#dutch art

MWW Artwork of the Day (4/8/16)

Vincent Van Gogh (Dutch, 1853-1890)

Japonaiserie: Flowering Plum Tree [after Hiroshige] (July-Sept. 1887)

Oil on canvas, 55 x 46 cm.

Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam

At the Paris World Fair of 1867 Japanese culture burst upon the European scene with the force of a megaton bomb. Kimonos and bamboo screens became all the rage; Parisian ladies turned the tea ceremony into a competitive sport; Japanese woodblock prints appeared in every corner shop and were greedily snatched up by a public infected with “la fièvre japonaise.”

A few decades later, when the fever had subsided and the novelty had wore thin, an influential French critic, looking back over the phenomenon, declared that Japan had invigorated modern art in the same way that classical antiquity had the Renaissance. And the artist upon whom it had the most profound effect was Vincent van Gogh. As early as 1885 in Antwerp he started a collection of Japanese ukiyo-e prints, which by 1887 numbered in the hundreds. His enthusiasm went well beyond collecting: in spring 1887 he organized an exhibition of Japanese prints at the Cafe Tambourin, and that summer copied three prints, two by Hiroshige, in his personal collection. (Copying other works was the artistically unschooled Van Gogh’s method of learning.) Suddenly, the muted color palette of his Paris period brightened, previously shunned black-white contrasts appeared, the daring diagonals and jolting shifts in perspective of the prints found their way into his repertoire. Only one thing remained for Van Gogh, who never did anything in half-measures: he must “find his own Japan.” So he went to Arles, and the rest is, as they say, history.

This painting is a copy of a print in Hiroshige’s last collection, “One Hundred Famous Views of Edo.”

The MWW already contains a substantial number of works by Van Gogh in five separate exhibits, which include ALL his extant paintings, as well a selection of his drawings from each period. Extracts from Van Gogh’s literate and very revealing letters to his brother Theo accompany the pictures, along with the usual background information gleaned from many sources.

* Van Gogh in Holland (Oct. 1881-Feb. 1886)

* Van Gogh in Paris (March 1886-Jan. 1888)

* Van Gogh at Arles (Feb. 1888-April 1889)

* Van Gogh at St.-Rémy (May 1889-May 1890)

* Journey’s End: Van Gogh at Auvers (20 May-29 July 1890)

Post link

MWW Artwork of the Day (4/3/16)

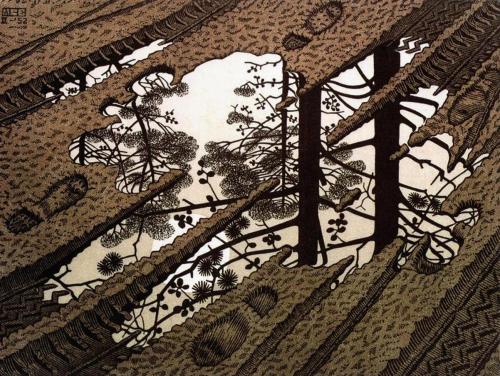

M.C. Escher (Dutch, 1898-1972)

Puddle (February 1952)

Woodcut in black, olive and brown, printed from three blocks, 23.9 x 32 cm.

Since 1936, Escher’s work had become primarily focused on paradoxes, tessellation and other abstract visual concepts. This print, however, is a realistic depiction of a simple image that portrays two perspectives at once. It depicts an unpaved road with a large pool of water in the middle of it at twilight. Turning the print upside-down and focusing strictly on the reflection in the water, it becomes a depiction of a forest with a full moon overhead. The road is soft and muddy and in it there are two distinctly different sets of tire tracks, two sets of footprints going in opposite directions and two bicycle tracks. Escher has thus captured three elements: the water, sky and earth.

Check out these two MWW Escher galleries which between them contain almost all of his work:

* M.C. Escher – The Early Years (1917-37)

* The Topsy-Turvy World of M.C. Escher (1938-1972)

Post link

MWW Artwork of the Day (3/28/16)

Gabriël Matsu (Dutch, 1629-1667)

The Old Drinker (c. 1657-58)

Oil on panel, 22 x 19.5 cm.

Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

On this minuscule panel, measuring just 22 x 19.5 cm, Gabriël Metsu painted with minute detail this everyday scene of an old man with his Gouda pipe and his pewter jar leaning on against a beer barrel. The old drinker looks rather the worse for wear; he sags rather than sits on the chair as he peers through his watery eyes, his chin unshaven, his collar open and his cap askew. Metsu presents the man with a direct honesty and realism that is not in fact harsh; the smile and the friendly eyes of the old drinker lend a certain sympathetic quality.

Metsu’s most widely acclaimed paintings are the genre pictures, generally depicting a small number of relatively large figures within an upright composition. In addition to his indoor genre scenes Metsu painted a handful of depictions of outdoor markets, a number of religious subjects and portraits, and a few still lifes. His only known pupil was the genre and portrait painter Michiel van Musscher (1645-1705).

(translated from the Museum website)

Metsu is one of the featured artists in the MWW exhibit/gallery:

* Dutch Masters II: Age of the Great Genre Painters (1650-75)

Post link

Details: Shipwreck off a rocky coast on March, Ludolf Bakhuizen, 1694

Details:Ships in Distress off a Rocky Coast, Ludolf Bakhuizen, 1667

Detail:A Vanitas Still Life with a Skull, a Book and Roses, Jan Davidsz. de Heem, 1630

There is a difference between Catholic and Protestant attitudes to painting,“ he explained as he worked, "but it is not necessarily as great as you may think. Paintings may serve a spiritual purpose for Catholics, but remember too that Protestants see God everywhere, in everything. By painting everyday things-tables and chairs, bowls and pitchers, soldiers and maids-are they not celebrating God’s creation as well?

- Tracy Chevalier, Girl with a Pearl Earring

Johannes Vermeer was the greatest of the Dutch genre painters, who took his subject matter from everyday life. However, Vermeer did not simply record the world around him, but he carefully crafted poetic constructions based on what he observed.

Estimated to have been painted around 1665, Girl with a Pearl Earring is the Dutch artist’s most famous painting.

The painting has become as intriguing in its modest way as the Mona Lisa. Ineed it is often refered to as ‘The Mona Lisa of the North’. The girl’s face turned toward us from centuries ago demands that we ask, who was she? What was the thinking? What was the artist thinking about her?

It is not a portrait but a tronie - the head of an ideal type, it depicts a young beautiful woman in an exotic dress, wearing an oriental turban and an improbably large pearl in her ear. Even though a girl possibly sat and posed for this painting, it displays too few distinctive features - there are no moles, scars or freckles to be seen.

Set against a black background, the young woman features the striking blue and yellow turban and a glistening pearl. Vermeer’s mastery of light and shade can be seen on her luminous skin, while subtle glimmers of white on her parted red lips make them appear moist. Although we don’t know the identity of the girl, she looks familiar, mostly due to the intimacy of her gaze. However, by leaving the corners of her eyes undefined, the artist offers no clue of her emotional state. Her expression is pleasingly ambiguous, contributing to the work being an iconic masterpiece.

I think there are three qualities that make Girl with a Pearl Earring so seductive. It is very beautiful, for one thing. The striking blue and yellow of the girl’s headscarf, set against a black background, the glistening pearl created in a few swift strokes, the expert capturing of light and shade on her luminous skin, the liquid pools of her eyes: all add up to a work of sublime beauty.

But beauty is not enough to sustain the sort of attention Girl with a Pearl Earring receives. I’ve been looking at this painting for over 30 years, and I’m still not bored of it. Why?

Its second seductive characteristic is that the girl looks familiar. We may not know who she is, but we feel we know her because she is looking at us with such intimacy. We mistake this look for familiarity. I’ve had readers tell me that their daughter or their friend or their neighbor resembles the girl. I’ve seen many women online dressed up as her. Someone once told me that I look like the girl, and that must be why I wrote about the painting.

However, we don’t really know what she looks like – not even the basics like hair or eye color. With her face turned partially away, we can’t really discern its shape. The line of her nose blends into her check so we don’t know if it’s wide, snub, or round. Her look is universal rather than specific. In fact, the painting is not actually a portrait of a particular person, but what the Dutch called a tronie – the head of an ideal “type,” like “a soldier” or “a musician” – or, in this case, “a young beauty.”

This leads to the third and most powerful quality of the painting: its mystery. We don’t know who the girl is or what she’s thinking. Indeed, we know very little about Vermeer. He lived his whole life in the Dutch town of Delft. He married a Catholic woman and probably converted, he lived at his mother-in-law’s, and had 11 children. He was in debt several times. He was an art dealer as well as an artist – and that’s about the extent of our knowledge, apart from his work.

The girl’s expression is pleasingly ambiguous. Is she happy or sad? Is she pushing us away or yearning to look at us? And who is “us,” anyway? I had been studying the painting for years when one day it dawned on me: of course she’s not looking at me like that – I wasn’t there! She’s looking at the painter with that curious wide-eyed gaze. It made me wonder what Vermeer did to her to make her look like that at him. That curiosity was what led me to write a novel about the painting: I wanted to explore the mystery of her gaze. To me Girl with a Pearl Earring is neither a universal tronie, nor a portrait of a specific person. It is a portrait of a relationship.

In considering the painting, there is an immediate beauty that draws us in, and a familiarity that satisfies us. But in the end, it is the mystery that keeps us coming back to it again and again, looking for answers that we never find.

Beauty, familiarity, mystery. These are the qualities of Girl with a Pearl Earring that make it an iconic masterpiece. The painting is like a song that ends on the second-to-last chord: we are drawn to look at it again in the hope that this time the last chord will be played, the painting will resolve itself, the mystery will dissipate, and we can leave the girl alone at last.

Vermeer created 36 paintings that we’re aware of, many of them depicting women on their own, doing everyday things like pouring milk, writing letters, playing lutes. We have no idea who these women are, though they are likely to be members of the family household. This means we don’t know what the relationship is between the girl wearing the pearl earring and the painter.

Tracy Chevalier’s story shares some of the striking qualities of Vermeer’s paintings. Her subject is a single woman caught in a private moment. Like the Dutch master, she’s fascinated by the play of light, the suggestive power of small details, and the subtle thoughts beneath placid expressions.

The story is told by Griet, a young woman in Delft. Her family, never prosperous, has been thrown into desperate circumstances by a recent kiln accident that blinded her father. While her young brother is sent to a harsh tile factory, Griet finds work as a maid in the home of Johannes Vermeer.

Now and then Chevalier’s style seems self-consciously rich. Her poor, illiterate narrator sounds at times as though she’s earned a master’s degree in creative writing, as the author has. But, that aside, Chevalier re-creates common life in Delft with fascinating authenticity. The smells of the marketplace, the drudgery of laundry, the subtle tensions between servants – it all comes across here viscerally.

Vermeer’s house is full of his own children and other people’s paintings. Griet finds it something of a land mine. Their Roman Catholic faith is an unsettling mystery to her. The painter’s daughters are eager to test her authority. His wife resents the competition for her husband’s attention. And the careful old mother-in-law is willing to do anything to increase Vermeer’s meager artistic output.

With wonderfully effective restraint, Chevalier captures the glances and brief comments that gradually lead Griet into her master’s studio, his painting, and finally his heart.

Any sign of intimacy with Vermeer’s work would mean certain dismissal by the painter’s captious, continually pregnant wife, but Griet can’t help but stare at his haunting portraits when everyone else has gone to bed.

Though they’re very quiet moments, the most exciting scenes are those of Griet slowly learning to see with greater perception and understand the nature of light and shadow. Soon, she’s making crucial recommendations to the master about shading, composition, and color.

When Vermeer’s raunchy patron insists on a portrait of Griet, he forces a crisis that exposes the thicket of affections and jealousies coursing below the surface of this house.

"I wanted to know the man who painted like that,” Griet thinks one day while dusting Vermeer’s studio. That knowledge is ultimately denied her - and us - but his elusive quality seems as accurate as the rest of this luminous novel.

Tracy Chevalier’s novel speculating about the painting was of course filmed by Peter Webber, who casts Scarlett Johansson as the girl and Colin Firth as Vermeer. I can think of many ways the film could have gone wrong, but it goes right, because it doesn’t cook up melodrama and romantic intrigue but tells a story that’s content with its simplicity. The painting is contemplative, reflective, subdued, and the film must be, too: We don’t want lurid revelations breaking into its mood.

Sometimes two people will regard each other over a gulf too wide to ever be bridged, and know immediately what could have happened, and that it never will. That is essentially the message of this quiet lush film.

Post link

Hendrick Goltzius (1558–1617, The Netherlands)

The Creation of the World

Goltzius was a Dutch printmaker, draftsman, and painter. He was the leading Dutch engraver of the early Baroque period, a leading example of the Northern Mannerism style, noted for his sophisticated technique and the exuberance of his compositions. According to A. Hyatt Mayor, Goltzius “was the last professional engraver who drew with the authority of a good painter and the last who invented many pictures for others to copy”. In middle age he also began to produce paintings.

Post link

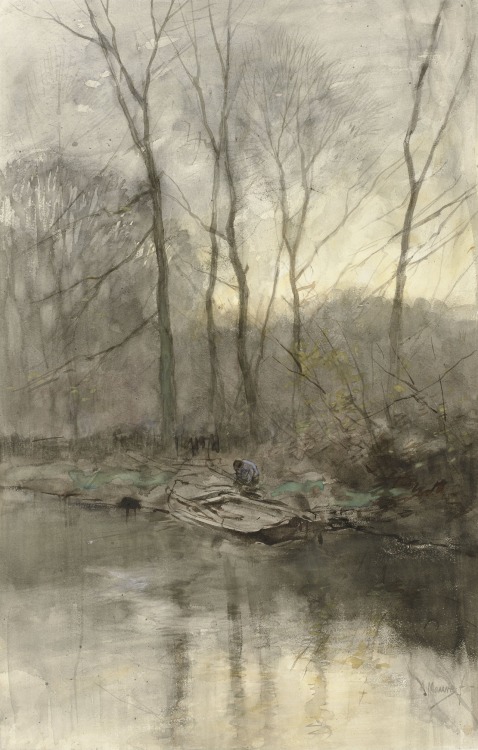

Anton Mauve (1838–88, The Netherlands)

Watercolours

Mauve was a Dutchrealist painter who was a leading member of the Hague School. A master colourist, he was a significant early influence on his cousin-in-law Vincent van Gogh. His best known paintings depict peasants working in the fields. His paintings of flocks of sheep were especially popular with American patrons.

Post link

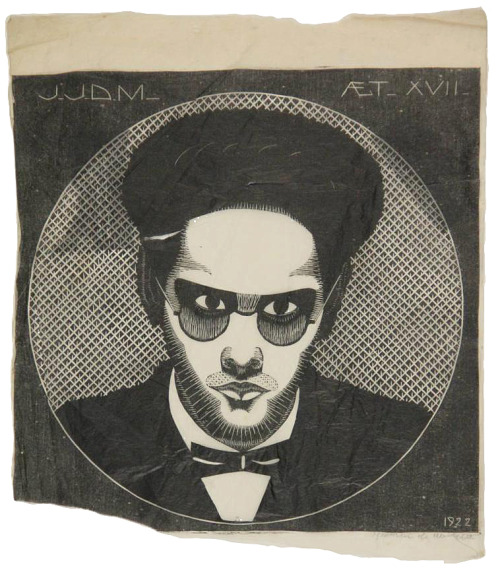

Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita (1868-1944) - Portrait of his son Jaap (1905-1944), woodcut, 1922.

Post link

The World as Object- Roland Barthes

The simple act of perception transforms the objective landscape into a human landscape. The Dutch masters have used the canvas as a metaphor for the way that we do this. Their paintings have traditionally shown a world which is utilized by the human. It has also depicted cultural divide between the patrician (the rich, who have power) and the peasant (who are subject to the power of the…

Portrait of Lucia Wijbrants (Detail)

Gabriël Metsu, 1667

Peter Paul Rubens - The Fall of Phaeton

1604

oil on canvas

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Post link

Hendrick Avercamp - Skaters playing kolf

1625

oil on canvas

Houston Museum of Fine Arts, Texas

Post link

Marten Boelema de Stomme - Still-Life with Nautilus Cup

17th century

oil on panel

Hallwyl Museum, Stockholm

Post link

Rogier van der Weyden - Portrait of Antony of Burgundy

Circa 1460

oil on panel

Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels

Post link

Egbert van Heemskerck - An Alchemist in His Study

17thcentury

oil on canvas

Chemical Heritage Foundation, Philadelphia

Post link

Pieter Bruegel the Elder - The Magpie on the Gallows (1568)

“Bruegel’s painting was created the year after Fernando Álvarez de Toledo, 3rd Duke of Alba, arrived in the Netherlands, sent by the Spanish king, Philip II to suppress the Dutch Revolt. The gallows may represent the threat of execution of those preaching the new Protestant doctrine, and the painting may allude to several Netherlandish proverbs. There is a direct allusion to the Netherlandish proverbs of dancing or shitting on the gallows, meaning a mocking of the state. It also alludes to the belief that magpies are gossips, and that gossip leads to hangings. And that the way to the gallows leads through pleasant meadows. It is not known why or for whom the picture was painted. Its date of 1568 makes this painting one of Bruegel’s last works before his death in 1569; indeed, perhaps his final work. Bruegel asked his wife to burn some of his pictures on his death, but told her to keep the Magpie on the Gallows for herself.”

Source

Post link

Tethys. Goddess of the Waters, Hendrick Goltzius (Dutch, 1558-1617), ca. 1590

Chiaroscuro woodcut print on paper

Joseph Interpreting the Dreams of His Fellow Prisoners Artist: Master of the Story of Joseph (Netherlandish, ca. 1500) Medium: Oil on wood Dimensions: Diameter 61 ½ in. (156.2 cm) Classification: Paintings Credit Line: Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1953 Accession Number: 53.168 Metropolitan Museum of Art