#maundy thursday

HOMILY for Maundy Thursday

Ex 12:1-8, 11-14; Ps 116; 1 Cor 11:23-26; Jn 13:1-15

“Father, why is this night different from other nights?” According to Jewish tradition, this was the question that the youngest child would ask his elders on Passover night, in the middle of their meal. And then his father would tell the story of Israel’s salvation, and recall the account from Exodus that was read to us tonight, how God saved the people of Israel by passing over the houses of the Jewish people, which they had marked the lintels with the blood of the sacrificed lamb, having carried out the detailed instructions given to them concerning the selection of the “lamb without blemish”, the time and manner it was to be slaughtered, and then the way it was to be cooked – by being stretched between two wooden sticks so as to be roasted over a fire – and then eaten albeit in haste.

The first Passover, then, wasn’t so much a celebratory meal, although the eating of the roasted lamb was important to complete the ritual action. Rather, it was a ritual sacrifice, thus attention was paid to the selection of the sacrificial lamb, its preparation and so on. At the time of Jesus, things had developed. Now that the annual Passover commemoration was being celebrated in the Promised Land (and not in Egypt), so the chosen lamb had to be brought to the Temple, which was on Mount Sion, and it had to be sacrificed in the Temple by the priests. They then had to eat the lamb, but not in their own home as such: You had to eat it in the city of Jerusalem so if you weren’t a local resident you either rented a room for your Passover meal, or went to the house of a friend or benefactor who lived in Jerusalem. And this is what Jesus did: it is believed that the Upper Room in Jerusalem where he celebrated the Last Supper probably belonged to the family of St Mark the evangelist, or Nicodemus.

However, we’re so accustomed to calling this the Last Supper or the Lord’s Supper that we’ve becoming used to thinking of the Passover as being principally a meal. However that is not how Scripture understands it. The book of Deuteronomy, for example, refers to it as the “Passover sacrifice”. And nobody who was in Jerusalem on the days of preparation could have ignored this fact. For according to the historian Josephus over two hundred thousand lambs were slain for the Passover in Jerusalem; the Temple would basically become like an abattoir, and the priests were like butchers carrying out this specialised ritual act of sacrifice. The sacrificial aspect of the Passover, therefore, predominates in the mind of the Jewish people, and so Jesus thus speaks of his own death of Calvary in a sacrificial manner, and from the very beginning of St John’s Gospel, Christ is highlighted as the Passover lamb, perfect and unblemished, and he is taken to Calvary at the very hour that the lambs are being sacrificed in the Temple. St Paul, therefore, would later write that “Christ our Passover lamb has been sacrificed.” (1 Cor 5:7)

So, we might ask tonight: “Why is this meal different from other meals?” and the answer is that the Passover was no ordinary meal – this was not just a community meal or like any other convivial family gathering. The Passover was a liturgical action, a ritual sacrifice which, as we heard in the reading from Exodus, was to be solemnly commemorated every year so that God’s people could remember their deliverance from death in Egypt and also from slavery to Pharaoh. The Passover, therefore, celebrated the liberation of God’s people from ancient tyrants including Death itself. It was within the context of the Passover, then, that Jesus takes up these Jewish understandings of the Passover, and then, as the long-awaited Messiah, he transforms them and inaugurates a new Passover, a new Exodus, a new Covenant.

With all this background, then, we can now ask: “Why is this Passover that Christ celebrated the night before he died different from other Passovers?” Firstly, it seems that the apostles did not go to the Temple to offer the sacrificial lamb. Rather, they gathered for the Passover in the Upper Room, and then Jesus declares himself to be the true sacrifice, the definitive Passover Lamb. The way he does this is by declaring the bread and wine to be his Body and Blood so that the focus of the meal is not the body of a lamb that had been slain in the Temple but rather his Body, his Blood which was to be poured out in sacrifice, slain on the Altar of the Cross the next day. Christ is saying, in effect, “I am the new Passover lamb of the new Exodus. This is the Passover of the Messiah, and I am the new sacrifice.”

He then commands his apostles to “Do this as a memorial of me”, as St Paul recounts in the second reading. This deliberately echoes the command of God in Exodus to celebrate the Passover as a memorial in honour of God and his saving work. So, now, Christ commands that the new Passover be celebrated in memory of Christ who has rescued us from the tyranny of sin and from eternal death through his Sacrifice on the Cross. The new Passover, which we call the Mass or the Eucharist, is that ritual sacrifice, that liturgical action commanded by Christ on this night to remember the saving and redeeming and liberating sacrifice of Christ on the Cross. Hence St Paul says: “Every time you eat this bread and drink this cup, you are proclaiming his death.” And it is by Christ’s death that you and I, we Christians, have been liberated from the tyranny of Death itself.

Therefore, we might ask: “Why is the Mass, at which we eat and drink, different from all other meals?” What is actually happening in the Mass which was instituted by Christ on this night? The answer is that, like the Passover of the Old Covenant, so the Passover of the New Covenant, our familial bond with God that has been ratified by the Blood of Christ, is no mere family meal. Rather, it is first of all a ritual sacrifice, which is why we rightly speak of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. This is also why we do not just gather around a table for the Mass but, more properly, we go up to the Altar, which means the high place, where the Sacrificial Lamb of God is offered and immolated. So, later on, by going up to the High Altar, it is like going up Mount Sion to the Temple, where, at the Altar, the Priest offers Christ, the true Passover Lamb to God. Then, at Holy Communion, the Lamb that has been offered in sacrifice is brought from the Altar, as if from the Temple, and given to the people and it is eaten, not in your own homes, but here within the church, that is to say, within the walls of the new Jerusalem. As such, we can see that what we do in this Mass and in every Mass is rooted in the ritual sacrifice of the Jewish Passover, but also transformed and renewed by Jesus Christ.

For the biggest difference is the fact that the sacrificial Lamb is present and is eaten but the Lamb is hidden under the appearances of bread and wine; Christ is truly and substantially present though under these sacramental forms. Why? St Thomas Aquinas suggests that Christ does this to mercifully spare us the shock and horror of seeing his bloody death on the Cross every time we come to Mass. Nevertheless, lest we forget and fall into the trap of thinking that the Mass is just a community gathering to celebrate our faith, or that we gather mainly for a service of the Word, the Council of Trent states plainly: “that same [Jesus] Christ who once offered Himself in a bloody manner on the altar of the cross is [now] contained and immolated in an unbloody manner” on the altar of the Holy Mass.

Finally, we might ask: Why is bread and wine offered? Unleavened bread was already part of the first Passover, and as Christ says in John 6, it is also a reminder of the manna from heaven which was kept in the Holy of Holies of the Temple, and of the mysterious Bread of the Presence that was offered in sacrifice in the Temple. Wine came to be included as part of the Passover ritual, and by the time of Christ, four cups of wine were drunk at important points in the Passover ceremonial. But intriguingly, Christ does not drink the fourth cup during the Passover meal. Rather, he delays it until his final moments on the Cross. Then, St John says, “When Jesus had received the wine, he said: ‘It is accomplished’”. By doing this, Christ links his Sacrifice on the Cross, which accomplished the salvation of the world, liberating all humanity from sin and death, to the new Passover at which he inaugurated the Sacrifice of the Mass. Therefore, whenever we come to Mass, and whenever we eat and drink his Body and Blood in Holy Communion, we fulfill Christ’s command to remember his saving death that has opened the way to eternal life for us.

How wonderful is this holy Sacrifice of the Mass, this “sacred banquet in which Christ is received, the memory of His Passion is renewed, the mind is filled with grace, and a pledge of future glory is given to us.” Truly as the Gospel says, through the Mass and everything he did on this night, Christ “showed how perfect his love was”, and he gives us the means, the Eucharist, to empower us to love others as he has loved us.

Today is »Maundy Thursday«. In German it is called »Gründonnerstag« (literally: »Green Thursday«) and the Swedish name for the fifth day in the Holy Week is »Skärtorsdagen« (lit.: »The Clean Thursday«).

Where does the differences come from?

The English term »Maundy« derives from the Latin word »Mandatum« and is a religious rite where one washes the feet of someone. This rite is described in the Bible by several disciples who observed Jesus washing the feet of the twelve apostles before the Last Supper.

The Swedish word »skär« is an old nordic term and has been used to describe something as »clean, nice, white«. The origin is the same as in English.

How come, the German call the day »Green Thursday«?

There are several explanations that can be found—unfortunately no one can say what the correct one is.

- Today is the day where the sinners get their sins freed by the church. The Bible describes this rite metaphoric as a part to recover as »green wood«. For this occasion members of the church wore white dresses often with green ribbons.

- Another explanation is, that there is still the period of fasting and that the Christians eat especially green food like vegetables, green cabbage and salad. Furthermore it has been the day where the spring often begins and the people tilled their fields.

- A third explanation is that »grün« does not really describe the color green but rather derives from »greinen« which means crying and refers to being sad because of Jesus’ coming death.

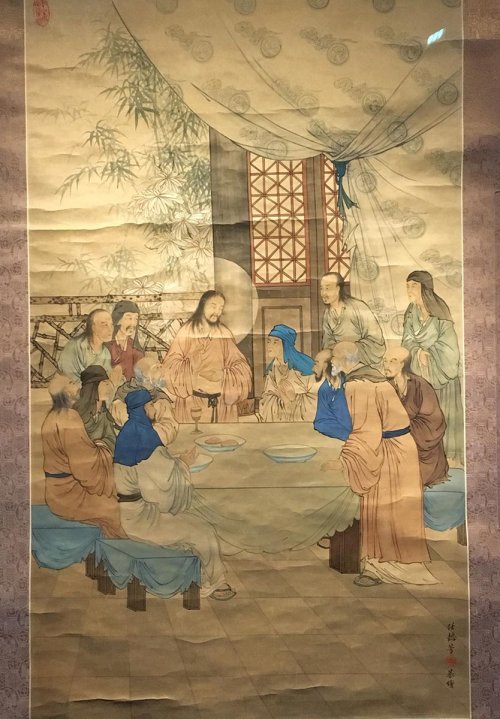

Photo: harry_nl: https://flic.kr/p/6T4jqP

Post link

Mandátum novum do vobis: ut diligátis ínvicem, sicut diléxi vos, dicit Dóminus.

A new commandment I give unto you: That you love one another, as I have loved you, saith the Lord.

Post link

Et cum facta esset hora, discúbuit, et duódecim Apóstoli cum eo. Et ait illis: Desidério desiderávi hoc pascha manducáre vobíscum, ántequam pátiar.

And when the hour was come, He sat down: and the twelve apostles with Him. And He saith to them: With desire I have desired to eat this pasch with you, before I suffer.

Luc. XXII, 14-15

Post link

In that same night, then, when men were thinking of preparing torments and death for Jesus, our beloved Redeemer thought of leaving them himself in the Blessed Sacrament; giving us thereby to understand that his love was so great that, instead of being cooled by so many injuries, it was then more than ever yearning towards us.

O love of my soul, most Holy Sacrament; oh that I could always remember Thee, to forget everything else, and that I could love Thee alone without interruption and without reserve!

St. Alphonsus Liguori

Post link