy that’s not just based on gene expression or on physiology or morphology, but takes all of those properties into account,” Hockemeyer said. “So, now we can say this particular cell type expresses these genes, has this morphology, has these physiological properties, and is located in this particular region of the cortex. So, you have a much deeper, granular understanding of what that cell type is and its basic properties.”

Dudoit cautioned that future studies could show that the number of cell types identified in the motor cortex is an overestimate, but the current studies are a good start in assembling a cell atlas of the whole brain.

“Even among biologists, there are vastly different opinions as to how much resolution you should have for these systems, whether there is this very, very fine clustering structure or whether you really have higher level cell types that are more stable,” she said. “Nevertheless, these results show the power of collaboration and pulling together efforts across different groups. We’re starting with a biological question, but a biologist alone could not have solved that problem. To address a big challenging problem like that, you want a team of experts in a bunch of different disciplines that are able to communicate well and work well with each other.”

(Image caption: Brain slice from a transgenic mouse, in which genetically defined neurons in the cerebral cortex are labeled with a red fluorescent reporter gene. Credit: Tanya Daigle, courtesy of the Allen Institute)