#historical fencing

I’ve often been asked, “How do you suggest that someone start training with swords?”. Here’s a full video to give you the best advice I can. Best of luck, and welcome to the journey!

Transcript below.

My apologies for the low audio levels- you need to boost the volume or put on headphones.

TRANSCRIPT (with images and hotlinks):

I’ve often been asked, how do you suggest that someone start training with swords?

It depends on what you’re interested in! Sword-fighting comes in many forms.

There were rich martial traditions both in the east and west, but I’ll focus on European styles. Perhaps you want to revive the martial systems preserved in ancient fighting books, or to connect with heroism in history and mythology. You might want to master the meditative art of cutting, or to fight for glory in prestigious competitions, or create dynamic fight scenes for stage and screen, or reenact epic battles with a field full of fellow warriors, or compete at full force for the glory of team and country There are so many ways and reasons to sword fight! Also, within the type of sword fighting you want to do, there are dozens of weapons and forms to study.

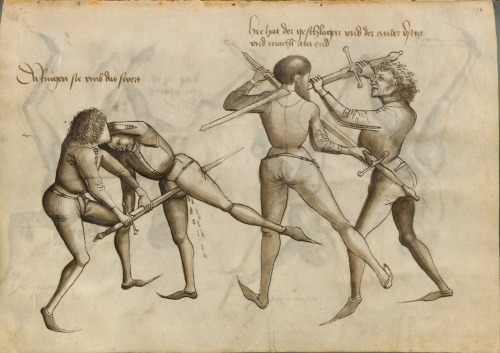

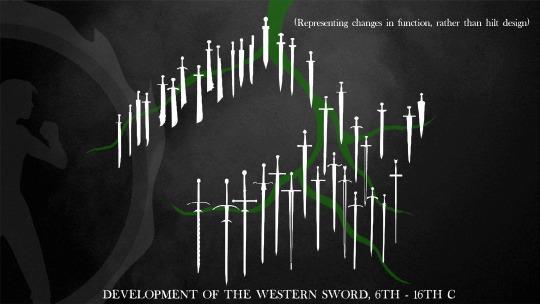

We have limited documentation of European martial arts, so the bulk of the historical swordsmanship revival focuses on the 14th to 19th centuries. It is especially strong around the German and Italian schools of medieval swordsmanship, since that’s where most of the martial arts records have survived. There are also strong traditions from the Spanish, French, English and Scottish schools that grew during the Renaissance. These later evolved into classical fencing, and then modern fencing as we know it today. With these meanings of swordsmanship in mind, the first thing is to do some internet research and find out what is near you. Also, you’ll need to find a person or at the very least a tool to practice with!

You need tools to be able to train. Your sword or sword-like object should have a blunted end and any sharp burrs or splinters should be sanded off with sandpaper or rasp. These are some wooden wasters that I’ve used in the past. I now work with a unique wooden sword, designed specially for my needs. If your sword is far too heavy, it will teach you bad habits, and is potentially dangerous for anyone that you’re training with. Historically, most swords weighed between 1-3 pounds or, a kilogram. They were sophisticated, agile, and streamlined for fighting. To study historical fencing, you’ll want an agile tool that is going to give you the best response. However if you want to fight in armored battles, the weapons you’ll use will be limited by the rules of the combat sport that you do. In combat sports, a weapon’s function always changes so that it’s safer and less lethal. Blades will be thick and rounded, suitable for cuts instead of thrusts.

For Historical European and Western Martial arts, most clubs train with wooden or nylon wasters before graduating to steel longswords, sabers and arming swords. However, rapier and side-sword students tend to go straight into using steel. You can find a range of gear at any of these shops online, through Ebay and on Amazon. It’s best to read reviews before purchasing anything.

For higher-intensity combat styles such as Heavy Medieval Battle, the International Medieval Combat Federation, and the Armored Combat League, you want to get gear that can take some punishment. Most of this equipment comes from individual blacksmiths working with clubs, so it’s best to ask around for good suppliers. However if you’re based in the US, you can get good gear at IceFalcon Armoury, or through the Facebook group, Cat’s Discount Armor Emporium.

Common sense checkpoint!

Fantasy weapons and collectibles are not made for training. Whilst having some kind of sword is better than no sword at all, just remember the steel and balance on a collectible isn’t going to be the same as a real weapon, so if you use it to hit something the metal will chip, bend or shatter. There are many suppliers out there making great equipment. There’s really no excuse to practice with a wall-hanger if you’re serious about swordsmanship.

If you want to learn historical European swordsmanship, there is a wealth of education available. The best resource we have is theWiktenauer, a wiki with a huge collection of source material. Books, DVDs and online channels like Youtube will also give you a strong base for learning at home, if you’re too far to travel to a reputable school. You can use the HEMA Alliance Club Finder to connect with groups near you. A lot of groups aren’t even listed there, but it’s still a great place to start. You can also start your own study group for your region. When you’re researching historical manuscripts, there is a lot to learn. There are many forums and social media groups who can help you make sense of them. Forums also help you meet instructors to answer specific questions and help you grow. Also, go to events! They often have workshops, and it’s great to just turn up and meet the community, even if you’re not training yet.

If you are looking to get started without making a financial investment, all you need is a sword or sword like object and a pell (or pole) to strike. Striking the pell is a medieval training exercise that will teach you targeting and coordination needed to work with weapons.

Sword fighting is dangerous when people are dangerous. Building precision and trust with your partner is the way to develop as a martial artist. Realistically, most people starting to sword-fight just want to play and have fun. So how can you have fun and still stay safe?

1) You could find an instructor who can teach you the risks and keep you in line 2) You can use equipment that is built for play-fighting, such as foam LARP swords, rubber swords or other soft simulators. There are some lovely simulators on the market now that are very nice to work with and really well balanced. 3) You can practice and master your coordination with a sword, use a lot of control, and work with someone you trust. Hey, that’s fun, right?

To stay truly safe you need to be on the same page as your partner, no matter how much safety equipment you wear. If one of you is Jack Sparrow and the other is out to win Longpoint, then there’s going to be a problem. Remember, sword fighting is dangerous when people are dangerous. If you’re training (or even just playing around) with a partner I strongly recommend wearing safety glasses, or even sports sunglasses that wrap over your eyes. There are lots of different goggles built for extreme sports. You don’t have to go buy expensive goggles, but safety glasses are a cheap way to look after yourself. I keep several pairs with my gear at all times. As soon as you can afford a medieval helmet or fencing mask, I urge you to buy one as they’ll really help protect you during your training. You will want some protection for the back of the head, such as this leather mask overlay from SPES Historical Fencing Gear. I have more advice about simple safety gear when you’re on a budget on my ‘Sword Combat FAQs’ page. You can also check out the Facebook group, ‘HEMA Hacks’ for useful gear-crafting ideas! As you become more involved with sword training, you’ll want to get better equipment, especially when it’s time to join a group.

Sword groups come in all shapes and sizes, and we use a lot of different names to describe what we do. There’s no 'one right way for everyone’ when you start learning to use weapons, and each style will have a different approach or rule set based on the comfort level of the participants. Instead of stressing about starting with the very best group, it’s more important that you keep looking for better instructors and competitors as you go, even if it means changing groups eventually. Be aware that within the martial arts community different forms are judged very harshly, based on whether people think that they’re valid- and I’m not only talking about medieval sword sports.

There simply isn’t a one-size fits all solution when you’re learning to become a martial artist, and what feels good and engaging to one person may feel threatening and uncomfortable to another.

It can be confusing, but just getting started and trying different things really is the best way to learn your way around. Once you know the type of sword fighting you want to do, and what groups offer it, you can start trying them out to find a good fit for you. Qualities you should look for in a group are: Open, positive attitudes to training and other groups, Committed members who come for weekly sessions or at least fortnightly, and regular sparring. Now, if the group are purely for scholarship, there should still be some form of practical testing of what you find. Another thing to look for in a good group is if they encourage members to cross-train for their own growth.

If a group restricts or actively discourages members from meeting with others, then there is something very weird going on. Every new physical experience helps a fighter grow, so it’s good to encourage cross-training at every opportunity, especially if it’s out of your comfort zone. Just remember cross-training should be a supplement to the main thing that you want to learn. If a group are afraid to spar or fight, ”in case someone gets hurt" then it’s probably a sign that the instructors aren’t confident in the techniques they are teaching or their ability to control their environment Physical safety is very important, but it also needs to be balanced with actual practice. That’s the only way to improve! Swordsmanship is a wonderful art, one that you will never stop learning. Welcome to the journey.

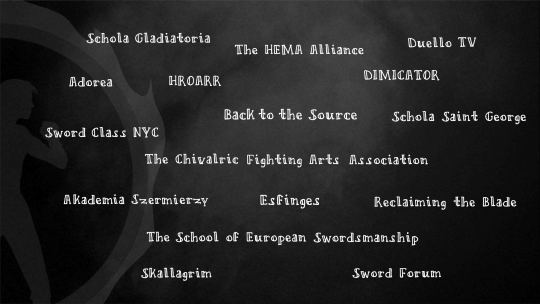

Want more great sword content? Here are some places to start.

You can also follow me on my social media channels where I share news and interesting things from around the wide world of swordsmanship. The swords depicted in the background of this video are from the makers Albion. You can check out their range of museum replica swords at Albion swords dot com. These, and other images were Royalty-free through Content Samurai, or I’ve credited their sources wherever possible. Thanks for watching!

Really pretty wooden dussacks by MacDonald Arms.

http://www.macdonaldarms.com/armoury/DusacksOfDistinction.php

Post link

Definitely falls under the “Look at me, I am a badass” category of devices.

A long time ago, when I first got my Castille Armory 3-Weapon mask,I spoke about how I would much rather have extra padding in the liner, where, by default, there was empty space.

Well, I finally did it. All it took was some performance/silky(?) feeling fabric with felt padding. It feels pretty nice and snug. Really, the only down side is that my glasses fog much more easily.

Post link

Some Meyer Dussack by the Davis Historical Fencing Club.

I have updated my list of feders and amended some info on the Black Horse Blades feder.

I have also included a very late update to my gloves list to include the sparring gloves fingered gloves.

Cold Steel’s Plastic Parrying Dagger.

I got this as a cheap loaner. I haven’t used this, yet, but Cold Steel’s plastic seems to be able to stand up to a lot.

It has some flex, but is still pretty stiff; Stiffer, than kind, in the thrust.

The guard is pretty chunky, as expected. I am not a big fan of how the quillons branch out laterally to the flat of the blade. I would have at least liked an s-shaped guard.

The part I like least about it is the handle. In addition to it being thick, the texture doesn’t make sense to me.

Post link

L'evoluzione della scherma nei secoli

© autore Massimiliano Longo.

Source:www.fioredeliberi.it

Post link

Updated COLOR version of “You are a sword.”

Buy it as a tee here:

http://www.redbubble.com/people/astormofquills/works/9882972-boy-girl

Post link

A momentary resurrection of this dead channel:

If you haven’t already seenwww.ringeck.netand have any interest in medieval longswordormartial arts coaching, then do yourself a favour and go check out Tea’s work.

That recent guest instructorship meant I have sparring footage of myself since Stefano demanded I bout him, and he arranged for it to be videoed.

If I want to get better, then I should watch it all and analyze it closely. Especially as I have seldom bothered to video my sparring in a long time.

I can already see my weak knee collapsing inwards on the lunge. That’s atrocious, and no wonder it hurt the next day. There’s also cutting at the sword and many more terrible sins of fencing.

If I’m going to have to swallow some pride and pore over this footage, I may compile an analysis edit. It’s something I’ve done before. Would that interest anyone?

Combat sports, whether full contact or not, are skill sports. That is to say that skill generally has a greater impact on results than athleticism.

That’s debatable. Even before we discuss them as alternatives, athleticism isn’t a single discrete attribute, and neither is skill. Hell, strength is a skill, as StrongFirst folks love to say.

Athleticism might include absolute strength, explosivity, muscular endurance… and those are just different kinds of strength. Then we can talk about cardio-vascular endurance, and things like having a Jon Jones or Michael Phelps type “perfect freakish build for your sport”. Some kinds of athleticism are relatively fixed attributes, like reach, while others are much more open to improvement by training.

Skill, too, can come in many kinds, from tactical acumen to technical perfection to mindset. Most of these are trainable, even if an individual will retain strong habits or preferences.

Nevertheless, I’d say that combat sports, especially non-full contact ones like HEMA, are skill sports as skill levels have more of an impact than athletic levels. This isn’t to say that skill always beats athleticism, but skill difference is more important to the result than athleticism differences between competitors.

Athletic supremacy can certainly make up for skill deficiency. What is less discussed is that athleticism’s impact on performance isn’t just a matter of binaries (as the Heavy Hands folks say, you’re either faster than them, or slower, quantifying it doesn’t add much) but of adequacy.

Matches go on for fixed times or numbers of exchanges. It isn’t necessary to be able to outlast the opponent as long as you can fence that many exchanges. If you’re going to gas on exchange 15 and he’s going to gas on exchange 11, but the match is best of 10 exchanges - does it matter? Well, it may be that you can push your pace higher if you aim to also gas on exchange 11 and so win more of those 10 exchanges, but the point is that with sufficient endurance you won’t simply lose by exhaustion like you would if you only had 7 rounds in the tank.

Similarly, it doesn’t significantly affect your fencing if you can do the full splits or not, but it will affect it if you don’t have the flexibility to make a normal lunge and recovery.

It’s nice to be more athletic than your opponent, but it’s necessary to meet this minimal level of athleticism. And the sad truth is that (at least in the HEMA scene here) a great many people don’t.

What to do about it? Coming soon in Part 2.

Emergency Negativity Vent

In seeing a lot of discussions on FB about HEMA that are reminding me exactly why I can’t find any joy in it these days. Or at least find little in most of the community.

I mean there’s the odd voice of reason, but so many that just make me facepalm.

I’ve written before about the need to accept as well as manage risks and this week my dice roll came up snake eyes.

My own stick bounced back while doing some pattern drills and cracked a tooth in half. My mouthguard was in its box ten feet away.

In hindsight I was probably pushing my competence at the drill with the energy and movement we were adding, but this is about the worst consequence I can foresee happening from that drill goig awry, and Im cool with it. I’ve already had the tooth glued back together.

Dear Diary

I’ve not been training HEMA much if at all of late. I went to Ireland and spent a week mucking out stables and relaxing with the Gassmanns - and getting my butt kicked in sparring by them and their clubmates.

Still impressed that Sam G was the only UK+Ire guy to leave longsword pools and Minsk and Jack G got Bronze (for Switzerland), but they were definitely in good form while I was rusty and unenthused about HEMA. Still, the opportunity to try basic horsemanship was amazing.

After that it was almost straight to the Vieira Bros BJJ camp in Spain for ten sessions of BJJ with world champions. It was, oddly enough, not so much intense as cumulatively overwhelming. There wasn’t that much new material (for me, but I’ve regularly attended Rico Vieira seminars over the years) but the overwhelming impression was that I just need to apply what I know to improve, not learn more.

Between that and a new copy of BJJ Training Diary (more to follow on that) I’ve been trying to be as intentional and focused in training as possible, and focusing on improving my game as applied rather than what I think my game is.

What does that mean?

I like the four stage competence ladder model of learning, ever since Scott Brown first introduced me to it.

My BJJ journey is at a point where I know a lot of things that I should do, and I can dom but don’t do. I’m at the stage of conscious competence, in other words. I can drill the technique right, even use it when I’ve got it in mind during a roll.

When I need it most, when the problem that it addresses has just appeared out of nowhere? Then the technique isn’t to hand.

What’s the solution? Well right now I’m trying hard drilling and lower intensity sparring to bridge that gap and get some new techniques appearing reflexively in sparring.

My first gold since the HEMA Break, in the least serious or prestigious tournament possible. The May Melee ran a team relay, with each team of three fielding one fenced with a synthetic, one steel federschwert, and one steel one hander (not rapier).

Stefano (left, sabreur) was keen to win, and insisted I join his team. In revenge, I and our synthetic fighter Olly named the team “Pineapple Pizza”, after Stefano’s worst fear.

Stefano was disappointed by my performance, however. I was carried though the pools by the other two, who did well enough that we exited #1 into the semi finals, which were delayed until the next day.

I managed to sleep very well on Saturday night, largely based on exhaustedly collapsing fully dressed while searching my tent for beer tokens at 8pm. On Sunday my more competent fencing helped take us to two victories - finishing with me realising a 6-2 lead meant that I could double my way to winning.

Was it good fencing? No. Am I proud? No. Did it satisfy Stefano’s dragon-like lust for gold? For now.

Actual event review to follow.

“What do we say to the God of Rapiers?”

“Meh.”

I enjoyed yesterday’s training. It was the first class I’ve lead in ages, and it was structured very differently. Rather than “let me show you how I do X” or “the book says to do this when you want to X”, I went for “go do X and show me how you found works best”. A different way to approach teaching, but it seemed to meet the Fit, Fun, Functional goals pretty well.

I’ve got perhaps three more sessions of material in mind on the same theme of “inventing I.33”. Hopefully, we’ll start with basic premises such as:

- I want to hit someone with a sword [I’m likely to cut down from my dominant side]

- I want to protect my nearest targets from the other fencer’s sword [using the buckler to protect an extended sword arm is a good idea]

- If I stand there and cover a cut, there’s a risk of leg hits if they’re actually cutting low [Possibly ways to counter this are to immediately threaten a thrust off my cover, to retreat with the cover, or to make the legs a relatively less shallow target by hip hinging forwards]

And via sparring games/focused drills we’ll invent I.33. Hopefully.

The first session was extremely basic cuts, learning how an arming sword handles and coordinating it with buckler cover of the sword hand. We then introduced using the sword and/or buckler to cover a direct “caveman” head attack. It semi-organically led to a bind situation! Success!

Next session will be similar stuff on the other diagonal axis, and then thrusts and breaking them, going as far as schilt-schlach and stich-slach if we go fast.

I find that knowing the “why” makes a huge difference in the quality of repetitions - for example, the final drill we did of attack/counter-cut where one person is trying to cut to the head while not exposing the sword hand and the other is trying to cover the cut while likewise not exposing additional targets and lining up a thrust. It’s easier (in my brain anyway) to know what I want the technique to achieve and work to do that than to record a perfect and idealised form of it to mimic.

If you can handle his prose style, I have some good Luis Preto stick fighting books that discuss “ecological” training as superior to teaching forms.