#selves

I don’t have the courage to show you how different silence is when we’re together and when you’re alone.

Post link

desert shadow 31

play with fire – illuminate self

more playing with fire – exfoliate self

push-it pwf – separate selves

out-of-control pwf – disintegration of self

stop pwf – floating in the ether

reflect on pwf – integration of this new self

acceptance of this self – if able!

Ami is one of these selves

Post link

Within you there is a stillness and a sanctuary

to which you can retreat at any time

and be yourself.

~ Hermann Hesse

Post link

The Mind in Indian Philosophy II: Self and World

Last time, in Part I, we discussed how our minds represent things under the limiting conditions of sensibility. We began with the arguments of Kant on this topic; his philosophy of mind has many similarities with some much-older classical Indian philosophy.

Today we discuss some Indian philosophy of the self.

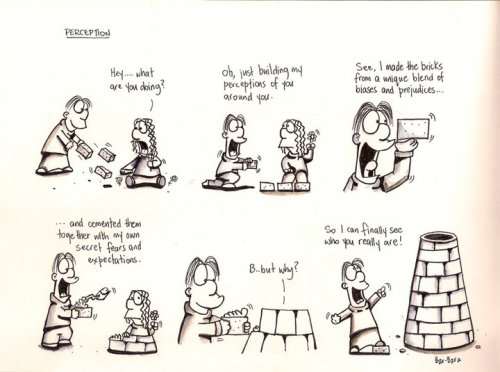

According to some philosophers, limitations of ourselves limit our knowledge of the external world. The basic idea is that if you change as a definite person—or if you never existed at all—the objects you perceive change as well because how you think, dream, and speak about objects is disunified.

For Arindam Chakrabarti (author of Realisms Interlinked; pictured), subjects and objects are intimately connected. A single ‘I’ of a mind must unify experiences over time to give nature to external reality (Nyāya-school arguments). A stable self achieves unification of objects by sustaining an objective time-order, carrying them in a coherent world in continued experience. So if a mind substantively changes and the single-self perspective dissipates, the objects housed in prior experience lose their structure.

Chakrabarti claims the mind can track the world because what is real about the world has the very nature of being knowable. Antirealists disagree and say this would render reality a product of the mind—a claim realists want to avoid! Sidestepping this challenge, Chakrabarti argues that subjects and objects must both be real for there to be real objects.

So are persisting subjects—selves—real?

Abhidharma Buddhist Vasubandhu claimed selves reduce to entities called ‘dhamas’. But these selves only hold ‘conventional’ existences. Pudgalavādins go further: they argue for the actual reality of persons. Nāgārjuna, in contrast, denied the existence of any fundamental object at all, including the self.

If there is no persistent self, there is no stable reality. As per Hume’s bundle theory, selves are just bundles of properties coming together. Objects, then, are bundles of properties coming together as well, appearing to us differently each time in representation under the limiting conditions of sensibility.

So here’s a scary thought.

Look at something you love, say, your pet. Ask: have you changed from five years or even 10 minutes ago? If you have, you better start firming up your reality; else you may have just lost a pet. The upshot is at least you gained a bundle of properties—and again; and again …

Post link