#philoblr

☀️ hello all, I’ve just finished my second year as a teacher and I wanted to say hello, I am still alive, still reading, still studying, still learning but now teaching too. I teach religion, philosophy and ethics in a big secondary school in a country park in England. I’d love to answer your questions about teaching or learning if you have any ☀️

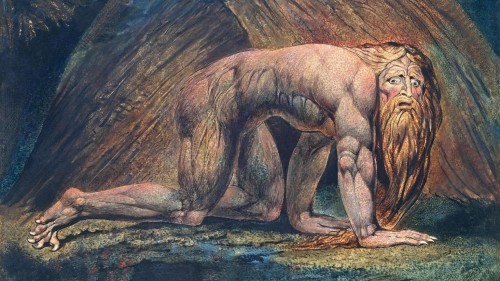

Mount Analogue

Here we bring to you a potent discussion on death and identity fromMount Analogue: A Novel of Symbolically Authentic Non-Euclidean Adventures in Mountain Climbing by René Daumal, described as follows:

‘In this novel/allegory the narrator/author sets sail in the yacht Impossible to search for Mount Analogue, the geographically located, albeit hidden, peak that reaches inexorably toward heaven. Daumal’s symbolic mountain represents a way to truth that “cannot not exist,” and his classic allegory of man’s search for himself embraces the certainty that one can know and conquer one’s own reality.’

In the passage below Father Sogol begins; the narrator replies.

‘With a little money in this galloping civilization of ours one can easily obtain the basic physical satisfactions. The rest is fraud. Fraud, ticks, and tricks — there’s our whole life, from diaphragm to cranium. My Superior was right: I suffer from an incurable need to understand. I don’t want to die without having understood why I lived. What about you? Have you ever been afraid of death?’

In silence I hunted around among my memories, deep memories where words had never before pried. And I spoke with difficulty. ‘Yes. When I was around six I heard something about flies which sting you when you’re asleep. And naturally someone dragged in the old joke: “When you wake up you’re dead.” The words haunted me. That evening in bed with the light out, I tried to picture death, the “no more of anything”. In my imagination I did away with all the outward circumstances of my life and felt myself confined in ever-tightening circles of anguish: there was no longer any “I” … What does it mean “I”? I couldn’t succeed in grasping it. “I” slipped out of my thoughts like a fish out of the hands of a blind man, and I couldn’t sleep. For three years these nights of questioning in the dark recurred fairly frequently. Then, on one particular night, a marvellous idea came to me: instead of just enduring this agony, try to observe it, to see where it comes from and what it is. I perceived that it all seemed to come from a tightening of something in my stomach, as well as under my ribs and in my throat. I remembered that I was subject to angina and forced myself to relax, especially my abdomen. The anguish disappeared. When I tried again in this new condition to think about death, instead of being clawed by anxiety, I was filled with an entirely new feeling. I knew no name for it — a feeling between mystery and hope.’

‘And then you grew up, went to school, and began to “philosophize”, didn’t you? We all go through the same thing. It seems that during adolescence a person’s inner life is suddenly weakened, stripped of its natural courage. In his thinking he no longer dares stand face to face with reality or mystery; he begins to see them through the opinions of “grown-ups”, through books and courses and professors. Still, a voice remains which is not completely muffled and which cries out every so often — every time its gag is loosened by an unexpected jolt in the routine. The voice cries out its great questioning of everything, but we stifle it again right away. Well, we already understand each other a little. I can admit to you that I fear death. Not what we imagine about death, for such fear is itself imaginary. And not my death as it will be set down with a date in the public records. But that death I suffer every moment, the death of that voice which, out of the depths of my childhood, keeps questioning me as it does you: “Who am I?” Everything in and around us seems to conspire to strangle it once and for all. Whenever the voice is silent — and it doesn’t speak often — I’m an empty body, a perambulating carcass. I’m afraid that one day it will fall silent forever, or that it will speak too late — as in your story about the flies: when you wake up, you’re dead.’

Did you feel that, too?

Post link

Being natural

We often speak about things being ‘natural’ or ‘more natural’ than other things. But what does this claim amount to? What does it mean to be natural?

Natural kinds

The concept of natural kind may be of service to us.

Something is of a natural kind if it can be grouped according to the structure of the natural world. The natural world can be ‘carved at the joints’ (Plato). Good theories, then, cut nature along these joints. Physics, for example, has it that electrons (meat) belong to the natural kind of fundamental particles.

Not so fast

However, human beings have blurred the boundaries of naturalness; for our actions and nature are in a constant interplay. At what point should something be considered artificial or arbitrary instead of natural?

Given our inquisitive and creative ways, we have used technology to synthesise vitamin C and new chemical elements (e.g., einsteinium [Es]). We have created ideal conditions for viruses (e.g., COVID-19) to spread globally—a virus which mutates via us. And while plants (e.g., GMO foods) can be grown from natural resources and share biological attributes with ‘wild’ flora, we have manipulated their DNA.

Are none of these examples natural in your eyes?

Philosophy to the rescue?

It’s tempting to think that only mind-independent things, entirely free of human involvement, are natural. But this approach eliminates a lot. Perhaps some metaphysics and philosophy of science can help us tighten up the definition.

For David Lewis there are ‘perfectly natural’ properties, like those described in physics and laws of nature; they are fundamental, simple, and intrinsic. But less-than-perfectly-natural things also exhibit degrees of naturalness; they are just more complex and abundant.

A more-liberal conception of naturalness is available in the work of Quine, whose natural kinds merely share natural properties. The scope of these natural kinds, however, is liable to becoming enormous. For example, if liquid is a natural kind, we haven’t exactly carved nature at the joints; a huge number of items fit this description.

Of course, philosophy didn’t rescue us.

⁂

A helpful concept here is social construction.

Humanscausally construct things (e.g., money) which are real but whose existences aren’t inevitable; for they are contingent on human decision-making. They are not natural but social kinds.

But we also constitutively construct things. These are things which necessarily stand in relations to human features and activity.

Take black and woman as two potential human kinds. Are they autonomously real, are they socially constructed, or are they both? While each is said to instantiate its own collection of biological properties, parts of their realities seem to depend on aspects of human culture, such as oppression and privilege, as well as causal factors, such as geography and gender norms.

(Pictured: What of nature survives the influence of ‘man’? [Francesco Paggiaro/Pexels])

Post link

Zombies

Do you believe in zombies? No, not those zombies.Philosophical zombies. They look just like people. In philosophical terms, they are physically identical to us. They have brains, blood flows around their bodies, they laugh at appropriate times, and if you pinch them, they are likely to say ‘Ow!’ Functionally, they are indistinguishable. However, they lack consciousness.

Most of us hope neither kind of zombie exists outside of fiction. While the place of regular zombies is in stories (usually horror), the place of philosophical zombies is in thought experiments (usually in philosophy of mind).

Now here’s why they matter: how do you prove that somebody—even somebody you’ve known for your entire life (e.g., a friend or someone with whom you’re in love)—is not a philosophical zombie?

Sure, you can sense the signals of their body (e.g., the sounds it makes, the light it reflects, the odours it gives off). But on what basis is your experience of them indicative of theirs?

Maybe you deduce mental life in them by analogy to yours. However, this takes a Cartesian leap of faith; for what is your philosophical argument? (Wittgenstein speaks of experience as a ‘beetle in the box’ which can only be inferred in someone else and not articulated, given private language’s inaccessibility.)

Maybe you can send them to a neurophysiologist to find ‘correlates of consciousness’; but this won’t prove experience alone.

In short: in your experience, yours is the only consciousness you are directly aware of.

And here’s the point: if we conceive of philosophical zombies as a logical possibility and believe that humans are distinguishable from them, it follows that we should refute physicalism as a means of explaining consciousness (David Chalmers). Why?

The very conceivability of zombies undermines explanations of consciousness in physicalism’s terms. (Remember, zombies share all our physical features.) We need something else to tell us apart from zombies since physicalism fails to show we are different.

The power of this argument, of course, rests on how conceivable we think zombies are. If you think zombies are conceivable, you have a problem in having no way of verifying others’ consciousness. If you don’t, you are burying your head in the non-philosophical sand until you come up with a reason why.

But what does this argument say about the power of philosophy?

⁂

Maybe it’s best not to think about zombies at all.

ED: Any zombies out there?

SHAUN: Don’t say that!

ED: What?

SHAUN: That.

ED: What?

SHAUN: That. The Z word. Don’t say it.

ED: Why not?

SHAUN: Because it’s ridiculous!

ED: [sighs and rolls his eyes] All right … Are there any out there, though?

—Shaun of the Dead(2004)

(Pictured: Zombies may imitate a smile but do they do not experience happiness. [cottonbro/Pexels])

Post link

‘Philosophy as “Great Art” - an Interview with Sophie Grace Chappell’

Exciting news: we just published our interview with Sophie Grace Chappell, the author of over 100 articles and the UK’s only transgender philosophy professor!

What’s her tip for getting into philosophy?

‘Read, read, read, read, read. When you’re doing philosophy, reading is the petrol in the tank; if you don’t read, you’re not going anywhere.’

And how does she assess the current situation for trans people in the UK?

‘This lack of visibility makes it too easy for transgender people to be monstered—we become a dark vague threat that no one actually knows, not people with faces but a “woke mob” or shadowy semi-criminalised lurkers in the Ladies’.’

Read the interview here.

Post link

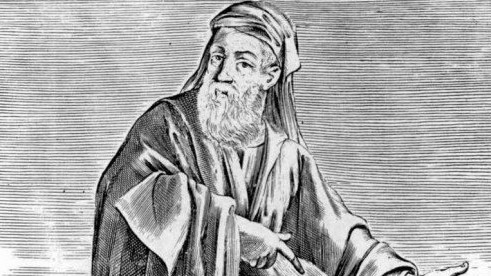

Ancient Science

Empedocles (pictured), born in around 494 BCE, spoke of four unchangeable elements—fire, air, water, and earth—which are pulled into war between two divine powers, Love and Strife. The result of this constant war is a unity of opposites. In comparison to our theories now, ideas from the past can sound bizarre—even fantastical. But we’re always in debt to the past.

We reap the benefits of generations of thinkers who philosophised and recorded their findings before us. Fragments of verse and poem were handed between generations. Songs were shared. Sheets were stained with quill, pencil, and pen. Even if only a fraction remains, we deduce and speculate.

Read more here.

Post link

‘Sometimes there’s so much beauty in the world, I feel like I can’t take it, and my heart is just going to cave in.’

Our analysis of American Beauty is two years old today You can read it here.

Post link

‘Grounders Gonna Ground’ - an Interview with Joaquim Giannotti

Smile if you love philosophy.

We interviewed rising star of metaphysics and ‘box-to-box metaphysician’ Joaquim Giannotti.

We hope you enjoy reading the interview as much as we enjoyed doing it.

Read more here.

Post link

The Philosophy of The Lord of the Rings

Two years ago we published this.

Are you holding on to something worth fighting for, too?

Post link

Studying black holes … with water

Let’s continue the fun with analogies! Below we expand on the use of a particular analogy from science which we briefly discussed in a recent article.

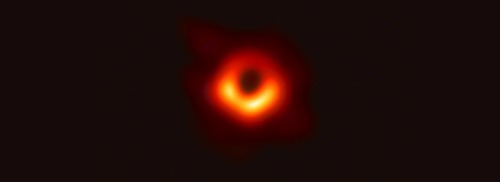

The image above depicts the supermassive black hole M87*, which sits at the centre of the M87 galaxy some 55 million light years away. It was compiled from radiofrequency signals collected across several telescopes over two years. It is the first of its kind.

In the image we are given direct evidence of Einstein’s theory of general relativity. The black hole is dark, as predicted, since radiation cannot escape black holes once it’s within their boundaries. Moreover, the accretion disk (bright) around the black hole, from which radiation is emitted, is of a lopsided-doughnut shape. This varied brightness results from intense gravitational warping. And, because of rotation, there’s a kind of relativistic Doppler effect going on: radiation is boosted in the direction of rotation towards Earth.

Now, here’s a funny thing of relevance to us: some scientists and philosophers claim we can study black holes by investigating … [drum roll] … plain old water. One argument goes like this.

Inanalogue experiments, involving surface-water waves, something about black holes is realisable in surface-water waves’ ‘white holes’. Therefore, black holes can be modelled by analogy because their models and the models of white holes are related by the assumptions they share.

The analogy is not defined by a material relation. Nonetheless, thermal aspects of Hawking radiation (named after Stephen Hawking), which is released at black-hole boundaries, can be simulated in water. The analogy owes itself to ‘syntactic isomorphism’ between models, whereby the relation is confirmed in a ‘Bayesian sense’.

‘Analogue simulation’ is still a powerful experimental tool which can be used in a similar sense to computer simulation. Isn’t this cool? Or are such analogies fraudulent in some way because they only offer crude and opaque approximations via models which are often proven incorrect?

(Picture credit: Event Horizon Telescope project.)

Post link

The Philosophy of Analogies

InThe Republic—after introducing ‘the analogy of the sun’, in which the idea of goodness ‘illuminates’ truth, and ‘the analogy of the divided line’—Plato presents ‘the Allegory of the Cave’ (depicted above).

Prisoners in an underground cave are chained by the neck and legs, their eyes fixed towards a wall onto which shadows are cast. Trusting their senses, these two-dimensional figures mark the prisoners’ reality. But this imaginary world does not represent the intelligible reality above it: the ‘world of ideas’.

Like the prisoners, we can only hope to understand reality by ascending out of the cave. Plato’s analogies are powerful. But is each story, the source, really consistent with its accompanying theory, the target of the analogy?

Read more here.

Post link

Why be rational?

During arguments we often hear people say, ‘You’re being irrational!’ The accusation is that the person being spoken to is failing to act in line with their best interests. However, according to Derek Parfit (1942–2017) in his classic text of contemporary utilitarianism, Reasons and Persons, this isn’t always a bad thing.

Self-interest

Parfit discusses ‘Self-interest Theory’ at length, the thesis of which is that we have most reason to do what we believe will work out best for ourselves. As such, it’s irrational to act in ways which we believe will make matters worse.

Parfit believes Self-interest Theory ultimately fails, using various examples along the way to show how rational acts aren’t always the best options.

The writer

Kate’s strongest desire is to write a good book. But she knows she might end up overworking herself (relatable), causing her exhaustion and depression.

She chooses not to write it (unrelatable).

Was this the right choice? Kate’s motives are rational on account of her hedonistic views: there’ll be less pain than pleasure. However, her life is bigger than weighing up pain and pleasure, which her rationality fails to identify.

The robber

A man breaks into my house. He orders I empty my safe of valuable possessions for him.

What shall I do? My family and I have seen the man’s car and its licence plate. This makes handing over my possessions irrational because he’ll probably kill us anyway. However, he’s threatening to kill my family if I don’t, which makes not doing so also irrational. There are no good rational options: I’m stuck.

Parfit suggests I drink a special solution conveniently sitting on the worktop next to me. It contains an irrationality-inducing drug. I drink it.

The man threatens me. But now I’m simply crazy—laughably so. ‘I love my children. Please kill them!’ I say. ‘Please carry on hurting me!’ The man loses his power over me, since I’m no longer rational, and flees.

In conclusion

Rationality is usually associated with guiding us towards our best interests. But it fails. And, as Parfit shows—albeit outlandishly—it pays to be ‘rationally irrational’.

⁂

Note: It’s not always distinctly clear what the magic mode of thought we call ‘rationality’ is meant to be. ‘Best interests’ in our definition is doing a lot of work here, for what are they?! Someone can always provide valid reasons for their actions, however harmful they are. For example, I might ask for my arm to be amputated because ‘I don’t like it anymore’. I might also watch my favourite football team play week upon week, despite how awful they make me feel on average, ‘to feel a connection’. There is nothing illogical per se about my motive in either case.

⁂

Also, according to a desire-fulfilment theory of reasons, what’s better for Kate is for her to fulfil her strongest desires. Will this enable Self-interest Theory to work?

(Photo credit: Roger Askew/Rex/Shutterstock)

Post link

A Life in Philosophy - With Constantine Sandis

It is with great pleasure that we bring to you our interview with illustrious philosopher Constantine Sandis. Constantine is a professor at the University of Hertfordshire. He has produced numerous publications spanning various topics across the philosophy of action and ethics. He even has a Wikipedia page.

We took the opportunity to probe the person inside the academic whilst also being sure to ask him what it’s like to be a real philosopher.

Read more here.

Post link

Faulkner and Wittgenstein on the privacy of experience

(Pictured: Addie Bundren [Beth Grant] in James Franco’s 2013 adaptionofAs I Lay Dying. [Millennium Films])

William Faulkner (1897–1962) was a Nobel laureate who authored classic novels The Sound and the Fury(1929) and As I Lay Dying (1930) as well as many more. Here we explain how his characters in As I Lay Dying broach the struggle of expressing private experience, a struggle also described in the works of philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein.

A poor and rural family slowly traverse the Mississippi countryside to bury their deceased wife and mother, Addie Bundren, miles away in town, meeting tribulations along the way.

In one chapter—from beyond the grave or in a flashback—Addie narrates her inability to express her private experiences of being a teacher, a wife, and a mother (ironically, using language). Whereas in action she is able to feel her own presence—for example, by physically punishing her students—she believes words to be like ‘spiders dangling by their mouths from a beam, swinging and twisting and never touching’.

‘That was when I learned that words are no good; that words don’t ever fit even what they are trying to say at. When [my son] was born I knew that motherhood was invented by someone who had to have a word for it because the ones that had the children didn’t care whether there was a word for it or not. I knew that fear was invented by someone that had never had the fear; pride, who never had the pride.’

Words, she expands, are ‘just a shape to fill a lack; that when the right time came, you wouldn’t need a word for that any more than for pride or fear’ or love.

This all should immediately remind us of the views of Wittgenstein, who argued that inner mental states cannot be known; that wouldn’t make sense, for they are incommunicable. There is a divide between mind and world, which is what Addie alludes to.

Nonetheless, in Philosophical Investigations (published posthumously in 1953) Wittgenstein writes that meaning can be conveyed, practically, if the rules of a public language game are followed, for language is a social practice.

Does this mean we shouldn’t try to bridge said gap? Here we can draw on Stanley Cavell’s distinction between (1) knowledge and (2) acknowledgement: (1) there is a limited capacity of language to capture truths about the world and others’ experiences; (2) however, through sympathy we can acknowledge in others what we cannot experience ourselves. Too stark a divide unduly abolishes our obligations to the world and that which we value.

Indeed, Addie is able to gain acknowledgement by forcing pain in others—her husband; her students—not by using words but by exacting revenge and violence. Of the students, she says:

‘I would look forward to the times when they faulted, so I could whip them. When the switch fell I could feel it upon my flesh […] and I would think with each blow of the switch: Now you are aware of me! Now I am something in your secret and selfish life.’

Addie is sceptical of language’s faithfulness to worlds privately and uniquely inhabited. But she seeks acknowledgement. Her daughter, Dewey Dell, unlike her mother, fears even acknowledgement: the obtaining of worldly connections is a violation of her aloneness. Of the recognisable changes to her body during an unwanted pregnancy, she says: ‘The process of coming unalone is terrible’.

The Bundrens are isolated farmers who live in simple fashion. Their thoughts are incoherent and stream-like. Faulkner and Wittgenstein both show that the private worlds from which we feel and sense are inaccessible to language. This limit is felt particularly strongly by the Bundrens, alienated countryfolk whose linguistic capacities and abilities to follow language games are already impoverished.

⁂

Words are signifiers. Your name, for example, signifies you, the signified. But perhaps saying is a cheap substitute for doing. Addie Bundren thought so.

‘Sometimes I would lie by him [my husband, Anse] in the dark, hearing the land that was now of my blood and flesh, and I would think: Anse. Why Anse? Why are you Anse. I would think about his name until after a while I could see the word as a shape, a vessel, and I would watch him liquefy and flow into it like cold molasses flowing out of the darkness into the vessel, until the jar stood full and motionless: a significant shape profoundly without life like an empty door frame; and then I would find that I had forgotten the name of the jar […]

‘I would think how words go straight up in a thin line, quick and harmless, and how terrible doing goes along the earth, clinging to it.’

Post link

Our top 5 articles of 2021

As we approach the birth of 2022, we take stock of fading 2021—its many happenings; those could-have-beens; the lost and the gained.

At this time of reflection—in limbo between Christmas and the New Year—we reveal our most-popular articles of the year.

Pictured in order, they are:

1)‘The Philosophy of Infidelity’byJames Clark Ross

3)‘Scepticism and Anxiety’ by George Williams

4)‘The Philosophy of Moon’byJames Clark Ross

5)‘Reality, and the Intelligible Reality’ by Keigo Shimada

This list is just for 2021. Here you can see our most-read articles ever.

Have a great end to the year.

Post link

Merry Christmas

(Pictured at the top of the tree: the much-disputed comma.)

To: Everyone

We wish you a very merry Christmas. Have a great break. We love you. We will see you soon.

From:The Human Front

Post link

Buddhist Psychedelics

TodayThe Human Front revisits Buddhism.

Dylan Ngan compares meditative practice dhyāna to experiences with psychedelic drugs. Do the similarities run deep?

Read more here.

Post link

The personal identity of bodies

- ‘She’s not your mum anymore!’ In Shaun of the Dead (2004) Shaun (Simon Pegg) must decide whether to shoot and kill his own mother—or, rather, the zombie occupying her body. Shaun initially acts like the person is his mother by virtue of the body; he attaches her to it. But he reverses his position, thus accepting that his mother died when her body was zombified and lost her mind.

- InThe Lion King (1994) eventually Simba reaches a fork in the road: he must choose between his past life, rooted in family legacy, or his newfound independence. Will his choice define him?

- InFuturamaS5E8 Fry faces a similar dilemma to Simba’s: year 2000 or year 3000?

- InTotal Recall (1990) Douglas Quaid (Arnold Schwarzenegger) wrestles with the contents of his memory to determine whether he is a miner or a secret agent. Memory and reality are blurred over the course of the story. We are encourage to distrust psychological criteria of identity less, particularly those premised on memory.

- InWestworldDolores, as a transplanted consciousness, is able to occupy different bodies to take revenge on humans—something which defines her life, given her past enslavement. Will it ever be possible to construct a being whose identity is transferrable like this? Or is the body too important for identity?

- InBlack MirrorS2E2 we watch on as a bewildered woman, who has had her memories wiped, be hounded by members of the public for a prior crime she obviously doesn’t remember. Can there be justice without memory?

In virtue of whatare you the person who lacked control of their bowel movements and who cried for cuddles with Mummy? This is an important question—well, sort of.

Politics, law, love, friendship—they all assume singular, persisting entities. But upon what basis are you an entity and how do you persist?

Here are two conflicting options: the self either has a psychological or a biological status. One person can’t have both. Previously, we ran through John Locke’s argument that a person goes where their consciousness goes. Now let’s consider the importance of the body.

A thought experiment

If Locke is right, it is theoretically possible to ‘download’ a person and ‘upload’ them into another body. To quote Marya Schechtman (2005): ‘Why should it matter to us that the memory experiences in question be in one substance rather than another if it does not change the character of consciousness?’

But one philosopher, by the name of Bernard Williams, created a thought experiment which undermines this position. Imagine you are about to switch from body A to body B(a stranger goes in the reverse direction). You are told that, afterwards, one of you will receive $100,000; the other will be tortured. Now answer this: would you rather be AorB? Rationally, B is the answer.

However, Williams asserts your fear of torture won’t be shaken off, for you identify with your body, expressing fear qua being ‘in’ that body—a fear which isn’t subdued by your thoughts.

Imagine further you’ll be tortured tomorrow but your memories will be wiped before the torture takes place. You shouldn’t be terrified—psychologically, the person won’t be you since your mental states won’t be retained—but you are scared, right?

Therefore, psychological accounts fail to strip minds from bodies. We are concerned for our bodies regardless of our psychological states. So body-switching cases don’t work.

Owning one’s body

To this effect, dying philosophy teacher Gretchen Weirob argued to a friend that even if there is somebody exactly similar to her in another body, it could never be her. Only this body—‘overweight, injured, and lying in bed’—could house her. There might be a Gretchen copy somewhere, indiscernible to others, but that Gretchen won’t possess the original identity.

How about you: can you imagine ever being anchored to another body?

⁂

We take strong ownership over psychological aspects of our lives, too. Numerous works of fiction explore personal identity in accessible yet exciting ways, asking us to consider the extent to which we are defined by our bodily or mental properties. We feature six above.

⁂

Hallucinogenic drugs apparently break up the unified structures of an embodied self. Is the self really that flimsy a concept?

Post link

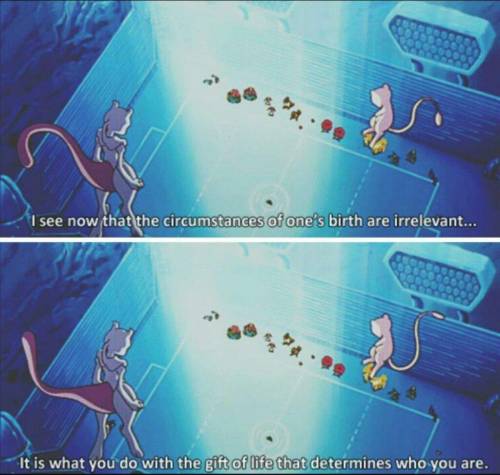

The personal identity of clones

This week we focus on personal identity. And today we discuss the sameness of clones.

Let’s go.

Personal identity

PhilosopherJohn Locke argued that a person goes where their consciousness goes; their personhood consists in things like memories. Therefore, a person must be able to extend their consciousness backwards to past events to be the person presently who experienced them.

Some absurdities arise, however. Why trust memories to solidly define us? I might have a genuine belief that I am Ash Ketchum but, alas, I am not ☹ And what if I was asleep or drunk, beyond memory collection: was I really not there? Still, there is something interesting going on here, for where a person is apparently situated is in their consciousness.

In one of Locke’s examples a prince, via his consciousness, is able to enter a cobbler’s body. He takes his ‘princely thoughts’ with him.

Clones

Let’s apply Locke’s view to clones by asking: if a person is cloned, are there two of the same person?

No. Locke would have denied this claim. One’s point of consciousness can move between bodies but ‘the soul’ cannot be in more than one place at once.

This is bad news for a clone: the original soul stays with the host. The clone may faithfully recollect past events and share personality traits. They can live indistinguishably in ignorance. But their life can be deflated with one prick of the truth, with which they will realise that their life is a lie: that there is no organic connection to their memories; that they did not experience those events.

These are truly gutting thoughts to consider. But there is hope in life anew—that is, if we follow Mewtwo in Pokémon: The First Movie(1998):

‘I see now that the circumstances of one’s birth are irrelevant; it is what you do with the gift of life that determines who you are.’

Cloning imprisons a copy of the soul. However, a unique vantage point is created from which a clone becomes increasingly autonomous. They gather new experiences, forging new memories. Their soul is new. They are original. Their life belongs to them.

Nice one, Mewtwo.

⁂

Some afterthoughts are due.

What is it to be somebody connected through time? After all, our cells die and are recycled, our personalities change, and our memories falter. On what grounds do we persist?

For Locke, bodies are less important for personal identity than psychological states (cf. bodily vs. psychological criteria). Sidestepping accounts of bodily criteria, Lockeans think our identities are born in memories and other features of psychology. Schechtman (2005) argues that self-narratives and elements of unconsciousness play a part too.

In memory we are often misguided. Memories alone, as objects of thought, are residuals of imperfectly recorded events—events which occur infinitesimally in the present and are forever being replaced. Our connections to those memories are loose. They are flimsy. The memories lose their vivaciousness over time.

But perhaps beneath memory we are still made. To quote Ralph Waldo Emerson:

‘I cannot remember the books I’ve read any more than the meals I have eaten; even so, they have made me.’

Post link

‘Ten Questions with Ben Springett’

‘Enjoying that moment between wakefulness and the obliteration of sleep where rationality has almost entirely slipped away but I can just about realise that I am about to fall asleep.’

(Pictured: Jean Lecomte du Nouÿ’s A Eunuch’s Dream[1874].)

‘Ten Questions’ is a new feature on The Human Front where we ask academic philosophers the same ten questions. 'Interviewing philosophers in this way gives us access to, dare I say it, the people inside the academics!’

Ben Springett is a philosophy of dreaming specialist who we interviewed last year. We went to revisit him for another fascinating interview—this time armed with our new tool, Ten Questions.

Read more here.

Post link

‘Cat, the bravest animal and most prone to sleep, does not deny sleeping as such: she wills it, she even seeks it out, provided she is shown a bag for it.’ — Flea-bag Meat-stew, On the Genealogy of Paws

Post link

![Faulkner and Wittgenstein on the privacy of experience(Pictured: Addie Bundren [Beth Grant] in James Faulkner and Wittgenstein on the privacy of experience(Pictured: Addie Bundren [Beth Grant] in James](https://64.media.tumblr.com/a3e77e51df6a393b3d6f1dfcef07faae/e6d137e19008395e-56/s500x750/c0371d7d5d4345963ffbdc5b607e7e7dfced4659.jpg)