#s fowler wright

The Riding of Lancelot is Sydney Fowler Wright’s take on a scene from Arthurian mythology. But before we look into the book itself let’s look at the source material. King Arthur’s as old as Britain, his story stretches back fifteen centuries and has never perhaps been as vibrant as in the last century. Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae [The History of the Kings of Britain] introduced him to the English via Latin from the Welsh in the first half of the 12th Century. Now don’t assume that a grand title such as this book has would suggest a good place to look into early English Arthurian sources, because Monmouth’s book was one of the original works of alternative history wherein he peppered his history with elements of credible fantasy. Geoffrey introduced to the canon Merlin, Excalibur and Guinevere - that’s not to say they were his creation, but the written word being what it was, his was the first detailed recording in this form (with early fantasy literature it’s better to think of a web than a timeline, each author adding his own spin). Chretien de Troyes, a French writer from around the same time, plugged in Lancelot and the holy grail. But it wasn’t until the 15th century that the mythology found an expansive story in Thomas Malory.

In a similar way to how Tolkien gathered together northern European mythology in Lord of the Rings, Thomas Malory gathered Arthurian legend.The book was originally intended to be titled The Whole Book of King Arthur and of His Noble Knights of the Round Table, but was retitled Le Morte D'Arthur [The Death of Arthur] and was one of the first books printed in England (by William Caxton), an ode to its importance if ever there were one. The earliest obtainable copies of the book come from 1634, which was at least the sixth edition of the book and nearly 150 years more recent than Caxton’s printing from 1485. None of the intervening editions are likely to come to market (an early 16th century fragment came to the market in the early 1970s). The British Library own a manuscript from a few years before Caxton’s printing. I mention this printing history largely because the books go through new translations, have material added to them and get edited and even rewritten. Each iteration of the story alters the cultural landscape a little, adds a new gem, or omits something that offers food for thought.

It’s important to consider the conditions under which a book is written and published, the writer’s education, first language, social standing etc. because all these things affect the writer’s bias and interpretation of the folklore they’re they’re trying stabilise. For Malory this is particularly important. He could quite easily have been from Westeros, his claims included being a knight of the shire, a member of parliament, being fluent in both French and English, reasonably well educated and somewhat wealthy. But toward the end of his life he took a violent turn and his claims included extortionist, horse thief, general thief and rapist. He even broke out of prison and was involved in subterfuge in the Wars of the Roses. He was ultimately jailed though, and it was in jail that he wrote Le Morte. Like I say, Westeros would suit him well. Now if you take a person like that and get them to write a book, particularly a book on something they have first hand knowledge from both the moral and amoral sides, then you end up with something that lasts five hundred years.

Anyway, we’re getting into too deep a history, so let’s get back to Fowler Wright’s book. It’s sufficient to know at this point that Malory's Le Morte D'Arthur is kind of the first version of the Arthurian legend that we’re all familiar with and for the 500 years or so that it’s been in print it’s been an invaluable source for many, if not most, of the subsequent interpretations.

S. Fowler Wright was a fairly prolific writer, particularly of science fiction and was one of a handful of British writers to fill that gap of gestation between Verne and Wells and the forthcoming wave of golden age science fiction from the US. He’s largely forgotten today, but there are readers out there still. His first published work was another Arthurian work, published ten years before the present work. Reading through various biographies it would appear that Fowler Wright was a strongly moral man. Now a comparison between himself and Malory isn’t really applicable, but one can assume that the vantage points were quite different, and thus their rendering of the myth would be quite different.

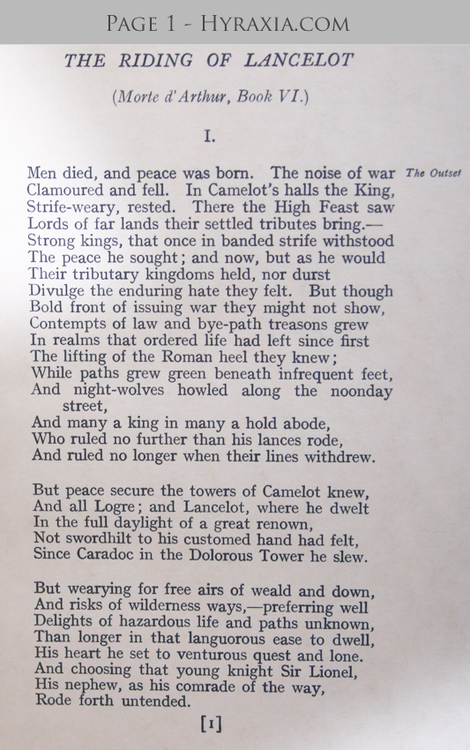

The book itself is a joy to read, within the first five pages there’s action involving knights, a chase scene between knights, a fight between knights, a castle containing a knight and a forest with a knight (bloody Lancelot sleeps through the whole thing). I think that’s more than Robert Jordan put in entire books. As the book is a poem you take the pace of reading somewhat more carefully, parsing each sentence slowly and deliberately within the structure, but the image that is created is very similar. The flow and rhythm of the book brings you very much into the scene. The story itself is quite faithful to its source, Wright has even used iambic pentameter as did Malory. it is drawn from book six of Le Morte with a few minor characters replaced with more familiar ones. Wright also rounds the story off a little at the end by adding a kiss with Guenevere. On top of this, there’s something quite special about reading a book that’s this old and quite well presented. It undoubtedly adds to the reading experience to think you’re reading the story as it was first read a hundred years ago.

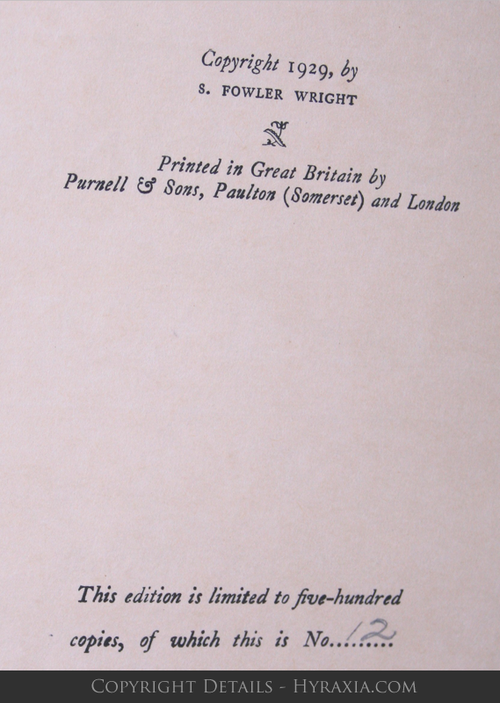

It’s difficult to say how this book in particular contributed to the current snapshot of fantasy literature; it is absent from many bibliographies, present in only a handful of academic institutions, scarce and out of print. And since the book is out of print and has been since Wright self-published this with a print run of 500 copies in 1929 it’s tricky to find. I’m aware that I’m building the book up just to say that you can’t read it, this isn’t my intention. Rather, I would hope you might take away the impression that next time you’re in a bookshop and you see an old leather bound tome with a somewhat intriguing title then buy it (obviously only if they’re not overly expensive for the gamble), you might be surprised. I have attached the first few pages, which I urge you all to read, just so you can get an impression of the landscape.

So, why am I writing about a virtually unobtainable book, something by virtue of the fact that it’s written by a forgotten author and is out of print is evidently unimportant? Well, because it should be remembered. This interpretation is a good one, and by studying it we are keeping it fresh in the collective mind of fantasy. It is an important work in the Arthurian oeuvre and deserves a bit of attention. But I don’t bring it here to tell you just how important it is or its history, I bring it here to illustrate the point that to find good fantasy doesn’t always mean sitting and waiting for the publishers to show you a pre-publication trailer of a new book, or even believing the hype. No, there are stories out there, good stories that have survived millennia, stories that take a bit of hunting to find and a bit of time to read, but stories that are rewarding. We talk about the changing landscape of fantasy, but we can’t truly appreciate this without looking at the history of it.

I read a list recently of the 25 greatest fantasy novels. The vast majority of books on the list were first published in the last 20 years. Now while it’s unlikely that the fantasy published in the last two decades represents 90% or more of the best fantasy of all time, it is understandable why this list appeared as it did; most of the stuff readers buy is new stuff, so there’s a bias toward that. There is of course the angle that the literature that is published now builds upon all that has come before it so has the advantage of a good palette of colours. However, fantasy, being the oldest form of literature is an incredibly rich and varied canon, and it would be a shame to think that not enough people are digging deeper.

As rare booksellers we generally look for books that have contributed to the cultural landscape. It helps us feel that our job is more than just buying and selling. Most books from the last couple of decades haven’t had the chance to contribute fully, or rather their contribution hasn’t yet been fully realised. So the majority of our stock is pre-21st-century. There are some exceptions where the cultural impact is undeniable (Pratchett, Martin, King, Rowling) or where the books have helped progress the variety and strength of the canon (Hobb, Mieville, Abercrombie), but on the whole the fantasy literature we deem ‘important’ has had at least a generation to permeate the cultural membrane.

Of course, important and great aren’t necessarily the same and it takes a lifetime to reconcile the two. A lot of the time we read what we feel is entertaining, because we aren’t always interested in how it impacted the canon. There’s nothing wrong with that. But at the same time, there is a lot of important writing out there that is great (there is also important writing that’s bloody boring). I’m thinking of writers like William Morris, E.T.A. Hoffman, E.R. Eddison, Edmund Spenser, Thomas Malory, and pieces such as Beowulf, Gilgamesh, The Odyssey, The Mabinogion. These are writers and works that have had an incalculable influence on the books of the last 20 years, and continue to do so.

I am slightly biased toward this area of fantasy because these are the scarcer items and these are the items that collectors buy because of their importance within the canon, so they are good stock. But at the same time, in my research and reading I’ve found these to be great and entertaining reads. So I thought I’d write some pieces based around rare books and important works of speculative fiction (i.e. fantasy, science fiction and horror) that are more often seen in university libraries than in the Waterstone’s fantasy section.

I’ll be looking at publication history, cultural impact, various rarities, reading strategies and I encourage you to comment too because I imagine many of you have much more experience in these areas than I do. Many of the books will be new books we’ve just acquired, and many we’ll have little knowledge of, so it will be a learning experience. And if just one of you picks up We’ll start by looking at S. Fowler Wright's The Riding of Lancelot.