#subcultures

In academic circles, we have a half-joking-but-not-really saying: “All Research Is Me-Search,” and Leigh Cowart’s new book has taken that dictum to titanic new heights and visceral, evocative depths.

Cowart is a former ballet dancer, a biologist who researched Pteronotus bats in the sweltering jungles of Costa Rica, and a self-described “high-sensation-seeking masochist.” They wrote this book to explore why they were like this, and whether their reasons matched up with those of so many other people who engage is painful activities of their own volition, whether for the pain itself, or the reward afterward. Full disclosure: Leigh is also my friend, but even if they weren’t, this book would have fascinated and engrossed me.

Hurts So Good is science journalism from a scientist-who-is-also-a-journalist, which means that the text is very careful in who and what it sources, citing its references, and indexing terms to be easily found and cross-referenced, while also bringing that data into clear, accessible focus. In that way, it has something for specialists and non-specialists, alike. But this book is also a memoir, and an interior exploration of one person’s relationship to pain, pleasure, and— not to sound too lofty about it— the whole human race.

The extraordinarily personal grounding of Hurts So Good is what allows this text to be more than merely exploitative voyeurism— though as the text describes, exploitative voyeurism might not necessarily be a deal-breaker for many of its subjects; just so long as they had control over when and how it proceeds and ends. And that is something Cowart makes sure to return to, again and again and again, turning it around to examine its nuances and infinitely fuzzy fractaled edges: The difference between pain that we instigate, pain that we can control, pain we know will end, pain that will have a reward, pain we can stop when and how we want… And pain that is enforced on us.

Read the rest of “Review: Hurts So Good: The Science and Culture of Pain on Purpose, by Leigh Cowart”atTechnoccult.net

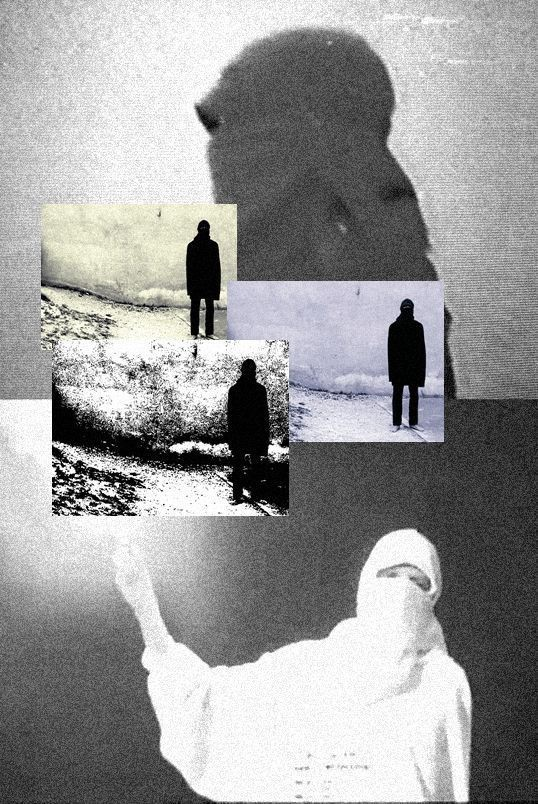

Raf Simons is known to many, but “half-understood” by the majority. Are we talking fashion, here? Not only, we are also taking into consideration the creative process behind a collection, its symbols (philosophically and sociologically speaking), aesthetics and style, feat. a in-depth study of the Zeitgeist, and its warriors — the members of subcultures.

‘Many of his early collections recontextualized pieces you would already know: the bomber jacket associated with skinheads; the balaclava with criminals; or the corporate uniform of white shirts and black suits. These he mashed up with remnants of his own life and obsessions.’ — Steff Yotka, Vogue

‘His idols are worn on sleeves, literally, and his personal passions bleed through in the music that plays at his shows, the books and art installations he organizes, and the films he directs. And yet, somehow, he is not nostalgic, pushing the limits of how we dress and what we could be.’ — Steff Yotka, Vogue

Talking about the music he plays at his shows, here is a comprehensive selection: Raf Simons — show soundtracks, feat. of course, New Order, among many others.

Read more on Raf’s art/fashion on Grailed: ‘The 10 Greatest Raf Simons Collections Ever’

‘There’s no argument that Raf Simons is lauded as one of the most important designers of all time. His influence on fashion stretches far and wide and there’s little within that realm that he has not conquered. From elevating his own eponymous label to a worldwide cult favorite to wildly successful creative direction stints at Jil Sander and Dior, Raf has found success at nearly every level of the industry.

His range as a designer is perhaps what makes him such an inspiring creative force. To date, his collections have done it all, from progressive men’s tailoring to subversive, graphic streetwear. Having just shown his first NYFW collection as chief creative officer of Calvin Klein, there’s no better time than now to reflect on some of his most iconic men’s collections to date.’

Watch these videos, too:

How Raf Simons Revolutionized the Fashion World / VFILES.DATA

Raf Simons the Fashion God | 3 Minute Minidoc / M2M

There is also a Tumblr blog dedicated to the genius of Raf: In The Name Of Raf

Last but not least, here is an interview about art, fashion, music, and much more: ‘RAF SIMONS IN CONVERSATION WITH HANS ULRICH OBRIST: PLOTTING AN ARTISTIC FUTURE’.

‘As Gilbert & George say, “To be with art is all we ask.” But then of course, after you invited artists to create a store, the next step of this integration was that you actually started to create a collection together with Sterling. How did that come about?

Maybe these are two weird words to place here, but the art that I look at and the art that I collect makes me very happy and calm. Whereas the fashion world can be extremely restless, stressed, and nervous. As a creative animal, it gives me an enormous satisfaction, curiosity, and happiness to enter the world of an artist that I’m interested in. It’s going into their brain and seeing how they think. What is an artwork about? How does it connect to the world? How does it connect to people?’

A little intro to subcultures.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines a subculture as ‘a cultural group within a larger culture, often having beliefs or interests at variance with those of the larger culture.’

David Riesman, circa 1950: “which passively accepted commercially provided styles and meanings, and a ‘subculture’ which actively sought a minority style … and interpreted it in accordance with subversive values”

Dick Hebdige, in his 1979 book Subculture: The Meaning of Style, that a subculture is a subversion to ‘the ‘straight’ world’. Subcultures bring together the neglected, the ones that can’t (or don’t want to) conform to the standards and rules of ‘normal society’, and give them a place and a sense of identity.

In 2007, Ken Gelder created a code that helps us distinguish subcultures from countercultures, based on the level of immersion in society. Gelder argues that members of subcultures are seen as ‘idle’ and ‘parasitic’ by society; they are not ‘class-conscious’ as they reject traditional class definitions; have a strong association with territory — e.g. the ‘street’, the ‘hood’ — rather than property; they embrace the group like it was a proper family, looking for belonging; like stylistic excess and exaggeration; refuse massification.

Documenting subcultures — photographers.

Here is a list of photographers that documented some subcultures throughout the years. Listed in no particular order (because f*ck the rules).

Derek Ridgers, 78–87 London Youth. You can follow Derek on Twitter, and see more of his skinheads shots on BuzzFeed.

Gavin Watson, Skins.

‘I had no professional photographic goals, I was more interested in being in a skinhead gang with a bit of photography on the side. I was a nervous photographer, and I still am. I’ve never gone up to a stranger and asked to take their photograph. I just couldn’t photograph other people, so it was all about my friends. My life was based around my friends, we all were all skinheads together, we all were teenagers together. If I hadn’t actually been a skinhead and set out to photograph them, the result would be very different. They’d all be V signing and shouting “fuck off, mate!”. It’s why I haven’t got the atypical pictures of what society think skinheads are, or even what skinheads think skinheads are.’ — Gavin Watson

Owen Harvey — Skinheads, Suedes, Mods, Lowriders, and other subcultures

Janette Beckman — various musical subcultures

“You could be chubby, a few teeth missing, a funny haircut — it didn’t matter. The best thing about punk? It was inclusive. You just had to have character and attitude. That made those pictures.” (via The Guardian)

Dennis Duijnhouwer, Gabbers

Exactitudes — a bit of everything

‘Photographer Ari Versluis and stylist Ellie Uyttenbroek have long started Exactitudes, a project that, put it simply, is a striking visual record of more than three thousand neatly differentiated social types the artists have documented over the last twenty years. Started in 1994 in the streets of Rotterdam, this overarching and on-going project portrays individuals that share a set of defining visual characteristics that identifies them with specific social types. Be it Gabbers, Glamboths, Mohawks, Rockers or The Girls from Ipanema, Versluis and Uyttenbroek’s extremely acute eye allows them to discern specific dress codes, behaviours or attitudes that belong and characterise particular urban tribes or sub-cultures. Once they recognise an individual that fits the characteristics of a given group, they invite such person to be photographed at the studio with the only requirement of wearing the very exact same clothes s/he was wearing at the time they first encountered.’

Mark Oblow, skateboarding

‘I picked up a camera because I was skating with all my heroes! Hosoi, Natas, Gonz, Cab, Tony Hawk, Lance Mountain, Tommy Guerrero, Gator, Jason Lee, etc. This list could keep going for days. It was hard because I wanted to skate too, but I learned to split it up with taking photos. I met Kevin Thatcher and he was a big influence on me along with Bryce Kanights — pro skater/pro photographer. He was the shit!’ (via Lodown Magazine)

James Mollison, music fans.

From Mollison’s website: ‘His third book, The Disciples was published in 2008 — panoramic format portraits of music fans photographed before and after concerts.’

Oasis — Manchester Stadium, Manchester, UK, 3rd July 2005

Documenting subcultures — other links and sources.

Reddit, Twitter, Tumblr, Instagram and Pinterest is where subculture still live. A couple of interesting/relevant ones

Football casuals

From Vice: ‘Why Is Casual Culture Still Relevant In Football and Fashion?’

@thecasualultra on Twitter

@CasualMind_ on Twitter

Techwear

@techwearfits on Instagram

r/TechWear on Reddit

Great blog post on Aphrodite’s website, analysing the success of Clarks among many subcultural groups: ‘From Jamaica to Japan: Clarks’ Subcultural History‘

‘The Jamaican rude boy took pride in their appearance with Clarks Desert Boots establishing the brand’s flagship silhouette as a staple item. Being expensive, stylish and made in England gave the shoe a sign of affluence, as well as a counterculture strike to the colonisation of the Caribbean country. Practically, the boot was versatile, strong and could withstand lots of wear; its crepe sole made barely a sound affording the wearer with an element of surprise that quickly earned Clarks an unsavoury reputation with Jamaican law enforcement.’

Another article on the subject: ‘Vybz Kartel puts Clarks footprint on Jamaica’ (source: The Guardian)

‘"Clarks is as much a part of the Jamaican culture as ackee and saltfish and roast breadfruit, I swear to you,“ says Kartel, whose real name is Adijah Palmer. "Policemen wear it, gangsters wear it. Big men wear it to their work. Schoolchildren wear it to school.”

If Clarks have long been in Britain the shoes of schoolchildren and pensioners, in Jamaica they are a long-standing symbol of upward social mobility, valued for their versatility and – important in a tropical climate – their breathability.

“The generation who had immigrated to England to work in that period after the second world war would return to Jamaica wearing these Clarks, and people developed a fascination,” Ranx says. “You go back to Jamaica on holiday, the first thing they ask you for is: ‘Bring back a traditional Marks & Spencer string vest, or a pair of Clarks.’”

By the time reggae exploded internationally in the 1970s, Clarks were the preferred footwear for Rastafarians and “baldheads” alike. Rummage through LPs from reggae’s golden era, and you’re likely to turn up at least a few photos of rude boys with their trouser legs rolled up to reveal ankle-length desert boots. But it was in the 1980s, as the social consciousness of the Bob Marley era gave way to dancehall’s rampant materialism, that the shoes gained iconic status. “The 80s was a hyper-materialistic time in Jamaica and Jamaican music,” says Jason Panton, owner of the Kingston fashion boutique Base Kingston, and I&I Clothing, a Jamaican streetwear brand. “After the whole scare over Jamaica going socialist, a lot of importance was placed on brand names. People wanted other people to know him stepped up him life. Part of the way you show that is you have a Clarks, you have a gold chain around your neck, and you ain’t afraid to wear it on road.” The teenage toaster Little John (not to be confused with rapper/producer Lil’ Jon) even scored a 1985 hit with Clarks Booty. “Hol’ up yuh foot and show your Clarks Booty,” went the song’s chorus, a riff on Yellowman’s Zungguzungguguzungguzeng, “Fling out your foot because your shoe’s brand new."’

From the inspiring subculture-dedicated section of Fred Perry’s website: ‘Casely-Hayford’

‘Q - The idea of passing garments down through the generations feels very appropriate for now, as consumers are becoming increasingly focused on a slower, more ethical approach to fashion…

A - I really wanted to hit home that message, of the foundation of the collaboration. I hope it adds value to the garments, so maybe people will look after them longer and cherish them.’

‘Hardc*re music stands for purpose, community, expression. And playing every single second like it’s your last. The aggressive spawn of late-70’s punk rock, hardc*re has evolved and mutated through the decades, spitting out countless subgenres and identities.

But what has always remained true, is hardc*re’s sense of confidence. Confidence to speak your mind, confidence to Do It Yourself, confidence to be who you are.

And with that confidence comes styles to match. Styles that, like the music, have something to prove, a statement to make.‘

Sweet post (as usual) on Oi Polloi’s blog: ’A BRIEF HISTORY OF NIKE ACG’. ‘In the early 70s a new breed of long-haired rock scramblers known as the Stonemasters had gathered around the cliffs of Yosemite, taking the laid-back surf-style they’d seen on the beaches of California out into the country. (…) There’s an old interview somewhere out there where one of the original Stonemasters talks about how they’d purposely go out in white painter pants and bright shirts just to wind up the more traditionally-minded climbers. Footwear followed suit, as clunky leather clodhoppers were thrown out in favour of lightweight approach shoes and nimble running trainers.’

From Eric Brightwell’s website: ‘Whereas middle-class subcultures like beatniks and trads often seemed to dress down, working-class subcultures have historically favored dressing up. The smart Fred Perry shirt was thus favored by working-class subcultures like skinheads (and suedeheads) in the 1960s; (northern) soul boys, punks and rude boys in the 1970s; casuals in the 1980s; Britpoppersin the 1990s; and chavs in the 2000s. The brand’s importance to various British youth subcultures was highlighted in filmmaker Don Letts’s documentary series, Subculture (2012).

PERRY BOYS

As written earlier, there was also the Perry Boy subculture. With roots in the Soul Boy subculture, Perry Boys emerged as something distinct around 1977 and ’78. This is probably sacrilegious to say for some Mancunians but Perry Boys were seemingly almost certainly influenced by their peers and rival subculture — the Scallies of Liverpool. For most of the 1970s, Liverpool FC placed at or near the top of the First Division. Scallies followed their team to the continent and would graft and shoplift so that they could wear expensive and exclusive labels. Meanwhile, back in the North, Manchester United, spent most of the decade trying not to get relegated. Though Perry Boys came to be primarily associated with football hooliganism, when they first appeared it was naturally away from the terrace in nightclubs such as Manchester’s legendary Pips.

As with all the best youth subcultures, music played a central role for Perries. The Perry soundtrack included Disco,Soul,Roxy Music,David Bowie, and neo-psychedelic post-punk bands. Favored American neo-psychedelic bands included Athens‘sR.E.M., Milwaukee‘s Plasticland, Rhode Island‘s Plan 9, St. Paul‘s Hüsker DüandLos Angeles‘s Paisley Underground (The Dream Syndicate,Green on Red,Rain Parade, and The Three O’Clock) as well as Liverpool’s Echo & the BunnymenandTeardrop Explodes. Local post-punk bands with Perry Boy elements in their audience included Joy Division,The Chameleons,Crispy Ambulance,Magazine, and Vibrant Thigh. And they liked The Cramps. Tellingly, few if any bands from London made the grade.’

From Dangerous Minds: ‘Ian Hough’s amazing books, Perry Boys: The Casual Gangs of Manchester and Salford and Perry Boys Abroad: The Ones That Got Away, are part-memoir and part cultural history but both are low on photos. Perry Boys, despite having roots in the Northern Soul subculture, were not associated with only one specific musical genre, like the slightly later New Romantics. As a result they were not as carefully documented visually as other subcultures, which is a real shame.Hough describes the Perry Boy look: ‘Bowie and Bryan Ferry were the dual lighthouses that served to guide kids’ blinkered coolness into a new harbour. Then, they slowly emerged, from Northern Soul and football roots, to coalesce in a new look that seemed so right; Clarke’s Polyveldt, Hush Puppies and Adidas Kick were the featureless tadpoles from which numerous forms sprang. Peter Werth polos, burgundy chunky sweaters and Fred Perries were the shirts. Levis and Lois were the jean. The hairstyle was the wedge.’

Amoeba blogger Eric Brightwell included a few more iconic clothing brands in his description: ‘In addition to Fred Perry, the Town Boys (as they were also sometimes known) also favored (preferably burgundy-colored) Peter Werth shirts, Fila Borgs, raglan sleeve shirts, Harrington jackets, Sergio Tacchini and later replica football kits. Preferred trousers included Levi’s 501s or Sta-Prest, Lee corduroys, and Lois jeans. Popular shoes included Adidas Stan Smith, docksiders, Kios, and Kickers. Other approved labels included Aitch,French Connection, FU, and Second Image.’

Fred Perry traditional pique tennis shirts were as sought after as Izod Lacoste polo shirts among the upper middle class in the U.S. The mods in London had been wearing them since the early ‘60s, as had skinheads, suedeheads, rude boys and punks in Manchester and Salford, who had worn the black-champagne-champagne version. But the shirt acquired a legion of unlikely poster boys in the late ‘70s.

Perry Boys were notorious for attending Manchester United matches abroad and shoplifting luxury brand clothing and jewelry from upscale boutiques. They were also willing to get blood on those expensive shirts. Hough describes the Perry Boys’ reputation for violence, which was immortalized in The Fall’s Mark E. Smith’s song “City Hobgoblins”: ‘People feared Perries, but they were a rare sight in the mid-70s, favouring night-life over day, Soul over Glam-Rock and music over football. Despite the obscurity, they were feared as nasty lads, very insular and ready to strike at anyone who looked at them, full stop.’

In academic circles, we have a half-joking-but-not-really saying: “All Research Is Me-Search,” and Leigh Cowart’s new book has taken that dictum to titanic new heights and visceral, evocative depths.

Cowart is a former ballet dancer, a biologist who researched Pteronotus bats in the sweltering jungles of Costa Rica, and a self-described “high-sensation-seeking masochist.” They wrote this book to explore why they were like this, and whether their reasons matched up with those of so many other people who engage is painful activities of their own volition, whether for the pain itself, or the reward afterward. Full disclosure: Leigh is also my friend, but even if they weren’t, this book would have fascinated and engrossed me.

Hurts So Good is science journalism from a scientist-who-is-also-a-journalist, which means that the text is very careful in who and what it sources, citing its references, and indexing terms to be easily found and cross-referenced, while also bringing that data into clear, accessible focus. In that way, it has something for specialists and non-specialists, alike. But this book is also a memoir, and an interior exploration of one person’s relationship to pain, pleasure, and— not to sound too lofty about it— the whole human race.

The extraordinarily personal grounding of Hurts So Good is what allows this text to be more than merely exploitative voyeurism— though as the text describes, exploitative voyeurism might not necessarily be a deal-breaker for many of its subjects; just so long as they had control over when and how it proceeds and ends. And that is something Cowart makes sure to return to, again and again and again, turning it around to examine its nuances and infinitely fuzzy fractaled edges: The difference between pain that we instigate, pain that we can control, pain we know will end, pain that will have a reward, pain we can stop when and how we want… And pain that is enforced on us.

Read the rest of “Review: Hurts So Good: The Science and Culture of Pain on Purpose, by Leigh Cowart”atTechnoccult.net