#relative clauses

Relativization strategies

How do languages form relative clauses like “the man that ate bread went home”.

- Relative pronoun/particle/complementizer - “the man [that/whoate bread] went home”. Typical of Indo-European, Uralic and Semitic languages.

- Correlative relative (non-reduction) - “the man [who ate bread], [that man] went home or “the man [he ate bread] went home” - this strategy involves an anaphor, repeating the antecedent with a noun/pronoun. Pronoun retention is also lumped in here. This strategy occurs in Indo-Aryan languages (Hindi, Bengali, Punjabi, Gujarati, Marathi, etc.), in Mande languages (e.g Bambara in Mali), Yoruba, Lakhota, Warao, Xerente, Walpiri, etc.

- Nominalized/participial relative - “the [bread eating] man went home” or “the [bread eaten] man went home” - I lumped this two together because the behaviour is very similar - used in Turkic, Mongolic, Koreanic, Dravidian, and Bantu languages.

- Genitive relative - “[ate bread]’s man went home" - used in Sino-Tibetan, Khmer, Tagalog, Minangkabau, and Aymara.

- Relative affix - “the man [ate-REL bread] went home” - used in Seri, Northwest and Northeast Caucasian languages and Maale (Omotic).

- Adjunction - “the man [ate bread] went home”, with no overt marker just justapositions modifying the main clause. Used in Japanese, Thai, Shan, Lao, Malagasy.

- Internally headed relative - "[the man ate the bread] went home", the nucleous is in the relative clause itself. Used in Navajo, Apache, Haida.

If you know about the languages left in blank, please let me know!

Post link

I haven’t written anything for this blog for ages, but this is something I wrote for another one…

English has a lot of relatives. I don’t mean languages to which it is related, but rather relative clauses. I’m only going to focus here on some so-called restrictive relative clauses. An example is given in (1) (the relative clause is in bold).

(1) The wolf that ate grandma was in bed.

In (1), the relative clause helps us to identify which wolf we are referring to, i.e. out of all the wolves in context, we are referring to the one that ate grandma. In other words, the relative clause in (1) restricts the referent of the noun modified by the relative clause, in this case wolf.

There are quite a few types of relative clause which can be used to restrict the referent of a noun. Some of them look quite similar to one another but they behave in slightly different ways as we will see.

First of all, there are relative clauses introduced by relative pronouns (whoorwhich) and those introduced by that. Let’s call them wh-relatives and that-relatives respectively.

(2) a. The wolf that ate grandma was in bed.

b. The wolf which ate grandma was in bed.

The noun modified by a wh-relative or a that-relative can correspond to a number of different positions inside the relative clause. In (2), for example, the noun wolf corresponds to the subject of ate. However, it could correspond to the object, like in (3), or the object of a preposition, like in (4), as well.

(3) a. The wolf that we saw was in bed.

b. The wolf which we saw was in bed.

(4) a. The wolf that Red Riding Hood talked to was in bed.

b. The wolf which Red Riding Hood talked to was in bed.

c. The wolf to which Red Riding Hood talked was in bed.

Some people would say (4b) is not correct because it has a stranded preposition, and that (4c) is the correct version. However, we are interested in what English speakers actually do, not what some people think they should do. Interestingly, if we use a that-relative, like in (4a), we have no choice but to strand the preposition! (5) is not even acceptable to English grammar pedants! (* means unacceptable/ungrammatical).

(5) *The wolf to that Red Riding Hood talked was in bed.

English also has restrictive relative clauses introduced by neither a relative pronoun nor that. Let’s call these zero-relatives because there is nothing (zero) visible/audible to introduce them. The noun modified by a zero-relative can correspond to an object or the object of a preposition in a relative clause. Some examples are given in (6).

(6) a. The wolf we saw was in bed.

b. The wolf Red Riding Hood talked to was in bed.

So far, zero-relatives look just like wh-relatives and that-relatives except that the relative pronoun or that is missing. However, there is another difference. We saw in (2) that the noun modified by a wh-relative or a that-relative can correspond to the subject of the relative clause. However, this is not possible when the noun is modified by a zero-relative.

(7) *The wolf ate grandma was in bed.

In (7), the intended meaning is the one where wolf corresponds to the subject of ate. However, (7) is unacceptable/ungrammatical. To express this meaning, we would need to use a wh-relative or a that-relative instead.

We have seen that a noun modified by a zero-relative cannot correspond to the subject of a relative clause. There are other restrictive relative clauses where the modified noun can only correspond to the subject. These are the so-called reduced relatives.

(8) a. The wolf eating grandma has such big ears, eyes and teeth.

b. The person eaten by the wolf was grandma.

They are called reduced because they seem to be reduced versions of wh-relatives or that-relatives.

(9) a. The wolf which/that is eating grandma has such big ears, eyes and teeth.

b. The person who/that was eaten by the wolf was grandma.

However, various pieces of evidence suggest that the examples in (8) are not the results of bits of (9) being deleted. For example, there are acceptable reduced relatives with no acceptable ‘full’ counterpart. Therefore, reduced relatives are not literally reductions of full relatives.

(10) a. The creature resembling grandma is a wolf.

b. *The creature which/that is resembling grandma is a wolf.

Reduced relatives in English are formed using the participle forms of the verb: either the present participle, e.g. eating in (8a), or the passive participle, e.g. eaten in (8b). Even though the passive participle looks like the past participle in English, the evidence tells us that reduced relatives can be formed using the passive participle, but not the past participle.

(11) a. The wolf has eaten grandma.

b. *The wolf eaten grandma is in bed.

In (11a), eaten is a past participle (not a passive participle). If reduced relatives were formed using the past participle and if the noun modified by a reduced relative can only correspond to the subject of the relative clause, we would expect (11b) to be acceptable. However, it isn’t. This, among other things, tells us that it is the passive participle that is used to form this type of reduced relative.

There is a lot more to say, and we haven’t even mentioned all the types of relative clause that English has to offer! But that must wait for later. If I say anymore at present, I fear you might start to envy grandma.

(No grandmas were harmed in the writing of this blogpost… well, one was eaten, but the rest are fine)

I wrote this for the CamLangSci blog last month… I have been working on reconstruction in relative clauses quite a bit recently, so this represents one way of desaturating my brain. That is not to imply that it is a tedious topic – far from it. Reconstruction effects in relative clauses give us a fascinating clue about how these constructions are built and how our interpretive faculties ‘read’ such structures. I have tried to avoid technicalities and jargon as much as possible, and to keep this blog entry a reasonable length whilst also getting to the core of some very deep questions in current syntactic theory. So, let’s get started.

We’ll start by considering the following data (if two elements have the same subscript, it means that the two elements refer to the same individual; if the subscripts are different, the elements refer to different individuals. The * means that the sentence is ungrammatical).

(1) a. Samx likes the picture of himselfx.

b. *Samx likes the picture of himx.

c. Samx thinks that Rosie likes the picture of himx.

In (1a), himself must refer to Sam. In (1b), him must not refer to Sam but must refer to some other singular male individual (some speakers find (1b) acceptable (Reinhart & Reuland 1993), but I and most other people I have asked do not). (1c) is ambiguous: him can either refer to Sam (as shown by the subscripts) or to some other singular male individual. The pattern in (1) is traditionally captured by the Binding Conditions (Conditions A and B to be more precise) (Chomsky, 1981). The Binding Conditions are quite technical so I won’t go into them here. What is important is the pattern in (1).

What happens if we relativise picture of X, i.e. modify picture of X with a relative clause?

(2) a. The picture of himselfx that Samx likes is quite flattering.

b. ?/*The picture of himx that Samx likes is quite flattering.

c. The picture of himx that Samx thinks that Rosie likes is quite flattering.

As we can see, the pattern in (2) is exactly the same as in (1). This suggests that we are interpreting the head of the relative clause, i.e. picture of himself, in the object position of like, since then (2) can be interpreted in the same way as (1). This in turn suggests that the head of the relative clause originated inside the relative clause and was moved to the position in which it is pronounced. However, when it comes to interpreting (rather than pronouncing) the structure, we ‘reconstruct’ the movement and interpret the head of the relative clause in its original position (see Bianchi, 1999; Kayne, 1994; Schachter, 1973; Vergnaud, 1974). For example, (2a) is interpreted as (3), where the bold copy is the one being interpreted. Note that this bold copy is not pronounced.

(3) The picture of himselfx that Samxlikes(the)picture of himselfxis quite flattering.

The bold the is in brackets because technically the determiner the does not reconstruct with the head of the relative clause picture of himself (Bianchi, 2000; Cinque, 2013; Kayne, 1994; Williamson, 1987 on the so-called indefiniteness effect on the copy internal to the relative clause). Reconstruction thus captures the similarities between (1) and (2) in a straightforward way.

In (2), the head of the relative clause served as the subject of the main clause. What happens when it serves as the direct object of the main clause?

(4) a. *Mrs. Cottony hates the picture of himselfx that Samxlikes.

b. ?/*Mrs. Cottony hates the picture of himx that Samxlikes.

c. Mrs. Cottony hates the picture of himx that Samx thinks that Rosie likes.

If the head of the relative is picture of him, the pattern is the same as in (1) and (2), which suggests that reconstruction has taken place. However, (4a) is ungrammatical for all the speakers that I have asked (this result is highly significant given what is usually said in the literature). This result is unexpected, especially if reconstruction is available in (4b) and (4c). If reconstruction were available, picture of himself should be able to reconstruct to the direct object position of likes inside the relative clause where it could co-refer with Sam, just like in (3). However, the only interpretation available in (4a) is the ungrammatical one where himself is trying to co-refer with Mrs. Cotton suggesting that reconstruction is impossible.

The difference between (4a) and (2a) lies in whether there is an element in the main clause that himself could get its reference from. In (2a), there is no such element, so picture of himself is forced to reconstruct so that himself gets a reference. In (4a), there is an element, albeit an unsuitable one. This suggests that the Binding Condition which allows himself to get its reference from another element applies blindly/automatically: himself gets bound to Mrs. Cotton automatically, which prevents reconstruction occurring. Later on, when it is time to interpret the binding relation, we discover that we were wrong to have bound himselftoMrs. Cotton, but by this time it is too late to perform reconstruction. This suggests that interpretation of syntactic structure only happens after all syntactic operations have finished. If it didn’t, we might expect that we could repair the mistake in (4a) by reconstruction. However, this is not what we find.

The same effect is also found in other constructions. Based on Browning (1987: 162-165), Brody (1995: 92) shows that (5) is acceptable suggesting that picture of himself has reconstructed to the direct object position of buy (the example is slightly adapted).

(5) This picture of himselfx is easy to make Johnxbuy.

However, reconstruction is blocked if there is a potential element that himself could get its reference from, even if it turns out later to be unsuitable (Brody, 1995: 92).

(6) *Maryy expected those pictures of himselfx to be easy to make Johnxbuy.

We have only touched the surface on reconstruction in relative clauses here (there are more reconstruction effects and more subtleties that I have been working on but which would take too long to lay out here). What we have concluded is that reconstruction is generally available in relative clauses (at least in English). This tells us that relative clauses are constructed with a copy of the head of the relative clause inside the relative clause itself. The problem is how to choose which copies to interpret. It seems that there are structural conditions which force certain copies to be interpreted, i.e. the choice is not completely free. Explaining what these conditions are can thus provide a fascinating clue about how the human mind works (and how it doesn’t).

If you’re keen to find out more, Sportiche (2006) gives a good overview of reconstruction effects and Fox (2000) develops a nice account of how interpretation interacts with syntactic structure.

References

Bianchi, V. (1999). Consequences of Antisymmetry: Headed Relative Clauses. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Bianchi, V. (2000). The raising analysis of relative clauses: a reply to Borsley. Linguistic Inquiry,31(1), 123–140.

Brody, M. (1995). Lexico-Logical Form: A Radically Minimalist Theory. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Browning, M. (1987). Null Operator Constructions. PhD dissertation, MIT.

Chomsky, N. (1981). Lectures on Government and Binding. Dordrecht: Foris.

Cinque, G. (2013). Typological Studies: Word Order and Relative Clauses. New York/London: Routledge.

Fox, D. (2000). Economy and Semantic Interpretation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Kayne, R. S. (1994). The Antisymmetry of Syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Schachter, P. (1973). Focus and relativization. Language,49(1), 19–46.

Sportiche, D. (2006). Reconstruction, Binding, and Scope. In M. Everaert & H. van Riemsdijk (Eds.), The Blackwell Companion to Syntax. Volume IV (pp. 35–93). Oxford: Blackwell.

Vergnaud, J.-R. (1974). French relative clauses. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Williamson, J. S. (1987). An Indefiniteness Restriction for Relative Clauses in Lakhota. In E. J. Reuland & A. G. B. ter Meulen (Eds.), The Representation of (In)definiteness (pp. 168–190). Cambridge, MA.

I wrote this for another blog - essentially trying to introduce and work through some of the motivations for certain analyses of relative clauses without too much jargon…

Introduction

My research focuses on the syntax of relative clauses. A typical relative clause is a type of subordinate sentence which modifies a noun. For example,

(1) a. the book that I’m reading

b. that blog post you’ve written

c. the man who saw me

d. a type of subordinate sentence which modifies a noun

The clause in bold is traditionally called the relative clause. They are theoretically interesting for a number of reasons. Some syntactic ones are: they are optional, i.e. nouns do not require a relative clause; the noun being modified seems to play a role in both the main clause and the relative clause; relative clauses resemble other constructions to a greater or lesser extent, e.g. interrogatives, possessives, etc.

The head of the relative

One of the major debates in the syntax of relative clauses lies in where we say the noun being modified originates in the syntactic structure (I will call this noun the relative head from now on). Consider the following example:

(2) You wrote the book that I’m reading.

Intuitively the relative head ‘book’ is the direct object of the main clause verb ‘write’. We also understand that ‘book’ is the direct object of the relative clause verb ‘read’. How can it be two things at once?

One option is to say that ‘book’ is base-generated, i.e. enters the syntactic structure, as the direct object of ‘write’ and is co-indexed with a relative pronoun in the relative clause (if two items are co-indexed, it basically means they refer to the same thing). This relative pronoun may be ‘who’, ‘which’ or silent (or ‘that’ depending on your analysis). Adopting the silent option and symbolising this silent pronoun as REL.PRO (for ‘relative pronoun’), the sentence in (2) would have the structure in (3) (the relative clause is placed in square brackets and the co-indexing is symbolised by the subscript ‘i’).

(3) You wrote the booki[REL.PROi that I’m reading]

But how does this capture the idea that ‘book’ is also the direct object of ‘read’? For this we say that the REL.PRO has moved from the direct object position of ‘read’ to the left edge of the relative clause. This gives the structure in (4).

(4) You wrote the booki[REL.PROi that I’m reading REL.PROi]

This captures our intuitions about how ‘book’ relates to the main clause and the relative clause. This is the sort of analysis found in Chomsky (1977) and Sauerland (2003), for example.

Another option would be to abandon co-indexing and say that ‘book’ is base-generated as the direct object of ‘read’. Instead of having a silent REL.PRO move to the left edge of the relative clause, the head of the relative itself moves (I use a subscript ‘1’ to symbolise that the two occurrences of ‘book’ are two copies of a single item rather than two independent items).

(5) You wrote the [book1 that I’m reading book1]

We would then say that the copy of ‘book’ in the direct object position of ‘read’ is not pronounced but is nonetheless present in the structure since we are able to interpret ‘book’ as being the direct object of ‘read’. The copy at the left edge of the relative clause is pronounced, giving the sentence in (2). This is the sort of analysis found in Kayne (1994).

The head, the ‘the’ and the relative clause

The type of relative clause we have been looking at is called a restrictive relative because it restricts the possible denotation of the noun. For example, (6) means that you wrote something and that something is a book AND that something is being read by me. In other words, the direct object of ‘write’ has to satisfy both the condition of being a book and being something that I’m reading. It allows you to distinguish this book from one that I’m not reading.

(6) You wrote the book that I’m reading.

To capture this, we say that the head of the relative and the relative clause are in the scope of the determiner ‘the’.

(7) [the [book that I’m reading]]

This can be capture in the syntactic structure by saying that [book that I’m reading] forms a constituent which excludes the determiner ‘the’. Now we have an interesting problem: ‘the’ appears with nouns, not clauses, which might suggest the following structure.

(8) [the [book [that I’m reading]]]

In this structure, ‘the’ requires a noun and so selects ‘book’. The relative clause modifies ‘book’ and so attaches to ‘book’. But there is evidence suggesting that the presence of ‘the’ is tied to the presence of the relative clause (a * means that the sentence is ungrammatical).

(9) a. London is beautiful.

b. *The London is beautiful.

c. The London that I remember is beautiful.

d. *London that I remember is beautiful.

A proper name, for example, ‘London’, cannot ordinarily appear with ‘the’ (hence the difference between (9a) and (9b)). However, when a proper name is modified by a relative clause, ‘the’ must appear (hence the difference between (9c) and (9d)). This suggests that ‘the’ requires the relative clause and not the noun! The following structure captures this idea (see Kayne, 1994).

(10) [the [[book] that I’m reading]]

Now, we have to come up with a way of relating ‘the’ to the head of the relative ‘book’, unless we want to abandon the idea that ‘the’ typically appears with nouns (an idea which might not be as crazy as it sounds). We could say that ‘the’ and ‘book’, by virtue of being close enough to each other in some non-technical sense, can enter into a relationship. Note that ‘book’ does not have a determiner of any kind. This is unusual in English.

(11) a. *I like book.

b. *Book is good.

We could therefore say that ‘book’ has an empty position for a determiner (I’ll call it D) that enters into a relationship with ‘the’ (see Bianchi, 2000).

(12) [the [[D book] that I’m reading]]

We can now make a prediction: if some other element occupies this D position, ‘the’ cannot form the required relationship and the sentence will be ungrammatical. A preposed genitive competes with ‘the’ in English, as seen in (13).

(13) a. the book

b. Bob’s book

c. *the Bob’s book

Now, if a preposed genitive occupies the D position that ‘the’ is aiming to form a relationship with, there will be trouble because ‘the’ and a preposed genitive cannot both be related to this same position, as seen in (13c). If ‘Bob’s’ is present, ‘the’ cannot be, but if ‘the’ is absent, the relative clause must be absent too. This accounts for why (14) is ungrammatical.

(14) *You wrote Bob’s book that I’m reading.

The only way to say what (14) intends to say is not to prepose the genitive, as in (15).

(15) You wrote the book of Bob’s that I’m reading.

Since ‘Bob’s’ no longer occupies D, ‘the’ is free to form a relationship with D and the sentence is grammatical.

Conclusion

That concludes this introduction to the syntax of relative clauses. We have seen that relative clauses are complex and have quite a counter-intuitive structure once we delve into the systematic patterns of grammaticality and ungrammaticality manifested in English. But that is the way of things – language is a part of the natural world and, just as theoretical physics is dumbfounding us with discoveries into the weird and wonderful nature of the physical universe, so too can theoretical linguistics make discoveries about the underlying structures of our linguistic universe (and all that without a Large Hadron Collider … for now).

References

Bianchi, V. (2000). The raising analysis of relative clauses: a reply to Borsley. Linguistic Inquiry,31(1), 123–140.

Chomsky, N. (1977). On Wh-Movement. In P. Culicover, T. Wasow, & A. Akmajian (Eds.), Formal Syntax (pp. 71–132). New York: Academic Press.

Kayne, R. S. (1994). The Antisymmetry of Syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sauerland, U. (2003). Unpronounced heads in relative clauses. In K. Schwabe & S. Winkler (Eds.), The Interfaces: Deriving and interpreting omitted structures (pp. 205–226). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

An interesting question found its way into our inbox recently, asking about relative clauses in Swedish, and wondering whether their unique characteristics might pose a problem for some of the linguistic theories we’ve talked about on our channel. So if you want a discussion of syntax, Swedish, and subjacency (with some eye-tracking thrown in), this is for you!

So yes, there is a hypothesis that Swedish relative clauses break one of the basic principles by which language is thought to work. In particular, it’s been claimed that one of the governing principles of language isSubjacency, which basically says that when words move around in a sentence, like when a statement gets turned into a question, those words can’t move around without limit. Instead, they have to hop around in small skips and jumps to get to their destination. To make this more concrete, consider the sentence in (1).

(1) Where did Nick think Carol was from?

The idea goes that a sentence like this isn’t formed by moving the word “where” directly from the end to the beginning, as in (2). Instead, we suppose that it happens in steps, by moving it to the beginning of the embedded clause first, and then moving it all the way to the front of the sentence as a whole, shown in (3).

(2a) Did Nick think Carol was from where?

(2b) Where did Nick think Carol was from _?

(3a) Did Nick think Carol was from where?

(3b) Did Nick think where Carol was from _?

(3c) Where did Nick think _ Carol was from _?

One of the advantages of supposing that this is how questions are formed is that it’s easy to explain why some questions just don’t work. The question in (4) sounds pretty weird — so weird that it’s hard to know what it’s even supposed to mean. (The asterisk marks it as unacceptable.)

(4) *Where did Nick ask who was from _?

Theexplanation behind this is that the intermediate step that “where” normally would have made on its way to the front is rendered impossible because the “who” in the middle gets in its way. It’s sitting in exactly the spot inside the structure of the sentence that “where” would have used to make its pit stop.

More generally, Subjacency is used as an explanation for ‘islands,’ which are the parts of sentences where words like “where” and “when” often seem to get stranded. And one of the most robust kinds of island found across the world’s languages is the relative clause, which is why we can’t ever turn (5) into (6).

(5) Nick is friends with a hero who lives on another planet

(6) *Where is Nick friends with a hero who lives _?

Surprisingly, Swedish — alongside other mainland Scandinavian languages like Norwegian — seems to break this rule into pieces. The sentence in (7) doesn’t have a direct translation into English that sounds very natural.

(7a) Såna blommor såg jag en man som sålde på torget

(7b) Those kinds of flowers saw I a man that sold in square-the (gloss)

(7c) *Those kinds of flowers, I saw a man that sold in the square

So does that mean we have to toss all our progress out the window, and start from scratch? Well, let’s not be too hasty. For one, it’s worth noting that even the English version of the sentence can be ‘rescued’ using what’s called a resumptive pronoun, filling the gap left behind by the fronted noun phrase “those kinds of flowers.”

(8) Those kinds of flowers, I saw a man that sold them in the square

For many speakers, the sentence in (8) actually sounds pretty good, as long as the pronoun “them” is available to plug the leak, so to speak. At the very least, these kinds of sentences do find their way into conversational speech a whole lot. So, whether a supposedly inviolable rule gets broken or not isn’t as black-and-white as it might appear. What’s maybe a more compelling line of thinking is that what look like violations of these rules on the surface can turn out not to be, once we dig a little deeper. For instance, the sentence in (9), found in Quebec French, might seem surprising. It looks like there’s a missing piece after “exploser” (“blow up”), inside of a relative clause, that corresponds directly to “l'édifice” (“the building”) — so, right where a gap shouldn’t be possible.

(9a) V'là l'édifice qu'y a un gars qui a fait exploser _

(9b) *This is the building that there is a man who blew up

But that embedded clause has some very strange properties that have given linguists reasons to think it’s something more exotic. For one, the sentence in (9) above only functions with what’s known as a stage-level predicate — so, a verb that describes an action that takes place over a relatively short period of time, like an explosion. This is in contrast to an individual-level predicate, which can apply over someone’s whole lifetime. When we replace one kind of predicate with another, what comes out as garbage in English now sounds equally terrible in French.

(10a) *V’là l'édifice qu'y a un employé qui connaît _

(10b) *This is the building that there is an employee who knows

Interestingly, stage-level predicates seem to fundamentally change the underlying structures of these sentences, so that other apparently inviolable rules completely break down. For instance, with a stage-level predicate, we can now fit a proper name in there, which is something that English (and many other languages) simply forbid.

(11a) Y a Jean qui est venu

(11b) *There is John who came (cannot say out-of-the-blue to mean “John came”)

For this reason, along with some other unusual syntactic properties that come hand-in-hand, it’s supposed that these aren’t really relative clauses at all. And not being relative clauses, the “who” in (9) isn’t actually occupying a spot that any other words have to pass through on their way up the tree. That is, movement isn’t blocked like how it normally would be in a genuine relative clause.

Still, Swedish has famously resisted any good analysis. Some researchers have tried to explain the problem away by claiming that what look like relative clauses are actually small clauses — the “Carol a friend” part of the sentence below — since small clauses are happy to have words move out of them.

(12a) Nick considers Carol a friend

(12b) Who does Nick consider _ a friend?

But the structures that words can move out of in Swedish clearly have more in common with noun phrases containing relative clauses, than clauses in and of themselves. In (13), it just doesn’t make sense to think of the verb “träffat” (“meet”) as being followed by a clause, in the same way it did for “consider.”

(13a) Det har jag inte träffat någon som gjort

(13b) that have I not met someone that done

(13c) *That, I haven’t met anyone who has done

So what’s next? Here, it’s important not to miss the forest for the trees. Languages show amazing variation, but given all the ways it could have been, language as a whole also shows incredible uniformity. It’s truly remarkable that almost all the languages we’ve studied carefully so far, regardless of how distant they are from each other in time and space, show similar island effects. Even if Swedish turns out to be a true exception after all is said and done, there’s such an overwhelming tendency in the opposite direction, it begs for some kind of explanation. If our theory is wrong, it means we need to build an even better one, not that we need no theory at all.

And yet the situation isn’t so dire. A recent eye tracking study — the first of its kind to address this specific question — suggests a more nuanced set of facts. Generally, when experimental subjects read through sentences, looking for open spots where a dislocated word might have come from as they process what they’re seeing, they spend relatively less time fixated on the parts of sentences that are syntactic islands, vs. those that aren’t. In other words, by default, readers in these experiments tend to ignore the possibility of finding gaps inside syntactic islands, since our linguistic knowledge rules that out. And in this study, it was found that sentences like the ones in (7) and (13), which seem to show that Swedish can move words out from inside a relative clause, tend to fall somewhere between full-on syntactic islands and structures that typically allow for movement, in terms of where readers look, and for how long. This suggests that Swedish relative clauses are what you might call ‘weak islands,’ letting you move words out of them in some circumstances, but not in others. And this is in line with the fact that not all kinds of constituents (in this case, “why”) can be moved out of these relative clauses, as the unacceptability of the sentence in (14) shows. (In English, the sentence cannot be used to ask why people were late.)

(14a) *Varföri känner du många som blev sena till festeni?

(14b) Why know you many who were late to party-the

(14c) *Why do you know many people who were late to the party?

For reasons we don’t yet fully understand, relative clauses in Swedish don’t obviously pattern with relative clauses in English. At the same time, the variation between them isn’t so deep that we’re forced to throw out everything we know about how language works. The search for understanding is an ongoing process, and sometimes the challenges can seem impossible, but sooner or later we usually find a way to puzzle out the problem. And that can only ever serve to shed more light on what we already know!

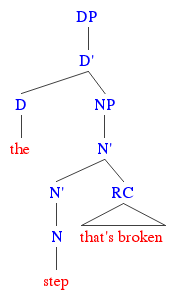

Inour episode on relative clauses, we focused on restrictive relative clauses, which we argued behave a lot like adjectives — specifically, intersective adjectives like “broken” and “curly.” In other words, if we think of both relative clauses and the nouns they combine with as sets, then the meanings we get out of connecting them together are whatever those sets share in common, or their intersection.

(1) “the broken step” ≈ “the step that’s broken”

And it makes sense to suppose that these kinds of relative clauses typically sit inside noun phrases, somewhere that’s neither too far up nor too far down the tree. After all, we can freely separate a relative clause from its host noun with a prepositional phrase, as in “the step in the middle of the staircase that’s broken,” suggesting the relative clause isn’t all that close to it to begin with. At the same time, the definite article seems to have a significant influence over everything that follows it, since out of all the steps and all the things that are broken, “the” picks out the one thing that’s both; this suggests that the relative clause is somewhere below the determiner.

But this isn’t the only kind of relative clause we find. If you want some more kinds of relative clauses, check below:

Consider the following sentence:

(2) Luke’s dad, who used to be a cheerleader, is also quite the prankster.

It doesn’t look like the relative clause “who used to be a cheerleader” is really restricting the meaning of “Luke’s dad.” In fact, if anything, it seems to be adding to it! In this case, we have what’s called a non-restrictive relative clause, which is often fenced off from the rest of the sentence with a slight pause (represented with commas).* And while restrictive relative clauses are generally thought of as combining meaningfully with the words around them, many linguists view non-restrictive relative clauses as being semantically separate from the rest of the sentence, as a kind of afterthought. The meaning of the sentence above, then, could be paraphrased like this:

(3) Luke’s dad is quite the prankster. Note that he used to be a cheerleader.

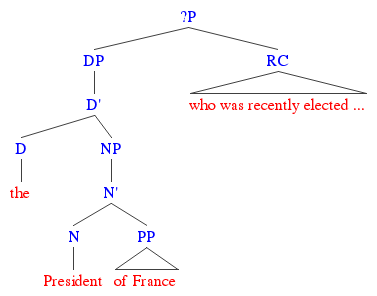

And non-restrictive relative clauses seem to be free of the influence of determiners. A sentence like “The President of France, who was recently elected to office, is relatively young” doesn’t seem to imply that there are a whole bunch of French Presidents, and that only one of them was recently elected; instead, the relative clause applies to everything that came before it — the whole of “the President of France,” including the definite article. So, we get a different picture of what these sorts of structures probably look like, with the non-restrictive relative clause attaching to some node sitting above the determiner phrase.

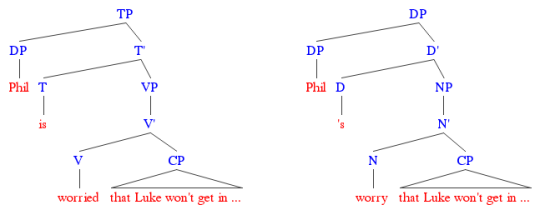

Finally, we see another brand of embedded clause that, on the surface, looks an awful lot like what we’ve seen already. Consider the following noun phrase:

(4) Phil’s worry that Luke won’t get into college

Notice, though, that unlike the relative clauses we’ve been seeing up until now, this one doesn’t have any gap in it; that is, it can stand on its own as a complete sentence.

(5) Luke won’t get into college.

These kinds of embedded clauses, which provide content to the nouns they modify, are known as complement clauses, because they look so much like the complements of verbs like “worry” and “claim” — found in full sentences like the one below.

(6) Phil’s worried that Luke won’t get into college.

And given their name, it seems reasonable to suppose they occupy a spot inside noun phrases that’s similar to the complements of these kinds of verbs, cozying up right next to the head of the phrase.

However, it turns out that this can’t quite be true. Not only are complement clauses able to follow restrictive relative clauses, it actually sounds kind of weird when they don’t! (And this is a pattern that holds across languages.)

(7a) I don’t believe the rumour that I heard this morning that he’ll move.

(7b) ??I don’t believe the rumour that he’ll move that I heard this morning.

Complement clauses even seem to work well after non-restrictive relative clauses.

(8) There’s a rumour, which I heard this morning, that he’ll be moving.

So complement clauses end up looking a lot like more some species of non-restrictive relative clauses than anything else (including real complements), meaning they probably connect up to a part of the tree that’s higher up than your average relative clause.

It really does take all kinds!

*Some insist on another difference between restrictive and non-restrictive relative clauses: that while either one may use relative pronouns like “who” or “where,” only restrictive relative clauses may use “that,” while only non-restrictive relative clauses may use “which.” But there are plenty of counter-examples to this supposed rule, as in Nietzsche’s famous quote “That which does not kill us makes us stronger.” And though non-restrictive relative clauses using “that” are very much an endangered species, they can still be spotted in the wild from time to time.

We can put whole clauses inside other phrases, but what does that do to their structure and their meaning? In this week’s episode, we take a look at the syntax and semantics of relative clauses: how these clauses kind of look like adjectives; how using them creates islands from which words can’t escape; and how moving things around in them throws semantic variables into the sentence setup.

Looking forward to hearing what everyone has to say! ^_^