#social ontology

The elements of Mills’ “black radical liberalism”

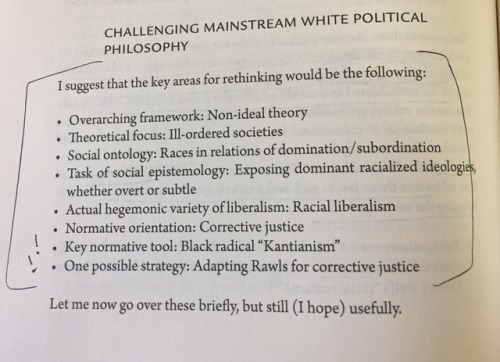

Charles W. Mills, Black Rights/White Wrongs: The Critique of Racial Liberalism (2017), 206

Post link

Being natural

We often speak about things being ‘natural’ or ‘more natural’ than other things. But what does this claim amount to? What does it mean to be natural?

Natural kinds

The concept of natural kind may be of service to us.

Something is of a natural kind if it can be grouped according to the structure of the natural world. The natural world can be ‘carved at the joints’ (Plato). Good theories, then, cut nature along these joints. Physics, for example, has it that electrons (meat) belong to the natural kind of fundamental particles.

Not so fast

However, human beings have blurred the boundaries of naturalness; for our actions and nature are in a constant interplay. At what point should something be considered artificial or arbitrary instead of natural?

Given our inquisitive and creative ways, we have used technology to synthesise vitamin C and new chemical elements (e.g., einsteinium [Es]). We have created ideal conditions for viruses (e.g., COVID-19) to spread globally—a virus which mutates via us. And while plants (e.g., GMO foods) can be grown from natural resources and share biological attributes with ‘wild’ flora, we have manipulated their DNA.

Are none of these examples natural in your eyes?

Philosophy to the rescue?

It’s tempting to think that only mind-independent things, entirely free of human involvement, are natural. But this approach eliminates a lot. Perhaps some metaphysics and philosophy of science can help us tighten up the definition.

For David Lewis there are ‘perfectly natural’ properties, like those described in physics and laws of nature; they are fundamental, simple, and intrinsic. But less-than-perfectly-natural things also exhibit degrees of naturalness; they are just more complex and abundant.

A more-liberal conception of naturalness is available in the work of Quine, whose natural kinds merely share natural properties. The scope of these natural kinds, however, is liable to becoming enormous. For example, if liquid is a natural kind, we haven’t exactly carved nature at the joints; a huge number of items fit this description.

Of course, philosophy didn’t rescue us.

⁂

A helpful concept here is social construction.

Humanscausally construct things (e.g., money) which are real but whose existences aren’t inevitable; for they are contingent on human decision-making. They are not natural but social kinds.

But we also constitutively construct things. These are things which necessarily stand in relations to human features and activity.

Take black and woman as two potential human kinds. Are they autonomously real, are they socially constructed, or are they both? While each is said to instantiate its own collection of biological properties, parts of their realities seem to depend on aspects of human culture, such as oppression and privilege, as well as causal factors, such as geography and gender norms.

(Pictured: What of nature survives the influence of ‘man’? [Francesco Paggiaro/Pexels])

Post link

Ontological pluralism

Harry Potter exists. He just exists in a different way to you; and the degree to which he exists is lesser than the degree to which you exist—or so the ontological pluralist might say.

Isn’t this absurd? Let’s take a step back and ask what we mean by ‘exist’. This is an important question of ontology which has massive ramifications for how we see the world. For perhaps existence has different strands.

Restriction

I’ll go first: something exists if it is real, that is, a feature of reality. But this circularity doesn’t clear up anything at all. What counts as real?

Most people feel comfortable in saying material things are real. Tables and electrons exist because they are physical. Fine. But what about everything else? We don’t want to unnecessarily restrict the domain.

Do numbers exist? What about the property of being red, the love of a couple, one’s gender, a shadow, and an instance of depression? Will you deny their existences because none is construed as physical? The lines are more blurred than you first thought.

Race

Consider the importance of these questions through the following example in social ontology.

Does race exist? Some claim that it doesn’t: that there is no scientific basis for dividing us by it. However, one potential consequence of this claim is that discrimination of racial groups isn’t real. For if we aren’t distinguished in race, who exactly is being discriminated?

By raising the bar of existence too high we cannot properly assert discrimination. But will we really deny discrimination’s existence simply because, biologically, the features of human individuals vary according to a sliding scale and not according to distinct racial groups?

A contrario, discrimination is formed in our minds and is present in our language and our decision-making: in how we talk to each other, in implicit bias, in governments spending less on housing and education and hospitals in certain areas, and so forth. History clearly tells us that certain groups of people are discriminated more than others.

To turn the problem on its head: race is real precisely because we perceive the differences between people in our minds.

Degrees of being

Contemporary metaphysician Kris McDaniel offers a compelling account of ontological pluralism in 2017’s The Fragmentation of Being, authorising different ‘modes’ of being. When invoked in language these modes are more restricted than the generic concept of existence and ‘analogous’ to each other (a concept borrowed from medieval philosophy). To quote Aristotle, ‘Being is said in many ways.’

That there are multiple modes of existence has a long history as an idea in philosophy. Aquinas didn’t believe that God and creatures exist in the same way and said mind-dependent objects are merely ‘beings of reason’. Similarly, Leibniz discerned the absolute existence of monads from the attenuated existence of everything else. Meinong defined two modes of real objects: concreta (e.g. physical objects) and subsistence (e.g. timeless facts about physical objects). Heidegger identified ways of being in Existenz (of creatures), subsistence (of abstract objects), readiness-to-hand (of equipment), and presentness-at-hand (of matter). Gilbert Ryle claimed ontological pluralism is motivated by the idea that it is ridiculous to claim that ‘exist’ is deployable for radically different things, such as God and the number two. You get the point.

Like his peer Ted Sider, McDaniel claims there are different ‘quantifiers’ for asserting existence with (philosophical jargon). These capture fictional characters as real abstract objects (with whatever our best theory is, according to Peter van Inwagen,à laQuine).Things in the past exist, too; so do other worlds and holes. They are all simply impoverished in their being. They are ‘beings-by-courtesy’.

If you still reckon this doctrine is too wild, think about existence as follows. Existence is like mass: an elephant and an ant each has mass but the former is more massive. Likewise, in some way, Harry Potter exists; he’s just not as real as you.

(Image credit: Brian Selznick/Scholastic.)

Post link