#leibniz

Beyond the Enlightenment Rationalists:

From imaginary to probable numbers - V

(continued from here)

The four Cartesian quadrants provide the two-dimensional analogue of the number line and its graphic representation in Cartesian coordinate space. This is the true native habitat of the square and, by implication, of square root. Because Enlightenment mathematicians found fit to define square root in a different context inadvertently -that of the number line- we will find it necessary to devise a different name for what ought rightly to have been called square root, but wasn’t. I propose that we retain the existent definition of tradition and refer to the new relationship between opposite numbers in the square, that is to say, opposite vertices through two dimensions or antipodal numbers, as contra-square root.[1]

Modified from image found here.

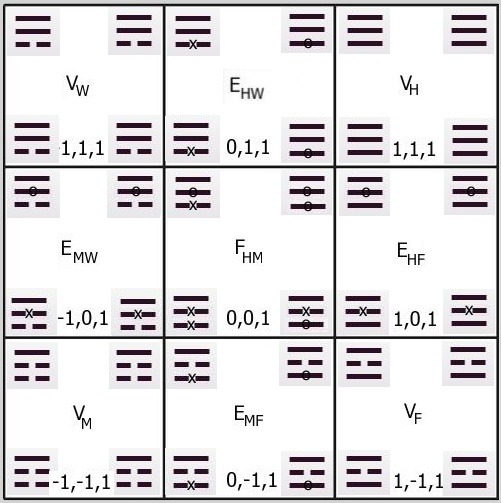

Given this fresh context - one of greater dimension than the number line - it soon becomes clear with little effort that a unit number[2]ofany dimension multiplied by itself gives as result the identity element of that express dimension. For the native two-dimensional context of the square the identity element is OLD YANG, the bigram composed of two stacked yang (+) Lines, which corresponds to yang (+1), the identity element in the one-dimensional context of the number line. In a three-dimensional context, the identity element is the trigram HEAVEN which is composed of three stacked yang (+) Lines. The crucial idea here is that the identity element differs for each dimensional context, and whatever that context might be, it produces no change when in the operation of multiplication it acts as operator on any operand within the stated dimension.[3]

As a corollary it can be stated that any number in any dimension n composed of any combination of yang Lines (+1) and yin Lines (-1) if multiplied by itself (i.e., squared) produces the identity element for that dimension. In concrete terms this means, for example, that any bigram multiplied by itself equals the bigram OLD YANG; any of eight trigrams multiplied by itself equals the trigram HEAVEN; and any of the sixty-four hexagrams multiplied by itself equals the hexagram HEAVEN; etc. (valid for any and all dimensions without exception). Consequently, the number of roots the identity element has in any dimension n is equal to the number 2n, these all being real roots in that particular dimension.

Similar contextual analysis would show that the inversion element of any dimension n has 2n roots of the kind we have agreed to refer to as contra-square roots in deference to the Mathematics Establishment.[4]

That leads us to the possibly startling conclusion that in every dimension n there is an inversion element that has the same number of roots as the identity elementandall of them are real roots. For two dimensions the two pairs that satisfy the requirement are bigram pairs

For one dimension there is only a single pair that satisfies. That is (surprise, surprise) yin(-1)/yang (+1). What it comes down to is

this:

If we are going to continue to insist on referring to square root

in terms of the one-dimensional number line, then

- +1 has two real roots of the traditional variety, +1 and -1

- -1 has two real roots of the newly defined contra variety,

+1/-1 and -1/+1

So where do imaginary numbers and quaternions fit in all this? The short answer is they don’t. Imaginary numbers entered the annals of human thought through error. There was a pivotal moment[5] in the history of mathematics and science, an opportunity to see that there are in every dimension two different kinds of roots - - - what has been called square root and what we are calling contra-square roots. Enlightenment mathematicians and philosophers essentially allowed the opportunity to slip through their fingers unnoticed.[6]

Descartes at least saw through the veil. He called the whole matter of imaginary numbers ‘preposterous’. It seems his venerable opinion was overruled though. Isaac Newton had his say in the matter too. He claimed that roots of imaginary numbers “had to occur in pairs.” And yet another great mathematician, philosopher opined. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, in 1702 characterized √−1 as “that amphibian between being and non-being which we call the imaginary root of negative unity.” Had he but preserved such augury conspicuously in mind he might have elaborated the concept of probable numbers in the 18th century. If only he had truly understood the I Ching, instead of dismissing it as a primitive articulation of his own binary number system.

(continuedhere)

Image: The four quadrants of the Cartesian plane. By convention the quadrants are numbered in a counterclockwise direction. It is as though two number lines were placed together, one going left-right, and the other going up-down to provide context for the two-dimensional plane. Sourced from Math Is Fun.

Notes

[1] My preference might be for square root to be redefined from the bottom up, but I don’t see that happening in our lifetimes. Then too this way could be better.

[2] By the term unit number, I intend any number of a given dimension that consists entirely of variant elements of the number one (1) in either its positive or negative manifestation. Stated differently, these are vectors having various different directions within the dimension, but all of scalar value -1 (yin) or +1 (yang). All emblems of I Ching symbolic logic satisfy this requirement. These include the Line, bigram, trigram, tetragram, and hexagram. In any dimension n there exist 2n such emblems. In sum, for our purposes here, a unit number is any of the set of numbers, within any dimension n, which when self-multiplied (squared) produces the multiplicative identity of that dimension which is itself, of course, a member of the set.

ADDENDUM (01 MAY 2016): I’ve since learned that mathematics has a much simpler way of describing this. It calls all these unit vectors. Simple, yes?

[3] I think it fair to presume that this might well have physical correlates in terms of quantum mechanical states or numbers. Here’s a thought: why would it be necessary that all subatomic particles exist in the same dimension at all times given that they have a playing field of multiple dimensions, - some of them near certainly beyond the three with which we are familiar? And why would it not be possible for two different particles to be stable and unchanging in their different dimensions, yet become reactive and interact with one another when both enter the same dimension or same amplitude of dimension?

[4] Since in any contra-pair (antipodal opposites) of any dimension, either member of the pair must be regarded once as operator and once as operand. So for the two-dimensional square, for example, there are two antipodal pairs (diagonals) and either vertex of each can be either operator or operand. So in this case, 2 x 2 = 4. For trigrams there are four antipodal pairs, and 2 x 4 = 8. For hexagrams there are thirty-two antipodal pairs and 2 x 32 = 64. In general, for any dimension n there are 2 x 2n/2 = 2n antipodal pairs or contra-roots.

[5] Actually lasting several centuries, from about the 16th to the 19th century. Long enough, assuredly, for the error to have been discovered and corrected. Instead, the 20th century dawned with error still in place, and physicists eager to explain the newly discovered bewildering quantum phenomena compounded the error by latching onto √−1 and quaternions to assuage their confusion and discomfiture. This probably took place in the early days of quantum mechanics when the Bohr model of the atom still featured electrons as traveling in circular orbits around the nucleus or soon thereafter, visions of minuscule solar systems still fresh in the mind. At that time rotations detailed by imaginary numbers and quaternions may have still made some sense. Such are the vagaries of history.

[6] I think an important point to consider is that imaginary and complex numbers were, -to mathematicians and physicists alike,- new toys of a sort that enabled them to accomplish certain things they could not otherwise. They were basically tools of empowerment which allowed manipulation of numbers and points on a graph more easily or conveniently. They provided

their controllers a longed for power over symbols, if not over the real world itself. In the modern world ever more of what we humans do and want to do involves manipulation of symbols. Herein, I think, lies the rationale for our continued fascination with and dependence on these tools of the trade. They don’t need to actually apply to the world of nature, the noumenal world, so long as they satisfy human desire for domination over the world of symbols it has created for itself and in which it increasingly dwells, to a considerable degree apart from the natural world’s sometimes seemingly too harsh laws.

© 2016 Martin Hauser

Please note: The content and/or format of this post may not be in finalized form. Reblog as a TEXT post will contain this caveat alerting readers to refer to the current version in the source blog. A LINK post will itself do the same. :)

Scroll to bottom for links to Previous / Next pages (if existent). This blog builds on what came before so the best way to follow it is chronologically. Tumblr doesn’t make that easy to do. Since the most recent page is reckoned as Page 1 the number of the actual Page 1 continually changes as new posts are added. To determine the number currently needed to locate Page 1 go to the most recent post which is here. The current total number of pages in the blog will be found at the bottom. The true Page 1 can be reached by changing the web address mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com to mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com/page/x, exchanging my current page number for x and entering. To find a different true page(p) subtract p from x+1 to get the number(n) to use. Place n in the URL instead of x (mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com/page/n) where

n = x + 1 - p. :)

-Page 310-

Bootstrapping Neo-Boolean - I

(continued from here)

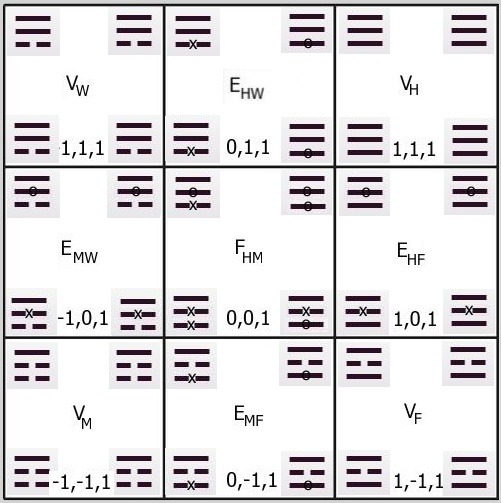

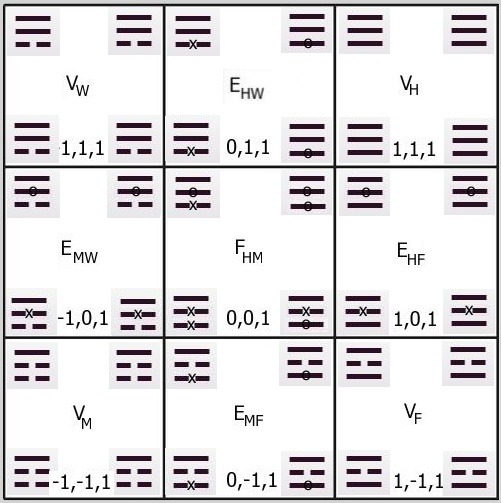

So yes. This is very much a work in progress. And we have strayed now as it happens into unfamiliar territory. Terra incognita. Therewill be dragons.[1] Dragons are errors. Errors are dangerous, and we must slay them. But all in good time. First, we should scout out the terrain. That would be prudent.

Descartes in constructing his system of coordinates built upon the bedrockofelementary algebra and the number line. We’vepreviously called attention to the important but mostly overlooked issue of the 1:1 congruence between number and geometric/spatial position he incorporated implicitly in the logic of his coordinates and questioned the validity of such correspondence, at least with respect to subatomic scales.

Working two centuries later but very much under the influence of Descartes’ thought, George Boole introduced his own unique brand of algebra. A second major influence on the development of his symbolic logic was the binary number system of Leibniz, himself influenced to a large degree by Descartes. We need to carefully follow and connect the dots here. Great advances in human cognition rarely, if ever, occur in isolation and seclusion. There is a fine line to tread though. If progress requires the shoulders of giants to stand on, it is still difficult at times not to be overly influenced by those who came before.

Boole’s new logic, constructed in the wake of what by his time were firmly entrenched systematizations of thought by two of the most highly regarded philosopher mathematicians, was devised in such a manner as to conform to both of these conventions of system design. Significant to our purposes here are the facts that first, Boolean logic echoes Cartesian convention of attributing to each and every location in geometric space a single unique number, and second, it adheres to Leibniz’s convention of using a modulo-2 number system based on binary elements 1 and 0.[2]

The symbolic logic systems of mandalic geometry and the I Ching do not abide by either of these conventions. Instead they are based on what is best described as composite dimensions with four unique truth values (or vector directions) each, ranging from -1 through two distinctive zeros (0a; 0b) to +1, and assignment of numbers to spatial locations through all dimensions by means of probability distributions in place of a simple and simplistic 1:1 distribution. To accommodate these alternative conceptual concepts, we will need to expand and modify traditional Boolean logic as we have already done as regards Cartesian coordinate theory.

For starters here we should doubtless add, the mandalic form is the probability distribution through all dimensions, and the probability distributions are the mandalas. And movement through either or both can only be accomplished by discretized stepwise maneuvers between different amplitudes of dimension separated by obscure quantum leaps of endless being and becoming and being and unbecoming, toward and away from the centers and subcenters of holistic systems, the parts of which are always aiming towards some kind of equilibrium never quite within reach. Which then makes error also a necessary aspect of reality and not simply the fearful monster we imagined. It is error that makes achievement possible.[3][4]

(continuedhere)

Image:Here Be Dragons Map. Detail of he Carta marina (Latin “map of the sea” or “sea map”), drawn by Olaus Magnus in 1527-39. This is the earliest map of the Nordic countries that gives details and place names, by Olaus Magnus [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. The map was in production for 12 years. The first copies were printed in 1539 in Venice. [Wikipedia]

Notes

[1] Mapmakers during the Age of Exploration sometimes placed the phrase “here be dragons” at the edges of their known world, presumably to warn of the dangers lying in wait for sailing vessels and travelers by land who strayed too far from well-traveled routes. Here is a list of all known historical maps on which these words appear.

[2] Or in Boole’s case, we might say, attributing to each proposition in concept space a single truth value: TRUE or FALSE (var YES or NO; or, in electronics applications, ON or OFF.) What we have here, I believe, is in many instances a false dilemma or the old Aristotelian dichotomy of either/or. Quantum physics demands and deserves better. OK, true enough, Boole gets around to extending possibilities by means of multi-term propositions, which his system can readily handle. The question here, though, is whether nature can or does handle such similarly. I think not. I think it approaches the question at a more fundamental level of reasoning and reality: at the most basic level of spacetime itself.

[3] This echoes the view of cybernetics, a transdisciplinary approach for exploring regulatory systems, their structures, constraints, and possibilities.

Cybernetics is relevant to the study of systems, such as mechanical, physical, biological, cognitive, and social systems. Cybernetics is applicable when a system being analyzed incorporates a closed signaling loop; that is, where action by the system generates some change in its environment and that change is reflected in that system in some manner (feedback) that triggers a system change, originally referred to as a “circular causal” relationship. [Wikipedia]

[4] This entire blog and its predecessor are in some sense the chronology of a journey from the familiar shoreline into largely uncharted waters. Hesitant at first, increasingly more daring as time has gone on and I’ve come to see errors to be stepping stones along the way. And there have beenmanyerrors along the way. Some I am not yet cognizant of. But of those I am aware, I have left most intact in spite of since being superseded by ideas superior, more correct or better formulated. I’ve done this because I think it important to map the course of a conceptual journey, how the ideas evolved from A to B to C to D. It also allows readers to participate, to a degree, in the thrill of an exciting adventure of mind, should they so choose. Happy travels.

© 2016 Martin Hauser

Please note: The content and/or format of this post may not be in finalized form. Reblog as a TEXT post will contain this caveat alerting readers to refer to the current version in the source blog. A LINK post will itself do the same. :)

Scroll to bottom for links to Previous / Next pages (if existent). This blog builds on what came before so the best way to follow it is chronologically. Tumblr doesn’t make that easy to do. Since the most recent page is reckoned as Page 1 the number of the actual Page 1 continually changes as new posts are added. To determine the number currently needed to locate Page 1 go to the most recent post which is here. The current total number of pages in the blog will be found at the bottom. The true Page 1 can be reached by changing the web address mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com to mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com/page/x, exchanging my current page number for x and entering. To find a different true page(p) subtract p from x+1 to get the number(n) to use. Place n in the URL instead of x (mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com/page/n) where

n = x + 1 - p. :)

-Page 303-

Beyond Taoism - Part 4

A Vector-based Probabilistic

Number System

Introduction

(continued from here)

Leibniz erred in concluding the hexagrams of the I Ching were based on a number system related to his own binary number system. He had a brilliant mind but was just as fallible as the rest of us. He interpreted the I Ching in terms of his own thought forms, and he saw the hexagrams as a foreshadowing of his own binary arithmetic.[1]

So in considering the hexagram Receptive, Leibniz understood the number 0; in the hexagram Return, the number 1; in the hexagram Army, the number 2; in the hexagram Approach, the number 3; in the hexagram Modesty, the number 4; in the hexagram Darkening of the Light, the number 5; and so on, up to the hexagram Creative, in which he saw the number 63.[2] His error is perhaps excusable in light of the fact that the Taoists, though much closer to the origin of the I Ching in time, themselves misinterpreted the number system it was based on.[3]

From our Western perspectiveI Ching hexagrams are composed of trigrams, tetragrams, bigrams, and ultimately yinandyang Lines. From the native perspective of the I Ching this order of arrangement is putting the cart before the horse. Dimensions and their interactions are, in the view of I Ching philosophy and mandalic geometry, antecedent logically and materially to any cognitive parts we may abstract from them. Taoism in certain contexts has abstracted the parts and caused them to appear as if primary. It has the right to do so if creating its own philosophy, but not as interpretation of the logic of the I Ching. It is a fallacy if so intended.[4]

The Taoists borrowed from the I Ching two-dimensional numbers, treated them as one-dimensional and based their quasi-modular number system on the dimension-deficient result. This is the way they arrived at their seasonal cycle consisting of bigrams: old yin (Winter), young yang (Spring), old yang (Summer), young yin (Autumn), old yin (Winter), and so forth. This represents a very much impoverished and impaired version of the original configuration in the primal strata of the I Ching.[5]

The number system of the I Ching is not a linear one-dimensional number system like the positional decimal number system of the West; nor is it like the positional binary number system invented by Leibniz. It is not even like the quasi-modular number system of Taoism. The key to the number system of the hexagrams is located not in the 64 unchanging explicit hexagrams, but rather in the changing implicit hexagrams found only in the divination practice associated with the I Ching. These number 4032.[6] The manner in which these operate, however, is actually fairly simple and is uniform throughout the system. So once understood, they can be safely relegated to the implicit background, coming into play only during procedures involving divination or in attempts to understand the system fully, logically and materially. When dealing with more ordinary circumstances just the 64 more stable hexagrams need be attended to in a direct and explicit manner.

The Taoist sequence of bigrams is in fact a corruption of the far richer asequential multidimensional arrangement of bigrams that occurs in I Ching hexagrams and divination. There we see that change can occur from any one of the four stable bigrams to any other. If this is so then no single sequence can do justice to the total number possible. The ordering of bigrams presented by Taoism is just one of many that make up the real worlds of nature and humankind. Taoism imparts special significance to this sequence; the primal I Ching does not. It views all possible pathways of change as equally likely.[7]

Next time around we will look further into the implications of this equipotentiality and see how it plays out in regard to the number system of the I Ching.

Section FH(n)[8]

(continuedhere)

Notes

[1] By equating yang with 1 and yin with 0 it is possibletosequence the 64 I Ching hexagrams according to binary numbers 0 through 63. The mere fact that this is possible does not, however, mean that this was intended at the time the hexagrams were originally formulated. Unfortunately, this arrangement of hexagrams seems to have been the only one of which Leibniz had knowledge. This sequence was, in fact, the creation of the Chinese philosopher Shao Yong (1011–1077). It did not exist in human mentation prior to the 11th century CE.

This arrangement was set down by the Song dynasty philosopher Shao Yong (1011–1077 CE), six

centuries before Wilhelm Leibniz described binary notation. Leibniz published ‘De progressione

dyadica’ in 1679. In 1701 the Jesuit Joachim Bouvet wrote to him enclosing a copy of Shao Yong’s 'Xiantian cixu’ (Before Heaven sequence). [Source]

Note also that the author of Calling crane in the shade, the source quoted above, calls attention to confusion that exists about whether the “true binary sequence of hexagrams” should begin with the lowest line as the least significant bit (LSB) or the highest line. He points out that the Fuxi sequence as transmitted by Shao Yong in both circular and square diagrams takes the highest line as the LSB, although in fact it would make more sense in consideration of how the hexagram form is interpreted to take the lowest line as the LSB. My thinking is that either Shao Yong misinterpreted the usage of hexagram form or, more likely, the conventional interpretation of the Shao Yong diagrams is incorrect. Here I have chosen to use the lowest line of the hexagram as the LSB, and I think it possible Leibniz may have done the same.

If one considers the circular Shao Yong diagram, the easier of the two to follow, one can reconstruct the binary sequence, with the lowest line as LSB, by beginning with the hexagram EARTH at the center lower right half of the circle, reading all hexagrams from outside line (bottom) to inside line (top), progressing counterclockwise to MOUNTAIN over WIND at top center, then jumping to hexagram MOUNTAIN over EARTH bottom center of left half of the circle, and progressing clockwise to hexagram HEAVEN at top center. Of the two, this is the interpretation that makes the more sense to me and the one I have followed here, despite the fact that it is not the received traditional interpretation of the Shao Yong sequence. Historical transmissions have not infrequently erred. Admittedly it is difficult to decipher all Lines of some of the hexagrams in the copy Leibniz received due to passage of time and its effects on paper and ink. Time is not kind to ink and paper, nor for that matter to flesh and products of intellect.

In the final analysis, which of the two described interpretations is the better is moot because neither conforms to the logic of the I Ching which is not binary to begin with. Moreover, there is a third interpretation of the Shao Yong sequence that is superior to either described here. It is not binary-based. And why should it be? After all the Fuxi trigram sequence which Shao Yong took as model for his hexagram sequence is itself not binary-based. Perhaps we’ll consider that interpretation somewhere down the road. For now, the main take-away is that Leibniz, in his biased interpretation of the I Ching hexagrams made one huge mistake. Ironically, had he not some 22 years prior already invented binary arithmetic, this error likely would have led him to invent it. It was “in the cards” as they say. At least in certain probable worlds.

[2]ReceptiveandCreative are alternative names for the hexagrams EarthandHeaven, respectively. The sequence detailed can be continued ad infinitum using yin-yang notation, though of course this takes us beyond the realm of hexagrams into what would be, for mandalic geometry and logistics of the I Ching, domains of dimensions numbering more than six. Keep in mind here though that Leibniz was not thinking in terms of dimension but an alternative method of expressing the prevalent base 10 positional number system notation of the West. He held in his grasp the key to unlocking an even greater treasure but apparently never once saw that was so. This seems strange considering his broadly diversified interests and pursuits in the fields of mathematics, physics, symbolic logic, information science, combinatorics, and in the nature of space. Moreover, his concern with these was not just as separate subjects of investigation. He envisaged uniting all of them in a universal language capable of expressing mathematical, scientific, and metaphysical concepts.

[3] Earlier in this blog I have too often confused Taoism with pre-Taoism. The earliest strata of the I Ching belong to an age that preceded Taoism by centuries, if not millennia. Though Taoism was largely based on the philosophy and logic of the I Ching, it didn’t always interpret source materials correctly, or possibly at times it intentionally used source materials in new ways largely foreign to the originals. The number system of the I Ching is a case in point.

In the interest of full disclosure, I am not an expert in the history or philosophy of Taoism. Taoist philosophies are diverse and extensive. No one has a complete set or grasp of all the thoughts, practices and techniques of Taoism. The two core Taoist texts, the Tao Te ChingandChuang-tzu, provide the philosophical basis of Taoism which derives from the eight trigrams (bagua) of Fu Xi, c. 2700 BCE, the various combinations of which created the 64 hexagrams documented in the I Ching. The Daozang, also referred to as the Taoist canon, consists of around 1,400 texts that were collected c. 400, long after the two classic texts mentioned. What I describe as Taoist thought then is abstracted in some manner from a huge compilation, parts of which may well differ from what is presented here. Similar effects of time and history can be discerned in Buddhism, Christianity, Islam and secular schools of thought like Platonism,Aristotelianism,Humanism, etc.

[4] Recent advances in the sciences have begun to raise new ideas regarding the structure of reality. Many of these have parallels in Eastern thought. There has been a shift away from the reductionist view in which things are explained by breaking them down then looking at their component parts, towards a more holistic view. Quantum physics notably has changed the way reality is viewed. There are no certainties at a quantum level, and the experimenter is necessarily part of the experiment. In this new view of nature everything is linked and man is himself one of the linkages.

[5] It is not so much that this is incorrect as that it isextremelylimiting with respect to the capacities of the I Ching hexagrams. A special case has here been turned into a generalization that purports to cover all bases. This may serve well enough within the confines of Taoism but it comes nowhere near elaborating the number system native to the I Ching. We would be generous in describing it as a watered down version of a far more complex whole. Through the centuries both Confucianism and Taoism restructured the I Ching to make it conducive to their own purposes. They edited it and revised it repeatedly, generating commentary after commentary, which were admixed with the original, so that the I Ching as we have it today, the I Ching of tradition, is a hodgepodge of many convictions and many opinions. This makes the quest for the original features of the I Ching somewhat akin to an archaeological dig. I find it not all that surprising that the oracular methodology of consulting the I Ching holds possibly greater promise in this endeavor than the written text. The early oral traditions were preserved better, I think, by the uneducated masses who used the I Ching as their tool for divination than by philosophers and scholars who, in their writings, played too often a game of one-upmanship with the original.

[6] A Line can be either yin or yang, changing or unchanging. Then there are four possible Line types and six Lines to a hexagram. This gives a total of 4096 changing and unchanging hexagrams (46 = 4096). Since there are 64 unchanging hexagrams (26 = 64) there must be 4032 changing hexagrams (4096-64 = 4032).

[7] This calls to mind the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics which was developed in its complete form by Richard Feynman in 1948. See, for example, this description of the path integral formulation in context of the double-slit experiment, the quintessential experiment of quantum mechanics.

[8] This is the closest frontal section to the viewer through the 3-dimensional cube using Taoist notation. See here for further explanation. Keep in mind this graph barely hints at the complexity of relationships found in the 6-dimensional hypercube which has in total 4096 distinct changing and unchanging hexagrams in contrast to the 16 changing and unchanging trigrams we see here. Though this model may be simple by comparison, it will nevertheless serve us well as a key to deciphering the number system on which I Ching logic is based as well as the structure and context of the geometric line that can be derived by application of reductionist thought to the associated mandalic coordinate system of the I Ching hexagrams. We will refer back to this figure for that purpose in the near future.

© 2016 Martin Hauser

Please note: The content and/or format of this post may not be in finalized form. Reblog as a TEXT post will contain this caveat alerting readers to refer to the current version in the source blog. A LINK post will itself do the same. :)

Scroll to bottom for links to Previous / Next pages (if existent). This blog builds on what came before so the best way to follow it is chronologically. Tumblr doesn’t make that easy to do. Since the most recent page is reckoned as Page 1 the number of the actual Page 1 continually changes as new posts are added. To determine the number currently needed to locate Page 1 go to the most recent post which is here. The current total number of pages in the blog will be found at the bottom. The true Page 1 can be reached by changing the web address mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com to mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com/page/x, exchanging my current page number for x and entering. To find a different true page(p) subtract p from x+1 to get the number(n) to use. Place n in the URL instead of x (mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com/page/n) where

n = x + 1 - p. :)

-Page 299-

Beyond Taoism - Part 2

Number System of the I Ching

(continued from here)

Many different number systems exist in the world today. Others have existed in times past. The number system we are most familiar with is base 10 or radix 10, which makes use of ten digits, numbered 0 to 9. Beyond the number 9, the numbers recapitulate, beginning again with 0 and shifting a new “1” to the 10s position, in a positional number system. Using this conventional technique all integers and decimals can be easily and uniquely expressed. This familiar numeral system is also known as the decimal system.[1]

Another number system we are familiar with and use every day is the modular numeral system, particularly in its manisfestation of modulo 12, better known as clock arithmetic. This is a system of arithmetic in which integers “wrap around” and begin again upon reaching a set value, called the modulus. For clock arithmetic, the modulus used is 12. On the typical 12-hour clock, the day is divided into two equal periods of 12 hours each. The 24 hour / day cycle starts at 12 midnight (often indicated as 12 a.m.), runs through 12 noon (often indicated as 12 p.m.), and continues to the midnight at the end of the day. The numbers used are 1 through 11 and 12 (the modulus, acting as zero). Military time is similar, only is based on a 24-hour clock with modulus-24 rather than modulus-12. The modulus-24 system is the most commonly used time notation in the world today.

Binary arithmetic is similar to clock arithmetic, but is modulo-2 instead of modulo-12. The only integers used in this system are 0 and 1, with the “wrap around” back to zero occurring each time the number 1 is reached. Computers, in particular, handle this arithmetic system, which we owe to Leibniz, with remarkable acumen. George Boole also based his true/false logic on binary arithmetic. This, in itself, accounts for some of its strange, counterintuitive aspects, like the fact that in Boolean algebra the sum of 1 + 1 equals 0. Not your father’s arithmetic. But both Leibniz and Boole found profound uses for it. As did the entire digital revolution.

When we come to consideration of the number system and arithmetic used in the I Ching we can anticipate encountering equal difficulty in comprehension, possibly more. The system employed is a modular one - sort of. However, it uses negative 1 (yin) as well as positive 1 (yang) whereas zero (0) is nowhere to be seen, at least not in guise of an explicit dedicated symbol earmarked for the purpose. The "wrap around" appears to occur at both -1 (yin) and +1 (yang). Something different and quite extraordinary is going on here. This is no simple modular numeral system, though it may be masquerading as one.

Thus far the number system of the I Ching sounds much like that of Taoism. It is not, though. We have some big surprises in store for us.

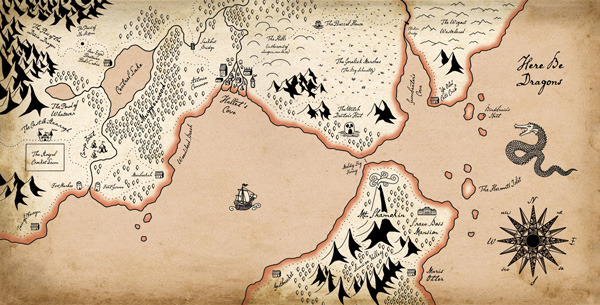

Section FH(n)[2]

(continuedhere)

Notes

[1] See here for a list/description of numeral systems having other bases. A more comprehensive list of numeral systems can be found here.

[2] For explanation of this diagram see here.

© 2015 Martin Hauser

Please note: The content and/or format of this post may not be in finalized form. Reblog as a TEXT post will contain this caveat alerting readers to refer to the current version in the source blog. A LINK post will itself do the same. :)

Scroll to bottom for links to Previous / Next pages (if existent). This blog builds on what came before so the best way to follow it is chronologically. Tumblr doesn’t make that easy to do. Since the most recent page is reckoned as Page 1 the number of the actual Page 1 continually changes as new posts are added. To determine the number currently needed to locate Page 1 go to the most recent post which is here. The current total number of pages in the blog will be found at the bottom. The true Page 1 can be reached by changing the web address mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com to mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com/page/x, exchanging my current page number for x and entering. To find a different true page(p) subtract p from x+1 to get the number(n) to use. Place n in the URL instead of x (mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com/page/n) where

n = x + 1 - p. :)

-Page 297-

Beyond Boole - Part 1

Symbolic Logic for the 21st Century

Boolean Algebra:

Fundamental Operations

(continued from here)

Looking back on how we arrived at this stage of reconstruction of Western thought, I see the difficulty arose in attempting to explain the “missing zero” of Taoism. Blame our troubles on Leibniz. It was he who introduced binary numbers to the West, and made the fateful choice of using zero(0) instead of -1 to counter with +1. Leibniz knew full well of the I Ching, but did not understand it well. He missed the point, seeing in it only a resemblance to his own newly devised system of numbers.

By Leibniz’s time negative numbers were firmly entrenched in the European mind. Why did Leibniz ignore them completely? In doing so he blazed a new trail that led eventually to the digital revolution of recent times. It also led to a dead end in the history of Western thought, one the West has not yet come fully face to face with. It will, though. Give it a few more years.[1]

George Boole, the inventor of what we know today as Boolean logic or Boolean algebra, was one of the thinkers who followed in the footsteps of Leibniz, building on the trail he blazed.[2] When he came to devise his truth tables, he also chose zero(0) as the counterpart to one(1). This led to certain resounding successes. And ultimately, to certain failures that introduced yet another layer to the blind spot of Western symbolic logic. Here we are, almost two centuries later,[3] saddled with and hampered by the unfortunate fallout of that eventful decision still.[4]

Most arguments in elementary algebra denote numbers. However, in Boolean algebra, they denote truth values falseandtrue. Convention has decreed these values are represented with the bits (or binary digits), namely 0 and 1. They do not behave like the integers 0 and 1 though, for which 1 + 1 = 2, but are identified with the elements of the two-element field GF(2), that is, integer arithmetic modulo 2, for which 1 + 1 = 0. (1,2) This causes a substantial problem when we attempt correlation of Taoist logic and Boolean logic. As we will soon discover, Taoist logic is a hybrid logic that is based on both vector inversion and arithmetic modulo 2. As such, it ought prove relatable to both Cartesian coordinates and Boolean algebra, though it may necessitate “forcing a larger foot in a smaller glass slipper.”

Taoism chose ages ago to use ‘yin’ and 'yang’ as its logical symbols. Although this appears, at first, to be a binary system, like those of Leibniz and Boole, on closer inspection it proves not to be. It is one of far greater logical complexity, alternatively binary or ternary with intermediate third element understood. This implied third element is able to bestow balance and equilibrium throughout all of the Taoist logical system. This is where the 'missing zero’ of Taoism went. Only it is a very different zero than the 'zero’ of Western thought. It is a zero of infinite potential rather than one of absolute emptiness. It is a zero of continual beginnings and endings, not of finality. It is one of the things that make the I Ching totally unique in the history of human cognition. All these hidden zeros are wormholes between dimensions and between different amplitudes of dimension.

So where does this all lead to, then? We’ve seen that the Taoist 'yin’ can readily be made commensurate with 'minus 1’ of Western arithmetic, the number line, and Cartesian coordinates.[5] But if it is to remain true to Taoist logic, it cannot be made commensurate with the Western 'zero’. We’ve found the Taoist number system and geometry to be Cartesian-like but not Cartesian. Now we discover them to be Boolean-like, not Boolean. Sorry, Leibniz, they are not so much as remotely like your binary system. You were far too quick to disesteem the unique qualities of the I Ching.[6]

This all has far-reaching consequences for Western thought in general. Especially though, for symbolic logic, mathematics, and physics. More specifically for our purposes here it means that when we create our Taoist notation transliteration of Cartesian coordinates, we will need also to translate Boolean logic into terms compatible with Taoist thought, that is to say, from a two-value system based on '1s’ and '0s’ into a three-value system based on '1s’, ’-1s’, and the ever-elusive invisible balancing-act '0s’ of Taoism.[7] We turn to that undertaking next.

(continuedhere)

Image: Fundamental operations of Boolean algebra. Symbolic Logic, Boolean Algebra and the Design of Digital Systems. By the Technical Staff of Computer Control Company, Inc. Other logical operations exist and are found useful by non-engineer logicians. However, these can always be derived from the three shown. These three are most readily implementable by electronic means. The digital engineer, therefore, is usually concerned only with these fundamental operations of conjunction, disjunction, and negation.

Notes

[1] It is at times like this that I am thankful I am not a member of Academia. Were I so, I could not afford, from a practical standpoint, to make claims such as this. Tenure notwithstanding.

[2] A knowledge of the binary number system is an important adjunct to an understanding of the fundamentals of Symbolic Logic.

[3] If we look back far enough in time, it was the introduction of “zero” as a number and a philosophical concept that led us down this tangled garden path, though the history of human thought is nothing if not interesting.

[4] Far out speculative thought here: Were binary numbers and Boolean logic based on +1s and -1s instead of +1s and 0s, might it not be possible to construct today a software-based quantum computer requiring no fancy juxtapositions and superpositions of subatomic particles? Think on it for a while before dismissing the thought as irrational folly.

[5] More correctly expressed, it can be made commensurate with the domain of negative numbers, since it is a vector symbol, properly speaking, concerned only with direction, not magnitude.

[6] Unfortunately there is still little understanding of the true nature of the symbolic logic encoded in the I Ching, as exemplified by this quote:

The I Ching dates from the 9th century BC in China. The binary notation in the

I Ching is used to interpret its quaternary divination technique.

It is based on taoistic duality of yin and yang.Eight trigrams (Bagua) and a set of 64 hexagrams (“sixty-four” gua), analogous to the three-bit and six-bit binary numerals, were in use at least as early as the Zhou Dynasty of ancient China.

The contemporary scholar Shao Yong rearranged the hexagrams in a format that resembles modern binary numbers, although he did not intend his arrangement to be used mathematically. Viewing the least significant bit on top of single hexagrams in Shao Yong’s square and reading along rows either from bottom right to top left with solid lines as 0 and broken lines as 1 or from top left to bottom right with solid lines

as 1 and broken lines as 0 hexagrams can be interpreted as sequence from 0 to 63.

[Wikipedia]

It was this Shao Yong sequence of hexagrams (Before Heaven sequence) that Leibniz viewed six centuries after the Chinese scholar created it, so maybe he can be forgiven his error after all.

The more significant point here might be that an important Neo-Confucian philosopher, cosmologist, poet, and historian of the 11th century either was no longer able to access the original logic and meaning of the I Ching or, at the very least, was hellbent on reinterpreting it in a manner contradictory to its original intent. The latter is a distinct possibility, as Neo-Confucianism was an attempt to create a more rationalist secular form of Confucianism by rejecting superstitious and mystical elements of Taoism and Buddhism that had influenced Confucianism since the Han Dynasty (206 BC–220 AD).

[7] Taoist logic and mandalic geometry share some of the characteristics of both Cartesian coordinates and Boolean logic, but not all of either. Descartes’ system is indeed a ternary one when viewed in terms of vector direction rather than scalar magnitude. That fits with the requirements of Taoist logic. It is, on the other hand, dimension-poor, as Taoist logic and geometry require a full six independent dimensions for execution. Boolean logic lacks the necessary third logical element -1, which causes inversion through a central point of mediation. But we shall see, it does bestow the ability to enter and exit a greater number of dimensional levels by means of its logical gates. Used together in an appropriate manner, these two can provide a key to understanding Taoist logic and geometry. Speculating even further, Taoist thought might provide a key to interpretation of quantum mechanics, the same quantum mechanics devised in the early twentieth century that no one can yet explain. Well, I mean, actually, Taoist thought in the formulation given it by mandalic geometry. Why feign modesty, when this work will likely linger in near-total obscurity for the next hundred years gathering dust or whatever it is that pixels gather in darkness undisturbed.

© 2015 Martin Hauser

Please note: The content and/or format of this post may not be in finalized form. Reblog as a TEXT post will contain this caveat alerting readers to refer to the current version in the source blog. A LINK post will itself do the same. :)

Scroll to bottom for links to Previous / Next pages (if existent). This blog builds on what came before so the best way to follow it is chronologically. Tumblr doesn’t make that easy to do. Since the most recent page is reckoned as Page 1 the number of the actual Page 1 continually changes as new posts are added. To determine the number currently needed to locate Page 1 go to the most recent post which is here. The current total number of pages in the blog will be found at the bottom. The true Page 1 can be reached by changing the web address mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com to mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com/page/x, exchanging my current page number for x and entering. To find a different true page(p) subtract p from x+1 to get the number(n) to use. Place n in the URL instead of x (mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com/page/n) where

n = x + 1 - p. :)

-Page 294-

Besides, there are hundreds of indications leading us to conclude that at every moment there is in us an infinity of perceptions, unaccompanied by awareness or reflection; that is, of alterations in the soul itself, of which we are unaware because these impressions are either too ·minute and too numerous, or else too unvarying, so that they are not sufficiently distinctive on their own. But when they are combined with others they do nevertheless have their effect and make themselves felt, at least confusedly, within the whole. This is how we become so accustomed to the motion of a mill or a waterfall, after living beside it for a while, that we pay no heed to it. Not that this motion ceases to strike on our sense-organs, or that something corresponding to it does not still occur in the soul because of the harmony between the soul and the body; but these impressions in the soul and the body, lacking the appeal of novelty, are not forceful enough to attract our attention and our memory, which are applied only to more compelling objects. Memory is needed for attention: when we are not alerted, so to speak, to pay heed to certain of our own present perceptions, we allow them to slip by unconsidered and even unnoticed. But if someone alerts us to them straight away, and makes us take note, for instance, of some noise which we have just heard, then we remember it and are aware of just having had some sense of it. Thus, we were not straight away aware of these perceptions, and we became aware of them only because we were alerted to them after an interval, however brief. To give a clearer idea of these minute perceptions which we are unable to pick out from the crowd, I like to use the example of the roaring noise of the sea which impresses itself on us when we are standing on the shore. To hear this noise as we do, we must hear the parts which make up this whole, that is the noise of each wave, although each of these little noises makes itself known only when combined confusedly with all the others, and would not be noticed if the wave which made it were by itself. We must be affected slightly by the motion of this wave, and have some perception of each of these noises, however faint they may be; otherwise there would be no perception of a hundred thousand waves, since a hundred thousand nothings cannot make something. Moreover, we never sleep so soundly that we do not have some feeble and confused ·sensation; and the loudest noise in the world would never waken us if we did not have some perception of its start, which is small, just as the strongest force in the world would never break a rope unless the least force strained it and stretched it slightly, even though that little lengthening which is produced is imperceptible. These minute perceptions, then, are more effective in their results than has been recognized. They constitute that je ne sais quoi, those flavours, those images of sensible qualities, vivid in the aggregate but confused as to the parts; those impressions which are made on us by the bodies around us and which involve the infinite; that connection that each being has with all the rest of the universe. It can even be said that by virtue of these minute perceptions the present is big with the future and burdened with the past, that all things harmonize - sympnoia panta, as Hippocrates put it - and that eyes as piercing as God’s could read in the lowliest substance the universe’s whole sequence of events - ‘What is, what was, and what will soon be brought in by the future’ [Virgil].

– Leibniz, New Essays on Human Understanding, “Preface”

And in consequence, all bodies feel the effects of everything that happens in the universe. Accordingly, someone who sees all could read in each all that happens throughout, and even what has happened or will happen, observing in the present that which is remote, be it in time or in place. Sympnoia panta, all things conspire, as Hippocrates said. But a soul can read in itself only that which is represented distinctly there; it cannot unfold all-at-once all of its complications, because they extend to infinity.

– Leibniz, Monadology #61

God in the quad // Ronald knox

Pietro Della Vecchia (Italian, 1603-1678), Portrait of Erhard Weigel, 1649. Oil on canvas, 92.5 x 80.5. Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk

“Erhard Weigel (1625 – 1699) was a German mathematician, astronomer and philosopher. From 1653 until his death he was professor of mathematics at Jena University. He was the teacher of Leibniz (1663) and other notable students.” [en.wikipedia]

Post link

Bootstrapping Neo-Boolean - I

(continued from here)

So yes. This is very much a work in progress. And we have strayed now as it happens into unfamiliar territory. Terra incognita. Therewill be dragons.[1] Dragons are errors. Errors are dangerous, and we must slay them. But all in good time. First, we should scout out the terrain. That would be prudent.

Descartes in constructing his system of coordinates built upon the bedrockofelementary algebra and the number line. We’vepreviously called attention to the important but mostly overlooked issue of the 1:1 congruence between number and geometric/spatial position he incorporated implicitly in the logic of his coordinates and questioned the validity of such correspondence, at least with respect to subatomic scales.

Working two centuries later but very much under the influence of Descartes’ thought, George Boole introduced his own unique brand of algebra. A second major influence on the development of his symbolic logic was the binary number system of Leibniz, himself influenced to a large degree by Descartes. We need to carefully follow and connect the dots here. Great advances in human cognition rarely, if ever, occur in isolation and seclusion. There is a fine line to tread though. If progress requires the shoulders of giants to stand on, it is still difficult at times not to be overly influenced by those who came before.

Boole’s new logic, constructed in the wake of what by his time were firmly entrenched systematizations of thought by two of the most highly regarded philosopher mathematicians, was devised in such a manner as to conform to both of these conventions of system design. Significant to our purposes here are the facts that first, Boolean logic echoes Cartesian convention of attributing to each and every location in geometric space a single unique number, and second, it adheres to Leibniz’s convention of using a modulo-2 number system based on binary elements 1 and 0.[2]

The symbolic logic systems of mandalic geometry and the I Ching do not abide by either of these conventions. Instead they are based on what is best described as composite dimensions with four unique truth values (or vector directions) each, ranging from -1 through two distinctive zeros (0a; 0b) to +1, and assignment of numbers to spatial locations through all dimensions by means of probability distributions in place of a simple and simplistic 1:1 distribution. To accommodate these alternative conceptual concepts, we will need to expand and modify traditional Boolean logic as we have already done as regards Cartesian coordinate theory.

For starters here we should doubtless add, the mandalic form is the probability distribution through all dimensions, and the probability distributions are the mandalas. And movement through either or both can only be accomplished by discretized stepwise maneuvers between different amplitudes of dimension separated by obscure quantum leaps of endless being and becoming and being and unbecoming, toward and away from the centers and subcenters of holistic systems, the parts of which are always aiming towards some kind of equilibrium never quite within reach. Which then makes error also a necessary aspect of reality and not simply the fearful monster we imagined. It is error that makes achievement possible.[3][4]

(continuedhere)

Image:Here Be Dragons Map. Detail of he Carta marina (Latin “map of the sea” or “sea map”), drawn by Olaus Magnus in 1527-39. This is the earliest map of the Nordic countries that gives details and place names, by Olaus Magnus [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons. The map was in production for 12 years. The first copies were printed in 1539 in Venice. [Wikipedia]

Notes

[1] Mapmakers during the Age of Exploration sometimes placed the phrase “here be dragons” at the edges of their known world, presumably to warn of the dangers lying in wait for sailing vessels and travelers by land who strayed too far from well-traveled routes. Here is a list of all known historical maps on which these words appear.

[2] Or in Boole’s case, we might say, attributing to each proposition in concept space a single truth value: TRUE or FALSE (var YES or NO; or, in electronics applications, ON or OFF.) What we have here, I believe, is in many instances a false dilemma or the old Aristotelian dichotomy of either/or. Quantum physics demands and deserves better. OK, true enough, Boole gets around to extending possibilities by means of multi-term propositions, which his system can readily handle. The question here, though, is whether nature can or does handle such similarly. I think not. I think it approaches the question at a more fundamental level of reasoning and reality: at the most basic level of spacetime itself.

[3] This echoes the view of cybernetics, a transdisciplinary approach for exploring regulatory systems, their structures, constraints, and possibilities.

Cybernetics is relevant to the study of systems, such as mechanical, physical, biological, cognitive, and social systems. Cybernetics is applicable when a system being analyzed incorporates a closed signaling loop; that is, where action by the system generates some change in its environment and that change is reflected in that system in some manner (feedback) that triggers a system change, originally referred to as a “circular causal” relationship. [Wikipedia]

[4] This entire blog and its predecessor are in some sense the chronology of a journey from the familiar shoreline into largely uncharted waters. Hesitant at first, increasingly more daring as time has gone on and I’ve come to see errors to be stepping stones along the way. And there have beenmanyerrors along the way. Some I am not yet cognizant of. But of those I am aware, I have left most intact in spite of since being superseded by ideas superior, more correct or better formulated. I’ve done this because I think it important to map the course of a conceptual journey, how the ideas evolved from A to B to C to D. It also allows readers to participate, to a degree, in the thrill of an exciting adventure of mind, should they so choose. Happy travels.

© 2016 Martin Hauser

Please note: The content and/or format of this post may not be in finalized form. Reblog as a TEXT post will contain this caveat alerting readers to refer to the current version in the source blog. A LINK post will itself do the same. :)

Scroll to bottom for links to Previous / Next pages (if existent). This blog builds on what came before so the best way to follow it is chronologically. Tumblr doesn’t make that easy to do. Since the most recent page is reckoned as Page 1 the number of the actual Page 1 continually changes as new posts are added. To determine the number currently needed to locate Page 1 go to the most recent post which is here. The current total number of pages in the blog will be found at the bottom. The true Page 1 can be reached by changing the web address mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com to mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com/page/x, exchanging my current page number for x and entering. To find a different true page(p) subtract p from x+1 to get the number(n) to use. Place n in the URL instead of x (mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com/page/n) where

n = x + 1 - p. :)

-Page 303-

Beyond Taoism - Part 4

A Vector-based Probabilistic

Number System

Introduction

(continued from here)

Leibniz erred in concluding the hexagrams of the I Ching were based on a number system related to his own binary number system. He had a brilliant mind but was just as fallible as the rest of us. He interpreted the I Ching in terms of his own thought forms, and he saw the hexagrams as a foreshadowing of his own binary arithmetic.[1]

So in considering the hexagram Receptive, Leibniz understood the number 0; in the hexagram Return, the number 1; in the hexagram Army, the number 2; in the hexagram Approach, the number 3; in the hexagram Modesty, the number 4; in the hexagram Darkening of the Light, the number 5; and so on, up to the hexagram Creative, in which he saw the number 63.[2] His error is perhaps excusable in light of the fact that the Taoists, though much closer to the origin of the I Ching in time, themselves misinterpreted the number system it was based on.[3]

From our Western perspectiveI Ching hexagrams are composed of trigrams, tetragrams, bigrams, and ultimately yinandyang Lines. From the native perspective of the I Ching this order of arrangement is putting the cart before the horse. Dimensions and their interactions are, in the view of I Ching philosophy and mandalic geometry, antecedent logically and materially to any cognitive parts we may abstract from them. Taoism in certain contexts has abstracted the parts and caused them to appear as if primary. It has the right to do so if creating its own philosophy, but not as interpretation of the logic of the I Ching. It is a fallacy if so intended.[4]

The Taoists borrowed from the I Ching two-dimensional numbers, treated them as one-dimensional and based their quasi-modular number system on the dimension-deficient result. This is the way they arrived at their seasonal cycle consisting of bigrams: old yin (Winter), young yang (Spring), old yang (Summer), young yin (Autumn), old yin (Winter), and so forth. This represents a very much impoverished and impaired version of the original configuration in the primal strata of the I Ching.[5]

The number system of the I Ching is not a linear one-dimensional number system like the positional decimal number system of the West; nor is it like the positional binary number system invented by Leibniz. It is not even like the quasi-modular number system of Taoism. The key to the number system of the hexagrams is located not in the 64 unchanging explicit hexagrams, but rather in the changing implicit hexagrams found only in the divination practice associated with the I Ching. These number 4032.[6] The manner in which these operate, however, is actually fairly simple and is uniform throughout the system. So once understood, they can be safely relegated to the implicit background, coming into play only during procedures involving divination or in attempts to understand the system fully, logically and materially. When dealing with more ordinary circumstances just the 64 more stable hexagrams need be attended to in a direct and explicit manner.

The Taoist sequence of bigrams is in fact a corruption of the far richer asequential multidimensional arrangement of bigrams that occurs in I Ching hexagrams and divination. There we see that change can occur from any one of the four stable bigrams to any other. If this is so then no single sequence can do justice to the total number possible. The ordering of bigrams presented by Taoism is just one of many that make up the real worlds of nature and humankind. Taoism imparts special significance to this sequence; the primal I Ching does not. It views all possible pathways of change as equally likely.[7]

Next time around we will look further into the implications of this equipotentiality and see how it plays out in regard to the number system of the I Ching.

Section FH(n)[8]

(continuedhere)

Notes

[1] By equating yang with 1 and yin with 0 it is possibletosequence the 64 I Ching hexagrams according to binary numbers 0 through 63. The mere fact that this is possible does not, however, mean that this was intended at the time the hexagrams were originally formulated. Unfortunately, this arrangement of hexagrams seems to have been the only one of which Leibniz had knowledge. This sequence was, in fact, the creation of the Chinese philosopher Shao Yong (1011–1077). It did not exist in human mentation prior to the 11th century CE.

This arrangement was set down by the Song dynasty philosopher Shao Yong (1011–1077 CE), six

centuries before Wilhelm Leibniz described binary notation. Leibniz published ‘De progressione

dyadica’ in 1679. In 1701 the Jesuit Joachim Bouvet wrote to him enclosing a copy of Shao Yong’s 'Xiantian cixu’ (Before Heaven sequence). [Source]

Note also that the author of Calling crane in the shade, the source quoted above, calls attention to confusion that exists about whether the “true binary sequence of hexagrams” should begin with the lowest line as the least significant bit (LSB) or the highest line. He points out that the Fuxi sequence as transmitted by Shao Yong in both circular and square diagrams takes the highest line as the LSB, although in fact it would make more sense in consideration of how the hexagram form is interpreted to take the lowest line as the LSB. My thinking is that either Shao Yong misinterpreted the usage of hexagram form or, more likely, the conventional interpretation of the Shao Yong diagrams is incorrect. Here I have chosen to use the lowest line of the hexagram as the LSB, and I think it possible Leibniz may have done the same.

If one considers the circular Shao Yong diagram, the easier of the two to follow, one can reconstruct the binary sequence, with the lowest line as LSB, by beginning with the hexagram EARTH at the center lower right half of the circle, reading all hexagrams from outside line (bottom) to inside line (top), progressing counterclockwise to MOUNTAIN over WIND at top center, then jumping to hexagram MOUNTAIN over EARTH bottom center of left half of the circle, and progressing clockwise to hexagram HEAVEN at top center. Of the two, this is the interpretation that makes the more sense to me and the one I have followed here, despite the fact that it is not the received traditional interpretation of the Shao Yong sequence. Historical transmissions have not infrequently erred. Admittedly it is difficult to decipher all Lines of some of the hexagrams in the copy Leibniz received due to passage of time and its effects on paper and ink. Time is not kind to ink and paper, nor for that matter to flesh and products of intellect.

In the final analysis, which of the two described interpretations is the better is moot because neither conforms to the logic of the I Ching which is not binary to begin with. Moreover, there is a third interpretation of the Shao Yong sequence that is superior to either described here. It is not binary-based. And why should it be? After all the Fuxi trigram sequence which Shao Yong took as model for his hexagram sequence is itself not binary-based. Perhaps we’ll consider that interpretation somewhere down the road. For now, the main take-away is that Leibniz, in his biased interpretation of the I Ching hexagrams made one huge mistake. Ironically, had he not some 22 years prior already invented binary arithmetic, this error likely would have led him to invent it. It was “in the cards” as they say. At least in certain probable worlds.

[2]ReceptiveandCreative are alternative names for the hexagrams EarthandHeaven, respectively. The sequence detailed can be continued ad infinitum using yin-yang notation, though of course this takes us beyond the realm of hexagrams into what would be, for mandalic geometry and logistics of the I Ching, domains of dimensions numbering more than six. Keep in mind here though that Leibniz was not thinking in terms of dimension but an alternative method of expressing the prevalent base 10 positional number system notation of the West. He held in his grasp the key to unlocking an even greater treasure but apparently never once saw that was so. This seems strange considering his broadly diversified interests and pursuits in the fields of mathematics, physics, symbolic logic, information science, combinatorics, and in the nature of space. Moreover, his concern with these was not just as separate subjects of investigation. He envisaged uniting all of them in a universal language capable of expressing mathematical, scientific, and metaphysical concepts.

[3] Earlier in this blog I have too often confused Taoism with pre-Taoism. The earliest strata of the I Ching belong to an age that preceded Taoism by centuries, if not millennia. Though Taoism was largely based on the philosophy and logic of the I Ching, it didn’t always interpret source materials correctly, or possibly at times it intentionally used source materials in new ways largely foreign to the originals. The number system of the I Ching is a case in point.

In the interest of full disclosure, I am not an expert in the history or philosophy of Taoism. Taoist philosophies are diverse and extensive. No one has a complete set or grasp of all the thoughts, practices and techniques of Taoism. The two core Taoist texts, the Tao Te ChingandChuang-tzu, provide the philosophical basis of Taoism which derives from the eight trigrams (bagua) of Fu Xi, c. 2700 BCE, the various combinations of which created the 64 hexagrams documented in the I Ching. The Daozang, also referred to as the Taoist canon, consists of around 1,400 texts that were collected c. 400, long after the two classic texts mentioned. What I describe as Taoist thought then is abstracted in some manner from a huge compilation, parts of which may well differ from what is presented here. Similar effects of time and history can be discerned in Buddhism, Christianity, Islam and secular schools of thought like Platonism,Aristotelianism,Humanism, etc.

[4] Recent advances in the sciences have begun to raise new ideas regarding the structure of reality. Many of these have parallels in Eastern thought. There has been a shift away from the reductionist view in which things are explained by breaking them down then looking at their component parts, towards a more holistic view. Quantum physics notably has changed the way reality is viewed. There are no certainties at a quantum level, and the experimenter is necessarily part of the experiment. In this new view of nature everything is linked and man is himself one of the linkages.

[5] It is not so much that this is incorrect as that it isextremelylimiting with respect to the capacities of the I Ching hexagrams. A special case has here been turned into a generalization that purports to cover all bases. This may serve well enough within the confines of Taoism but it comes nowhere near elaborating the number system native to the I Ching. We would be generous in describing it as a watered down version of a far more complex whole. Through the centuries both Confucianism and Taoism restructured the I Ching to make it conducive to their own purposes. They edited it and revised it repeatedly, generating commentary after commentary, which were admixed with the original, so that the I Ching as we have it today, the I Ching of tradition, is a hodgepodge of many convictions and many opinions. This makes the quest for the original features of the I Ching somewhat akin to an archaeological dig. I find it not all that surprising that the oracular methodology of consulting the I Ching holds possibly greater promise in this endeavor than the written text. The early oral traditions were preserved better, I think, by the uneducated masses who used the I Ching as their tool for divination than by philosophers and scholars who, in their writings, played too often a game of one-upmanship with the original.

[6] A Line can be either yin or yang, changing or unchanging. Then there are four possible Line types and six Lines to a hexagram. This gives a total of 4096 changing and unchanging hexagrams (46 = 4096). Since there are 64 unchanging hexagrams (26 = 64) there must be 4032 changing hexagrams (4096-64 = 4032).

[7] This calls to mind the path integral formulation of quantum mechanics which was developed in its complete form by Richard Feynman in 1948. See, for example, this description of the path integral formulation in context of the double-slit experiment, the quintessential experiment of quantum mechanics.

[8] This is the closest frontal section to the viewer through the 3-dimensional cube using Taoist notation. See here for further explanation. Keep in mind this graph barely hints at the complexity of relationships found in the 6-dimensional hypercube which has in total 4096 distinct changing and unchanging hexagrams in contrast to the 16 changing and unchanging trigrams we see here. Though this model may be simple by comparison, it will nevertheless serve us well as a key to deciphering the number system on which I Ching logic is based as well as the structure and context of the geometric line that can be derived by application of reductionist thought to the associated mandalic coordinate system of the I Ching hexagrams. We will refer back to this figure for that purpose in the near future.

© 2016 Martin Hauser

Please note: The content and/or format of this post may not be in finalized form. Reblog as a TEXT post will contain this caveat alerting readers to refer to the current version in the source blog. A LINK post will itself do the same. :)

Scroll to bottom for links to Previous / Next pages (if existent). This blog builds on what came before so the best way to follow it is chronologically. Tumblr doesn’t make that easy to do. Since the most recent page is reckoned as Page 1 the number of the actual Page 1 continually changes as new posts are added. To determine the number currently needed to locate Page 1 go to the most recent post which is here. The current total number of pages in the blog will be found at the bottom. The true Page 1 can be reached by changing the web address mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com to mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com/page/x, exchanging my current page number for x and entering. To find a different true page(p) subtract p from x+1 to get the number(n) to use. Place n in the URL instead of x (mandalicgeometry.tumblr.com/page/n) where

n = x + 1 - p. :)

-Page 299-

Ontological pluralism

Harry Potter exists. He just exists in a different way to you; and the degree to which he exists is lesser than the degree to which you exist—or so the ontological pluralist might say.

Isn’t this absurd? Let’s take a step back and ask what we mean by ‘exist’. This is an important question of ontology which has massive ramifications for how we see the world. For perhaps existence has different strands.

Restriction

I’ll go first: something exists if it is real, that is, a feature of reality. But this circularity doesn’t clear up anything at all. What counts as real?

Most people feel comfortable in saying material things are real. Tables and electrons exist because they are physical. Fine. But what about everything else? We don’t want to unnecessarily restrict the domain.

Do numbers exist? What about the property of being red, the love of a couple, one’s gender, a shadow, and an instance of depression? Will you deny their existences because none is construed as physical? The lines are more blurred than you first thought.

Race

Consider the importance of these questions through the following example in social ontology.

Does race exist? Some claim that it doesn’t: that there is no scientific basis for dividing us by it. However, one potential consequence of this claim is that discrimination of racial groups isn’t real. For if we aren’t distinguished in race, who exactly is being discriminated?

By raising the bar of existence too high we cannot properly assert discrimination. But will we really deny discrimination’s existence simply because, biologically, the features of human individuals vary according to a sliding scale and not according to distinct racial groups?

A contrario, discrimination is formed in our minds and is present in our language and our decision-making: in how we talk to each other, in implicit bias, in governments spending less on housing and education and hospitals in certain areas, and so forth. History clearly tells us that certain groups of people are discriminated more than others.

To turn the problem on its head: race is real precisely because we perceive the differences between people in our minds.

Degrees of being

Contemporary metaphysician Kris McDaniel offers a compelling account of ontological pluralism in 2017’s The Fragmentation of Being, authorising different ‘modes’ of being. When invoked in language these modes are more restricted than the generic concept of existence and ‘analogous’ to each other (a concept borrowed from medieval philosophy). To quote Aristotle, ‘Being is said in many ways.’

That there are multiple modes of existence has a long history as an idea in philosophy. Aquinas didn’t believe that God and creatures exist in the same way and said mind-dependent objects are merely ‘beings of reason’. Similarly, Leibniz discerned the absolute existence of monads from the attenuated existence of everything else. Meinong defined two modes of real objects: concreta (e.g. physical objects) and subsistence (e.g. timeless facts about physical objects). Heidegger identified ways of being in Existenz (of creatures), subsistence (of abstract objects), readiness-to-hand (of equipment), and presentness-at-hand (of matter). Gilbert Ryle claimed ontological pluralism is motivated by the idea that it is ridiculous to claim that ‘exist’ is deployable for radically different things, such as God and the number two. You get the point.

Like his peer Ted Sider, McDaniel claims there are different ‘quantifiers’ for asserting existence with (philosophical jargon). These capture fictional characters as real abstract objects (with whatever our best theory is, according to Peter van Inwagen,à laQuine).Things in the past exist, too; so do other worlds and holes. They are all simply impoverished in their being. They are ‘beings-by-courtesy’.

If you still reckon this doctrine is too wild, think about existence as follows. Existence is like mass: an elephant and an ant each has mass but the former is more massive. Likewise, in some way, Harry Potter exists; he’s just not as real as you.

(Image credit: Brian Selznick/Scholastic.)

Post link