#german film

Half the fun of watching German director Tom Tykwer’s thriller RUN LOLA RUN (’98) is reveling in all of the visual details. There is so much to take in from Frank Griebe’s excellent cinematography to the brilliant use of color and objects that enhance the film’s themes. RUN LOLA RUN stars Franka Potente as Lola, a young woman who must secure 100,000 Deutschmarks and deliver the money to her boyfriend Manni (Moritz Bleibtreu), who desperately needs the cash to pay off a violent gangster. Lola has 20 minutes to complete her mission. The film explores three different outcomes as Lola encounters a variety of obstacles along the way.

Let’s first look at the film’s brilliant use of color. Red and yellow are strategically associated with the two lead characters. Lola is presented with the color red. Her hair is dyed bright red, and each of the three-time loops begins with her hanging up a red phone. Red continually appears at various points in her story, whether it’s a bicycle thief wearing a red shirt or her carrying a red bag full of cash. The image of Potente wearing a red wig and running through the streets of Berlin has become the visual symbol of RUN LOLA RUN and usually the first thing that people will remember about the film. Yellow is Manni’s color. He calls Lola from a yellow telephone booth as he contemplates robbing the grocery store across the street, which just happens to be adorned with yellow fixtures and trim.

Red can be seen to symbolize passion but is also represents speed, especially since Lola is moving at such a frantic pace. Yellow is the complete opposite. It symbolizes the tension-filled act of waiting. This can be observed in one particular scene in which workers dressed in yellow hazmat suits carry a large piece of glass from one side of the street to another. They are confronted with a red ambulance driving at a high speed to bring a cardiac patient to the hospital. This scene is played out in each of the three scenarios with a different result. In other scenes, Lola passes a yellow subway tram, a visual reminder that time is passing and Manni is waiting for her.

One of my favorite, and a bit more subtle, use of color in the film is when green is associated with some form of authority. When Lola visits her dad’s bank to ask for money, his office is adorned with green furniture and a large green painting that Lola rips off the wall in anger. In one scenario, policemen driving green and white vehicles and dressed in green uniforms confront Lola and Manni.

Because the film is so focused on time—not only how Lola is pressed for time but also how one small act can change one’s destiny—clocks and watches are important symbols that pop up throughout the film. There is a big ornate clock in Lola’s bedroom, the face of which is taped over with green stickers, which could be seen as a symbol of how time exerts its authority over her. Manni is constantly checking the clock that hangs above the grocery store entrance, Lola shatters the glass clock in her father’s office with her ear-piercing scream and an old lady checks her watch to give Lola the time. In the casino scene, Lola chooses to play the number 20 on the roulette wheel, which plays to the fact that she only has 20 minutes on the clock to finish the job.

Tom Tykwer drew a lot of inspiration from Alfred Hitchcock’s classic thriller VERTIGO (’58). For the casino scene, Tykwer had production designer fill in empty space on the wall by creating a replica of the iconic Carlotta painting from Hitchcock’s film. VERTIGO also inspired the spiral motif that can be seen throughout the film. As Manni calls from the yellow phone booth, the viewer can spot a shop called Spirale in the background complete with a spiraling fixture. When Lola sets out on her mission, she runs down a spiral staircase, presented in the film through animation rather than live-action. As each of the time loops resets, we see Lola and Manni, contemplating life while resting on pillows with a spiral print.

Cinematographer Frank Griebe also employs the sensation of vertigo through many excellent camera shots. Arc shots, in which the camera circles a subject, are used throughout the film. There are lots of tight close-ups, tracking shots, low angle-shots and top-down perspectives, which beautifully demonstrate the heightened emotion and tension felt by the characters. The camera is constantly moving and so is the imagery. In addition to animation, there are black-and-white flashback scenes, stop motion sequences and when time stops for a moment, those scenes are presented with a hazy filter. The bounty of visual symbolism and the film’s frenetic pace make RUN LOLA RUN a highly enjoyable experimental thriller.

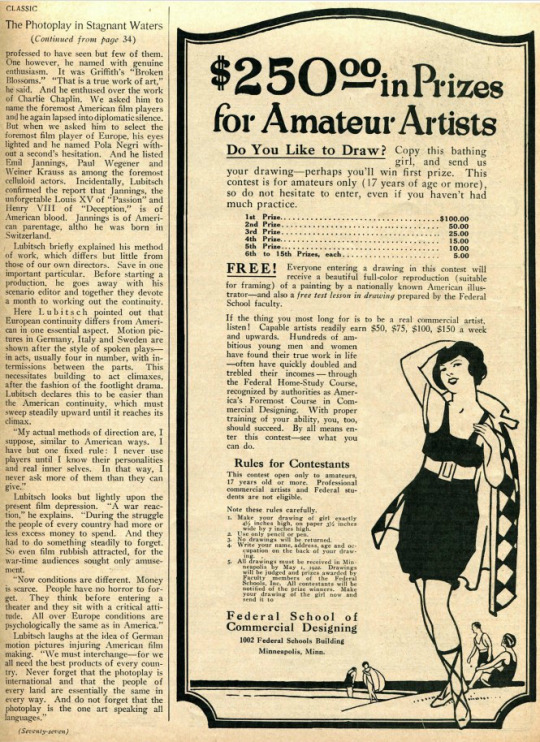

fromMotion Picture Classic, April 1922

Transcription:

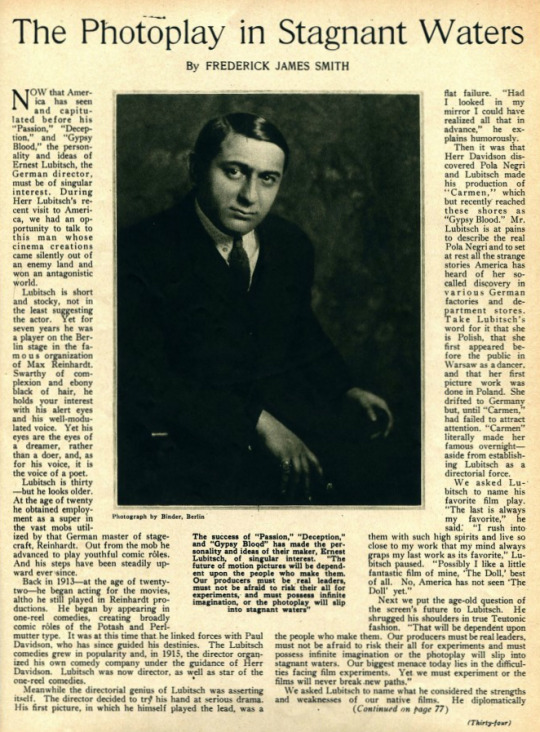

NOW that America has seen and capitulated before his “Passion,” “Deception,” and “Gypsy Blood,” the personality and ideas of Ernest [sic] Lubitsch, the German director, must be of singular interest. During Herr Lubitsch’s recent visit to America, we had an opportunity to talk to this man whose cinema creations came silently out of an enemy land and won an antagonistic world.

Lubitsch is short and stocky, not in the least suggesting the actor. Yet for seven years he was a player on the Berlin stage in the famous organization of Max Reinhardt. Swarthy of complexion and ebony black of hair, he holds your interest with his alert eyes and his well-modulated voice. Yet his eyes are the eyes of a dreamer, rather than a doer, and, as for his voice, it is the voice of a poet.

Lubitsch is thirty—but he looks older. At the age of twenty he obtained employment as a super in the vast mobs utilized by that German master of stagecraft, Reinhardt. Out from the mob he advanced to play youthful comic rôles. And his steps have been steadily upward ever since.

Back in 1913—at the age of twenty-two—he began acting for the movies, altho he still played in Reinhardt productions. He began by appearing in one-reel comedies, creating broadly comic rôles of the Potash and Perlmutter type. It was at this time that he linked forces with Paul Davidson, who has since guided his destinies. The Lubitsch comedies grew in popularity and, in 1915, the director organized his own comedy company under the guidance of Herr Davidson. Lubitsch was now director, as well as star of the one-reel comedies.

Meanwhile the directorial genius of Lubitsch was asserting itself. The director decided to try his hand at serious drama. His first picture, in which he himself played the lead, was a flat failure. “Had I looked in my mirror I could have realized all that in advance,” he explains humorously.

Then it was that Herr Davidson discovered Pola Negri and Lubitsch made his production of “Carmen,” which but recently reached these shores as “Gypsy Blood.” Mr. Lubitsch is at pains to describe the real Pola Negri and to set at rest all the strange stories America has heard of her so-called discovery in various German factories and department stores. Take Lubitsch’s word for it that she is Polish, that she first appeared before the public in Warsaw as a dancer, and that her first picture work was done in Poland. She drifted to Germany but until “Carmen,” had failed to attract attention. “Carmen” literally made her famous overnight—aside from establishing Lubitsch as a directorial force.

We asked Lubitsch to name his favorite film play. “The last is always my favorite,” he said: “I rush into them with such high spirits and live so close to my work that my mind always graps [sic] my last work as its favorite,” Lubitsch paused. “Possibly I like a little fantastic film of mine, ‘The Doll,’ best of all. No, America has not seen ‘The Doll’ yet.”

Next we put the age-old question of the screen’s future to Lubitsch. He shrugged his shoulders in true Teutonic fashion. “That will be dependent upon the people who make them. Our producers must be real leaders, must not be afraid to risk their all for experiments and must possess infinite imagination or the photoplay will slip into stagnant waters. Our biggest menace today lies in the difficulties facing film experiments. Yet we must experiment or the films will never break new paths.”

We asked Lubitsch to name what he considered the strengths and weaknesses of our native films. He diplomatically

(Continued on page 77)

Photo Caption:

The success of “Passion,” “Deception,” and “Gypsy Blood” has made the personality and ideas of their maker, Ernest [sic] Lubitsch, of singular interest. “The future of motion pictures will be dependent upon the people who make them. Our producers must be real leaders, must not be afraid to risk their all for experiments, and must possess infinite imagination, or the photoplay will slip into stagnant waters”

The Photoplay in Stagnant Waters

(Continued from page 34)

professed to have seen but few of them. One however, he named with genuine enthusiasm. It was Griffith’s “Broken Blossoms.” “That is a true work of art,” he said. And he enthused over the work of Charlie Chaplin. We asked him to name the foremost American film players and he again lapsed into diplomatic silence. But when we asked him to select that foremost film player of Europe, his eyes lighted and he named Pola Negri without a second’s hesitation. And he listed Emil Jannings, Paul Wegener and Weiner [sic] Krauss as among the foremost celluloid actors. Incidentally, Lubitsch confirmed the report that Jannings, the unforgettable Louis XV of “Passion” and Henry VIII of “Deception,” is of American blood. Jannings is of American parentage, altho he was born in Switzerland.

Lubitsch briefly explained his method of work, which differs but little from those of our own directors. Save in one important particular. Before starting a production, he goes away with his scenario editor and together they devote a month to working out the continuity.

Here Lubitsch pointed out that European continuity differs from American in one essential aspect. Motion pictures in Germany, Italy and Sweden are shown after the style of spoken plays—in acts, usually four in number, with intermissions between the parts. This necessitates building to act climaxes, after the fashion of the footlight drama. Lubitsch declares this to be easier than the American continuity, which must steadily build upward until it reaches its climax.

“My actual methods of direction are, I suppose, similar to American ways. I have but one fixed rule: I never use players until I know their personalities and real inner selves. In that way, I never ask more of them than they can give.”

Lubitsch looks but lightly upon the present film depression. “A war reaction,” he explains. “During the struggle the people of every country had more or less excess money to spend. And they had to do something steadily to forget. So even film rubbish attracted, for the war-time audiences sought only amusement.

“Now conditions are different. Money is scarce. People have no horror to forget. They think before entering a theater and they sit with a critical attitude. All over Europe conditions are psychologically the same as in America.”

Lubitsch laughs at the idea of German motion pictures injuring American film making. “We must interchange—for we all need the best products of every country. Never forget that the photoplay is international and that the people of every land are essentially the same in every way. And do not forget that the photoplay is the one art speaking all languages.”

Bringing out all these things on the screen, separating them from the incidentals, seems to me to confront a film, a film based on factual reports, with a more substantial responsibility than the artistic reproduction of events: the responsibility of sounding a warning from real events, of educating, and in this way ultimately having a preventive effect…

Peter LorreinM(Fritz Lang, 1931), the story of the hunt for a pedophile killer through the underworld of Berlin

Post link

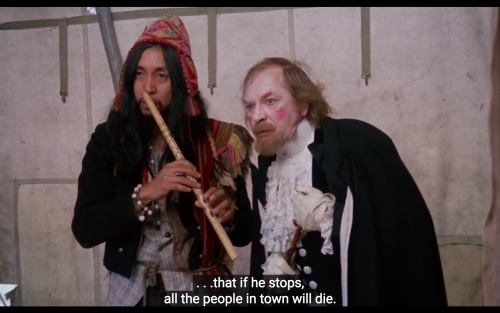

Kidlat Tahimik as “Hombrecito” in The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (1974), directed by Werner Herzog.

Post link

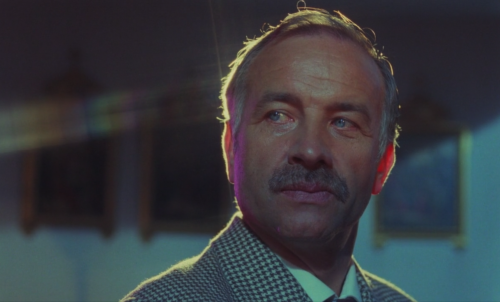

Winner of 6 German Oscars (including Best Film and Best Director), The People vs. Fritz Bauer opens New York and Los Angeles on August 19th followed by select cities. Find our latest list of openings below.