#squid game grammar

따라(서)

This form is the combination of the verb 따르다 (to follow) and the simple clause connecting form 아/어(서) which we covered a little while ago. As you may remember, when a word ends in the vowel 으, the following conjugation depends on the preceding vowel. If the preceding vowel is 아, then the 아(서) conjugation is used. For any other preceding vowel, 어(서) is used. Given that 따르다 has the preceding vowel 아, it is conjugated to 따라(서).

This form can be used in a sentence to connect 따르다 to another verb, for example, 따라 가다 (to follow someone who is going somewhere).

에 따라(서)

When 에 is added to this form, the meaning changes. The typical formulation of this form in a sentence is N + 에 따라(서) + A, and it’s used to say that in accordance with N, V happens. Here are some examples of how this may be used:

According to the directions, we should go that way.

길안내에 따라서 우리는 저 쪽으로 가 야 돼요.

People should act in accordance with the culture of a country.

사람들은 그 나라의 문화에 따라 행동을 해 야 돼요.

If we understand 에 따라(서) to mean ‘in accordance with,’ we can then figure out the meaning of the Game Administrator’s statement, 여러분의 뜻에 따라 게임의 중단 여부를 투표하겠습니다. He is saying ‘in accordance with your wishes (뜻에 따라), we will take a vote to decide whether or not the game will end.

We can also understand the Game Administrator’s next statement. He says ‘참가자 한 명당 걸려 있는 상금 액수 1억 따라서 255억의 상금이 돼지 저금통에 적립되었습니다’. The first clause means ‘for every player, the amount of money at stake was 1억,’ and the second means ‘225억 has been collected into the piggy bank’. If 따르다 connects these two clauses, then we can come to the conclusion that the full sentence must translate to ‘Following (the rule) that for every player, the amount of money at stake was 1억, 255억 has been accumulated in the piggy bank’.

게 하다 and 시키다

Some of you may remember that not too long ago, we looked at the verb 시키다, which means ‘to order’ in the sense of ordering food or ordering something online. When used as a grammar form, 시키다 is added onto the verb or adjective stem to indicate that someone is being forced to do that action.

The grammar form 게 하다 which we’ll be looking at today has an identical meaning to 시키다, but also has some further usages. Sometimes, the words can be switched out for each other, although in other circumstances there needs to be a slight alteration to ensure that they’re naturalised into a sentence, given that technically 시키다 is a verb, whereas 게 하다 is solely a grammar form. Let’s take these two sentences:

The teacher made the students study during the afterschool class.

선생님은 삭생들을 방과후 수업 시간 동안 공부시켰어요.

선생님은 삭생들을 방과후 수업 시간 동안 공부하게 했어요.

My mom made me clean my room.

엄마가 나에게 방 청소를 시켰어.

엄마가 날 방 청소하게 했어.

In the first sentence, the two forms are interchangeable, however, since the second form uses a verb which is directed at someone, it uses 에게 in this circumstance. Think of it as ‘my mom made me clean my room’ (게 하다) and ‘my mom said to me that I need to clean my room’ (시키다).

게 하다 and 게 해 주다

Aside from the meaning of making something happen, 게 하다 also carries the meaning of letting something happen. When using this grammar, there is no clear distinction between which meaning is being used, so you need to be aware of context within a situation to determine whether the speaker means ‘make’ or ‘let’. Here are some examples:

My parents won’t let me go outside late at night.

부모님은 제가 밤늦게 못 나가게 하셨어요.

I will let him sleep.

저는 그를 자게 할 거예요.

If the action that is taking place is also beneficial for the person who is being allowed or made to do something, 주다 can be added to the form.

My mom made my dad give up smoking.

엄마가 아빠에게 담배를 끊게 하졌어요.

I let the students study.

저는 학생들을 공부하게 해 주었어요.

This is the usage that is being used in the example by Sang-Woo. By adding 게 하다 to the verb 투표를 하다, he is asking them to let the players vote. There are a number of nuances added to this phrase: 주다 shows that the players would benefit from it, 시 is added for formality, and 죠 indicates that since it’s within the contract that they can vote to leave, the Game Administrator knows that he has to allow it.

A note on the usage of (이)라고

Although we’ve already covered the quoting grammar form in our translation of 식샤를 합시다 2, I want to make a quick note on the usage of it in this scene, as the usage is a little different.

As we’ve already covered, (이)라고 하다 is the noun quoting form, combining 이다 and the regular quoting form 다고 하다. For example:

He said that he was a doctor.

그가 의사라고 했어요.

If you already understand this form, you may still be confused listening to the players in this scene. Player 066 says ‘그럼 당신들도 끝장이라고!’ which technically could translate to ‘I said that you’re done for then!’ however, this player hasn’t mentioned 끝장 (an unfortunate end) or anything similar before this point. How can he be quoting something he hasn’t said?

Here’s the thing, 이라고 can be used when you’re saying something again, but can also be used when you’re trying to strongly express something that was already obvious in your previous statement. Previously, player 066 tells the guards ‘우리 안 풀어 주면 핸드폰 위치 추적이라도 해서 여기로 찾아올 거야!’ (If you don’t let us go, the police will track down this place using the GPS on our phones!). Although he hasn’t specifically stated that they’ll be finished, it’s obvious in what he is saying. Using (이)라고 simply emphasises this last point based on the prior information.

Honestly, in my opinion this usage is a nuisance since it’s a little difficult to use as a non-native speaker. There’s no real equivalent in English so it’s difficult to understand when to use it, and it’s a fairly uncommon grammar form to use too. The best thing to do is just keep this nuance in mind and look out for examples to refresh your memory.

(으)러

(으)러 is the shortened form of (으)려고 하다, which is used to indicate that someone is doing something for the purpose of creating the opportunity for the following action to occur. For example:

I finished my homework quickly so that I could go outside.

밖에 일찍 나가려고 숙제를 빨리 했어요.

I am studying diligently so that I can pass the TOPIK exam.

TOPIK 시험을 합격하려고 열심히 공부하고 있어요.

The shortened form, (으)러, has limited usage. It can only be used to say that someone is going or coming somewhere in order to do something. Typically, this form is used with 가다 or 오다, however, as seen in the above example from Squid Game, it can be used alongside other verbs as long as there is some kind of movement taking place.

I am going to school to study.

공부하러 학교에 가고 있어.

I decided to go to the police to report fraud.

사기를 신고하러 겅찰서에 가기로 했어요.

I want to go and see a movie.

저는 영화를 보러 나가고 싶어요.

Although you can’t substitute (으)러 for (으)려고 하다 in situations where no movement is involved, you can substitute (으)려고 하다 in for (으)러 at any time. For example, the sentence in this scene could be written as ‘경찰들이 여기 실종된 사람들 찾으려고 금방 여길 찾아올걸, 아마?’ and it would still be grammatically correct. Technically, this means that you could go your whole life speaking Korean and never have to use this shorter form, however, it’s still useful to learn so that you can understand others when they use this form.

뿐이다

뿐 is a particle which can be attached to a noun to say ‘just’ or ‘only’. This is very similar to the particle 만, which has the same meaning. There is no real difference between the two, and they can mostly be interchanged, but the sentence must change to accommodate the grammar rules of each particle.

만 can be used in place of the topic or subject marker that would usually follow a noun, and can be used with verbs which are turned into nouns. 뿐 can only be used at the end of a sentence with 이다 attached to it, and can only be used with nouns. This sentence uses a regular noun, and can be changed to use either form:

He only likes movies.

그는 영화만좋아해요.

그가 좋아하는 것은 영화뿐이에요.

This sentence uses the nominalised form, where a verb is changed into a noun. Because of this, there is no way to use 뿐 in this sentence.

If you only go to class, you’ll be able to graduate.

매일 수업에 가기만 하면 졸업할 수 있을 거예요.

뿐만 아니라

With the addition of 아니라, this form negates the singularity created by 뿐 in the sentence. It is used in a sentence with the structure N + 뿐만 아니라 + N(도), and translates to ‘not only N, but N as well’.

Not only did I buy coffee, I also bought snacks.

커피뿐만 아니라 간식도 샀어요.

I didn’t just buy my things, but the things my friend needed too.

내것뿐 아니라 내 친구것도 샀어요

ㄹ/을 뿐

Including the object marker before 뿐 creates a slightly different meaning. Although it is a very small difference in spelling, the nuance is very different. This version carries the meaning that there in nothing special about the thing which 뿐 is describing. This usage essentially minimises what is being said.

I just put a bit of water in it, why are you so mad? It’s only ramen…

불을 조금 넣었다고 화를 이렇게 많이 내? 그냥 라면일 뿐이야…

It’s just a joke.

그것은 농담일 뿐이에요.

Buying this is just a waste of money.

그것을 사는섯은 돈 낭비일 뿐이에요.

This is the form which the Game Administrator is using in this scene. By saying ‘이건 게임일 뿐입니다’ (this is just a game), he is trying to minimise the situation. To both him and the VIPs, the Squid Game is truly just a game for entertainment. The players rightfully object to this, saying ‘사람을 그렇게 죽여 놓고 게임이라고요?’ (people just died like that and you’re saying it’s only a game?!). Obviously, as potential victims of the game, the Administrator’s attempt to minimise the situation is ridiculous.

One final thing to note about this form is that whilst the object particle is used to add this nuance, it is also used with the past tense form of 뿐. This can cause confusion as to whether the original form or the nuanced form is being used. In this case, you will have to use context clues to determine how 뿐 is being used in the situation.

This post is essentially a follow on from the previous post, since in the last scene we looked at, 아/어 놓다 was added onto 시키다 to make 시켜 놓다.

아/어 놓다

The addition of 아/어 놓다 (sometimes shortened to 아/어 놔) to a verb allows you to indicate that the action is completed, and that the object of that sentence is left in the resulting state. Although in some cases, this grammar rule may seem insignificant and frustrating to have to include, in other circumstances, it’s usage is much more obviously important. Take this sentence for example:

To prevent the spread of COVID-19, please open the windows (and leave them open).

COVID-19 전파 방지를 위해 창문을 열어 놓으세요.

This is the kind of message that you may see on a sign in a indoor public area nowadays. Although it could just read 창문을 열다, this leaves room for interpretation. People may think that they can just open the window for 5 minutes and close it, when actually for the sake of public health, they need to be open constantly to help ventilate the space.

The closest thing to this grammar in English is ‘to keep ….’. In this instance, you may say ‘keep the windows open’. However, in English you wouldn’t usually need to indicate that the state of something is maintained after an action, it’s just presumed. This is why it can be difficult for English speakers to understand this grammar rule, and why it can be so frustrating for us to use, since we don’t see the need for it. Here are some more examples to highlight the less obvious usages of 아/어 놓다:

A: I sent you a text earlier, didn’t you get it?

B: I was in class. I didn’t see it because I turn off my phone when I’m in class (and keep it turned off).

A: 아까 문자 보냈는데 못 받으셨어요.

B: 수업 중이었어요. 수업 중에는 휴대폰을 꺼 놓거든요.

Since it’s hot, I’ll go to the meeting room early to turn on the air con (and keep it on so that the room isn’t too hot)

날씨가 더우니까 제가 회의실에 미리 가서 에어컨을 틀어 놓을게요.

Seulgi prepared dinner (it was left prepared to eat later).

슬기가 저녁을 다 준비해 놓았어요.

In the scene in Squid Game, player 119 states ‘애들 놀이를 시켜 놓고 사람을 죽이는 게’. As we learned from last time, ‘애들 놀이를 시기다’ means ‘to make them play children’s games’. The addition of 아/어 놓다 adds to the indication that they are still in the state of playing the games, but I find it interesting that it also highlights the danger of this situation. They are finished with the first game, and people have died, but the remaining players still have to continue through the games.

시키다

The verb 시키다 can be used to mean ‘order’ in the sense of ordering food or ordering something online, however it also has the double meaning of ordering someone to do something when it’s used as a grammatical form. When used as a grammar form, 시키다 is added onto the verb or adjective stem to indicate that someone is being forced to do that action.

Some common usages of 시키다 include:

❥이해시키다 - to make (someone) understand

❥연슴시키다 - to make (someone) practise

❥실망시키다 - to make (someone) disappointed / to disappoint someone

❥상기시키다 - to make (someone) recall / to remind someone

The teacher made the students study during the afterschool class.

선생님은 삭생들을 방과후 수업 시간 동안 공부시켰어요.

The fact that I am unemployed disappointed my mother.

제가 실업자라는 것이 저의 어머니를 실망시켰어요.

I worked hard so I satisfied my boss.

저는 열심히 일해서 부장님을 만족시켰어요.

Plain Form vs 시키다

Sometimes, due to translation errors, the meaning given to the plain form of a verb may make it seem as if 시키다 isn’t needed. For example, 감동하다 is often translated to ‘to impress someone’. You may then think that you can just use the standard 하다 form because the meaning already implies that you are making someone impressed. This is not the case, however, and there is no word which would negate 시키다 and make it useless. But then, how are they different?

Naver translates 감동하다 to ‘to be impressed’. In this instance, the action is happening to the speaker, changing the meaning from the above translation. Therefore, to say that you are making someone impressed, you can use 감동시키다 to essentially flip the verb and make it so that you are the one impressing someone else. Here are some examples:

I listened to my mother’s words and was very impressed.

저는 엄마의 말을 듣고 아주 감동했어요.

I made my mother impressed because I worked hard all day.

저는 하루 종일 열심히 일해서 엄마를 감동시켰어요.

Form Variations

Some other common variations of this form include:

❥ Verb root + 를/을 시키다

❥ Verb root + 하게 시키다

❥ Verb + (으)라고 시키다

In the examples from the scene, the speaker uses the first variation. This has no different meaning to the original form of 시키다, but is just another way to say the same thing.

All of these particles can be used to show that something is being done or given to someone. The difference between these three particles is:

❥ 에게 is used mainly in written communication or formal situations (although it may also be used conversationally sometimes).

❥ 한테 is used mainly in conversation.

❥ 께 is used when talking to or about someone who requires respect (eg. elder/teacher/boss).

These particles come after the recipient, rather than before as they do in English. Here are some examples of their usage:

I gave a present to my friend yesterday.

어제 친구에게 선물을 줬어요.

I send a birthday card to my friend every year.

저는 매년 언니에게 생일 카드를 보냅니다.

My friend gives a watch to their boyfriend.

동생이 남친한테 시계를 줘요.

I want to ask (to) my friend.

저는 친구한테 물어보고 싶어요.

I call (to) my grandma.

할머니께 전화 드려요.

I will give this book to my teacher.

이 잭이 선생님께 드릴 거예요.

Something that is important to note with this grammar is that although it means ‘to’, it can also be used to mean ‘from’. Obviously, this can be confusing, and it can be difficult for learners to figure out how to use this in conversation. When listening to others, however, you can understand which meaning is intended by the context. By listening to native speakers, it becomes easier to understand and use this grammar.

By analysing the Game Administrator’s words, we can grasp which version he is intending to use. He begins with 다시 말씀드리지만 (let me explain again), then states 여러분에게 기회를 드리는 겁니다 or 여러분에게(to you)기회를(an opportunity)드리는(to give) 것입니다(this is). By context, we can understand that he is using the ‘to’ usage. He is saying to the players ‘we are giving you an opportunity’ or ‘this is an opportunity’ with an emphasis on the charitable aspect. Here, 에게 is being used instead of 한테 to indicate the formality of the situation, even though it is being used in spoken conversation.

In this scene, I find that the translation is a little off. ‘Let me remind you’ comes off as passive aggressive and indicates a kind of hostility towards the players which I feel isn’t present in the Korean version. The Game Administrator is still using honorifics, and although his tone is always cold, he actually speaks very politely towards the players. I feel like this would have been translated better as ‘please understand, we are giving you an opportunity’, as this carries the same tone as the Korean version, although it strays slightly from the exact meaning.

는 것

In Korean, when describing a noun with a verb, you always use the core structure V+는 N. For example:

A student who studies.

공부하는 학생.

A flower which blooms.

피는 꽃.

A woman who walks.

걷는 여자.

Describing a noun with a verb allows you to then use this more detailed noun in a sentence, where you can add on a verb, adjective, or end it in 이다.

Students who study frequently get good grades, right?

자주공부하는 학생들이 좋은 성적을 얻죠.

The flower which blooms hugely is pretty.

크게피는 꽃이예뻐.

The girl who walks fast is young.

빨리걷는 여자는어려요.

는 게

The name of the grammatical principle used above is 는 것, with 것 meaning ‘thing’. Any noun can be substituted in for 것, as shown in the examples above. However, if using the basic form, 것, there is an additional rule which is important to learn. When 것 is used with the subject marker 이, this can be shortened to 게. Because of this, you may see 는 게 used alongside phrases such as 좋다, 싫다, and 아니다.

This is how 는 게 is used in this scene. The whole clause ‘여러분을 해치거나 돈을 받아 내려는 게 / To hurt you or take your money to pay your debts’ is made into a noun with 는 것이 so that 아니다 can be added in order to negate the whole clause. Again, the translation is accurate here, with the only thing missing being the nuance of respect that the Game Administrator is talking to the players with.

는 게 아니라

Using 는 게 아니라 between two clauses allows you to negate the first clause and instead propose the second clause as the truth. You may sometimes see this as 는 것 아니라, but the shortened version 는 게 아니라 is much more common and natural. Again, because this includes the 는 것 principle, this version of the form is used for verbs. Other versions of this form are A + 은/ㄴ 게 아니라 and N+ 이/가 아니라.

It’s not that I don’t like them, we just don’t get along well.

제가 그 사람을 싫어하는 게 아니라 우리는 그냥 잘 어울리지 못해요.

I’m not eating, I’m studying.

저는밥을먹는 아니라 공부하고 있어요.

The most delicious Korean food isn’t kimchi, it’s samgyeopsal.

가장 맛있는 한식은 김치가 아니라삼겹살이에요.

뭔

This particle is a shortened version of 무슨, meaning what / which one / what kind of. This is a contraction which sounds very informal, even when used with a formal sentence structure such as 습니다. It will sound rude if said to anyone older or anyone who you don’t know very well. Because of this, it’s fairly uncommon to hear this grammar being used unless you happen to be around a group of very close friends. Here are some examples of how it can be used:

What do you mean?

무슨말이야?

뭔말이야?

What jealousy?! / I’m not jealous!

무슨질투?!

뭔질투?!

뭔가

This grammar principle is actually a combination of 3 different forms: 무엇 (what / something), 이다 (it is / there is), and (으)ㄴ 가(요).

For a quick overview of (으)ㄴ 가(요), this is a sentence ending where the speaker is indirectly asking about something which they are curious about. It’s a softer, less direct way of asking a question and is best translated in English as ‘I wonder’. For example:

I wonder, how much is this?

이건얼마 인가요?

I wonder, will you come tomorrow?

내일도오실 건가요?

Combining these principles then, we have 무엇 + 이다(there is something or it is something), and then 무엇 인가(요) (I wonder if there is something, or I wonder if it is something). 무엇 인가(요) is almost always shortened to 뭔가(요).

I wonder…it’s something that you cant figure out, right?

뭔가모르겠지?

If it’s not that, I wonder what it is?

그게 아니라면 뭔가?

뭔가 Additional Meanings

Alongside the explanation above, there are two other ways in which 뭔가 can be used. Firstly, it can be used as a filler word when you are trying to pad out your speech or are struggling for your next word. Secondly, 뭐 and (으)ㄴ 가요 can sometimes simply mean ‘something’ without any nuance of indirect questioning, like in these examples:

I feel like something sweet.

뭔가 단 것이 땡긴다.

Yuseok, you have something on your face.

유석 씨의 얼굴에 뭔가묻었어요.

This second usage is what is being used in the example from the Game Administrator in this scene. He is saying that it seems (것 같다) that something (뭔가) has been misunderstood (오해가 있는것). Obviously then, the translation here is very accurate to what is actually being said.

거든(요) in a second clause

This grammar principle is placed at the end of a clause to indicate the reason for something or provide an explanation. Most of the time, you’ll see 거든(요) used at the end of a fragment or incomplete sentence as a tag on explanation to what has previously been said. Here are some examples of this:

These days, I go to bed too late. It’s because I have so much work.

저는 요즘에 너무 늦게 자요. 일이 많거든요.

Come to our house this Friday night. We moved house recently (so we’re having a party).

이번 주 금요일에 우리 집에 저녁 드시러오세요. 얼마 전에 새집으로 이사했거든요.

Will you come to our house for dinner tomorrow? It’s my birthday.

내일 저희 집에서 식사 함께 하실래요? 내일이 제 생일이거든요.

It is also possible to use 거든(요) in full sentences, like so:

It’s because if I get the chance, I’d like to try working at a Korean company in the future.

나중에 기회가 되면 한국 회사에서 일해 보고 싶거든요.

거든(요) in a first clause

거든(요) has a slightly different meaning when used in the first clause instead of the second clause of an explanation. If used at the end of the first clause, 거든(요) indicates that you are providing information which will help the listener to make sense of the next clause. Here are some examples of how this can be used:

I haven’t done the work yet, so I’ll probably have to go to the office to do it.

일을 아직 안 했거든요. 그래서 오늘 회사에 사거 해야 될 것 같아요.

I marked it in our calendar. Don’t forget, and make sure that you come on the day.

우리가 언제 달력에 표시했거든요. 깜빡하지 말고 그 날에 꼭 와야 돼요.

This is the way in which Han Mi-Nyeo uses 거든(요). She is telling the Game Administrator that she has a baby to allow her to then explain that she hasn’t named it yet so she couldn’t register the birth of her baby. This is one of the first scenes that hints towards Han Mi-Nyeo’s intelligence and manipulative abilities. She most likely doesn’t have a baby, but pleads desperately with the Game Administrator to let her go to be with her child. This is very smart, considering that Korea has a very low birth rate. The rarity of children has caused people to value them a lot, and you will often find people trying to interact with childrenandgiving them freebies like sweets or yakult drinks wherever they go. In normal circumstances, Mi-Nyeo would have been sent away immediately.

선생님

As beginners, Korean learners are told that 선생님 is a formal way to refer to a teacher. So why is Han Mi-Nyeo calling the Game Administrator 선생님 when obviously he isn’t a teacher?

선생님 actually has an additional meaning that is used quite frequently and is very important to understand. It can be used to address someone in a formal way, and is used often when you need the attention of a stranger, or someone whose name is unknown. Here are some examples of how it may be used:

Excuse me, you can’t be in here.

실례합니다,선생님 여기 계시면 안 됩니다만.

Excuse me, what’s happening?

실례합니다,선생님 무슨 일이야?

Excuse me, is there a problem?

선생님 무슨 문제 있어?

Here, Han Mi-Nyeo is calling the Game Administrator 선생님 because she doesn’t know his name, but also because she wants to put herself in a position far below him and show respect in the hope that she can appeal to him and be released from the game. This is also why she is kneeling down and clasping her hands together. Her body language and speech in this scene all highlight that she is trying to show to the Game Administrator that he is a highly respectable person, whilst lowering herself in an attempt to gain his pity. Here, the translation of ‘please, sir’ is actually fairly good. It expresses her desperation and desire to appeal to him by showing respect well.

아/어(서)

As you may have already learned, 아/어(서) is used to connect two clauses in order to indicate that one thing happened after another. When using 나/어(서) in this way, 서 is optional.

I’m going to sit down and relax.

나는 앉아서 쉴 거야.

I’m going to go to school and study.

저는 학교에 가서 공부할 거예요.

아/어서

Another usage of 아/어서 is to indicate how or by what means the second action happens. In this usage, 서 cannot be omitted.

I solved the problem using the new computer.

새로운 컴퓨터를 써서 문제를 풀었어요.

I explained it by using many types of examples.

몇 가지 예를 사용해서설명했어요.

They used the globe to draw a map.

지구본을 사용해서 지도를 그렸어요.

As you may already know, when 하다 and 어 are combined, they create 해. Therefore, 해서 is used when 아/어서 is added to a verb ending in 하다. As mentioned in the 아/어(서) section however, the 서 can be omitted sometimes, so you may simply see 해 as the connective. A variation of 해 is 하여, which is seen most commonly in written Korean. This is simply the original version of 해 without the two particles joining together.

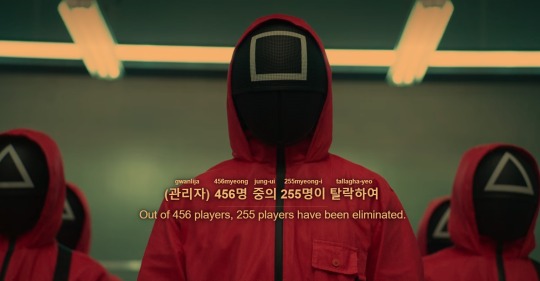

This is what we see in the above example. The full sentence said by the Front Man is ‘456명 중의 255명이 탈락하여, 첫 번째 게임을 끝마친 참가자는 201명입니다’. Here, the connector 아/어(서) is being used to indicate that out of 456 players, 255 players have passed, and the number of players who finished playing in the first game is 201. The 서 has simply been omitted and the variation 하여 has been utilised instead.

중의 and 중에

This grammar principle is used to indicate that a statement is being made about a group of people. The English equivalent would be ‘out of’ or ‘amongst’.She is the youngest amongst three girls.

그녀는 세 자매 중의막내이다.

Amongst our group, someone is left handed.

우리중의 어떤 사람은 왼손잡이다.

중에 can be used in exactly the same way. The two are interchangeable in this context.

There is no such person amongst us.

그런 사람은 우리 중에는 없다.

중에 Additional Meanings

Although 중에 can be used to mean amongst a group, it can also be used to show that something is taking place in the middle of another action. This usage is a very literal combination of 중 and the particle 에. If this principle feels difficult to learn, one way to practise could be creating sentences using the particle 에 for time, and changing the first part of the sentence into something which was happening whilst the action takes place and adding in 중.

I happened to meet my friend at 12 o’clock.

12시에 친구를 우연히 만났다.

Whilst I was going home, I happened to meet my friend.

집에 가는 중에 친구를 우연히 만났다.

My doorbell suddenly rang whilst I was in the middle of cooking.

요리 하는 중에 갑자기 누가 초인종을 눌렸어요.

는 중

If you’re unfamiliar with English grammar, the present progressive tense is used when you are in the middle of a certain action, or when that action is in progress. In English, these words usually end in the -ing suffix (eg. studying, writing, reading). When studying Korean as a beginner, one of the first grammar principles that you learned was probably 고 있다, which is the Korean equivalent of this form, however, you can also use 는 중 to show that something is in the present progressive tense. This grammar is used in exactly the same way as 고 있다, as you can just place it directly onto the end of the verb stem. This form is slightly less common than 고 있다, but is still used quite frequently and is good for adding variation to your speech or writing.

I’m studying.

나는 공부하는 중이다.

My brother is on a blind date.

오빠가 미팅을 하는 중이에요.

You may have noticed that all of the previous examples for 중에 also incorporated the 는 particle. This is because these sentences used both the 는 중 and 중에 grammar principles simultaneously to indicate that something was already taking place, and whilst that happened something else occurred. Using these two forms combined is a great way to easily impress native Koreans since it shows that not only do you know two intermediate forms, you also know how to combine them.

A 하고 B 중에(서)

This principle is used to indicate that there is a choice between 2 or more things. This principle is extremely useful if a choice needs to be made between several options, or something needs to be distinguished. Although 하고 is commonly used, you can also use 과/와 and this would still be grammatically correct. You may also use 중에(서) after a the name of a group or a collective noun, as ‘group’ indicates that there are several things involved to choose/make a distinction from.

Between Busan and Seoul, where do you want to go?

부산하고 서울 중에 어디 가고 싶어요?

Between design and practicality, which do you think is more important?

디자인하고 실용성 중에서 어느 게 더 중요해요?

Between all of my classes, geography is my favourite.

수업 주에 지리 수업을 제일 좋아해요.