#liv ullmann

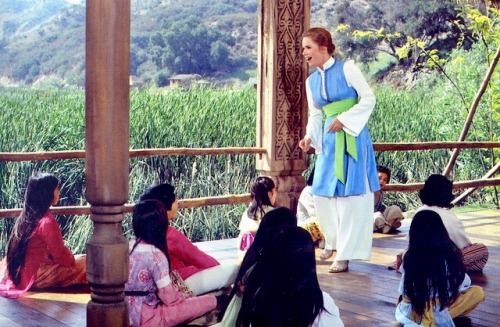

Cinematography of Persona (1966) and Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019)

Women on the run.

Films in Frame - Persona, Potrait of the Lady on Fire, Licorice Pizza, The Worst Person in the World, Spencer, The Double Life of Veronique, Little Women, Frances Ha, Fleabag, Run Lola Run

Faye Dunaway at the Beverly Hills Hotel | Terry O’Neill, 1977

Winning never looked so lonely.

Exterior, early morning. Newspapers, scattered across an empty pool terrace. A solitary woman, slumped in a lounge chair, stares bleakly past the Oscar statuette on the table by her side.

If the set-up feels like a movie mise-en-scène, then that’s quite probably how the participants intended it. In the run up the 1977 Oscars, Faye Dunaway had quickly emerged as Best Actress front-runner for her dazzling turn as Diana, the mercenary TV executive in Sidney Lumet’s Network. Up against Liv Ullmann, Sissy Spacek, Talia Shire and Marie-Christine Barrault, she didn’t have high expectations: she’d been nominated, and lost, twice before (to Katharine Hepburn in 1967, and then to Ellen Burstyn in 1974).

And Dunaway had never won anything, really; had always been the runner-up, the second choice, the understudy - ever since she’d placed an unspectacular second in the Miss University of Florida pageant back in 1959. She wasn’t even been the automatic choice for Network: as with Chinatown, the role was a cast-off from Jane Fonda. On the night, standing on stage at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in her loose Geoffrey Beene two-piece, her acceptance speech started equivocally: “Well, I didn’t expect this to happen quite yet …”

Dunaway and photographer Terry O’Neill had first met six years earlier, on the set of the revisionist Western Doc in Spain: then, Dunaway had been nearing the end of a relationship with Marcello Mastroianni. In January of 1977, with Dunaway now married to musician Peter Wolf, they’d crossed paths again. This time the meeting was at the actress’ home in Boston, where O’Neill shot her for a People cover story which hit newsstands on the morning of the Oscars, headlined Will She Win The Big O?

As the buzz had grown around Dunaway in the weeks after the nominations were announced, several photographers had approached her to pitch ideas a victory shot. But a few days beforehand, she’d agreed to go with O’Neill’s idea of a morning-after shot to run alongside a Michael Parkinson interview in the Sunday Times - capturing, not the moment of victory, but the reality of its aftermath. Photographed poolside at the Beverly Hills Hotel (where Dunaway, and Wolf, and half of Hollywood, were staying that week), and wearing a copy of the satin monogrammed bathrobe she’d famously worn as Evelyn Mulwray in Chinatown, she was triumphant and abandoned: a queen, but of an empty kingdom.

It was the end of an extraordinary month in Hollywood. 1977, in several ways, represented a significant changing of the guard between generations. The city’s silver screen legends - Mae West, Bob Hope, Mitzi Gaynor, Loretta Young - were still about, in some force. But the new generation (Nicholson, Hopper, Rowlands, Cassavetes, plus second-generation stars like Jane Fonda or Anjelica Huston) were becoming increasingly dominant. There was an influx of European stars, like Jeanne Moreau (recently married to William Friedkin, the man responsible for directing the Oscars that year), Lina Wertmuller and Isabelle Huppert - and an ambitious Austrian bodybuilder called Arnold Schwarzenegger, who against all odds had won Best Newcomer at the Golden Globes that January. And there were the bystanders and onlookers - Diana Vreeland and her granddaughter Phoebe, sports star Joe Namath, singer Tom Jones.

They had plenty to talk about. Not just the Oscar nominations themselves (a notably eclectic line-up, with another outsider - the boxing movieRocky, written by and starring a cocky New Yorker called Sylvester Stallone - tying with Network for 10 nominations. (An eclectic list, but not a diverse one: on the night, demonstrators outside the pavilion would protest against the absence of black nominees - whilst inside, co-host Richard Pryor delivered a monologue starting “I am here tonight to explain why black people will never be nominated for anything…“) There was drama over the ceremony itself, which Friedkin had stripped back to basics: “People said the Oscars would never survive without Bob Hope.” designer Bob Mackie said, after quitting the show in protest. “Now let’s see if they can survive without glamour.”

Down the coast, at a secluded beachfront house in Monarch Bay, disgraced former president Richard Nixon was locked in a tense series of interviews with David Frost (whilst the film about the investigation which had precipitated his undoing, All The President’s Men, kept his activities in the headlines). Andy Warhol was in town, celebrating what would be his final film - Jed Johnson’s Bad. And to top it all, two weeks earlier, Roman Polanski had been arrested in the lobby of the Beverley Wiltshire on suspicion of rape, sodomy, child molestation and giving dangerous drugs to a minor. The incident had taken place at Jack Nicholson’s house off Mulholland Drive: Anjelica Huston, Nicholson’s on again/off again girlfriend, was caught up in the aftershock, arraigned on possession charges after police found cocaine at the property.

On the night of the Oscars themselves, despite Friedkin’s best efforts, the show had overrun. The Governor’s Ball, a black-and-white spectacle held at the Hilton, had gone on till the small hours of the morning. Dunaway’s two-piece had been swapped for the t-shirt her husband had made up for her, screen-printed with the words: ALL THE WAY WITH FAYE. Even on the night, though, her victory hadn’t been the big story - that honour had been split between Stallone, who’d lost Best Actor (“If it’s not this year, it will be next year.” he’d told reporters bullishly backstage), and Peter Finch, who’d posthumously won. (Finch had dropped dead in the lobby of the Beverly Hills Hilton two months before).

But for now, at least in front of O’Neill’s lens, Dunaway was the undisputed star of the show. She’d just signed a deal to star in Jon Peters’ The Eyes of Laura Mars, and her fee had gone up to a million dollars a movie. In the shot the Times eventually used - not the one which has gone down in history - the breakfast tray and dressing gown have gone. The actress sits bolt-upright and wary, in a cream trouser suit and heels, clutching Walker Percy’s 1971 satire, Love In The Ruins. In the middle of her autobiography, Looking for Gatsby, Dunaway recalls the shoot: ‘It looks to be just after sunrise, but thankfully it was shot much later in the day.’

But by then, the ‘morning after’ shot had already become entrenched in Hollywood myth. And by then, no-one was paying much attention to Dunaway any more. After Network, she’d struggled to maintain momentum: The Eyes of Laura Mars was followed by movies like Mommie Dearest andSupergirl, which pushed her further and further into caricature. Her reputation as a difficult, often volatile collaborator worse and worse. In 2003, O’Neill came forward to admit that the Liam, the son they’d had together 20 years earlier, was adopted. So if Dunaway could fudge the truth on that, why should she be any more reliable on the time of day a photograph was taken?

But the shadows give it away. Look up to the top third of the frame. Just along the left hand rim, there are long, low slices of light and shade cutting into the side range of the Beverly Hills Hotel. That light is cast from over the boundary wall with Hartford Way, as it spills across Sunset Boulevard and into Rodeo Drive; light which was coming not from the morning east, but from the west, where the sun was lowering into a Pacific horizon.

Roman Polanski had spent the day somewhere out in that western light, in a Santa Monica courtroom. His alleged victim had testified a few days earlier, and the proceedings which would soon lead to his permanent departure from the US were underway. In a surreal twist, a horde of teenage schoolgirls had found out his location, and chased him through the building with their autograph books. (In another, sadder twist, Manson Family member Leslie Van Houten was also in the courthouse that day, applying for one of many appeals to have her conviction for her part in the death of Polanski’s wife, Sharon Tate, overturned).

On Oscar night itself, Polanski’s name hadn’t been mentioned (although beforehand, an agent had made the bizarre suggestion of teaming him up with child star Tatum O’Neal to present an award). The film he’d been preparing for, The First Deadly Sin, went into a long production limbo. Anjelica Huston moved out of Nicholson’s home, and in with Ryan O’Neal: Nicholson tersely told reporters he’d be ensuring that no visitors would use his property again. And for now, the rest of Hollywood closed ranks.

But something had been broken. New Hollywood - independent, challenging, provocative - was irretrievably damaged. The coming decade would see that independence replaced by nostalgia and gung-ho patriotism, by PG-rated franchises like Star Wars and Indiana Jones. And Dunaway’s gaze was east, away from all of that. She and Polanski had never got on particularly well; he’d cheerfully labelled her a ‘gigantic pain in the ass’, and the Chinatown shoot had been a deeply bruising experience. And the papers surrounding her in O'Neill’s set-up had to be carefully folded to focus on the Oscars. Like it or not, the day’s headlines belonged to Polanski, not her. The world had already moved on. Dunaway’s moment in the sun, like the day itself, was almost over.

Darrach, Brad Will She Win The Big O?, People Magazine, 1977

http://www.people.com/people/archive/article/0,,20067582,00.html

Dunaway, Faye Looking for Gatsby: My Life, 1998 (with Betsy Sharkey)

http://www.worldcat.org/title/looking-for-gatsby-my-life/oclc/32970016&referer=brief_results

Hunter, Allan Faye Dunaway, 1986

http://www.worldcat.org/title/faye-dunaway/oclc/13643667&referer=brief_results

Jacobs, Jody

Kiernan, Thomas Repulsion: The Life and Times of Roman Polanski, 1981

http://www.worldcat.org/title/repulsion-the-life-and-times-of-roman-polanski/oclc/16564253&referer=brief_results

Kilday, Gregg Outtakes from an Oscarcast, The Los Angeles Times, 1977

http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/latimes

Morrison, James Hollywood Reborn: Movie Stars of the 1970s, 2010

http://www.worldcat.org/title/hollywood-reborn-movie-stars-of-the-1970s/oclc/659579856&referer=brief_results

Parkinson, Michael Faye as a Runaway, The Sunday Times Magazine, 1977

Rose, George Hollywood, Beverly Hills & Other Perversities: Pop Culture of the 1970s and 1980s, 2008

http://www.worldcat.org/title/hollywood-beverly-hills-other-perversities-pop-culture-of-the-1970s-and-1980s/oclc/190621292&referer=brief_results

Zenovich, Marina Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired

http://www.imdb.co.uk/title/tt1157705/

Faye Dunaway at the Beverly Hills Hotel | Contact Sheet, Terry O’Neill, 1977

“…You and I are so alike.

You mean in our selfishness, coldness and indifference?”

Cries and Whispers (1972), Ingmar Bergman

Persona (1966)

dir. Ingmar Bergman.

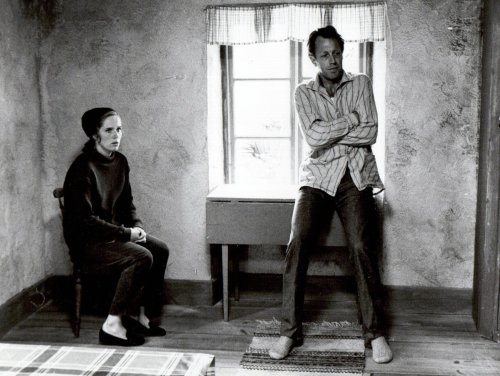

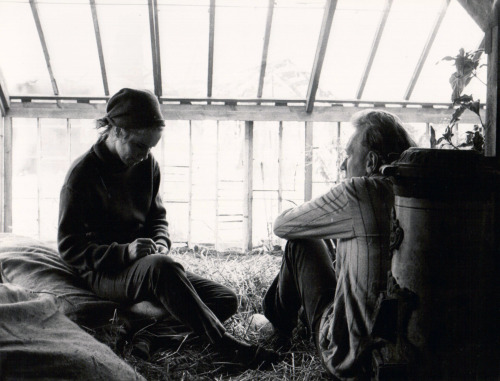

Scenes from a Marriage (1974)

Directed by Ingmar Bergman

Cinematography by Sven Nykvist

“We were not in love. On the contrary, we were sad.”

Post link

“… kalbim seni özlüyor.”

“But here, at Shangri–La, all was in deep calm. In a moonless sky the stars were lit to the full, and a pale blue sheen lay upon the dome of Karakal”

Post link