Save Me From Myself

Author: kjack89

Art by jeanenjolras

Pairing(s): Combeferre/Grantaire, Enjolras/Grantaire

Warnings:Alcoholism, recovery, relapse; brief emetophobia; canonical major character death

Summary:Combeferre seeks to free Grantaire from the chains on his dependence on alcohol, no matter if he may have a dual motivation in mind. But just when things seem to be going better than Combeferre could have hoped between them, the events of June 1832 happen.

Notes:Much thanks to Pilf for allowing me to not so much bend as outright break the rules on word limit here, and to Perry for agreeing to this beast. As with everything I write of this nature, anything I say or imply about addiction, recovery and relapse are based on my own experiences and should not be taken as universal. Most of the recovery itself takes place offscreen, due to the sometimes graphic nature of detox that could have bumped this out of T territory. As this fic is over 5000 words long, it will be cut off if read on Tumblr mobile.

Combeferre let out a world-weary sigh before opening the door to the modest suite of rooms he called his own. It had been almost three days since he had last slept in his own bed, and judging by the ache in his back and the numbness that had stolen over his mind as he journeyed through the near-empty streets of Paris, he longed for it dearly.

But sleep was not to be achieved, at least not immediately, as Combeferre opened the door to find a fire lit in his grate and Courfeyrac lounging on his méridienne, sipping from a glass of wine. “Ah, Combeferre!” Courfeyrac said loudly, sitting up and raising his glass as if toasting his return. “I hope you do not mind I helped myself. Awaiting your return when you left no word as to where you’d gone was thirsty work.”

If it were not for the fact that Combeferre and Courfeyrac had been close friends for years, Combeferre might have taken Courfeyrac’s words at face value. As it was, he read the worry hidden in his tone and saw the shadows that lingered under Courfeyrac’s eyes, not quite masked by the brightly-colored waistcoat and cravat clearly chosen to make Courfeyrac look less peaked, and surmised that he had not been the only one with a few sleepless nights under his belt. “You were awaiting my return?” he asked mildly. “Surely when you had entered my chambers and discovered my absence, you should have taken your leave.”

“I did,” Courfeyrac acknowledged steadily. “But not after trying to ascertain your whereabouts, and upon discovering no one knew where you had gone, I endeavored to wait for you here. Granted, I did not imagine it would take you this long to return…”

His words held no condemnation in them, only mild curiosity, but Combeferre flushed and said quickly, “I was with Grantaire.”

There was a moment of silence before Courfeyrac said in a low voice, “Ah.”

That simple syllable held a world of emotions and discussions between the two men, and Combeferre bristled at the assumed accusation. “He has endeavored to give up alcohol,” Combeferre told Courfeyrac, sighing heavily, for this was a topic that he and Courfeyrac had discussed — at least a topic they had discussed in theory — many times before. “And he grew ill from doing so. His body has grown dependent on the alcohol and in its absence…”

He trailed off, hoping that Courfeyrac would understand, but instead Courfeyrac’s brow furrowed. “If Grantaire was ill, you should have called for a doctor,” he said lightly. “Joly, perhaps, if a real physician was not to be trusted. Surely as much as I am sure Grantaire appreciated you nursing him to health, there were other alternatives to you sitting by his bedside.”

“Even if there were, what need was there for an alternative?” Combeferre asked, matching Courfeyrac’s assumed levity. “Grantaire is our friend, and as I was free to sit by his side and ensure he did not die from convulsions or hurt himself in his hallucinations, why should I not have done so?”

Courfeyrac’s brow furrowed. “Because I do not believe you are doing so for the right reasons.”

Combeferre sighed and loosened his cravat as he slumped into the chair by the fireplace. “And what would you deem the right reasons? To free our friend from the hold that alcohol has over him, with the research that I have done into dipsomania, what better reason exists than that?”

“And what of Enjolras?”

Combeferre seemed taken aback by the question. “What ofEnjolras?”

Courfeyrac set his glass of wine down on the table, running his finger lightly down the stem. “If, hypothetically, you were assisting a mutual friend of ours in hopes that under different circumstances, happier and more complete in himself, he might catch the eye of our Noble Leader, that could be considered…honorable of you,” he said, carefully. “If you were assisting a mutual friend in hopes that he might instead discover similar feelings to your own, then that is another matter entirely.”

For a moment, it seemed that Combeferre would deny that sentiment outright, but instead, he reached for the bottle of wine and spare glass that Courfeyrac had thoughtfully left out. “You do not know of what you speak,” he muttered.

“Don’t I?” Courfeyrac leaned forward, his expression troubled. “You and I sat in this very room, splitting a bottle of wine much like on this night — or on this morn, I suppose, given the hour — and you confessed that you wished to help Grantaire, wished to assist him become a man free from alcohol and thus hopefully catch more than disdain from Enjolras. You thought it was a plan in which they could both be happy, and I do not question that motive. You and I have known for a long time that there is something good that could transpire between Enjolras and Grantaire if only they could both manage it. But I question whether you will be happy, if your plan succeeds, if Enjolras spares a second thought to our beloved libertine.”

Combeferre shrugged and took a sip from his glass of wine. “I will be happy if Grantaire is happy,” he said quietly.

Courfeyrac studied him for a long moment, then hoisted his own glass and said, a little gravely, “I truly hope that you will be”, before draining his wine. Combeferre took a moment before draining his glass as well, the wine sticking in his throat the way that the lie just uttered by his lips had not.

——————————

It had been two weeks previous when this all had began — not counting the conversation Courfeyrac had mentioned, which had taken place long past, under the influence of lofty ideals and far too much wine — when Combeferre had been able to put into action his previously half-formed plans. Though plans was perhaps an incorrect term, as Combeferre hadn’t planned on this happening, had only opined how he wished things would turn out to bring the most happiness to their friends — or rather, the most happiness to Grantaire.

Combeferre had long realized that he harbored feelings toward Grantaire, feelings that Grantaire instead had towards Enjolras. He could not have pinpointed exactly why he had such affections for Grantaire — in as much as Grantaire was Enjolras’s true opposite, he was as much Combeferre’s, at least in certain senses — but perhaps that was the draw. Grantaire was kind, when he wished to be and often at the most unsuspecting moments, and well-spoken, at least when the alcohol did not send him on rambling soliloquies; funny, when his humor did not run into the vulgar, and intelligent, that much was clear from any conversation Combeferre had engaged in with him; he was not unattractive, swarthy and well-muscled, and if his body and face showed what hardships he had encountered in life, Combeferre did not find that aesthetically unappealing.

But whatever the cause of his affections, he had long since abandoned any true hope of Grantaire reciprocating his feelings, not when the dark-haired man felt so strongly towards Enjolras. But if he could not have his feelings with Grantaire reciprocated, he could work towards getting Enjolras to reciprocate Grantaire’s feelings, could he not?

At least, that is what he told himself, and when the opportunity presented itself, logic told Combeferre to seize the moment.

It did not present itself in the most auspicious way — Combeferre had stepped outside of the Musain one evening following a meeting to find Grantaire doubled over, holding himself up with one hand against the wall of the Musain, emptying the contents of his stomach. “Grantaire?” Combeferre had called.

Grantaire looked up and shakily wiped his mouth with the back of his hand. “Ah, Combeferre,” he said, forcing a smile onto his face. “My apologies that you must see me this way. The wine has not been kind on my stomach this eve.”

Combeferre frowned at him. “I did not think you had drunk nearly enough to need to purge yourself this early on.”

“Evidently you have not been paying close enough attention to my drinking,” Grantaire replied, clearly aiming for levity, though his smile was more of a grimace. “It is nothing important. A mere misestimation of my limits. It will not happen again.”

Combeferre’s frown deepened. “It may not be my place to say anything—” he started, and Grantaire snorted and waved a dismissive hand.

“I promise, if your place is overstepped, I’ll not tell Enjolras to spare you from the lecture about personal autonomy.”

Though Combeferre half-smiled at that comment, his expression quickly became serious again. “You say that it will not happen again, just as you say that it is unimportant, but I believe it to be of utmost importance. Your health is important.” He did not say ‘to me’, though the words seemed implied.

Grantaire slowly straightened, his own expression oddly blank. “My health is important?” he repeated. “To whom is my health important? Surely not I, for I bartered my health away in favor of absinthe and frivolity years ago. My health has no impact on the Cause for which you fight, though admittedly my sobriety could provide less of a distraction than my drunkness.”

“And your sobriety could perhaps provide a better or at least different sort of distraction to Enjolras.”

Now Grantaire cocked his head slightly, his brow furrowed. “If I am a distraction of any sort, he hides it well. Certainly I have been the subject of his ire on more than one occasion, but as a nonbeliever in a den of credence, that is only to be expected.”

Combeferre could not help but flush slightly, but carried on determinedly. “And yet you would seek to be more than that to Enjolras, would you not?”

Grantaire’s lips tightened, and for a moment Combeferre thought that he might call an end to the conversation. Instead, Grantaire said stiffly, “And if I did? What, you think my sobriety would have an impact on that? Surely it would be easier to convert me to a zealot than implore me to give up my drink, and would perhaps have a similar impact upon our noble leader.”

For a moment, Combeferre was lost for a reply, not as ready as Grantaire with a barbed comeback for every argument. But unlike Enjolras and Grantaire, whose verbal spars were often off-the-cuff, quick responses driven more by heat than by actual conviction, Combeferre’s arguments were measured, calm, logical, and he would not change that now. Instead, he looked carefully at Grantaire, weighing his options. “It would perhaps be easier to convert you to the Cause,” he acknowledged slowly. “But I believe the more lasting impact would be to wean you from your drink, both for yourself, and for the Cause.”

Though Grantaire did not look convinced, he changed tack, his eyes narrowing slightly. “This is not the first time one has attempted to sway me from the hold of alcohol. But Joly has warned me of the potential effects, and given the choice, I’ll take drunkenness and disappointing Enjolras any day.”

Combeferre inclined his head slightly. “There are dangers, of course, as your body has grown accustomed to the alcohol. But I would be willing to help you through the ill effects, for as long as you would need me.”

Grantaire looked startled. “But…why?” he managed. “Offering to assist me to be rid of the demon that haunts me alone…you are kind, Combeferre, if misguided. I know you well enough to know you would do this for reasons other than personal gain, as certainly you would gain nothing from my sobriety, but still, why? Enjolras aside, as I do not see him as motivation enough for you, why would you seek to help me?”

Combeferre shrugged. “Is it enough to say that you are my friend, and that above all else I desire to see you happy? Because if you can tell me honestly that you are happy now, as you are, with wine and absinthe your most consistent companions, I would trouble you no further.” Grantaire was silent, and Combeferre, emboldened, took a step closer to him. “But even if your sobriety had not a single impact on Enjolras, I would still encourage you to seek it, because I do believe you deserve health and happiness, Grantaire. And as your friend, I would help you find it.”

Grantaire was quiet for a long moment, staring at Combeferre with a curious look on his face. “I was not aware we were such friends.”

Combeferre half-smiled. “I would do anything for a friend who suffered in such a way. I’ve been reading some writings by an American physician, Dr. Benjamin Rush, and he believes your affliction, your dependence on alcohol, is not a moral failure, but rather a medical disease, and I must admit that I do not disagree. And if any of our companions suffered from a disease, I would seek to treat it, would I not?”

“Logic would tell you to do so,” Grantaire said evenly. “But even if this were a disease, which I do not necessarily believe, it is of my own making. And there is no cure for my own stupidity, I assure you of that.”

“But would you be willing to try?” Combeferre pressed, his gaze intent. “If it could possibly make you happy?” Grantaire’s expression did not change, and Combeferre hesitated before adding, “If it could possibly make Enjolras happy?”

Grantaire’s eyes flickered up to Combeferre’s before he looked away. “I just do not see the point in trying,” he said quietly. “Not when I would inevitably fail.”

Combeferre shook his head. “Grantaire—” he started, but Grantaire cut him off, his expression tightening.

“You would seek to dissuade me, and that is your right, just as it is mine to refuse. But I will not let you say more until you tell me why you wish to help me, truly.”

There were a multitude of reasons Combeferre could offer, including the truth, though he knew better than to utter those words at that time. So he chose instead a truth, and a plausible one at that. “Because I believe that the utmost right of every human on this Earth is to be free,” he said simply. “And that includes freedom from what ails you. And as I have the means and opportunity to assist, to help you find that freedom, I would be remiss if I did not help you.”

Grantaire hesitated before asking, “Are you sure that Enjolras did not put you up to this?”

Combeferre couldn’t help it — he laughed, though he quickly stifled it. “My friend, I am sorry. I do not mean to jest at your expense. No, of the many virtues our noble leader possesses, that is not one of them. His concern is for the masses, nameless as they are, and while he is fierce in his love of all of his companions, it is not oft on such an individual level.”

“But for you it is?” Grantaire asked, a little coolly. “For you, the Cause may be seen even in me?”

Shaking his head, Combeferre said quickly, “You are not the Cause or even a cause. You are a man struggling, and I seek only to help. You have every right to tell me to mind my own business.”

Grantaire was looking at him with an odd expression on his face. “And yet,” he said slowly, “I am finding that I do not want to.” He took a deep breath and then sighed. “I may yet regret it, but who am I to stand in the way of your noble quest for freedom? Least of all when it seems it will benefit more than just my sorry soul.”

“It will,” Combeferre had promised him. “It will.”

And though it remained too early to tell for certain if it would, during the next two weeks, Combeferre had done everything in his power to help Grantaire see that it could. The physical act of stopping the alcohol consumption did not start immediately — Combeferre insisted Grantaire see a physician or at least Joly before starting the process. Grantaire had not been wrong, nor Joly in warning him — Grantaire’s dependence on alcohol could have serious physical and psychological effects on his body with his sudden cessation, and arrangements needed to be made to help him through the worst of it. Combeferre had, true to his word, been there every step of the way through the tremors and nausea, hallucinations and convulsions. Now, Grantaire was free from the physical side effects, at least from what Combeferre had read, but had an uphill battle in facing his desire to drink again.

For that reason, Combeferre took the night and the day after to ensure his affairs were still in order — not a difficult task, as he kept a fairly tight household, his own tendency to hoard books and the odd specimen aside, but his landlady was paid through that month and next, and if he spent a little less time at his own home, she was kind enough to ensure that no one trespassed (other, apparently, than Courfeyrac, though Combeferre could not find himself surprised that his landlady had taken a shine to Courfeyrac — everyone took a shine to Courfeyrac).

But once the sun began to set the following eve, Combeferre made his way back to Grantaire’s apartment, ready to assist as needed. He found Grantaire at his table, cravat loosened, palm flat against the table where normally it would be curled around the neck of bottle. His eyes were red-rimmed and he looked tired, a product of sleeping fitfully over the past few days, but when he smiled at Combeferre, his smile was genuine. “Returned so soon?” he asked lightly. “Here I thought you might tire of my company.”

“Never,” Combeferre told him sincerely, loosening his own cravat as he sat across from him. “I promised to be here so long as you need me, and here I am.”

“And need you I do,” Grantaire said, his tone turning brisk. “I’ve procured a set of dominos — from where matters not — and need someone with which to play. Have you played before? I shall teach you if not, though I suspect you’ve a shrewd enough mind to catch on regardless.”

Combeferre smiled and shook his head, relaxing, content to spend the evening distracting Grantaire however he wished, content even more to simply spend the evening with Grantaire.

——————————

In the following weeks, such an evening became routine. Combeferre still tended to his duties, both personally and for the Cause, and both men attended Les Amis meetings with regularity. But in their free time, Combeferre and Grantaire could oft be found together, playing dominos, reading together, or just talking together. In Grantaire Combeferre found a worthy companion, more than he could have imagined when he gave thought to it before this all began. Grantaire when sober gave voice to his thoughts normally muddled by the alcohol, and Combeferre found him to have a broad intellect and warm sense of humor.

His discussions with Grantaire ranged from scientific discoveries to the most mundane, Grantaire willing to argue and balk at every turn but also consider Combeferre’s more wild notions without outright dismissing them. Combeferre used Grantaire to work through his thoughts, surprised and very pleased to find Grantaire willing to listen to anything he had to say and return his sentiments, often with arguments adjusted and calibrated perfectly.

It was everything Combeferre always thought Grantaire had the potential to be, and should have been perfect, but Combeferre could not help but feel guilty. Where he felt his friendship with Grantaire deepening, he could not help but feel that he was meant to be doing this for Enjolras’s sake, to assist Grantaire in becoming for Enjolras what he had instead become for Combeferre — a confidant, a friend, and someone on whom Combeferre could rely.

Still, he put those thoughts from his mind, because surely if Grantaire was getting better, if he was not drinking and was not tempted to drink, it did not matter for what purpose. At least, so he told himself.

But one day, following a particularly vicious argument with Enjolras as to Grantaire’s own utility, Grantaire returned to his suite of rooms sullen and silent. Combeferre trailed after him as he had been recently, but did not know what to say, Grantaire preferring to brood rather than speak. Finally, when they were both inside, Grantaire gripped the edge of the table so hard his knuckles turned white. “I desire a drink,” he said quietly. “You have heard Enjolras — even sober I bring nothing forward that he finds useful for his Cause. Grantaire is a drunk and Grantaire is useless — his words, not mine. If so he thinks, why should I not be?”

“Because you can be more than that,” Combeferre said quietly. “You are more than that. You have come so far—”

“And for what?” Grantaire challenged, his face red. “To prove to Enjolras that even sober I am no more useful to him than any gamin off the street? To show that when the time comes, none will be able to say that Grantaire did anything for the revolution?”

Combeferre shook his head. “This was never about that,” he reminded Grantaire, still quiet, though his tone was firm. “Your aim here was not in turning you into something you are not, a revolutionary zealot, but in freeing you from the chains that alcohol wrought on you.”

“But what good is freedom from chains if I’ve naught to show for it?” Grantaire asked bitterly. “Enjolras despises me just the same sober as he did drunk.”

“And this was never about Enjolras,” Combeferre told him, his volume rising slightly. “This was about freeing yourself, with the possibility of Enjolras as a hopeful side effect. Do not throw away all you have worked for these past few weeks on a wish!”

Grantaire gave Combeferre an approximation of a smile. “How strange to hear the Guide of the rebellion arguing against hope.”

Combeferre all but slammed his hand down on the table, and Grantaire flinched slightly, his eyes wide. “Desiring to have Enjolras suddenly change is not a hope, it is a delusion! I am filled with hope for you, such hope, and I want nothing more than for you to find that hope in yourself, that hope for yourself, for that is what will be your light when Enjolras cannot or will not be.”

Grantaire was silent for a long moment after that outburst, his brow drawn, his hand clenched into a fist. Finally, in a low voice that did not sound entirely like his own, he asked, “Why do you care?”

Sighing, Combeferre sat back in his seat, suddenly exhausted. “I have told you many times—” he started, his voice low, but Grantaire shook his head as well, leaning across the table until the were merely inches apart, his eyes searching Combeferre’s for the truth he saw Combeferre as hiding from him.

“Why?” Grantaire repeated, gripping Combeferre’s arms lightly. “I am not worthy of any of the time you have dedicated to this cause above the plight of the people, though this one may be just as hopeless. Why would you try so hard when you are only destined to fail, or worse? Why do you even care if I poison myself sooner rather than later? Why—”

Whatever question he was to ask next never made it out his lips, because Combeferre closed the space between them and kissed him.

For just one moment, Grantaire kissed him back, then, abruptly, pulled away. Combeferre did not quite panic, though he felt close to it. Instead, he met Grantaire’s gaze and said simply. “That is why.”

Grantaire nodded slowly, his expression troubled. “And if I did not return the sentiment?”

Combeferre shrugged. “I would have helped you anyway, will continue to help you. You are my friend, first and foremost.” He wanted to leave it there, but could not stop himself from asking, “Do you not return the sentiment, then?”

Grantaire shrugged and sat back in his chair. “In truth, I know not how I feel,” he said slowly. “Between the alcohol and Enjolras…” He shook his head as if unwilling to finish the thought. “Will you give me time to work out what I feel?”

“Of course,” Combeferre responded instantly. “What is most important to me, what I want above all, is for you to get better for yourself, whatever that takes.”

——————————

Though true to his word Combeferre still assisted Grantaire over the next several days, something had shifted in their friendship, something that could not shift back until Grantaire made a decision, and it made Combeferre uneasy, knowing his fate rested in so tenuous a position. This feeling was not helped by Enjolras sitting next to him after a Les Amis meeting one night the next week, after most of their friends had adjourned for different company and far better wine. “Courfeyrac says that you have been spending a lot of time with Grantaire lately,” Enjolras said in lieu of preamble, his expression unreadable as he looked at Combeferre.

Combeferre shrugged. “He and I have discovered mutual interests. Despite your frequent frustration with him, I find his company enjoyable.” He paused before asking, “Is this a problem? For the Cause? Or…for a different reason?”

Enjolras looked surprised at the question, though his expression quickly smoothed out. “Not a problem,” he hedged. “Certainly not for the Cause, as what a man does in his private life should have no impact on our fight unless, of course, it directly counters the fight for all.” He fell silent, his brow furrowing as if in thought before saying hesitantly, “I did not know you felt that way. The…Greek way.”

Half-smiling at Enjolras’s awkward phrasing, Combeferre shrugged. “There are many among our number who indulge in Greek love, some exclusively. I admit that I would not define myself strictly in the Greek fashion.”

Enjolras nodded slowly. “And you…and Grantaire…”

Combeferre’s smile faded. “If a man’s private life has no impact on the Cause, for what purpose do you ask me this?”

To Combeferre’s surprise, Enjolras flushed. “I merely sought to know what you were doing,” he muttered.

Combeferre shook his head, suddenly angry, angry at the entire situation. “Why would it matter what I am doing?” he asked loudly. “For surely you don’t care for Grantaire — you have made that abundantly clear. You openly despise the man, or at least act as if you do, and yet the moment someone else shows interest, you…” He bit off his words and allowed himself to calm slightly before saying in a low voice, “I do not even know what you mean to accomplish here, except to say that toying with our comrade’s emotions is a low move designed for far less worthy men.” Enjolras’s jaw clenched but he did not answer, and Combeferre said, still quiet, “If you do not have feelings for him, at least tell the man as such, let him down from whatever fantasies he lives in his head.”

“The problem is not that I do not have feelings for him,” Enjolras said quietly, avoiding Combeferre’s gaze. “The problem is that I do.”

Combeferre stared at him, his heart beating almost a painful rhythm in his chest. This was everything he had feared, everything even he, undoubtedly Enjolras’s closest friend, could not have anticipated. Certainly he had known Enjolras’s feelings toward Grantaire were more complex than mere disdain, but to know that Enjolras harbored feelings of this nature… “Then you must tell him,” Combeferre croaked, his mouth dry.

Enjolras just shook his head. “I cannot.” He managed a small smile. “And now you see why it is a problem.”

Frowning, Combeferre said slowly, “I am afraid that I do not.”

Enjolras sighed, something in his expression turning stony. “I cannot act on these feelings for fear of what I would bring on Grantaire by doing so. Our Cause, the sedition we utter so freely in this room, it will have consequences, ramifications, and while I would sacrifice myself and my life and my dignity, while I would gladly accept any man doing the same for our Cause, I would not see Grantaire dragged into that, not when his belief lies not with our Cause.”

Combeferre’s brow furrowed. “But Grantaire should be allowed that choice, just as any of our number would be granted that choice when the time comes.”

Tilting his head slightly, Enjolras said quietly, “It seems to me that Grantaire has made his choice, and in my estimation, he has chosen well.” Combeferre shook his head, but the words he would utter in protest died in his throat as Enjolras continued, his voice uncharacteristically gentle, “My friend, you are in many ways the sum of the best parts of myself, and all that I could never be. If it cannot be me, there is no other that I would wish for Grantaire.”

“But he wants you,” Combeferre replied, a little desperately, even if this was not the argument he truly wanted to make; on occasion, appealing to Enjolras’s passions, even his now confessed humanly passions, was the best way to get through to him.

Here, however, even that seemed destined to fail, as Enjolras met his gaze steadily. “And he needs you.” Abruptly, Enjolras stood, though he paused and tentatively reached out to grip Combeferre’s shoulder. “As always, I leave what I cannot trust myself with in the capable hands of my closest lieutenant.”

In that moment, any further argument Combeferre might have made faltered, and he could no no more than look up at Enjolras and nod slowly, even if his chest seemed locked in the vice-like grip of guilt. He needed to tell Grantaire what Enjolras felt for him — it was only right to do so, was it not? Combeferre would never seek to purposefully leave any, least of all one of his own comrades, in willful ignorance. Enjolras may not wish Grantaire to know, but Combeferre could not keep this from him.

Could he?

It would be better for him, certainly, if Grantaire never discovered the conversation that had transpired between Enjolras and himself — he already knew his affections could never be truly reciprocated, at best a pale imitation of what Grantaire felt towards Enjolras, and any glimmer of hope would cause even that pale imitation to fade completely. But would it not be better for Grantaire to know the truth?

The thought haunted him on his entire walk back to his apartment, and with it the debate over whether to tell Grantaire or to not. But when he arrived at his apartment, the thought was put from his mind by the form of the man in question leaning against the wall next to his door. “Grantaire?” Combeferre asked, surprised.

Grantaire looked up at him and smiled, a genuine smile, such as Combeferre had not seen from Grantaire since, it seemed, this entire thing had begun. “I hope you do not mind the intrusion.”

“Indeed not,” Combeferre said, opening his door and ushering Grantaire inside. “Though if you are going to make a habit of stopping by, I recommend becoming acquainted with my landlady; she appears to have no regard for thoughts of privacy.”

Grantaire’s smile widened. “I may or may not have spoken with her before you arrived,” he admitted. “She offered me admittance, but I thought it best to wait for you.”

Combeferre harrumphed and shook his head. “Yes, perhaps for the best,” he said, glancing around to ensure his suite was not overly messy, cluttered as it was with his many books, specimens, and other belongings. “Please, make yourself comfortable.”

Grantaire, however, did not sit, instead shifting awkwardly. “I had rather hoped we could talk.”

Combeferre shot him a sideways glance. “Yes, I think that would be for the best,” he said softly.

Though Grantaire nodded, there was something of a nervous energy to the movement, and though he started, “I wanted to come to tell you…”, he quickly trailed off, instead darting forward to kiss Combeferre square on the lips.

Freezing, Combeferre’s eyes opened wide in shock, and he would have pulled back were it not for Grantaire pulling away as quickly as he had moved forward, his eyes wide as well. “What…what was that?” Combeferre managed.

“When I returned to my room this eve, I longed for a drink,” Grantaire told him, still with the same nervous energy, glancing at Combeferre and away. “I longed for a drink and for the oblivion it would provide, but then I thought instead of you.”

Combeferre stared at him. “Of me,” he repeated quietly.

Grantaire nodded, still not looking at him. “I thought of you, and all that you’ve done for me, and how far I have journeyed over these past several weeks. And suddenly I…” He glanced at Combeferre again, almost shyly. “I found I did not want to drink so badly.”

Combeferre reached forward to grab both of Grantaire’s hands with his own. “Grantaire, that is wonderful to hear,” he said, sincerely. “But do not overplay my role in this. Your journey has been of your own making, and you are the one to sustain its longevity.”

“Whether true or not, I did not just think of you in that sense,” Grantaire said in a low voice. “I asked for time, to work out how I feel, and I still lack a sufficient answer. But I realized I may never have a satisfactory response. And yet my feet carried me to your door as if it was the most natural thing in the world, and I think that to be an answer in and of itself.”

Combeferre’s brow furrowed slightly. “What are you saying?”

“I am saying,” Grantaire started, then shook his head. “I am saying nothing. I am doingthis.”

He pulled Combeferre to him and kissed him soundly. Combeferre could not help but return this kiss, wrapping his arms around Grantaire and giving in to what he had so longed for and what he had never dared to hope would come to pass.

As Grantaire had said, perhaps this was an answer in and of itself to whether Combeferre should tell Grantaire. Or at least so he told himself as he pushed the guilt aside and tightened his grip on Grantaire.

——————————

The next morning, the guilt had returned in full force, and Combeferre decided to call on Courfeyrac, who had been there for the beginning of this whole debacle and might have some form of advice to offer, beyond what gnawed at the back of Combeferre’s mind.

“Combeferre!” Courfeyrac said when he answered his door, sounding surprised. “What brings you here on a day such as this? I would have expected you to attend to Grantaire’s to continue assisting him.”

Combeferre shrugged, and Courfeyrac’s smile faltered slightly. “Something has happened,” he said, opening the door wider so that Combeferre could follow him inside. “Involving Grantaire, naturally. Did he rebuff your advances?”

“Quite the opposite, actually,” Combeferre said, sitting down at Courfeyrac’s table and running a tired hand across his face.

Courfeyrac sat as well, slowly smiling. “So you have come to share the good news? My friend, I am glad for you, and for Grantaire! It is not necessarily a match I would have foreseen, but if you are happy…” He trailed off, looking closely at Combeferre. “And yet you are not happy, which leads me to believe there is more to the story.”

Combeferre fixed his gaze on the wall behind Courfeyrac as he said emotionlessly, “I am not the only one harboring affections towards Grantaire. Enjolras is, as well, only he made it clear to me that he has no intention of acting on those affections, that for him the Cause will always be most important.”

“Ah.” Courfeyrac sat back in his seat, tapping his chin thoughtfully. “And I shall assume that Grantaire knows nothing of our Noble Leader’s returned affections?”

Shaking his head, Combeferre said softly, “Enjolras does not wish him to know.”

Courfeyrac frowned. “Has he asked that you not court Grantaire?”

Combeferre sighed and shook his head again. “Quite the opposite. He has given his blessing.”

Now Courfeyrac’s frown deepened. “Then, forgive me, I do not see the problem.”

“It is dishonest, is it not?” Combeferre asked, meeting Courfeyrac’s eyes for the first time. “To withhold such information from Grantaire when he would hunger for this most of all? How can I go about courting him, or even just assisting him with his alcohol problems when I bear a secret such as this one?”

“By knowing that the truth does no one any good,” Courfeyrac told him, sounding almost surprised, as if the answer was apparent.

Frowning, Combeferre returned, “By my estimation, the truth would do Grantaire plenty of good, and perhaps more good than anything he and I could share..”

Courfeyrac leaned forward slightly in his chair. “But it is not your secret to tell, and dismissing the potential between you two off hand because of this would be folly.” Combeferre’s jaw had a stubborn set to it, and Courfeyrac sighed before saying quietly, “Let me rephrase — will the truth change anything? Will it help Grantaire, truly? Or will it only hurt, knowing that Enjolras returns his affections but refuses to act on them?”

Combeferre shook his head. “It matters not. He should be free to choose.”

“Just as Enjolras is free to deny his feelings,” Courfeyrac said evenly. “Grantaire is still free to choose Enjolras — you are not denying him that choice, only withholding a certain incentive for one choice over another.”

“Then it is not an informed choice,” Combeferre insisted. “Education is the only way to ensure that the choice made is fully understood and that the chooser fully consents.”

“And again, what would it change for him to be fully informed?” Courfeyrac challenged. “As it stands, his current choice is between certainty — your feelings for him — and uncertainty — the potential for Enjolras to return his feelings, or not. Even if he knew Enjolras returned his feelings, the choice is still between certainty and the uncertainty of the possibility that Enjolras may or may not choose to act on those feelings.”

Combeferre shook his head again, a million arguments springing to mind despite the fact that he wanted to believe Courfeyrac, who did not give him a chance to voice any of those arguments. “If you tell him, you will only hurt him, yourself, and Enjolras. If you do not tell him, all three of you have a chance at happiness.”

“But the freedom that truth provides above all—” Combeferre protested weakly.

Courfeyrac half-smiled and reached out to cup Combeferre’s cheek, something gentle and a little hesitant in his touch. “Some secrets were meant to be kept, mon ami,” he whispered.

For the second time in as many days, Combeferre found himself unable to reply, not because he could not find the argument — indeed, he saw numerous arguments to that, just as he always did — but because he could not find it in himself to do so. “What am I to do then?”

Shrugging, Courfeyrac leaned back in his chair. “Off-hand? I’d suggest finding Grantaire, spending time with him. You’ve gotten what you wished for, or perhaps did not dare to hope for — perhaps you should try enjoying it.”

Could Combeferre do that? Could he put aside the guilt and the analysis of morality in this situation and simply enjoy the fact that, however uninformed his choice may have been, Grantaire had, for the moment, chosen him?

He did not know, but surely it would not hurt things further to at least try.

So he stood, bid Courfeyrac farewell, and went to Grantaire’s apartment. “Combeferre!” Grantaire said when he opened his door. “I…I did not know if I would see you today.”

Combeferre smiled warmly at him. “I was out this way and thought I would stop in to see how you were doing this morning.”

Grantaire smirked. “Coming to see if I regret our conversation last night?” Combeferre looked at him, startled, and Grantaire’s smile softened. “I do not, if that was what you were wondering. And if it is not what you were wondering, you are assured now in any case.”

Rolling his eyes, Combeferre cleared his throat and said, “I had thought to ask you to accompany me on a stroll. To the jardin, perhaps? It is a lovely day outside, the month being as it is, and I thought your company might be a nice addition.”

“How formal,” Grantaire teased. “Shall I start using vous instead of tu?”

Combeferre leaned in and kissed Grantaire, a swift kiss, conscious of the fact that they stood in Grantaire’s hallway still, where any could see them, and while the laws against sodomy had been long overturned, the stigma remained. “Is that less formal for you?” he asked, a little breathlessly.

Grantaire smiled up at him. “I do believe it is.” He grabbed his jacket and buttoned it over his waistcoat, and took Combeferre’s arm, allowing him to lead him down to the street. “And what shall we talk about on this fine walk?”

“Whatever you wish to discuss,” Combeferre said easily.

Grantaire glanced over at him. “After all this time, how have you not yet grown bored of my rambling?”

“I find your rambling interesting,” Combeferre told him truthfully. “And besides, you allow me the occasional enthusiastic long-winded rant on whatever subject has captured my attention recently.”

Grantaire nodded sagely. “Ah, yes, I do believe that I shall never forget your disquisition on, what was it, the carotid artery?” Combeferre snorted and shook his head, and Grantaire smiled at him. “What a fine pair we make, then, myself with my rambling, you with your enthusiastic discussions of the mundane.”

Combeferre looked at Grantaire fondly. “Indeed,” he said quietly, in far more serious a tone than Grantaire had used. “What a fine pair we make.”

——————————

Over the next few weeks, they grew closer still. Where before Combeferre had frequented Grantaire’s apartment to assist him however he might need it while learning to live without alcohol, now both often found themselves at the other’s apartment, or else staying at the Musain long after everyone else had long since returned to their beds. Combeferre blearily opened his door early one morning for Grantaire to rush in because he had spent a sleepless night contemplating one of Combeferre’s arguments and had discovered its weakness, just as Grantaire answered his door late at night, already dressed in his bedclothes, to be pulled from his apartment to go with Combeferre to view what Combeferre called an astronomical phenomenon.

Grantaire showed Combeferre the best places in Paris, including a decrepit booksellers, where he lost Combeferre inside for the better part of an afternoon. For his part, Combeferre showed Grantaire the meaning of wonder, of discovery, whether found in one of Combeferre’s scientific specimens or in the pages of a book that Grantaire had not yet read. They whiled away the hours not dedicated to the Cause or their other interests together.

Their relationship was more intellectual than anything, especially physical — though they touched, and often, hands brushing against each other, fingers linking, occasional companionable cuddling on Combeferre’s méridienne, even lingering kisses pressed to forehead or temples, only a few times did they truly kiss again, and always initiated by Grantaire. Combeferre did not wish to force him to do anything he did not want to do, and both men were content with the way their relationship progressed. It may not be traditional courtship, but it was hardly a traditional arrangement in the first place.

And they fought — how could they not? As much as Grantaire was Enjolras’s true opposite, he must also be in many ways Combeferre’s, especially regarding the the potential for progress on its own. But where Enjolras and Grantaire’s arguments had often been bitter and caustic, Combeferre and Grantaire’s arguments were more controlled and careful. They were not seeking to prove the other wrong but rather test the other’s tenets, and this led to all manners of discussions.

One such discussion, however, shook Combeferre’s convictions. One evening following a meeting at the Musain in early May, Grantaire asked, “Where does our Noble Leader adjourn to so early in the evening? Does he not have grand plans to devise?”

“The time for planning is almost past,” Courfeyrac told Grantaire as he passed by. “And Enjolras goes to discuss armaments with others.”

Grantaire arched an eyebrow at Combeferre, who shrugged and looked away. Shaking his head slightly, Grantaire took a sip of the water that had taken the place of wine in his cup. “Well, if it is for the greater good,” he muttered, smirking slightly.

Combeferre, however, frowned, and looked back at him. “The greater good?” he questioned. “To hear those words from your mouth when you believe in none of this — I am surprised, to say the least.”

Grantaire shrugged and leaned back in his chair, reaching up to loosen his cravat, sensing an argument in the making. “It is not the ends that I have difficulty in believing, though I do not see them coming to fruition in our lifetime. Certainly a free and prosperous world is as great a fantasy to entertain as any. But the means to getting there — well, I doubt the people shall rise in force now any more than they have these past three decades, but that does not imply the means are not justified by said fantasy.”

Shaking his head, Combeferre leaned forward. “I would not see the means take place if I had any ability to stop them. Education could just as easily achieve our ends, over a more advanced timeline. And yes, yes, I recognize the suffering happening now and the necessity of our actions to alleviate said suffering now, but in my heart I long for a different strategy.” He shook his head again and sat back in his seat. “It seems we offer society only two choices: conflagration or darkness, without acknowledging a third alternative, and that, to me, seems deceitful, if not an outright lie that we perpetrate in hopes of bringing the populace to our revolution.”

Grantaire laughed. “And what is a little deceit in society, when the end results are so longed for? Surely lies are a small price to pay for so sweet a reward.”

Abruptly, Combeferre stood, his face ashen. “Lies are not an easy price for any man to pay, small though they may be,” he said in a low voice. “And the reward not always sweet enough to quell the guilt a man may feel.”

Without another word he grabbed his hat and left, striding away into the night, leaving Grantaire staring after him, bewildered. “What is it you said, capital R?” Bossuet called from across the room, and Grantaire just shook his head.

“I honestly do not know.”

Combeferre strode back to his apartment, battling the sudden guilt that he had managed to keep tamped down over the preceding weeks. For the greater good, he thought bitterly. Was that not exactly what had started this whole mess? Courfeyrac and Enjolras seemed not to mind deceiving Grantaire, as it was for some greater good. Certainly they couched it in terms of happiness, but could true happiness be achieved when one was not even free to learn the truth?

And worse, he had willingly gone along with it, had squashed his own misgivings, believing that what he felt for Grantaire was more important than anything else, more important certainly than the potential pain Grantaire might feel knowing Enjolras shared his affections and still rejected him, the ends, Grantaire’s happiness, his own happiness, justifying his lie. And now, to hear such an argument parroted glibly back at him by Grantaire…

It was too much to bear.

By the time he had arrived back at his building, his pace had slowed, as had his breathing and the pounding of his heart, and indeed, he felt a little foolish, for his storming out if not for the sentiment that inspired him to do so. Perhaps, though, this would lead to the conversation he should have had many weeks ago now; perhaps it was time to end this charade once and for all.

He was not entirely surprised when not even twenty minutes later a tentative knock sounded on his door, and was even less surprised when it was Grantaire who entered, looking a little nervous. “I came to apologize,” he said, without preamble. “I know not what offense I gave, but I assure you, it was accidental.”

Combeferre shook his head. “The apology is mine to make,” he said quietly. “My reaction was unjustified. I—”

He broke off, debating now that Grantaire was in front of him how much he should say, if anything. “Combeferre?” Grantaire said quietly, his tone soft and gentle and far more than Combeferre deserved.

“It is nothing,” Combeferre said stiffly, turning away from Grantaire as he added, “I do sometimes wonder whether I have done the right thing.”

Grantaire reached out and touched his shoulder tentatively. “I do not believe in much,” he told Combeferre quietly. “But I do not believe that you have done wrong by your country or your fellow man, and I believe you an honorable man with honorable intentions, and those intentions may yet be rewarded by the rise of the people.”

Combeferre closed his eyes, for of course Grantaire thought he referred to the revolution, to the Cause — how could Grantaire even think that Combeferre referred to him, to them? “Of course,” Combeferre said, turning to Grantaire and taking both his hands in his. “You are absolutely right. I overreacted.”

Grantaire smiled up at him. “You did get very serious on me for a moment.” He reached up and cupped Combeferre’s cheek, and Combeferre could not help but lean into the touch. “I know how seriously you take the education of our countrymen, of all people, but do not forget to enjoy what little moments of peace we have together.”

Combeferre lifted his own hand to rest it on top of Grantaire’s. “I could never,” he told him softly. “I treasure these moments most of all.”

“Good,” Grantaire said, suddenly brisk, his eyes sparkling with merriment. “For I believe you said earlier this evening that you found another error in the Dictionary of the Academy, and I know nothing brings you joy like discussing such faulty texts.”

Laughing, Combeferre let Grantaire pull him in the direction of the settee, his guilt, neither assuaged nor forgotten, again tamped down in Grantaire’s presence.

But then June dawned, and with it, the statement, “General Lamarque is dead”, which changed everything.

They were all gathered at the Musain, and the room went silent at the announcement, all eyes on Enjolras, who seemed almost frozen for a moment, profiled against the fire, his head bowed. “Comrades,” he said slowly. “If ever we have been awaiting a sign to rally the people, this is it. General Lamarque, a man who spoke for the people, now lies dead, his voice silenced, but we will not be silenced in his stead.” Indeed, Enjolras’s voice grew steadily as he looked around the room. “His death brings forward a moment of clarity, a moment of necessity, and a moment of opportunity. The grief our comrades feel will not be in vain, for we shall channel that grief into anger, and anger into action. His funeral day must be the day our barricades arise!”

“Hear, hear!” someone shouted, and Enjolras nodded officiously.

“We will fight for our fellow countrymen, stand for our fellow countrymen, even die for our fellow countrymen, if the need arises! The blood of the martyrs will paint the streets with the color of our Cause! Who will stand with me, who will fight with me, who will die with me?”

The entire room burst into enthusiastic cheers, save for two: Combeferre and Grantaire. Combeferre and Grantaire’s eyes met across the room, Combeferre as concerned for Grantaire’s reaction to this news as to anything. Grantaire just smiled, a twisted, horrible approximation of his usual, cheerful grin, and leaned forward to pluck Bossuet’s bottle of wine off of the table, raising it in a mock salute before lifting it to his lips, Combeferre’s heart breaking in the process.

——————————-

The next few days passed in a blur of preparations, final touches put on the plans established months ago, waiting only for the proper time to be enacted, and Combeferre was too busy to dwell on Grantaire, on Grantaire’s return to drinking, and what this meant for them. Did it matter much what it meant for them if Combeferre could find himself shot down by a National Guardsman in the coming days?

Still, he could not put the thought from his mind, not when he looked for Grantaire at every turn only to not find him. Finally, when he had a free moment, he went to Grantaire’s apartment, but did not find him there. Instead, he found him at the Musain, laughing and joking with Joly and Bossuet as if nothing was wrong, save for the bottle prominent at his right hand. “Combeferre!” Joly called, beckoning to him. “Join us, if you are not too busy with your preparations!”

Grantaire looked up when Joly spoke, and his smile faded. Combeferre could see what the others either could or would not, the dark circles around Grantaire’s eyes and the unhealthy pallor of his skin. Clearly Grantaire had not taken well to drinking again. Combeferre cleared his throat, his eyes not leaving Grantaire’s. “I am afraid I have not the time for merriment at this hour. I merely wondered if I could speak with Grantaire for a moment.”

Joly and Bossuet exchanged glances, and Grantaire stood, a little unsteadily. “Has Enjolras sent you to scold me for my lack of involvement?” he asked lightly, knowing full well that was not why Combeferre was there. “He would have better luck coming himself if he wished to convince me.”

Both Joly and Bossuet laughed, and Grantaire allowed Combeferre to lead him to a quiet corner of the café. “You know very well why I am here,” Combeferre said, quietly. “I come to ask you not to give up everything you have worked so hard for over these past few weeks. What will happen will happen, but you do not need to return to alcohol.”

“Enjolras indeed would have had better luck with this mission,” Grantaire replied coolly. “I drink to forget life, and to forget that life is about to end.”

Combeferre shook his head. “Grantaire—” he asked, reaching out for Grantaire, who jerked his arm out of Combeferre’s reach.

“Do not patronize me,” Grantaire said in a low voice. “None of it matters now, do you not see that? Enjolras will die. This is no mere theoretical revolution now, to be discussed in back rooms among the fumes of wine and haze of smoke. This is war coming, or do you think the National Guard will merely allow the barricades to rise without bringing out their own cannons and artillery?” He shook his head, his face flushed, and spat, “Enjolras will die. And if he does, there is no point in any of this.”

Combeferre recoiled as if Grantaire had struck him, his expression tightening. “Then I see my efforts have been in vain,” he said, stiffly. “I bid you good day.”

He turned on heel and left, making it outside before the tears that pricked at the corners of his eyes could fall, and by the time he had returned to Enjolras’s, the tears had been replaced by anger and by a hollow feeling in his chest.

He had known that Grantaire did not fully return his feelings, but now, the truth was as plain as day — Grantaire did not love him. Grantaire had never loved him. How could he, when Combeferre was no Enjolras? And everything that Combeferre had tried to do, to accomplish, had been worthless.

Luckily, Combeferre was never one for brooding, and turned his attention back to the task at hand and the preparations underway, leaving the hurt and anger and heartbreaking pain that rose in his chest to be dealt with another day.

——————————

But the prospect of another day, of course, became limited, and when the barricades rose, Combeferre rose with them, shouting and cheering with the rest. And when reality set in, when they all were finally situated at the Corinthe, only then did Combeferre turn his attention from the gun in his hand and two in his belt back to Grantaire, watching from the sidelines as Grantaire drank himself to near oblivion before all but begging Enjolras to let him stay at the barricade.

It was everything Combeferre had not wanted for Grantaire. Every ill advised decision Combeferre had made, every lie he had told, it had been in the hopes that Grantaire would not be a part of this, here at the end of all things. But as with all of Combeferre’s plans, it seemed a dashed hope now.

Still, just as Combeferre was not willing to give up on his hopes for the future, he was not willing to give up on Grantaire, even now, and so late that night, when the fighting had ceased and everyone sensible had turned to sleeping, he crept back inside the Corinthe, shaking Grantaire to wake him and sitting beside him at the table. Grantaire blinked blearily at him. “Combeferre,” he said slowly, his voice soft and sad, and not as drunk as Combeferre might have expected. “Why have you come?”

“To plead with you, one final time: leave this place. The barricade is no place for you. It is a place of lofty ideals and the hopes of a world that you have never believed in, and it will be painted with the blood of those who believe. But you have never believed, and I would not see your blood needlessly shed.” He hastened to add, when he saw the look on Grantaire’s face, “I would not forbid your presence here, nor would I ever tell you that you disgrace what we do here, because I do not believe that, nor have I ever. But I would wish you to see you live, you most of all.”

Grantaire managed a small smile, though it did not meet his eyes, and shook his head slowly. “I cannot leave,” he told Combeferre quietly. “While still Enjolras draws breath, here I must remain, pathetic though that may seem.”

Combeferre inclined his head, his heart pounding in his ears. A not small part of him considered telling Grantaire that Enjolras loved him — here, in this place, what was there to lose by telling? What was there to be gained by keeping this secret for one moment longer?

But looking into Grantaire’s eyes, Combeferre found he could not, even here. There was a chance, however small, that Grantaire might live through this instead of dying with Enjolras or dying for Enjolras, and no matter how slim the chance, it was a chance that Combeferre was willing to take. Instead, he cleared his throat and told him, sincerely, “For my sake, then — because I love you.”

It was the first time that he had uttered those words to Grantaire, and Grantaire did not look surprised to hear them, though he seemed pained for a moment. “And how I wish it was enough, for both our sakes,” Grantaire whispered.

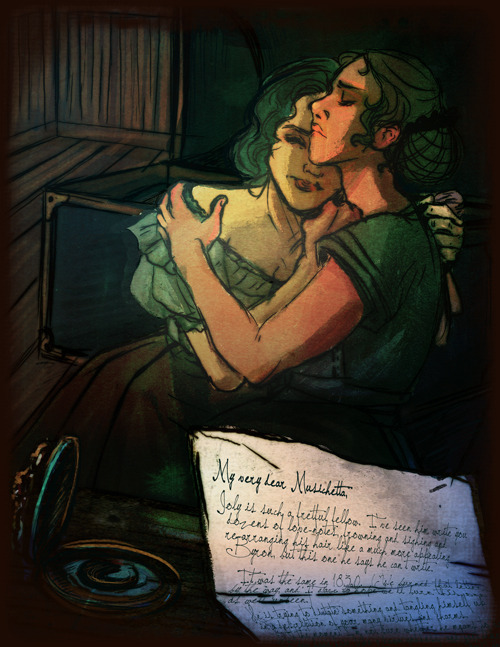

Combeferre nodded, slowly, for he wished it, too, in the depths of his heart. Grantaire reached out for him and Combeferre went readily to his embrace, allowing Grantaire to kiss him, assumedly for the last time, his hands balling in Grantaire’s waistcoat, as if by holding him tightly enough this might all be a nightmare from which they could both wake.

Instead, they both pulled reluctantly away, though Grantaire tangled his fingers with Combeferre’s. “You must make me a promise,” he said in a low voice. “If somehow you survive this, you must promise to take care of yourself. You will meet someone else, you will fall in love, and I want that for you, and I want you to want that for yourself. I want you to live, Combeferre, I want every dream you have shared with me to come true.”

“I want the same thing for you,” Combeferre said, his voice breaking. He took a deep breath and nodded. “I promise.” He squeezed Grantaire’s hand. “And will you promise the same, mon ami? Should you survive the barricade, will you live life as it is meant to be lived? Will you again give up alcohol and become the man with whom I fell in love?”

Grantaire shrugged and looked away, his grip on Combeferre’s hand loosening. “I do not know what life would hold for me outside of this barricade,” he said softly. “And I know not if I will have a chance to find out.” He managed a small smile and squeezed Combeferre’s hand. “Now I must return to my slumber, before the wine loosens my tongue even further, and you must return to the barricade before you are missed.”

Combeferre stood before asking, a little desperately, “There was never a choice for you, was there?”

Now Grantaire smiled slightly. “Ah, my friend, even now you worry about the freedom of choice. There was always a choice — there always is. But my choice was made long ago, and I cannot change course now.”

Combeferre nodded and bent to kiss Grantaire’s forehead. “No more than I can change course,” he said in a quiet voice. “Sleep well, Grantaire.”

“And you,” Grantaire replied gently. “When sleep should take you.”

Combeferre slipped back outside, at once overwhelmed by emotion and yet somehow finding his burdens had been lifted. He had done what he could, none could argue otherwise now, and even if the result was not what he wished, even if still he withheld from Grantaire what he should have told him many weeks past, he still went to what fitful sleep the barricade could provide feeling less guilty than he had in weeks.

And the next day, when, bending to lift a wounded soldier on the barricade, Combeferre was transfixed by three blows from a bayonet, he managed to look up at the sky for one last time, his last thought the hope he still had that Grantaire, one way or another, might find it in himself to be free.