#screenwriting

Yes, loglines are easy. If you write them first.

Logline instructions usually include describing the protagonist, his challenge, and the course he takes to accomplish his goal. It is often recommended that you describe the antagonist as well.

That should all be wrapped up in one tidy sentence that indicates tone and genre, polished up all shiny and sexy enough to pop off the page. A whole trailer, right there, in twenty words or less.

If you can’t do that, it isn’t because you’re bad at loglines.

Logline problems are really story problems. A story that resists being loglined has not been wrestled to the ground yet. It isn’t sharply focused and you probably don’t have a steeply escalating second act.

My first writing teacher at UCLA, Paul Chitlik, who is wonderful and wrote a wonderful book which I highly recommend, Rewrite, starts with weeks of logline development. Because…

It is incredibly easy to identify the weaknesses in your story before you’ve spent twelve weeks writing it.

If writing your logline feels like herding cats, stop what you’re doing and go back to your story. Is it about someone who has no choice but to do something very difficult that he is uniquely unsuited to do? What is his plan to do it?

- Long ago in a galaxy far away, a simple farm boy must train as a Jedi warrior to defeat an evil empire.

If your logline is more like, “A high school football player moves to a small town to live with his grandmother and struggles to be accepted at his new school.”, I can tell that your story isn’t clear to you yet, because it should be way more specific than that.

- A high school football star has to join the cheerleading squad to protect his sports scholarship.

- A high school football star falls for a nerd girl and has to become valedictorian to follow her to an Ivy League college.

Specific, rather than atmospheric. If you nail down your logline BEFORE you write, it won’t bite you in the butt later.

Writers of spec screenplays often make the mistake of explaining things to readers, as if there is no other way of being understood.

Subtext is the opposite of that.

Since the easiest way to demonstrate this is to write two scenes, one with subtext and one without, that is what I did.

See if you can guess which one has subtext.

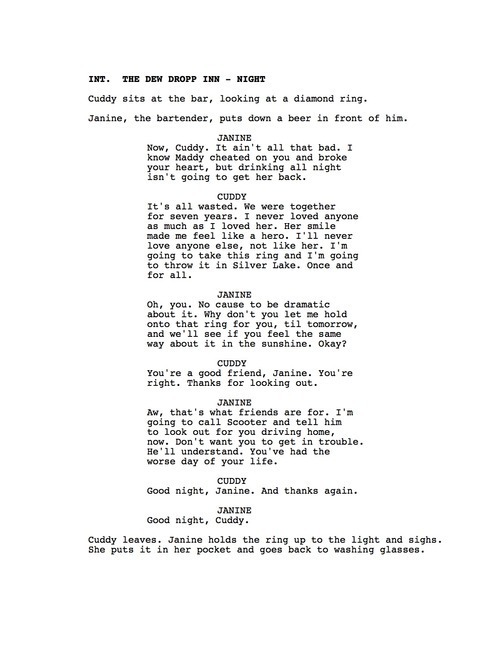

1.

2.

Both scenes establish that Janine and Cuddy are friends, that Maddy has cruelly broken Cuddy’s heart and that Janine ends up with the ring.

But the first scene also establishes that Janine is a smart girl who can handle herself, that Cuddy is prone to bad decisions and getting into trouble, and that Janine is not above a little deviousness, but ultimately she will do the right thing by calling for help.

So the answer is Scene 1.

That is subtext.

That is all.

Ideally, when you enter a competition, you win it. If you don’t, your consolation prize is some knowledgeable feedback about why someone else won.

But when you’re reading for a competition, you aren’t a critic. We can’t be brutally honest about what doesn’t work in your script. Our function is to be as helpful as possible, which occasionally produces euphemism.

If you didn’t get past the first round and you want to know what your feedback really means, here is a translation.

Euphemism: The concept didn’t gel.

Your story isn’t about a person who fights through obstacles of increasing difficulty, including his crippling flaw, to get something he can’t live without.

The fix: Nail down your story so it is about someone doing something difficult for a compelling reason.

Euphemism: The dialogue is expository.

Your lines explain what’s going on, who everyone is and why they’re doing what they’re doing.

The fix: Write dialogue as if it’s the reader’s job to figure all that stuff out. Compose most dialogue to build character instead of reveal plot. Focus on subtext. Readers love subtext.

Euphemism: The stakes are low.

Your plot never establishes why your protagonist needs this thing he needs so much that if he doesn’t get it, it would be a catastrophe.

The fix: Get rid of all his safety nets. Write with an eye to increasing how badly this enterprise can go wrong.

Euphemism: The protagonist is not sympathetic.

You wrote a character the reader doesn’t care about. Your protag does not have to be likable, but he has to be relatable.

The fix: Give your protag a deep, authentic flaw and construct his obstacles to challenge him right where he’s weakest.

Euphemism: Low conflict.

You’re much too easy on your protag.

The fix: To up your conflict, brainstorm about the worst possible thing that could happen to your protag in his quest. The tallest hurdle. The biggest betrayal. The most devastating setback. Then do that.

Euphemism: The structure is loose.

Every scene does not add something.

The fix: Every scene should complicate matters rather then illuminate them or set them up or resolve them. Go through your scenes and find the ones that don’t throw another wrench into the works. Tighten your structure by lumping them together into scenes that matter, or get rid of them.

Did you get a euphemistic piece of feedback you can’t decipher? I would love to hear it.

It is an illusion that a screenplay is a transcription of the movie in your head.

It is as impossible to write a movie as it is to write a photograph.

It is only possible to write a story.

THE HOT GIRLFRIEND PRIZE

She waits, over there, until it is time for her to be awarded to the protagonist in recognition for his achievements.

JUST THE WORLD’S BEST EVER MOMWIFE

She cares so much. She gets concerned. She just wants to help. She has never needed a drink in her entire life.

MISS READY, WILLING AND ABLE

Whether she’s GIRL 1, PILATES TEACHER or the CUTE CASHIER, her only function is to come on to the protag like she just got sprung from Litchfield Prison.

None of these characters resemble human beings.

Don’t give valuable page space to them. Thrill readers by putting a different spin on minor characters. Hold the cheese.

Double check these when you proof your spec. They pop up all the time.

- Loose/Lose

- Peek/Peak

- Chord/Cord

- Rein/Reign

- Bare/Bear

- Brake/Break

My husband and I watched The Place Beyond the Pines on VOD yesterday after we came back from the US Open.

When it broke into the third act for the third time, he said, “I think this movie is going into a fifth set.”

That about covers it.

EXT. THICK WOODS - NIGHT (or DAY, either one)

PANTING. Feet RUNNING and STUMBLING.

A GIRL (18-24) races for her life from an UNSEEN PURSUER.

She DIES. With a SCREAM.

And then we switch to somewhere else and meet the protagonist doing something mundane.

If you have written this, you are NOT ALONE. Word to the wise.

Good conflict is when people want mutually exclusive, life-changing things.

GOOD CONFLICT:

Jenny’s father wants her to quit school so she can nurse her chronically ill grandmother and he can keep his job as a long-haul truck driver. Jenny wants him to sign a letter of consent for a prestigious military academy so she can learn to fly jets.

- Only one of them is going to get what they want, and it is life-changing in both directions.

- Each of them needs the other to back down so they can get what they want.

- Someone is going to win and someone is going to lose.

BAD CONFLICT:

Jenny’s father wants her to nurse her grandmother. Jenny wants to win a baking competition so she can open her own cake shop.

- They want different things, but they can figure out how to compromise.

- This isn’t the only way to open a cake shop. There’s not a lot at stake.

- There’s no timelock on it. Jenny can open a cake shop tomorrow or six months from now or next year. No tension.

Give good conflict to up your game.

To get you past the first wall of readers.

Most spec scripts submitted to competitions and festivals look alike in ways that these gifs and articles encourage you to avoid.

That’s about it.

BAD PACING:

There is an idea set up that something is going to happen, and then nothing dramatic happens. And that keeps looping.

GOOD PACING:

Something is about to happen. Something completely unexpected happens. Then, CAR! Then garbage cans are flying everywhere. New problem. And the lawn still isn’t mowed.

The most convincing argument I can make against starting your spec with the backstory and then jumping forward in time is this:

Casablanca doesn’t open in Paris.

Start in the now and set up your now problem. Use the backstory to escalate in your second act. It will elevate your game like crazy.

I am married to a musician and I hear lots and lots of music, new and old. There are fifty hours of Later with Jools Holland on my DVR right now.

But I am still not familiar with your favorite band, so when I read song titles in your description lines, I don’t know what you’re talking about. And even if I did, it doesn’t convey any information to me. The odds on me being exactly on your wavelength about that music, supposing I do know it, are worse than a superfecta.

Unless you are making your own film, everything about movie music is someone else’s job.

Example:

I was at a screening of Flight, and there was a Q & A with Robert Zemeckis, and a woman said, “I was wondering about your choice to not have a musical score. How did you make that choice?” and he said, “Well, there was a score, and we labored over it, but the fact that you didn’t notice it means we did it really well.”

I’m assuming she wasn’t talking about “Sympathy for the Devil”, but I am damn sure John Gatins didn’t put that in the script.*

Anyway. Music just doesn’t translate very well to the page. If you have to describe it, do it in a conceptual way so it will mean roughly the same thing to both of us.

Exception:

The only time I’ve ever seen a specific song title achieve something positive was in a comedy, and it worked like a punchline.

*on an unrelated note: John Gatins was there, too. The script for Flight had been around for…I can’t remember, seven years? And one day the phone rings out of the blue, and it’s “Denzel is interested in making your movie.” So, there’s that.

It can’t be a revolutionary idea, but I’ve never read it in a book or been taught it specifically by any of my outstanding teachers, so I’ll just say it here.

Write your spec script to entertain your reader, not as the draft you’re going to shoot.

Consider how you read a novel, and how you direct your own head movie while you’re reading it. It’s exactly the same. The more room you leave for a reader to richly imagine how your story looks, the better off you are.

Your story sells your story in ways that using your words to direct, DP, cast and decorate the sets cannot.

Knock yourself out in your action lines, use your writer’s voice.

For example, everyone has a picture in their head of a seedy bar, it lives in the collective imagination. It’s a waste of words to discuss the dusty bottles on the shelves, the mismatched furniture and dirty windows. That’s a given.

If you want to make it into a thing beyond calling it “the worst bar in town”, which is acceptable, BTW, go at it from a crazy new direction that adds something interesting, like…the bartender traps a roach on the bar with a shot glass and leaves it there.

Now that is a seedy bar.

Passive voice, generic tracking shots, descriptions of things that the reader will do all the heavy lifting to imagine for themselves, those go under the heading of “it took me out of the read”, which loosely translated means, “It kept me from directing it in my head.”

This is not to say that your action lines should fill with flowing, novel-like prose. That is bad. Think in images, but summarize them in your own voice.

Describe your idea more and the set design less.

Found footage of my cat. Fade out.

Poe’s Law infers that there is no way for me to know what the pie chart looks like for Ironic Cat-Saving vs. The Book Said to Save a Cat on This Page vs. Cats Saved by Coincidence vs. Other, but it is not an SRS I’m talking about.

I read a lot of literal cats getting literally saved.

Not that it’s news anymore, this very useful piece is over two years old, but it is not an asset to have a spec that hoves directly to this particular beatsheet for the sake of hoving.

The principles in the 2005 book set out some good rules for an ironclad logline before you start writing and some mechanics to keep you from being digested by the boggy mire of your second act. It is not by any means a useless book, but anecdotal evidence supports the idea that specs written to succeed on the model have become recognizable, and not in a flattering way to the writer.

Sort of the way every single episode of Community turned into exactly the same episode of Community.

Sorry, cats.