#quebec french

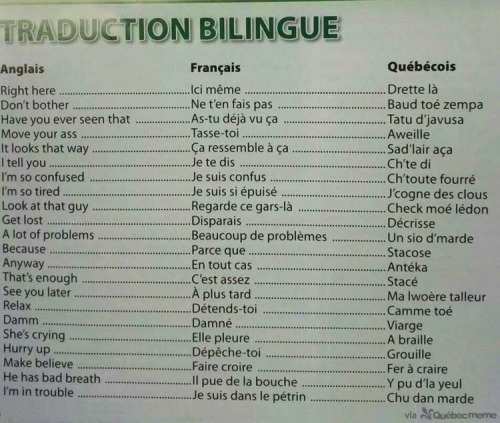

English to French to Québécois translations.

The accuracy is killing me lolYeah, when people say Canadians speak French, we really don’t. At all. We just call it French.

When I was younger I lived with a girl from Paris for two months, and every time she’d meet someone who spoke Quebecois they would speak to her thinking she’d understand it, and she would just nod and smile.

Why the fuck is it still called French?

Because its still french??? We have our own dialect and accent yes but it is still french. All over Québec there is different dialects. The french spoken in Montréal isn’t the same as the french spoken in Saguenay for example.

Je vais juste mettre la réponse de «l’insolente linguiste» ici. TLDR; C’est normal que ça ressemble pas à du français vu la façon dont ils l’écrivent. Et puis, c’est niaiseux de comparer la norme a un dialecte.. Le «Français» de cette image est aussi bien utilisé par les Québécois!

Okay, ça, c'est de la belle grosse merde. Ça doit faire 10 ans que cette image circule, au moins! Je l'ai démolie dans mon premier livre, d'ailleurs On confond toutes les variations linguistiques, c'est vraiment épouvantable. En plus, les versions «québécoises» sont écrites dans une orthographe fantaisiste qui stigmatise encore plus le français québécois. Pourquoi du côté québécois, c'est écrit «d'javusa», mais du côté français, c'est «déjà vu ça»? La seule différence, c'est qu'on fait pas le «é»!!! Sérieux, je peux pas croire que ça pogne encore, cette affaire-là.

Faque je me suis un peu amusée, pis j'ai fait l'équivalent, tiens, mais de l'autre bord:

QUÉBÉCOIS…………………………..FRANÇAIS

manger ……………………………….. bèketé

je m’en fous …………………………..jman tanpone

maison ………………………………… piôlle

eau ………………………………………flotte

dormir …………………………………. pionsser

fromage ………………………………. fromton

c’est parfait ……………………………céniquèlPrenez tous les commentaires qui vous viennent à l'esprit, comme, mettons, «mais ça s'écrit pas nécessairement comme ça» ou «mais c'est pas tous les Français qui parlent de même» ou «mais ça dépend du contexte», pis vous allez avoir tous les bons arguments pour l'image de merde.

@tepitome, arrête de dévaloriser la variante que parlent les québécois. Ça reste du français. Moi non plus quand les français se mettent à parler avec des variantes qui leur sont propres, j’comprends rien.

As someone who lives not too far from the Canadian border in New England, I honestly wish they taught the Québécois dialect either along with or instead of the Parisian French I learned in high school. And I say “Parisian French” because even in France there are so many other dialects. IMO there’s a lot of misguided ways of teaching and while i LOVED my main French teacher, I wish we all had focused on more of a worldwide/functional Francophone vocabulary instead of just what’s in France, and only the Capitol City at that.

Quick english summary of the response chloek3 included for my non-french-speaking followers:

The above image has been making the rounds for at least ten years and the way it transcribes the québécois phrases further stigmatizes that dialect of french. For instance, for “déjà vu ça” they write “d'javusa” even though the only difference is not pronouncing the é in déjà. (The examples included show ways that québécois people use the standard dialect while parisian french people use a non-standard version. When reading this picture, remember that 1. it’s not necessarily written like that, 2. not all french people speak the same, and 3. it depends on context.

Post link

An interesting question found its way into our inbox recently, asking about relative clauses in Swedish, and wondering whether their unique characteristics might pose a problem for some of the linguistic theories we’ve talked about on our channel. So if you want a discussion of syntax, Swedish, and subjacency (with some eye-tracking thrown in), this is for you!

So yes, there is a hypothesis that Swedish relative clauses break one of the basic principles by which language is thought to work. In particular, it’s been claimed that one of the governing principles of language isSubjacency, which basically says that when words move around in a sentence, like when a statement gets turned into a question, those words can’t move around without limit. Instead, they have to hop around in small skips and jumps to get to their destination. To make this more concrete, consider the sentence in (1).

(1) Where did Nick think Carol was from?

The idea goes that a sentence like this isn’t formed by moving the word “where” directly from the end to the beginning, as in (2). Instead, we suppose that it happens in steps, by moving it to the beginning of the embedded clause first, and then moving it all the way to the front of the sentence as a whole, shown in (3).

(2a) Did Nick think Carol was from where?

(2b) Where did Nick think Carol was from _?

(3a) Did Nick think Carol was from where?

(3b) Did Nick think where Carol was from _?

(3c) Where did Nick think _ Carol was from _?

One of the advantages of supposing that this is how questions are formed is that it’s easy to explain why some questions just don’t work. The question in (4) sounds pretty weird — so weird that it’s hard to know what it’s even supposed to mean. (The asterisk marks it as unacceptable.)

(4) *Where did Nick ask who was from _?

Theexplanation behind this is that the intermediate step that “where” normally would have made on its way to the front is rendered impossible because the “who” in the middle gets in its way. It’s sitting in exactly the spot inside the structure of the sentence that “where” would have used to make its pit stop.

More generally, Subjacency is used as an explanation for ‘islands,’ which are the parts of sentences where words like “where” and “when” often seem to get stranded. And one of the most robust kinds of island found across the world’s languages is the relative clause, which is why we can’t ever turn (5) into (6).

(5) Nick is friends with a hero who lives on another planet

(6) *Where is Nick friends with a hero who lives _?

Surprisingly, Swedish — alongside other mainland Scandinavian languages like Norwegian — seems to break this rule into pieces. The sentence in (7) doesn’t have a direct translation into English that sounds very natural.

(7a) Såna blommor såg jag en man som sålde på torget

(7b) Those kinds of flowers saw I a man that sold in square-the (gloss)

(7c) *Those kinds of flowers, I saw a man that sold in the square

So does that mean we have to toss all our progress out the window, and start from scratch? Well, let’s not be too hasty. For one, it’s worth noting that even the English version of the sentence can be ‘rescued’ using what’s called a resumptive pronoun, filling the gap left behind by the fronted noun phrase “those kinds of flowers.”

(8) Those kinds of flowers, I saw a man that sold them in the square

For many speakers, the sentence in (8) actually sounds pretty good, as long as the pronoun “them” is available to plug the leak, so to speak. At the very least, these kinds of sentences do find their way into conversational speech a whole lot. So, whether a supposedly inviolable rule gets broken or not isn’t as black-and-white as it might appear. What’s maybe a more compelling line of thinking is that what look like violations of these rules on the surface can turn out not to be, once we dig a little deeper. For instance, the sentence in (9), found in Quebec French, might seem surprising. It looks like there’s a missing piece after “exploser” (“blow up”), inside of a relative clause, that corresponds directly to “l'édifice” (“the building”) — so, right where a gap shouldn’t be possible.

(9a) V'là l'édifice qu'y a un gars qui a fait exploser _

(9b) *This is the building that there is a man who blew up

But that embedded clause has some very strange properties that have given linguists reasons to think it’s something more exotic. For one, the sentence in (9) above only functions with what’s known as a stage-level predicate — so, a verb that describes an action that takes place over a relatively short period of time, like an explosion. This is in contrast to an individual-level predicate, which can apply over someone’s whole lifetime. When we replace one kind of predicate with another, what comes out as garbage in English now sounds equally terrible in French.

(10a) *V’là l'édifice qu'y a un employé qui connaît _

(10b) *This is the building that there is an employee who knows

Interestingly, stage-level predicates seem to fundamentally change the underlying structures of these sentences, so that other apparently inviolable rules completely break down. For instance, with a stage-level predicate, we can now fit a proper name in there, which is something that English (and many other languages) simply forbid.

(11a) Y a Jean qui est venu

(11b) *There is John who came (cannot say out-of-the-blue to mean “John came”)

For this reason, along with some other unusual syntactic properties that come hand-in-hand, it’s supposed that these aren’t really relative clauses at all. And not being relative clauses, the “who” in (9) isn’t actually occupying a spot that any other words have to pass through on their way up the tree. That is, movement isn’t blocked like how it normally would be in a genuine relative clause.

Still, Swedish has famously resisted any good analysis. Some researchers have tried to explain the problem away by claiming that what look like relative clauses are actually small clauses — the “Carol a friend” part of the sentence below — since small clauses are happy to have words move out of them.

(12a) Nick considers Carol a friend

(12b) Who does Nick consider _ a friend?

But the structures that words can move out of in Swedish clearly have more in common with noun phrases containing relative clauses, than clauses in and of themselves. In (13), it just doesn’t make sense to think of the verb “träffat” (“meet”) as being followed by a clause, in the same way it did for “consider.”

(13a) Det har jag inte träffat någon som gjort

(13b) that have I not met someone that done

(13c) *That, I haven’t met anyone who has done

So what’s next? Here, it’s important not to miss the forest for the trees. Languages show amazing variation, but given all the ways it could have been, language as a whole also shows incredible uniformity. It’s truly remarkable that almost all the languages we’ve studied carefully so far, regardless of how distant they are from each other in time and space, show similar island effects. Even if Swedish turns out to be a true exception after all is said and done, there’s such an overwhelming tendency in the opposite direction, it begs for some kind of explanation. If our theory is wrong, it means we need to build an even better one, not that we need no theory at all.

And yet the situation isn’t so dire. A recent eye tracking study — the first of its kind to address this specific question — suggests a more nuanced set of facts. Generally, when experimental subjects read through sentences, looking for open spots where a dislocated word might have come from as they process what they’re seeing, they spend relatively less time fixated on the parts of sentences that are syntactic islands, vs. those that aren’t. In other words, by default, readers in these experiments tend to ignore the possibility of finding gaps inside syntactic islands, since our linguistic knowledge rules that out. And in this study, it was found that sentences like the ones in (7) and (13), which seem to show that Swedish can move words out from inside a relative clause, tend to fall somewhere between full-on syntactic islands and structures that typically allow for movement, in terms of where readers look, and for how long. This suggests that Swedish relative clauses are what you might call ‘weak islands,’ letting you move words out of them in some circumstances, but not in others. And this is in line with the fact that not all kinds of constituents (in this case, “why”) can be moved out of these relative clauses, as the unacceptability of the sentence in (14) shows. (In English, the sentence cannot be used to ask why people were late.)

(14a) *Varföri känner du många som blev sena till festeni?

(14b) Why know you many who were late to party-the

(14c) *Why do you know many people who were late to the party?

For reasons we don’t yet fully understand, relative clauses in Swedish don’t obviously pattern with relative clauses in English. At the same time, the variation between them isn’t so deep that we’re forced to throw out everything we know about how language works. The search for understanding is an ongoing process, and sometimes the challenges can seem impossible, but sooner or later we usually find a way to puzzle out the problem. And that can only ever serve to shed more light on what we already know!