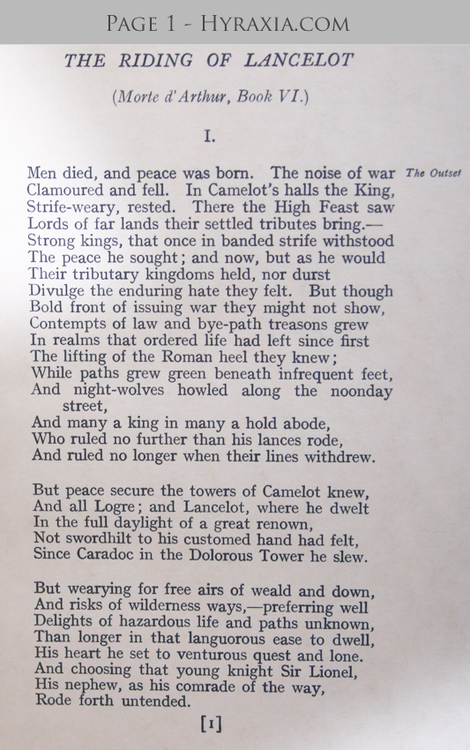

#le morte darthur

<sb> they asked really cliche job-interview questions.

<sb> “what is your biggest weakness”, etc.

<b> ugh.

<b> I"M ASCAIRT A GHOSE !!!!!!!

<b> “ok, fair enough. now, what do you consider your strongest point?”

<b> I POOP SO LONG I GOTS 2 STAND UP !!!!!!!!!!

<b> ptHThThThThHTthThT

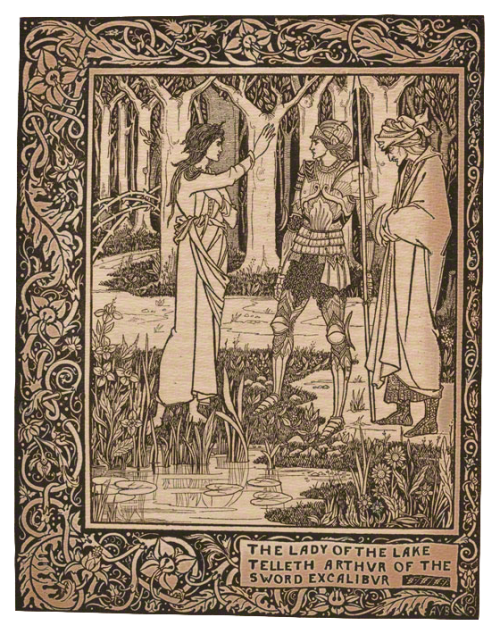

<b> LIKE PULLIN XCALIBUR OUT THA MOTHA FUCKIN STONE L@@K

<sb> whoso pulleth out this turd of this ass and butt is rightwise king born of all men’s rooms

<sb> (soundtrackbypsykosonik)

[ID: a digital portrait of a red-haired knight in filigreed black armor, framed by shining roses. His skull is partially visible through his face, and behind his head is a golden, decorated grail. The portrait is framed with symbols of the wheel of fortune at each corner. /ID]

Did it hurt? When you ascended to heaven?

This is my piece for the @arthurianum zine - please take a look at all the wonderful work (and get your copy today)! I’m honored to have been able to participate :)

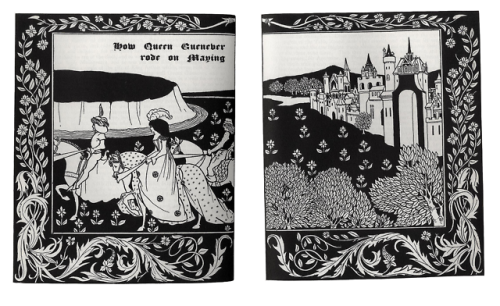

How Queen Guenever rode on Maying, Aubrey Beardsley, The Birth Life and Acts of King Arthur, of His Noble Knights of the Round Table, Their Marevllous Enquests and Adventures, the Achieving of the San Greal and in the End Le Morte D’Arthur with the Dolourous Death and Departing out of This World of Them All (Between p. 46 and p. 47), 1893-1894

Post link

The Lady of the Lake telleth Arthur of the Sword Excalibur, Aubrey Beardsley, The Birth Life and Acts of King Arthur, of His Noble Knights of the Round Table, Their Marevllous Enquests and Adventures, the Achieving of the San Greal and in the End Le Morte D’Arthur with the Dolourous Death and Departing out of This World of Them All (Between p. 46 and p. 47), 1893-1894

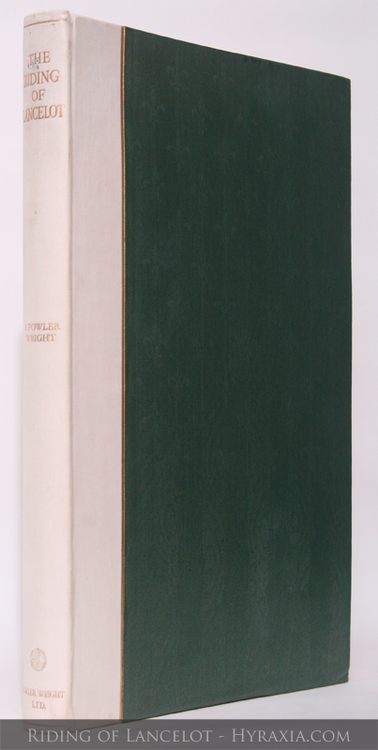

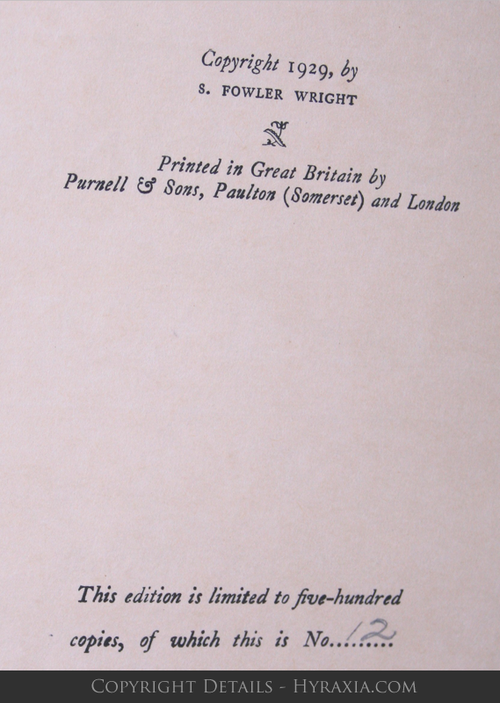

Source:Bauman Rare Books

Post link

today i am thinking about the episode “le morte d'arthur”, and how we really could have had it all

bear with me a moment.

what if, instead of the shit with hunith, it had been merlin’s life that had been taken in the bargain with nimueh. arthur wakes up, merlin says his goodbye, and by the next day, merlin is in bed with a high and delirious fever. arthur maybe doesn’t notice at first– he’s been lavished on by his father and those who thought he had been lost– but by the time he does–

“gaius,” he says, a grin on his face as he bursts through the door to the physician’s chambers, “i need merlin. father is throwing a victo–”

he pauses when he sees gaius in silent tears. he frowns, steps forward, sees–

merlin, on a cot. stock still.

arthur, a bit hysterical, walks over. “youre always sleeping, merlin,” he says, voice shaky.

“sire,” gaius starts, voice thick.

“no, he’s always– you act like it’s me that sleeps in, but you’re always–” his voice is cracking.

“he’s gone, sire.”

arthur demands to know what’s going on. merlin had been fine yesterday, and what does gaius mean, gone? what sickness could merlin have possibly gotten that could– that could–

gaius sits him down. he doesn’t want to tell arthur this, but the price has been paid for merlin already. there is little to fear about arthur’s retribution, now. he explains the isle of the blessed, of merlin’s sacrifice. he keeps out the fact that merlin has magic, just that he sought it out. by the end, arthur is livid.

“show me,” he says, already standing, “where it is.”

“sire, nimueh has powerful magic. you are no match–”

“as your future king. show me.”

gaius relents. arthur travels to the isle of the blessed without a second thought to what anyone else might think. he’s terrified. we see that. but he’s determined.

nimueh meets him with a smirk. “this is not the only life that has been traded for yours, arthur pendragon.”

this is where arthur finds out what happened with ygraine. by the end, arthur is furious beyond anything we’ve ever seen with him. he draws his sword– nimueh laughs, knocks it away with her magic, knocks him to his knees. “you will do well to think before you challenge me, boy.”

and arthur doesn’t know any incantations. doesn’t know any magic. but he puts his palms on the ground, the land that is his as much as he is its. begs, quietly. swears that he will do better, be better than his father. that he will bring its magic back.

when he looks up, there are vines surrounding nimueh. she cannot get out of their entanglement, though she tries her best. arthur picks up his sword. the rain starts. tears streaming down his face and eyes gold, he runs her through.

when he returns, gwen meets him. “arthur, you’ll never– merlin is–”

he runs to him. merlin is confused, and awake, and alive. even more confused when arthur hugs him.

“what happened?” merlin asks.

and because this is the end of the season, arthur lies. says he doesn’t know, but merlin is safe and that’s all that matters. “you live to serve me another day, merlin,” he jokes.

the second to last scene is arthur with his father. he demands of him to tell him why he banned magic. his father states the carefully constructed lie he’s heard all his life. “why do you ask, arthur?”

arthur sets his jaw. he’s seen through it now. “nothing, father.”

“get your rest.”

the last scene is arthur returning to gaius’. merlin is asleep, gaius explains. he needs his rest. but arthur is not here for merlin. he’s here for gaius.

gaius asks him as calm as he can. “what happened there? on the isle of the blessed?”

arthur shakes his head. that’s a story for another time.

“gaius,” he says, hands shaking. “i think i have magic.”

–

(and then we would get a season of arthur grappling with that privately, keeping appearances publicly, and all the while still oblivious of merlins magic. he also struggles with the fact that merlin negotiated with nimueh, his father’s secret, and everything else. morgana still grows bitter because arthur keeps his shifting opinion on magic secret. fill in the rest.)

anyway yeah. we could have had it all, yall.