#placental

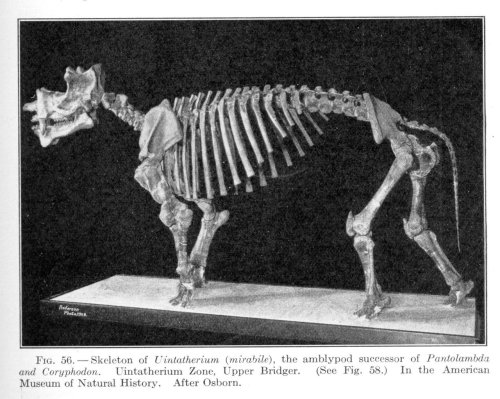

Uintatherium

Mounted specimen from American Museum of Natural History, and currently part of the traveling Extreme Mammals exhibit.

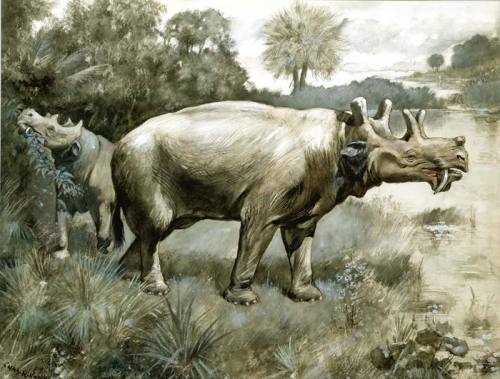

Reconstruction by Charles Knight

When: Eocene (~49 to 39 million years ago)

Where: North America

What:Uintatherium is one of the first large mammalian herbivores. It stood about 6 feet (~1.8 meters) high at the shoulder and was roughly 13 feet (~4 meters) long. This isn't that large for an animal today, but in the Eocene it was a giant! It lived in the lush sub-tropical forests of mid-Eocene North America, most likely eating a combination of terrestrial bushes and shrubs along with aquatic plants from lakes and marshes. Uintatherium has a nasty pair of upper canines, not what you would expect from a herbivore! It is thought that these teeth were involved in sexual display, as they appear to be much larger in males than females. Uintatherium vanishes from the fossil record in the late Eocene, at about the time the temperature of North America was falling and the vegetation was thinning out.

Uintatherium was also one of the fossils involved in the great ‘Bone Wars’ between Cope and Marsh. It was by far the largest of the fossils to come out of the Fort Bridger fossil localities in Wyoming (this fort gives its name to a land mammal age - The Bridgerian!), and thus highly prized. Cope and Marsh both applied multiple names to specimens from this region which would later prove to all belong to the same species. The name Uintatherium wasn’t even one applied by Cope OR Marsh. Joseph Leidy named this creature in 1872, just barely edging out Marsh’s names of Dinoceras and Tinoceras. So that particular battle in the bone wars was won by someone who didn’t even have much of an interesting in fighting!

Uintatherium is not thought to have any living descendants, it is possible that the Eocene Uintatherium was the last of its kin. However, the position of Uintatherium and its brethren (grouped as the Dinocerata) within the mammal family tree is highly uncertain. They are well accepted as placental mammals, but beyond that? It is highly debated, and in my opinion, nobody has really done a rigorous enough study to support any one position over another.

Post link

Palaeolagus

When: Late Eocene to Mid Oligocene (~38 to 27 million years ago)

Where: North America

What:Palaeolagus is a fossil lagomorph. Lagomorpha is an order of mammals, that contains rabbits, hares, and pikas. Within the bunny-order rabbits and hares are more closely related to either other than either is to the pikas. If you are not familiar with pikas go check out some pictures! They are really cute little guys that resemble guinea pigs more than they do rabbits, but they are most assuredly lagomorphs. Palaeolagus falls outside all living lagomorphs in their evolutionary lineage. It can be thought of as representative of the common ancestor of all living lagomorphs.

Palaeolagus lived in North America in the late Eocene, after the dense forests had left and the grasslands of the plains started to expand. This 10 inch (~25 cm) long herbivore spread throughout the continent during the Oligocene as the grasslands grew. Palaeolagus could not hop, its hind legs show none of the features that make a hopping locomotion style possible in living rabbits.This ancient bunny is known from a large amount of fossil specimens, some of which are almost complete skeletons, but most are fragmentary pieces of bone or teeth. Most of these Palaeolagus specimens likely met their end as the lunch of one of the many predators roaming the grass lands of prehistoric North America.

Post link

Toxodon

Mounted specimen on display at Harvard Museum of Natural History

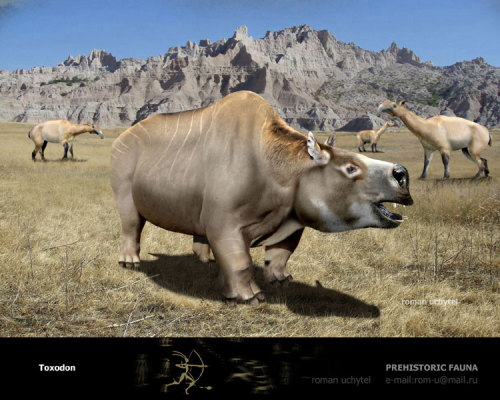

Reconstruction by Roman Uchytel

When: Pleistocene (~2.6 million to 16,000 years ago)

Where: South America

What:Toxodon is another one of the large herbivorous animals that roamed over South America. Charles Darwin purchased the skull of the first Toxodon known to the Old World during his journey on the Beagle. This skull was sent back to England were Sir Richard Own described it and named the animal Toxodon - ‘bow teeth' based on the curving nature of its gigantic molars. Soon complete skeletons of this amazing animal were known. The first interpratations reconstructed Toxodon as a semi-aquatic animal, much like the modern hippo, but later studies of the limbs and teeth of speciemens show this was incorrect. Toxodon was more the analogue of today’s rhinos than a hippo, a fully terrestrial animal with teeth well adapted for grinding tough plants in somewhat arid environments. Some Toxodon specimens have been found associated with arrowheads, showing that the first people to emigrate into South America had contact with these animals, and appear to have hunted them.

Where does Toxodon fit into the tree of life? Like its contemporary Macrauchenia (which you can see in the background of the reconstruction), its relationship to living mammals is uncertain. It falls into the larger clade of Notoungulata, literally Southern Ungulates, but the placment of this group within placental mammals is highly uncertain. They maybe have a close relationship with animals in the group Afrotheria but research in mammalian systematics is only beginning to be able to evaluate that, and other hypotheses. So what is Toxodon? We just don’t know.

Post link

Plesiadapis

Mounted specimen on display at the American Museum of Natural History, NYC

Reconstruction by Jay Matternes

When: Late Paleocene to Early Eocene (~ 61 - 55 millon years ago)

Where: North America and Europe

What:Plesiadapis is a small tree-dwelling mammal that was fairly comment in the late Paleocene of North America and Europe. This ancient mammalian taxon was about the size of a house cat, and though it may look very reminiscent of a squirrel it is a member of the primate family, as part of the larger group Plesiadapiformes. The latest research has shown that Plesiadapis was actually atypical for its namesake clade; this genus tended to be much larger than the average plesiadapiform and was not as well adapted for climbing as its smaller relatives, lacking a hand specially adapted for grasping. Plesiadapis could climb trees, but it would have been an arboreal quadruped, like the living squirrels, rather than a grasping locmotion as seen in most primates today. Another features reminiscent of rodents in Plesiadapis (and this is found in most of its kin) is its enlarged front teeth and the reduction or loss of teeth between these massive incisors and the grinding cheek teeth. Plesiadapis has been reconstructed as a frugivore - meaning its diet was primarily comprised of fruit. As much of North America and Europe was covered with lush sub-tropical forests during its range, Plesiadapis would have had quite a large selection of fruits to feed on.

The placement of Plesiadapiformes has been somewhat controversial in the past decade or so. There is uniform agreement that these animals fall somewhere near the group Euarchonta within placental mammals, but exactly where has been much debated. Euarchonta contains not only primates, but also the Scandentia (tree shrews) and Dermoptera (flying lemurs). Some early studies placed plesiadapiforms closer to the dermopterans than primates, but more recent studies tend to find this clade as either the first branches to spring off the primate lineage or just outside of Euarchonta itself, as stem taxa to all three orders. One last point to make things even more confusing! The group Plesiadapiformes? It is probably not a monophyletic (natural) group in reality. It is looking more and more like that some taxa previously grouped within Plesiadapiformes fall closer to living primates than to other taxa within the group.

To sum up that confusing mess, Plesiadapiformes are very important in understanding primate evolution, as at least some members of this assemblage of taxa are the first animals on the primate lineage. As this lineage includes me and you there is a lot of study focused on this group right now! Nice to see animals that are primarily paleocene taxa finally getting some attention.

Post link