#pompeii

So I’m using my college’s library resources to check out ebooks related to ancient, medieval, and early modern graffiti.

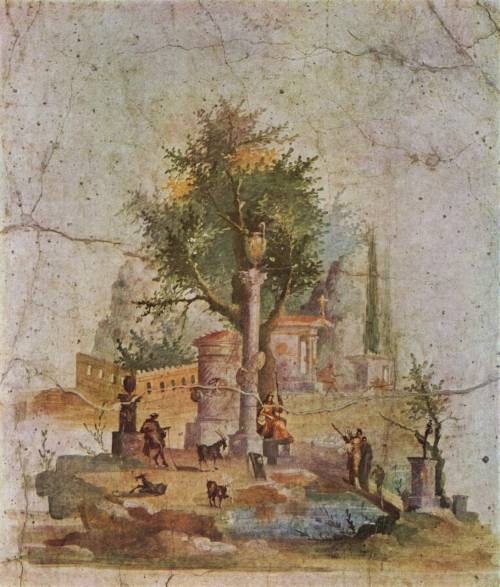

Most of us have seen things about the funny and obscene graffiti of Pompeii, but the underrated interesting thing about this subject isn’t what people wrote but the culture surrounding writing it. Both of the main books I’m looking at—Graffiti and thr Writing Arts of Early Modern England by Juliet Fleming, and Graffiti and the Literary Landscape in Roman Pompeii by Kristina Milnor—touch on this argument: for most of history, “graffiti” wasn’t understood, culturally, as transgressive in the way it is now.

We have this cultural taboo against writing on walls and other surfaces, even in our own homes. People throughout a lot of history didn’t have that. They wrote on things, and they wrote on them a lot. For example, in early modern England, it was normal to write all over walls and other surfaces in your house.

Another interesting thing is how much graffiti is quoting or parodying other things. A lot of Pompeii graffiti is in verse, and a lot of it is believed to be variations or parodies on quotes from popular plays and poems. In many cases, it’s stuff where we just… aren’t capable of getting the joke. (What I’m saying is, Romans liked to write memes everywhere.)

A lot of Roman graffiti is political. A lot of it is also personal. In Pompeii we see a lot of “Greetings/hello to [name].” I’m in love with how much graffiti involves responses and dialogue from multiple people. There’s an example of Pompeii graffiti that seems to be five women…just??? saying hello to each other on the same surface??? The Fleming book has an example of a riddle scratched into a mantelpiece (from the 1500’s iirc?) and an answer scratched below.

Also, if anyone remembers the “Halfdan” inscription in thr Hagia Sophia? The cool thing is that this isn’t an extraordinary thing at all. One of the most common formats of graffitied inscriptions is “[name] was here”/“[name] wrote this.” This transcends time and space and culture.

Milnor is inclined to call it “close to a fundamental human impulse,” and that makes my heart ache a little bit. How important it is to us, to say “I was here.”

“Cave canem” (beware of the dog) mosaic. From Casa di Orfeo, Pompeii. Now on display at the National Archaeological Museum.

Our t-shirt design inspired by this mosaic is available on Amazon and Redbubble (onelink) : https://geni.us/cavecanem2

Post link

Robotic dog will be on patrol in Pompeii

“We promise this isn’t an April Fools’ Day post.”

Nothing changed at all….