#syntax

An interesting question found its way into our inbox recently, asking about relative clauses in Swedish, and wondering whether their unique characteristics might pose a problem for some of the linguistic theories we’ve talked about on our channel. So if you want a discussion of syntax, Swedish, and subjacency (with some eye-tracking thrown in), this is for you!

So yes, there is a hypothesis that Swedish relative clauses break one of the basic principles by which language is thought to work. In particular, it’s been claimed that one of the governing principles of language isSubjacency, which basically says that when words move around in a sentence, like when a statement gets turned into a question, those words can’t move around without limit. Instead, they have to hop around in small skips and jumps to get to their destination. To make this more concrete, consider the sentence in (1).

(1) Where did Nick think Carol was from?

The idea goes that a sentence like this isn’t formed by moving the word “where” directly from the end to the beginning, as in (2). Instead, we suppose that it happens in steps, by moving it to the beginning of the embedded clause first, and then moving it all the way to the front of the sentence as a whole, shown in (3).

(2a) Did Nick think Carol was from where?

(2b) Where did Nick think Carol was from _?

(3a) Did Nick think Carol was from where?

(3b) Did Nick think where Carol was from _?

(3c) Where did Nick think _ Carol was from _?

One of the advantages of supposing that this is how questions are formed is that it’s easy to explain why some questions just don’t work. The question in (4) sounds pretty weird — so weird that it’s hard to know what it’s even supposed to mean. (The asterisk marks it as unacceptable.)

(4) *Where did Nick ask who was from _?

Theexplanation behind this is that the intermediate step that “where” normally would have made on its way to the front is rendered impossible because the “who” in the middle gets in its way. It’s sitting in exactly the spot inside the structure of the sentence that “where” would have used to make its pit stop.

More generally, Subjacency is used as an explanation for ‘islands,’ which are the parts of sentences where words like “where” and “when” often seem to get stranded. And one of the most robust kinds of island found across the world’s languages is the relative clause, which is why we can’t ever turn (5) into (6).

(5) Nick is friends with a hero who lives on another planet

(6) *Where is Nick friends with a hero who lives _?

Surprisingly, Swedish — alongside other mainland Scandinavian languages like Norwegian — seems to break this rule into pieces. The sentence in (7) doesn’t have a direct translation into English that sounds very natural.

(7a) Såna blommor såg jag en man som sålde på torget

(7b) Those kinds of flowers saw I a man that sold in square-the (gloss)

(7c) *Those kinds of flowers, I saw a man that sold in the square

So does that mean we have to toss all our progress out the window, and start from scratch? Well, let’s not be too hasty. For one, it’s worth noting that even the English version of the sentence can be ‘rescued’ using what’s called a resumptive pronoun, filling the gap left behind by the fronted noun phrase “those kinds of flowers.”

(8) Those kinds of flowers, I saw a man that sold them in the square

For many speakers, the sentence in (8) actually sounds pretty good, as long as the pronoun “them” is available to plug the leak, so to speak. At the very least, these kinds of sentences do find their way into conversational speech a whole lot. So, whether a supposedly inviolable rule gets broken or not isn’t as black-and-white as it might appear. What’s maybe a more compelling line of thinking is that what look like violations of these rules on the surface can turn out not to be, once we dig a little deeper. For instance, the sentence in (9), found in Quebec French, might seem surprising. It looks like there’s a missing piece after “exploser” (“blow up”), inside of a relative clause, that corresponds directly to “l'édifice” (“the building”) — so, right where a gap shouldn’t be possible.

(9a) V'là l'édifice qu'y a un gars qui a fait exploser _

(9b) *This is the building that there is a man who blew up

But that embedded clause has some very strange properties that have given linguists reasons to think it’s something more exotic. For one, the sentence in (9) above only functions with what’s known as a stage-level predicate — so, a verb that describes an action that takes place over a relatively short period of time, like an explosion. This is in contrast to an individual-level predicate, which can apply over someone’s whole lifetime. When we replace one kind of predicate with another, what comes out as garbage in English now sounds equally terrible in French.

(10a) *V’là l'édifice qu'y a un employé qui connaît _

(10b) *This is the building that there is an employee who knows

Interestingly, stage-level predicates seem to fundamentally change the underlying structures of these sentences, so that other apparently inviolable rules completely break down. For instance, with a stage-level predicate, we can now fit a proper name in there, which is something that English (and many other languages) simply forbid.

(11a) Y a Jean qui est venu

(11b) *There is John who came (cannot say out-of-the-blue to mean “John came”)

For this reason, along with some other unusual syntactic properties that come hand-in-hand, it’s supposed that these aren’t really relative clauses at all. And not being relative clauses, the “who” in (9) isn’t actually occupying a spot that any other words have to pass through on their way up the tree. That is, movement isn’t blocked like how it normally would be in a genuine relative clause.

Still, Swedish has famously resisted any good analysis. Some researchers have tried to explain the problem away by claiming that what look like relative clauses are actually small clauses — the “Carol a friend” part of the sentence below — since small clauses are happy to have words move out of them.

(12a) Nick considers Carol a friend

(12b) Who does Nick consider _ a friend?

But the structures that words can move out of in Swedish clearly have more in common with noun phrases containing relative clauses, than clauses in and of themselves. In (13), it just doesn’t make sense to think of the verb “träffat” (“meet”) as being followed by a clause, in the same way it did for “consider.”

(13a) Det har jag inte träffat någon som gjort

(13b) that have I not met someone that done

(13c) *That, I haven’t met anyone who has done

So what’s next? Here, it’s important not to miss the forest for the trees. Languages show amazing variation, but given all the ways it could have been, language as a whole also shows incredible uniformity. It’s truly remarkable that almost all the languages we’ve studied carefully so far, regardless of how distant they are from each other in time and space, show similar island effects. Even if Swedish turns out to be a true exception after all is said and done, there’s such an overwhelming tendency in the opposite direction, it begs for some kind of explanation. If our theory is wrong, it means we need to build an even better one, not that we need no theory at all.

And yet the situation isn’t so dire. A recent eye tracking study — the first of its kind to address this specific question — suggests a more nuanced set of facts. Generally, when experimental subjects read through sentences, looking for open spots where a dislocated word might have come from as they process what they’re seeing, they spend relatively less time fixated on the parts of sentences that are syntactic islands, vs. those that aren’t. In other words, by default, readers in these experiments tend to ignore the possibility of finding gaps inside syntactic islands, since our linguistic knowledge rules that out. And in this study, it was found that sentences like the ones in (7) and (13), which seem to show that Swedish can move words out from inside a relative clause, tend to fall somewhere between full-on syntactic islands and structures that typically allow for movement, in terms of where readers look, and for how long. This suggests that Swedish relative clauses are what you might call ‘weak islands,’ letting you move words out of them in some circumstances, but not in others. And this is in line with the fact that not all kinds of constituents (in this case, “why”) can be moved out of these relative clauses, as the unacceptability of the sentence in (14) shows. (In English, the sentence cannot be used to ask why people were late.)

(14a) *Varföri känner du många som blev sena till festeni?

(14b) Why know you many who were late to party-the

(14c) *Why do you know many people who were late to the party?

For reasons we don’t yet fully understand, relative clauses in Swedish don’t obviously pattern with relative clauses in English. At the same time, the variation between them isn’t so deep that we’re forced to throw out everything we know about how language works. The search for understanding is an ongoing process, and sometimes the challenges can seem impossible, but sooner or later we usually find a way to puzzle out the problem. And that can only ever serve to shed more light on what we already know!

What can silence tell us about the syntax of a sentence? How do we know what meaning to fill in when words are missing? In this week’s episode, we talk about ellipsis: what rules are at work to tell us how to use it, how sentence structure plays into what words we can leave out, and whether words are even missing at all, or just hiding.

We’re really glad to be back and sharing stuff with you all again! Looking forward to hearing what you have to say.

Inour recent video about pronouns, we discussed how we figure out just what they mean, since on its own, “he” or “himself” doesn’t seem to mean anything. At first glance, it looks as if reflexive pronouns like “himself” always have to refer back to some other nearby noun phrase — their antecedent. More precisely, reflexive pronouns and their antecedents co-refer, which means they both pick out the same thing in the world.

(1) Mark believes in himself.

But as we pointed out in this episode, that idea doesn’t really hold up when it comes to quantifying phrases, like “everybody” or “no soldier.” In the sentence below, the subject doesn’t really point to anything, but the pronoun still meaningfully connects up to it.

(2) None of Mark’s brothersunderstandthemselves as well as he does.

A more complete picture of reflexives, then, is one where they’re always bound to some nearby noun phrase, whether it’s a name, a quantifying expression, or even another pronoun. They don’t necessarily have to refer to anything, but that connection always has to be there. In other words, they have to be co-indexed with their antecedent, even if they don’t have that reference link.

In contrast to reflexives, regular pronouns like “her” and “he” don’t always need to be bound to something nearby, or even something far away. They can either skip over intervening noun phrases to connect up to a distant subject, as in (3), or else refer to that same person by way of the speaker physically pointing them out, like in (4).

(3) Delphine is worried about whether or not Cosima will forgive her.

(4) She’s worried about Cosima.

Of course, interpreting some sentences requires that ordinary pronouns act a lot like reflexives; assuming “they” in the sentence below is understood to be picking out a portion of Sarah’s sisters, we’re forced to suppose that it’s co-indexed with — and so bound to — the quantified phrase “most of Sarah’s sisters.”

(5) Most of Sarah’s sisters don’t even know they’re related.

The point is just that non-reflexive pronouns have a degree of freedom that reflexive pronouns don’t, and can maneuver in ways reflexives can’t. But this ends up raising an interesting question about certain kinds of sentences, like the one found in (6).

(6) Alisonknewshe was in trouble.

In principle, the sentence above has two separate paths to arrive at the interpretation where “she” refers to Alison: either “she” is co-indexed with the noun phrase “Alison,” or else “she” is open to picking out whoever is poking out the most in the conversation at that point in time, which by coincidence happens to be Alison. That is, “she” is either bound to the subject, and so indirectly referencing Alison, or else freely referring to the person named Alison directly, by way of the surrounding context.

That might seem like a distinction without a difference, and in this case it very nearly is, since there’s no detectable change in meaning (i.e., in either case, “she” winds up referring to Alison). We might even wonder whether it’s necessary to eversuppose that regular pronouns are bound, save when following quantifying words. Maybe, in all other cases, non-reflexive pronouns are simply free, choosing sometimes to co-refer with some other part of the sentence, and sometimes not to. After all, it seems a bit redundant to have two equally valid ways of arriving at the exact same result.

But as it turns out, there’s actually something we can do to tease these subtly separate meanings apart from each other, despite how closely tied together they might appear. To see how, consider the sentence in (7).

(7) Rachel went into hiding, because she had to.

Notice that the second clause is fairly easily understood to mean “because she had to go into hiding,” even though the verb phrase is nowhere to be seen. That’s because this represents an instance of ellipsis— the omission of part of a sentence when it’s clear what’s being cut out. In particular, when we encounter ellipsis, we always understand the missing material to be identicalto some nearby, suitably related string of words. After all, the second half of (7) can’t mean “because she had to stay safe,” as much as that might make sense. This identity condition on ellipsis helps us to quickly recover what’s left unsaid.

And though it might at first come across as counterintuitive, ellipsis is a surprisingly powerful way to get at a better understanding of the behaviour of pronouns. In fact, by making them disappear, we can actually end up clarifying how they work! Take a close look at this next sentence.

(8) Dr. Leekie went to his office, and Dr. Nealon did too.

Beginning with the assumption that “his” refers to Dr. Leekie, and not some third party that hasn’t been mentioned, the first half of the sentence is understood to mean “Dr. Leekie went to Dr. Leekie’s office.” Now, if we had arrived at this meaning by having the possessive pronoun “his” freely pick out Dr. Leekie, simply because it was convenient, we’d expect the missing part of second half of the sentence to match this choice word-for-word. That is, we’d expect the whole sentence to mean “Dr. Leekie went to Dr. Leekie’s office, and Dr. Nealon went to Dr. Leekie’s office.”

But that isn’t the only meaning we get. The sentence can also mean “Dr. Leekie went to Dr. Leekie’s office, and Dr. Nealon went to Dr. Nealon’s office.” The whole thing is ambiguous, because the missing material can be interpreted in two different ways. And if we assume that the absent verb phrase must be identical with the one in the first half of the sentence, as we did in (7), that initial VP must be capable of carrying two slightly different interpretations: one where “x went to Dr. Leekie’s office,” and one where “x went to x’s own office.” So, the pronoun “his” can either act like a ‘true’ non-reflexive pronoun, and directly pick out Dr. Leekie, or it can act more like a reflexive pronoun, binding it to the nearest available subject.

The fact that the second clause (and so the sentence as a whole) has two detectable meanings lets us peer into the inner workings of that first clause. It tells us that the first half of the sentence has two subtly distinct interpretations, and that two unique mechanisms are at play, all because pronouns have the option of being either bound or free.

So a completely natural phenomenon like ellipsis can be co-opted and used as a tool, to help shed light onto the otherwise sticky semantics of pronouns, and provide us with even more evidence that reflexives and non-reflexives both fit into the same basic category — with a few differences, for sure, but also more in common than you might have thought.

The comparative sentences that we talked about in our episode on grammatical illusions, like in (1) below, are surprising because of how far away people’s first impressions tend to sit from reality.

(1) More people have been to Montreal than you have.

When you give it a moment’s thought, it becomes clear there’s a sizeable gap between how sensible it seems at first glance, and how little information it actually communicates.

Even the illusory sentence in (2a) below, which was rated in experiments as being nearly as acceptable as the perfectly ordinary sentence in (2b), still falls apart when you try to put its pieces together. Spelled out, its meaning ends up as something like “how many girls ate pizza is greater than how many we ate pizza,” which doesn’t quite work; pronouns, even plural ones like “we,” can’t easily be combined with counting expressions like “how many.”

(2a) More girls ate pizza than we did

(2b) More girls ate pizza than boys did

But we still manage to interpret these sentences, in a way that fits the machinery made available by our mental grammar. As we discussed in the episode, the fact that we’re also able to count how many times something happened, in addition to how many there are of something, gives us a kind of half-working backdoor into understanding them. But, there’s another kind of illusion that’s even more striking, where there really isn’t any way at all to make sense of it. Try reading the following sentence aloud.

(3) The patient the nurse the clinic had hired met Jack

It seems pretty run-of-the-mill, pretty boring … except when you try to work out who’s doing what to who! It’s clear enough that the patient met Jack, and that the clinic’s doing some hiring, but what’s that nurse doing in the sentence? What’s his or her relationship with the patient? Or Jack? The nurse is just kind of … floating there, not really doing anything at all!

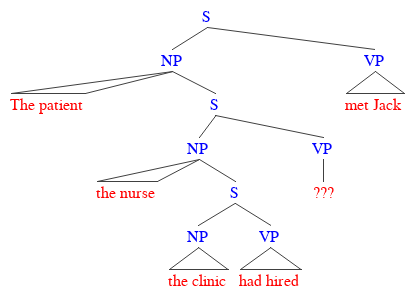

To make what’s going wrong more obvious, have a look at the simplified structure below. Each clause, whether it’s the overall sentence or an embedded one, has to have one subject noun phrase and one predicate verb phrase. Three clauses means three of each, but plainly, one of the verbs is simply missing in action!

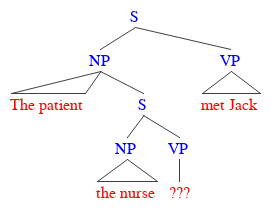

This problem becomes unavoidable when we trim our tree and take out that lowest clause, giving us “The patient the nurse met Jack,” which really can’t mean much of anything. In fact, it’s a violation of a basic condition on the shape that sentences can take, known as the Theta Criterion, which essentially demands that verbs and their subjects have to match up one-to-one.

Sentences like the one in (3), then, end up forming a class of grammatical illusions that result from the so-called missing-VP effect. And as remarkable as they might seem already, things get even stranger when we consider their supposedly grammatical counterparts. Take the modified version below, with the missing VP put back in its place.

(6) The patient the nurse the clinic had hired admitted met Jack

While everything’s where it should be, the sentence has now become just about impossible to follow — or, at least, a lot harder to understand on a first pass than the simplified version in (7), where the lowest clause has once again been pruned from the tree.

(7) The patient the nurse admitted met Jack

This difficulty with understanding an otherwise perfectly grammatical sentence — at least, according to the rules we know about — is thanks to a phenomenon that’s been pondered over since at least the 1960s: centre embedding. While placing one clause right in the middle of another works fine once, as in (7), applying the same rule a second time over produces an incomprehensible mess, like in (6) above or (8) below.

(8) The dog that the cat that the man bought scratched ran away

Even though we can diagram these sentences out and force ourselves to follow the plot from one branch to the next with a whole lot of effort, they don’t really sit well when we hear them out loud. And this seems to suggest an upper limit on how many times our rules can apply. Except, we can find cases where this upper limit goes right out the window, like this 3-clause deep sentence!

(9) The reporter who everyone (that) I met trusts said the president won’t resign yet

With a quantifying expression and a pronoun in place of two more definite noun phrases, everything seems to be back in working order. And even more complex sentences than this can be found in writing, though they’re fairly rare.

So, what’s going on here? And how can we account for all this seemingly contradictory data? To start, it’s worth considering one of the most cited papers in all of psychology, The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two by George A. Miller. This work became famous not for putting an upper limit on how many times some rule or other could apply, but on how much information we’re able to hold in working memory. Like the title says, there seems to be a fairly low ceiling on how many ‘bits’ or ‘chunks’ we can actively hold in our heads at any given time. And this applies to processing language as much as anything else.

In fact, in a pair of papers co-written with linguist Noam Chomsky the following decade, Miller hypothesized that our trouble with centre embedding has more to do with limitations on our memory than on our grammar — which could account for why fiddling with the details (e.g. swapping certain kinds of nouns for others) can sometimes get around the problem.

But then, what exactly is going wrong in the sentence in (6), and more importantly, why should something meaningless like (3) get a free pass? Well, research into how we handle these sentences is very much active, but at least one recent theory takes some steps towards shedding a little light on the contrast.

As we encounter each new noun phrase in a sentence like (3), an expectation is set up that we’ll reach the end of that clause; in other words, we anticipate that we’ll encounter a matching verb phrase for each one. But something starts going wrong when we get to the lowest, most deeply embedded part of the sentence (i.e., “the clinic”).

When we hear that first verb phrase “had hired,” it slots into the lowest open position pretty easily, because that lowest and most recently encountered clause is the current focus of our attention. But when we encounter that second verb phrase, “met Jack,” we’re left at a disadvantage: we’ve got two more open positions to fill, but each one completes a clause that’s been interrupted by another one, having had the focus of attention wrenched away from it. What’s worse, all the clauses are syntactically identical, with nothing to differentiate between them. And, so, the little working memory we have is overloaded. We default to connecting that second verb phrase to the first, highest clause, and mistakenly assume we’ve finished building the sentence.

This Interference Account supposes that the two remaining incomplete clauses that were interrupted by an intervening relative clause compete and interfere with each other, overwhelming our limited memory and forcing us into making the wrong choice. It also explains why we have so much difficulty with centre embedding more generally: since we default to connecting that second verb phrase up to the highest clause, believing we’ve completed the sentence as a whole, encountering a third verb phrase in a sentence like (6) or (8) completely violates our expectations, and throws us for a loop.

So, the existence of acceptable nonsense like (3) and of well-formed but incomprehensible sentences like (6) doesn’t mean that our grammar is broken beyond repair; it just means that the rules that make up language are owned and operated by less-than-perfect users!

Also in poetic or lyrical Spanish you may also find that verbs go at the very end of sentences. Partially because it’s dramatic, partially for rhyming.

So like consider No se habla de Bruno:

Bruno con voz misteriosa habló = Bruno with a mysterious voice spoke

In your regular Spanish you’d say Bruno habló con voz misteriosa “Bruno spoke with a mysterious voice”

The example saying habló at the very end pulls focus to the very end of the sentence and it’s dramatic

Another example of some changeable syntax is Isabela’s line:

Él vio en mí un destino gentil - una vida de ensueños vendrá. Y que así el poder de mi don como uvas va a madurar

“He saw within me a pleasant fate - a life of my dreams will come. And as such the power of my gift like grapes will ripen”

You see basic syntax in vio en mí rather than en mí vio which is also possible

Then you see una vida vendrá while more basic would be vendrá una vida

And, then again el poder de mi don va a madurar which could be phrased as va a madurar el poder de mi don

So it’s really a matter of where you want your emphasis and how emphatic you’d like to be

I will say that Spanish does sometimes like phrase something as SOV [subject object verb] and leave the verb all the way at the very end for things like poetry… partially for emphasis on the verb, partially because it’s easier to rhyme verbs in Spanish

SOV (and OSV potentially) in Spanish is also a kind of… suspension effect. You say your whole line and finish with a verb, so you’re sort of waiting to see what will happen. Isabela’s second line reads very much like that. It has a theatrical quality designed to capture attention and sort of keep you waiting

These kinds of constructions make more sense in context and many times carry over the sentiment into other languages; they’re things people do naturally