#womens history

Our final post for Women’s History Month 2017 comes again from Lorna Peterson, Emerita Associate Professor, University at Buffalo. The photo above was provided by family and printed on memorial service program and online obituaries; see The Oberlin News Tribune from Feb. 23 to Feb. 24, 2017 (accessed March 16, 2017)

Betty Jo Lanier Jenkins

February 27, 1936 - November 11, 2016

Raised on Historically Black College and University campuses (HBCUs) as well as two years in Monrovia, Liberia by her professor and diplomat father and librarian mother, influenced by a Quaker education in Iowa, and educated at a Seven Sisters college and an Ivy League university both in New York City, Betty Jo Lanier Jenkins lived an outstanding librarian career that encompassed the transitions of the United States civil rights era.

With the enactment of civil rights legislation in the 1960s, the development of public policy to implement the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965 was challenged by competing philosophies of integration versus black separatism within the black community. One response to that challenge was the establishment of a consortium and research institute of social scientists called MARC, Metropolitan Applied Research Center. Founded by psychologist Dr. Kenneth B. Clark, an aim of the institute was to provide a non-partisan forum for discussion between black and white politicians at city, state, and federal levels regarding the issues, policies and programs most relevant to the officials’ constituents and communities. Central to the MARC institute and its work was the library, and the head of that library was Betty L. Jenkins. Building the collection and directing the library influenced Ms. Jenkins’s own research and publication output. Her contributions to understanding race relations in the United States, as well as in American librarianship, are unique and foundational.

Born February 27, 1936, in Harris County, Texas, to professor, college administrator, and diplomat Ralphael O’Hara Lanier and librarian Garriette Lucile Green(e) Lanier, Betty was raised on the campuses of Texas State University for Negroes (now Texas Southern University), Hampton Institute (currently Hampton University), and other HBCUs along with her younger sister, Patricia. The family lived in Monrovia Liberia from 1946-1948, where her father was U.S. Minister to Liberia.

Educated for high school at the Quaker Scattergood Friends School in West Branch, Iowa, she developed a lifelong respect for Quaker principles, although she did not become a member of the Religious Society of Friends. She began her first college year at Grinnell College in GrinnelI, Iowa, and then transferred to Barnard College in New York City, where she earned a BA degree in history. Following the baccalaureate degree, she entered and graduated from the MS program in Library Service at Columbia University and later earned a MA in American history from New York University.

As part of her duties at MARC and at the request of the Hastie Group, Betty Jenkins, along with Susan Phillis, compiled and published the annotated bibliography Black Separatism in 1976. The bibliography is organized by two parts. Part 1 concerns separatism vs. integration within a historical perspective, citing and annotating materials from 1760-1953 and then followed by the twenty years since BrownvBoard of Education. Part 2 lists citations concerning the institutional and psychological dimensions regarding identity, education, politics, economics, and worship within the context of segregation and desegregation. Works that concern redressing racial inequities are also documented in Part 2 of the bibliography.

Betty Jenkins was a bibliographer and scholar librarian who published, presented, and created exhibits that documented the black experience in America. Works by Betty Jenkins include but are not limited by the following:

• a bibliographical essay written with Donald Franklin Joyce, “Aiming to publish books within the purchasing power of a poor people”: Black-owned book publishing in the United States, 1817-1987,” Choice February 1989, vol. 26, pages 907-913;

• solo authored and groundbreaking critical race biography of Ernestine Rose: “A white librarian in black Harlem,” Library Quarterly; July 1990, Vol. 60, pages 216-231; and

•Kenneth B. Clark: A bibliography, MARC 1970, 69 pages.

With assistance from the City College of New York (CCNY) Libraries, these additional contributions by Betty Jenkins are identified:

• CCNY issue of The Campus February 19, 1991: “Leading City College Black Faculty Discuss their Progress and Achievements at CCNY,” which is based on an event partly organized by Betty Jenkins;

• Principal Investigator for a National Endowment for the Humanities grant to host a conference and create conference proceedings for “We Wish to Plead our Own Cause”: Black-Owned Book Publishing in the United States 1817-1987 held May 1988 at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of NYPL;

• One of the curators of the CCNY Libraries Cohen Library Atrium exhibit “Parallel Worlds: African Americans in Harlem and Paris in the 1920s” February-June 2001.

As well as working for various libraries in the CCNY system, Betty Jenkins also worked at Howard University. Through her careful scholarship of bibliography, mounting exhibits, and writing a librarian biography within a context of race conflict and cooperation, Betty L. Jenkins preserved and interpreted the history and lives of Americans, particularly black Americans.

References

Ancestry.com. Texas Birth Index, 1903-1997 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations Inc, 2005. Original data: Texas Birth Index, 1903-1997. Texas: Texas Department of State Health Services. Microfiche.

Obituary of Betty Jo Lanier Jenkins of Oberlin Ohio, Dicken Funeral Home

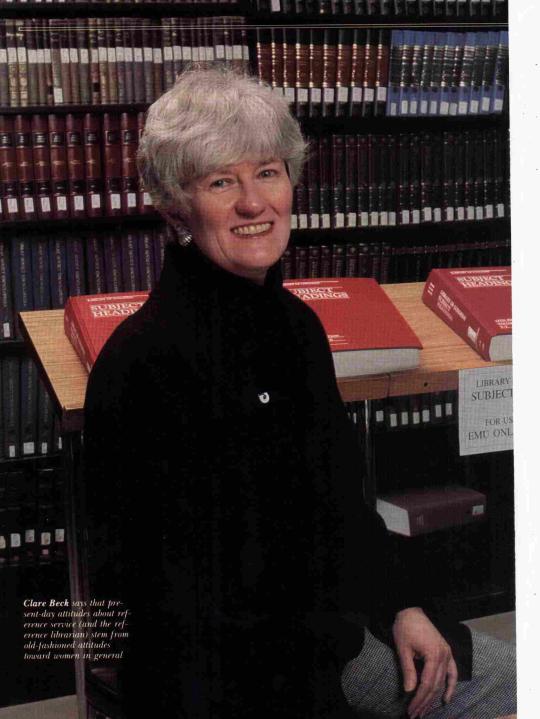

Photo from Library Journal, Volume 116 Issue 7, April 15, 1991, page 32; Eric Smith possible photographer. Caption reads “Clare Beck says that present-day attitudes about reference service (and the reference librarian) stem from old-fashioned attitudes toward women in general.”

Today’s post is from Lorna Peterson, PhD, Associate Professor (emerita), University at Buffalo. This is Lorna’s fourth (!) year writing for WoLH; she has previously submitted posts on Aurelia Whittington Franklin(2016),Leonead Pack Drain-Bailey (2015), and Clara Stanton Jones(2014).

Government documents librarian and feminist librarian historian Mary Clare Beck was born and raised in the American Midwest and is a graduate of the University of Chicago with an A.B. in history. She earned the Master of Library Science degree from the University of Denver, and a MA in interdisciplinary social studies from Eastern Michigan University. Her reading in sociology for the MA degree is where her interest to apply gender theory to the examination of the gendered dynamics of librarianship was generated. The result of this interest is a body of research that invigorates library and librarian history.

Beck’s career at Eastern Michigan University was one of achievement and honor when she retired at the rank of full professor from the University Library. Beck’s achievements include but are not limited to, being one of the founders of GODORT, the American Library Association’s Government Documents Round Table, giving invited lectures on library history, and championing librarianship by writing letters to library publications and educating the general public regarding library topics by publishing letters in national periodicals. Examples of such letters are “Defending the Depositories” published in Library Journal(February 15, 1988), a letter that appeared in the March 30, 2009 Wall Street Journal critiquing the press coverage of Laura Bush’s professional librarian role in contrast to the First Ladies who were lawyers, and comments on a proposed remodel of the NYPL research library which appeared January 10, 2012 in The Nation. As an alumna of the University of Chicago, Clare Beck has contributed to the alumni magazine regarding library matters with her “The importance of browsing,” which tempered for her fellow University of Chicago graduates the allure of automation with the appeal of serendipitous perusing of library stacks.

It is Clare Beck’s contribution to library science research, particularly historical research, where her greatest achievements are. Through enriching library science scholarship by examining the complexities of gender issues, Clare Beck advanced library science research beyond the studies of administrative positions and gender. With critical analysis through the lens of feminist theories and gender studies, Ms. Beck added significantly and uniquely to the library literature canon.

Her work, “Reference Service: A Handmaid’s Tale” (Library Journal, April 15, 1991, p. 32-37) examines library reference work and its 1980s self-identified crisis through the lens of gender. Citing sources outside of the discipline of library science, Beck’s article gives the profession a fresh way to frame the tradition as articulated by librarian Samuel Green, of having a helpful sympathetic friend at a desk to take random on demand requests. [ed. note: if you have access to Library Journal archives, you should look up and read this article. A representative quote: “Thus we have the concept of on-demand service provided by a woman at a public desk, always ready to lay aside other work to respond ‘incidentally’ to questions. The underlying image would seem to be that of Mother, always ready to interrupt her housework to attend of the problems of others.”]

Beck’s other works include “Genevieve Walton and library instruction at the Michigan State Normal College” College and Research Libraries (July 1989). Genevieve Walton has a profile in the Women of Library History blog. Archival research figures prominently in “A ‘Private’ Grievance against Dewey,” American Libraries (Jan 1996, Vol. 27 Issue 1, p62-64), a model work of library event history that goes beyond chronology and biography that is not hagiography. [ed. note: again, if you have archival access to American Libraries, give this one a read.]

“Fear of women in suits: dealing with gender roles in librarianship” was presented at the University of Toronto and then published in the highly regarded Canadian Journal of Information Science Vol. 17 no. 3, pp.29-39, 1992. Her biography of Adelaide Hasse, The New Woman as Librarian: The Career of Adelaide Hasse, Scarecrow Press, 2006, is rich with archival material and careful analysis .

Invited lectures such as “How Adelaide Hasse got fired: A feminist history of librarianship through the story of one difficult woman, 1889-1953,” as organized by Cass Hartnett of the University of Washington, “Fear of Women in Suits: Dealing with Gender Roles in Librarianship,“ and "Gender in Librarianship: Why the Silence?” (given at the Canadian Library Association conference) introduced professional librarians, library workers, and graduate library science students to a sociological feminist examination of the library and information science professions. In her career, invited talks and juried presentations were given at such organizations as the Michigan Academy of Science, Arts, and Letters (MASAL), Library and Information Science section, and ALA Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL).

Clare Beck’s contribution to library history advances our field with rigorous, iconoclastic research, enriching the understanding the practice of North American librarianship.

This post was submitted by Jason K. Alston on behalf of the Black Caucus of the American Library Association. Most of the information in the post comes from a BCALA Resolution of Respect for Rudd drafted by Dr. Sibyl Moses, with other information offered by Emily Guss, who personally knew and worked with Rudd. The image is courtesy of Chicago Public Library Archives, Special Collections.

Amanda Sullivan Rudd, the first female and first African-American commissioner of the Chicago Public Library, passed away on February 11, 2017 at the age of 93. Rudd served as the commissioner for CPL from 1982 until she retired in 1985. Prior to her appointment as CPL commissioner, Rudd served CPL as assistant chief librarian, community relations and special programs (1975), deputy commissioner (1975-1981), and acting commissioner (1981-1982). According to the Chicago Tribune, Rudd was a mentor to numerous younger colleagues at CPL, including eventual Librarian of Congress Dr. Carla Hayden. Hayden, in a letter to Rudd’s daughter, said, “Amanda was a trailblazer in the library field and I benefited greatly from her guidance during my time at the Chicago Public Library.”

A Greenville, South Carolina, native, Rudd told Ebony magazine in 1982 that she had a love for reading since the age of four, and that this love of reading led her to the doors of Greenville’s segregated public library at age 10. Rudd told Ebony that a white librarian barred her from entering; Rudd, therefore, satisfied her thirst for reading with books that her mother would buy her from a traveling salesman. Ebony stressed through their feature story on Rudd that she was a hallmark success story, going from a southern girl who was denied entry into her local library to heading what was then the nation’s largest metropolitan library system.

Rudd received her bachelor’s degree from Florida A&M University and held a master’s degree in library science from Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. Rudd served as a second grade teacher and an assistant director of school libraries in Cleveland during the 1960s. She was also an educational consultant with World Book Encyclopedia in Chicago during the 1970s. After her retirement from CPL, Rudd worked for distributor Baker & Taylor, and constructed annotated bibliographies of children’s books by, for, and about African-Americans.

Rudd is survived by one brother, two children, six grandchildren, and eight great grandchildren. She was preceded in death by her parents, seven siblings, and one granddaughter. Rudd’s daughter is Loretta Parham, an OCLC trustee and the CEO and Director of the Atlanta University Center Woodruff Library, an independent academic library for the shared benefit of four HBCUs (historically black colleges and universities)–Morehouse College, Spelman College, the Interdenominational Theological Center, and Clark Atlanta University.

Today’s post comes from Angie Neely-Sardon, who is the Reference Librarian/Instructor for the Mueller Campus of Indian River State College and former Computer Services Librarian for Bruton Memorial Library in Plant City, FL.

Above: Quintilla Geer Bruton (L) holds the State Library Award for 1963. Image used with permission from Plant City Photo Archives.

Quintilla Geer Bruton was born in 1907 in Walton, Kentucky. She moved to Plant City, FL, with her parents and sister on Thanksgiving Day, 1923. She was the valedictorian at Plant City High School for the Class of 1926. She attended Tampa Business College and Brewster Vocational School, both in Tampa, FL. She married her high school classmate, James D. Bruton, Jr. in 1932. The couple made their home in Plant City where they accomplished much for the community. Quintilla’s pioneering role in creating a public library for Plant City led her to be affectionately known as “The Library Lady.”

Quintilla Geer Bruton’s contributions to libraries, archives, and local history are still felt and appreciated in Plant City, Hillsborough County, and throughout Florida today. Bruton was instrumental in founding the community’s public library. The Plant City Woman’s Club held their meetings in the Miller House in Plant City. From 1927 to 1959, the volunteers gathered books and ran a community library from their meeting space where residents could check out items for a fee. The city government contributed $25 per month beginning in 1940. In 1959, the library space in the Plant City Woman’s Club facility became infested by termites and needed to be destroyed. The Plant City Woman’s Club, and Quintilla Geer Bruton in particular, were not satisfied with the space, collections, and services currently being provided to the residents in lieu of a proper, municipal library. Bruton launched a movement within the community for a government-funded, public library. In response, the city commission held an election to determine if the residents of Plant City supported a new tax to fund the creation of a municipal library. The residents voted to tax themselves in exchange for a public library, those in favor winning nearly 75% of the votes with 551 votes for and 190 votes against.

The Plant City Woman’s Club meeting site was torn down after 2,000 volumes were retained for the new library space. The Plant City Public Library was built on the same site and opened in 1960. Bruton was the 1961 winner of the annual Outstanding City of Plant City Award. The Plant City Public Library flourished. During only its third year in existence, the Library won the award for Florida’s Most Outstanding Public Library from the Book-of-the-Month Club and the Dorothy Canfield Fisher Award.

Quintilla Geer Bruton made a great contribution to the history of the Plant City area. She co-wrote the book “Plant City: Its Origin and History” with David E. Bailey. The book, published in 1985, details the history of Plant City through to 1976. Bruton was passionate about local history and preservation. She volunteered with the Daughters of the American Revolution, the East Hillsborough Historical Society, and the Community Archives Center, the latter of which is now named in her honor.

Quintilla Geer Bruton died on January 4, 1989. The Plant City Public Library was renamed the Quintilla Geer Bruton Library from 1990-1994. Her husband continued her work after her death and donated funds to support the library. In 1994, the library was renamed the Bruton Memorial Library to honor both Quintilla Geer Bruton and her husband, Judge James D. Bruton, Jr.

This post, including the image above, comes from Karmen Beecroft, Digital Projects Librarian for Digital Initiatives at Ohio University. I’ve put in a cut, so make sure you click through to read the entire post!

The eleventh of twelve children and the youngest daughter, Anne Claire Keating was born to Irish immigrant parents on February 25th, 1879 in Terre Haute, Indiana. Her father Edward, a stone mason—and “artist in marble” according to one newspaper– had arrived on American shores some eighteen years previously, at the beginning of the Civil War.(1) In Missouri, he met and soon married Ellen Cadden, herself a childhood transplant from the Emerald Isle. Half of Ellen’s children would die in the coming decades, but stalwart Anne seldom left her mother’s side.

Then known as Anna, Keating graduated Terre Haute High School in 1897 and immediately enrolled in the nearby Indiana State Normal School, which she attended until 1899. At the turn of the century, she dropped out to become Second Assistant Librarian under the direction of Arthur Cunningham, founder of the Normal School library. In 1901, Keating received a promotion to first assistant librarian, a position she would continue to hold for another two decades—minus a leave of absence from September 1907 to June 1908 to complete her library science degree at the Pratt Institute in New York. During that period, she lived in a Brooklyn boardinghouse while also attending the Brooklyn Institute as a “special student.” Her married sister Margaret lived nearby, helping her settle in and attending her when a sudden “nervous affection” which “made it painful for her even to dress her hair” kept her out of school for two days.(2) In the coming years, the two would several times vacation together on the coast for extended periods in service to Keating’s health.

Upon completing her degree, Keating returned to her parents’ home in Terre Haute, which she also shared with her widowed sister Mary. Her father and eldest brother both died in 1913; the three women moved out of the family home soon after. As president of the Terre Haute Women’s Club and patroness of the Alpha Section of the Normal School Women’s League, Keating frequently made the local papers while promoting educational lectures and mentoring her younger sorority sisters. At the library, she assumed the duties of cataloger during a period of great expansion while somehow also finding time to pursue graduate coursework at the University of Wisconsin. A satirical student publication issued around this time sketches the scene at the Normal School library in a few lines:

Misses Marshall, Keating, Darrow and Brown,

Cunningham’s satellites, and ne’er do they frown;

Four good varieties, thick, fat, and thin;

At five o’clock, mornings, their work it begins.(3)

At the age of 42, it seemed as though Keating had finally gotten her big break when a position opened up as head of the Muncie branch of the Normal School library. “I anticipate a very pleasant time at Muncie,” she told the Terre Haute Saturday Spectator. However, Keating’s mother died while preparing to make the move, derailing her ambitions; Keating remained in Terre Haute. Four years later, another opportunity for advancement arrived hand-in-hand with personal tragedy. In January 1925, her six-year-old niece Frances, of whom she had partial custody, developed acute laryngitis while in her aunts’ care and died suddenly. Several months later, Keating, then 46, left her family and hometown to assume the position of Ohio University Librarian in the small Appalachian town of Athens, some 350 miles east of Terre Haute.

Keating, the university’s third Librarian and the first woman to fill that role, arrived at Athens with an agenda. The Green and White, Ohio University’s student newspaper, reported that

the very smell of the paint and varnish used in the library redecoration attests to the initiative and leadership of the new librarian. Several changes in location and library procedure have already been announced, and are now being planned and executed. Stacks privilege[s] to be granted to students soon[; this] comes from Miss Keating’s effort to make the library more useful and attractive.(4)

Keating immediately embarked upon an ambitious remodeling plan for the crowded Carnegie Library, including “a new reference room and more commodious reading room,” as well as “a better and more complete children’s room.” In 1925, Keating’s charges numbered just 50,000 books and four assistants.

Echoing her Terre Haute occupations, Keating swiftly moved to embed herself in the Athens university culture, becoming first secretary and later president of the OU chapter of the American Association of University Women. A dedicated patroness of the Theta Phi Alpha sorority, she often collaborated with popular Dean of Women Irma Voigt to facilitate student programming and provide mentorship. An enduring autodidacticism led Keating to pursue a fifth course of study at George Washington University and by 1931 she had added a Bachelor of Arts degree to her ever-growing portfolio.

1931 also saw the completion of the Edwin Watts Chubb Library and the transfer of the Carnegie stacks—now housing 70,000 volumes—to the new building. Chubb Library provided space for some 240,000 books and 600 simultaneous readers, a threefold increase over the study space available at Carnegie. Head counts conducted by Keating’s staff revealed that the new library received 20,000 visits a month during the opening years of the Great Depression, a great increase over usage patterns observed in the 1920s. The incoming university president Herman James dealt the Library’s newfound popularity a blow, however, when he directed that Keating’s decade-long open stacks policy be discontinued. “It is felt that lower classmen are not ready for undirected browsing among so many volumes,” Keating reservedly reported to The Green and White. “They must first be educated for this responsibility.” (5) The closed stacks mandate proved extremely unpopular in subsequent years, though Keating noted in exasperation that only half the senior class ever reported to receive their passes. Nevertheless, she continued to remove barriers when able, adding a fiction-heavy open shelf collection just a semester after James’ announcement.

In 1937, Keating returned to her Normal School roots with the development of a 3-credit course for prospective educator-librarians. Keating tartly noted that her class—the first in school library administration offered by a state university in Ohio– “in no sense prepares the student for full time librarianship.”(6) Though enrollment varied, Keating continued to offer the course for twelve years until her retirement in 1949 at the age of 70.

Over the 24 years of her tenure at OU the student body as a whole grew 400%. Keating reacted by growing the collections to 180,000 volumes and increasing her staff to 12 assistant librarians and three clerical assistants. An army of fifty student workers sprang up to deal with the closed stacks system and increased circulation. Keating’s retirement coincided with that of Dean Voigt, her longtime collaborator. The Ohio Alumnus hinted at intriguingly unspoken controversies during their long careers: “both women were in positions in which it was impossible to please all person having dealings with them. There are doubtless those who do not agree with some of their actions and decisions. But, many fewer, we’ll warrant, is the number who do not credit them with an earnest desire to deal fairly in the matters within their wide jurisdictions.”(7)

Upon quitting Athens, Keating joined her sister Margaret in Croton-on-Hudson, New York, until Margaret’s death in 1952. At the age of 73, Keating returned for a last time to Terre Haute to live with her widowed sister-in-law Clara. A few months later, Keating herself died of heart disease. From “Cunningham’s satellite” to university administrator, Anne Keating’s life is one of conflicting drives and stymied ambitions finally realized. As an unmarried daughter, her responsibilities were culturally prescribed by the needs of the family, even as her remaining family members assumed responsibility for her welfare later in life. She never let these pressures constrain her mind, however—during the 26 years she served at the Normal School library, she pursued coursework through three different universities and sought continually to further her education through reading and lectures. At Ohio University, her evenhanded management saw her library safely through the Great Depression and World War II. Though she personally disliked publicity, “Miss Keating’s” legacy is indeed a very public one—the modern library system she founded, with its emphasis on pedagogy and usability, forms the basis of our institution today.

Notes

1 Terre Haute Saturday Evening Ledger [Terre Haute, IN] 2 April 1881: 8.

2 Terre Haute Sunday Spectator [Terre Haute, IN] 16 November 1907

3 Denehie, Elizabeth. “A Eulogy on our Faculty.” Normal Advance [Terre Haute, IN] June 1915: 309.

4 “Introducing Miss Keating.” The Green and White [Athens, OH] 9 February 1926: 1.

5 “New Library Rules Issued.” The Green and White [Athens, OH] 27 September 1935: 1.

6 The Green and White [Athens, OH] 26 February 1937: 4.

7 Williams, Clark E. “From the Editor’s Desk” The Ohio Alumnus [Athens, OH] May 1949: 2.

Emily Wagner, Information Manager in the American Library Association’s Washington Office, wrote to WoLH to highlight the work of Patricia Glass Schuman:

As the 1991-92 president-elect of ALA, Patricia Glass Schuman launched a nationwide media campaign to focus public attention on threats to the public’s right to know—including library funding cuts, censorship, and restricted access to government information—and the need to support libraries and librarians. More than 500,000 Americans called a special toll-free number or signed petitions to Congress supporting full funding for libraries. During her presidency, Schuman implemented a program of media training for ALA chapters and division leaders and founded ALA’s first Speaker’s Network. Schuman was a founding member of the Social Responsibilities Roundtable and the Feminist Task Force! And, in 2014, she was named a Lifetime Member of the association.

Emily also passed along the Washington Office’s recent blog post, “Look Back, Move Forward: Five Women Who Stood Up For the Public’s Right to Know,“ which highlights the work of Rep. Zoe Lofgren, Meredith Fuchs, Hazel Reid O’Leary, previous WoLH subject Eileen D. Cooke, and Schuman. Give it a read!

Today’s post is from Jeri Toney Davis, Huntington City Township Public Library, Huntington, Indiana, who notes that “Miss Ticer is my favorite subject.”

In the fall of 1901, three railroad men from the small town of Huntington, Indiana, travelled to New York City to meet with Andrew Carnegie with the hope of securing money to build a free standing library. Two years later, on Saturday, February 21, 1903, a beautiful, 7,700 sq. ft. Bedford stone Carnegie Library was opened to the public in grandeur style. I could say the ole cliche “and the rest is history”, but for this small town with a new library, their journey was just beginning.

In 1904, with the resignation of Miss Lyle Harter, the board decided to promote the Assistant Librarian, Miss Winifred Ticer, to the position of Librarian. Winifred was an ambitious 32-year-old single woman with plenty of ideas of her own. In the years that followed, progress was steady, with new books added and circulation numbers increasing yearly. More and more services were provided while older services were evaluated as to their usefulness.

The library came to life under Winifred’s reign. Winifred listened to the needs of women and understood they wanted more in-depth reading and activities from their library. Winifred introduced a broad range of nonfiction books as well as fiction books for the adult woman. Reading clubs for children were initiated, and reference and genealogical work became important. The library was continuously changing and evolving as the city went through its growing period. Winifred kept up with what was going on around her and kept her library up to date and inspiring for the city of Huntington. She even saw the need for growth and opened a branch library in a small room located in the school.

The Railroad and Scientific reading room was also formed under Winifred. This room contained over 600 volumes of books designed for the workingman to get all the knowledge he needed on the subject he was researching. The reading room was well received for the early 1900’s. Today we would call such a room a “career center”.

Winifred was accomplished in other areas of library work as well. Her library was the first library in Indiana to advertise in the newspaper. Soon she found herself receiving questions from other libraries about how they could advertise their own library. This prompted Winifred to write a book called Advertising the Public Library, published in 1921 by the Democrat Printing Company of Madison, Wisconsin. She also wrote poetry, titled Fellowship and Other PoemsandHill Tops and Other Poems.

In 1922, Winifred was offered a job at the Democrat Printing Company, the same company that published her book. That company today is known as Demco. She stayed at the Democrat until 1929, then moved to Ohio to take a job with Warren Public Library. Winifred retired from the Warren Public Library in 1949 at the age of 77. She passed away in 1964 at 92.

I have only given you a small glimpse into the world of Winifred Ticer. She was ahead of her time in how she viewed libraries and their purpose. The library was more than a brick and mortar building to her. She felt the library had something to offer for everyone and she made sure everyone knew it. Huntington, Indiana, will forever be a better place because of her.

Reference: Huntington City Township Public Library history scrapbook - Indiana Room Archives, Warren -Trumbell County Public Library of Ohio

Jessamyn West suggested that we repost the Wikipedia article about Jewell Mazique, which she (mostly) wrote. She adds, “Ms. Mazique was notable for her activism regarding racism, labor history and international cooperation. She was also photographed as part of the Office of War Information’s attempt to show Americans how their way of life was “worth fighting for” and there are many photographs taken of her when she was a clerk at the Library of Congress in the 40s.” The photos, which are in the public domain, include images of Mazique at work, speaking at church, giving blood, reading, and spending time with her family.

Jewell R. Mazique (2 October 1913 - 18 September 2007) was an activist who helped found the Capital Transit campaign with United Federal Workers to integrate Washington D.C.’s bus operators.[2] [3] Mazique wrote extensively for The Washington Afro-American newspaper on topics such as the United Nations position on African Nations, and how black children were being educated in DC schools.[4] She served on the National Council for the Southern Negro Youth Congress in 1945, a group claimed to be a Communist front organization. [5]

She was the subject of a U.S. Government Office Of War Information documentary photo series in 1942 while she was a clerk at the Library of Congress.[6] The photos, taken by John Collier, were supposedly depicting a day in the life of a typical black Washingtonian but critics argued the photos were “less picturesque and less a credit to freedom’s national seat” than a typical day of an average black woman in Washington D.C. [7]

Mazique graduated from Spelman College and received a Masters in African Studies from Howard University where she wrote her thesis on the development of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. [8] [4] Mazique argued her own acrimonious divorce case despite the court’s requests to take legal counsel. She kept her children, but lost her case for personal financial support.[9]

Personal life

Mazique was married to Edward Craig Mazique in 1937, separated in 1961, and divorced in 1965.[10] [11] They had two sons, Edward and Jeffrey.[2] Edward was the first black child to attend kindergarten at the Sidwell Friends School in 1956. As a direct result, Senator James Eastland, an anti-integrationist from Mississippi, withdrew his son from the school. [4]:49

Jewell Mazique preferred to be involved with social causes more than having a social life, stating in an interview, “The frills of social life hold no charms for me, I am more concerned for instance with what the political leaders of Paris decided to do about their colonial possessions than what the Paris designers decide about what women will wear. [4]

Divorce

Mazique decided that her marriage to Edward could not continue although she did waver in her decision. Eventually Edward started divorce proceedings on the grounds of desertion. Mazique hired a number of lawyers before she decided that she could do a better job herself. The divorce was very public and at one point Jewell’s friends appeared with placards outside the Park Sheraton Hotel in Washington in support of her divorce case. The location was chosen as Marguerite Belafonte had a fashion show there and she was seeing Edward Mazique. One placard read "Let not justice be rationed to Jewell R. Mazique in the Domestic Relations Court”. Jewell’s friend wrote to the newspapers and they formed a committee to support her.[12] The case was settled in her husband’s favour and it was noted that Jewell had argued her own case despite the court’s advice. She argued, unsuccessfully, that she had worked to put her husband through medical school and that the court had ignored their expensive home.[10] Jewell appealed the case and particularly the finances arguing that the court was biased toward men. She lost the appeal in 1965. Mazique kept her children and Edward agreed to pay maintenance, but she lost her case for personal financial support. The court ruled that her case was a fabrication.[9] Both of her sons went on to be physicians.[12]

References

From the Desk of Gratia Countryman

Here is the first in an ongoing series from the desk of Gratia Countryman. Gratia Countryman was very important to the history of Hennepin County Library. She was the director of Minneapolis Public Library for over 30 years and she founded Hennepin County Library.

This is from Ms. Countryman’s annual report from the first year of her administration, 1904:

What is a library for?

A public library is the one great civic institution supported by the people which is designed for the instruction and pleasure of all people, young and old, without age limit, rich and poor, without class limit, educated and uneducated, without culture limit. Its function being to instruct and benefit, how are we going to accomplish this end? In the opinion of your librarian there is positively no limit to the things which a public library can legitimately do in carrying out its purpose, except the limitations of financial resources. It should be “all things to all men” in the world of thought, by keeping in close touch, not only with the leaders of thought, but with the rank and file of the people. This will mean many forms of activity which in the past were not connected with the idea of a library. Perhaps still in the minds of many a library is only a place where books are stored, or distributed under many objectionable restrictions. But in the larger sense, the library should be a wide-awake institution for the dissemination of ideas, where books are easily accessible and readily obtainable. It should be the center of all the activities of a city that lead to social growth, municipal reform, civic pride and good citizenship. It should have its finger on the pulse of the people, ready to second and forward any good movement. It should be the home of clubs and societies and free lecture courses. …gracious and sympathetic hospitality should be the prevailng spirit of the place, and every member of a well disciplined staff will need, not only a broad education, but the most genuine willingness to serve.

How to reach the busy men and women…how to enlist the interest of tired factory girls, how to put the workingman in touch with the art books relating to his craft and so increase the value of his labor and the dignity of his day’s work - these are some of the things which I concieve my duty to study, if I would help this public library to become what it is for.

Gratia Countryman, Librarian

Kellian Clink (Minnesota State University, Mankato) and Kaia Sievert (University of Minnesota) both got in touch this year to sing the praises of legendary Minnesota librarian Gratia Countryman. Bailey Diers (Hennepin County Library) helped point out HCL’s wealth of online resources about Countryman, including a whole series of Tumblr postsanda significant collection of digitized photos.

Her life and career are pretty amazing (quoted from this post):

Read the whole post for more about her career, the son she adopted, and the homes she built and lived in with her colleagues (one of whom, Marie Todd, was her life partner and a co-parent to her son).Gratia Alta Countryman was born November 29, 1866, in Hastings, Minnesota, the daughter of pioneer parents Levi and Alta Chamberlain Countryman. […] In 1904 she succeeded Hosmer as chief librarian, becoming the nation’s first female head librarian. Countryman was chief librarian for over thirty-two years until 1936 when she was required to retire at the age of seventy. She was then made librarian emeritus.

Upon Countryman’s promotion to chief librarian she immediately began to make changes, expanding the Library’s services to reach more and more people. In the thirty-two years she directed the Library, service expanded into all areas of the city including elementary and junior high schools, hospitals, engine houses, welfare centers, and factories. By the time of Countryman’s retirement, the book collection had increased to 662,842 volumes and the circulation, which was 519,000 in 1904, had increased to 3,293,484 in 1936. The number of registered borrowers had increased from 40,500 in 1904 to 181,582 in 1936. Of the 11 branch library buildings in Minneapolis, 9 were built during her administration. Countryman was instrumental in local, state, and national library work, and was elected President of the American Library Association from 1933-34 becoming the sixth woman to hold that distinction in the association’s hitherto sixty year history.

Post link

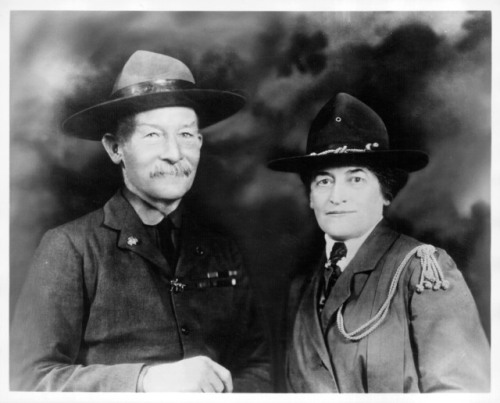

March 12th 1912: The Girl Scouts founded

On this day in 1912, the Girl Guides - who would later become the Girl Scouts of the USA - were founded. The organisation was founded by Juliette Gordon Low, after she met the founder of Scouting - Robert Baden-Powell. The first Girl Scout meeting took place on March 12th in Savannah, Georgia, with 18 girls attending; there are now over 3.2 million members. Low wanted to give America and the world “something for the girls” and aimed to encourage girls to become active citizens and to develop their full potential. They soon became an important group in the USA, with Martin Luther King Jr describing the Girl Scouts as “a force for desegregation” in the 1950s and 1960s.

“I’ve got something for the girls of Savannah, and all of America, and all the world, and we’re going to start it tonight!”

- Juliette Low at the first Girl Scout meeting

Post link

Happy International Women’s Day!

(I know that this is late, sorry)

Spotlight here is on Idawalley Zorada Lewis-Wilson AKA Ida Lewis, an American lighthouse keeper who saved people from the seas!

My Ko-fi page: ko-fi.com/benesumi

Post link

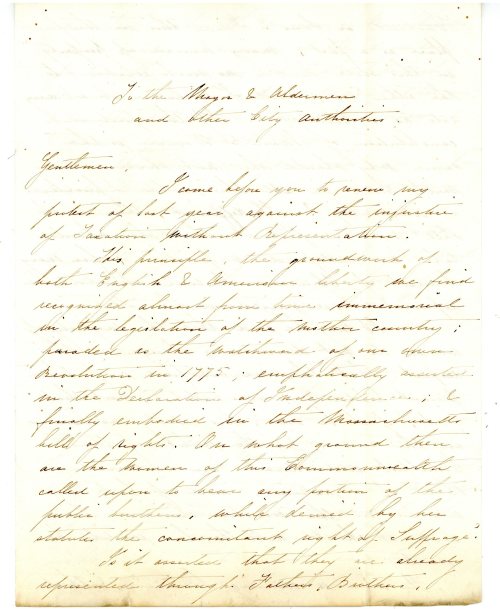

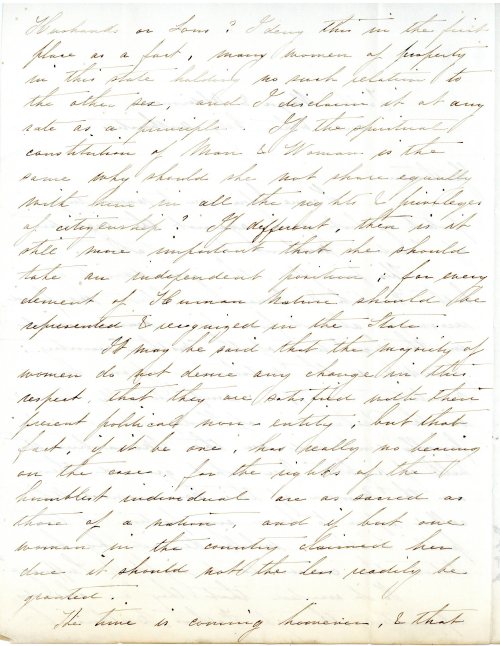

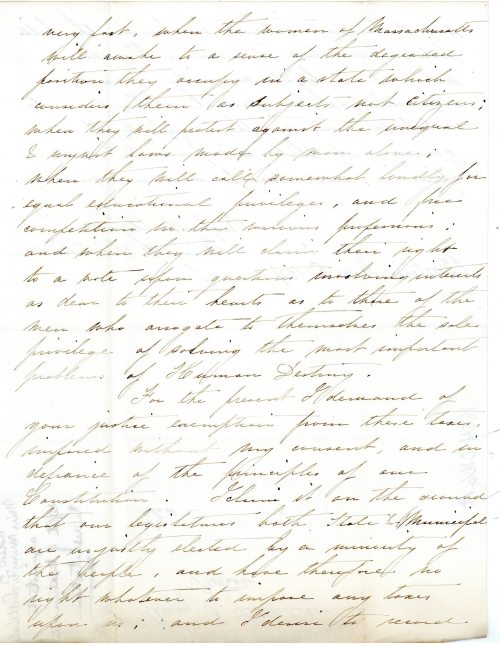

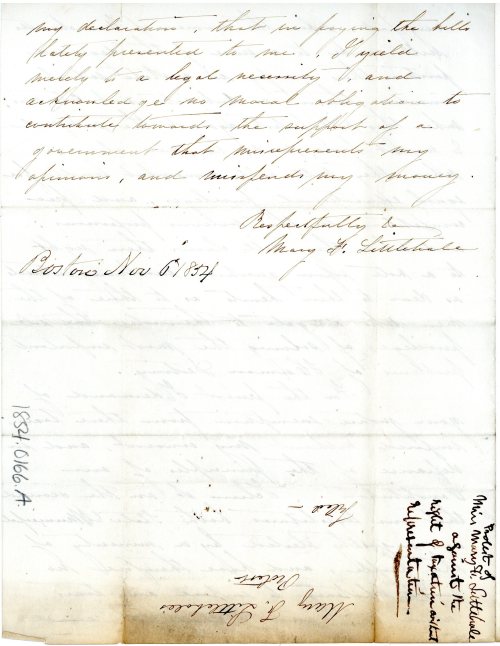

On this day in 1854, Mary Littlebale wrote to Boston’s Board of Aldermen to protest against the “taxation without representation” of Massachusetts women.

Littlebale argued that the practice of taxing women who could not vote flew in the face of the principles laid out in the Declaration of Independence as well as the Massachusetts Bill of Rights. She wrote “On what ground are the women of this Commonwealth called upon to bear any portion of the public burden while denied by her statues the concomitant right of Suffrage?”

After arguing against common arguments against women’s suffrage, Littlebale ended her letter, “I demand of your justice exemption from these taxes enforced without my consent and in defiance of the principles of our Constitution.”

We know that LIttlebale’s letter was received by the Board of Aldermen and filed, but we don’t have any record of their response to her. Women in Massachusetts did not gain full suffrage until 1920. Read her entire letter above.

Docket 1854-0166-A Proceedings of the City Council, Collection 0100.001, Boston City Archives .

Post link

This morning’s image is a 1914 lantern slide showing a student at Girls Trade School practicing dress fitting. Students at Girls Trade practiced dress fitting on fellow students and on dolls.

For more lantern slides from Girls Trade, click here

“Showing how the little folks were fitted and dressed by Junior dressmakers.” circa 1914, Trade School for Girls lantern slides, Collection 0420.041, Boston City Archives, Boston

Post link

Աշխեն Հովակիմյան

Ashkhen Hovakimian

Anglicised toAgnes Joaquim. She was an Armenian woman who bred the world’s first cultivated orchid hybrid, Vanda ‘Miss Joaquim’. This flower was chosen on 15th april 1981 as the national flower of Singapore, for it’s resilence and year-round blooming quality, ment to represent Singapore’s uniqueness and hybrid culture. Joaquim was inducted in the Singapore Women’s Hall of Fame in 2015.

Ashkhen was the eldest daughter to Basil, her father who was an Armenain merchant and commercial agent and her mother Urelia, also an Armenian who was an avid gardener. Ashkhen joined in with her mothers interests as well as being an active member of the Armenian Church. She was also a very skilled embroiderer.

Agnes lived a very short life, dying only at the age of forty five. She managed to achieve very much in her short life. Winning prizes annualy at flower shows and won the prize of the rarest orchid at the 1899 annual flower show. Shortly after she died from cancer. Her flower was used as symbols for various organizations, societys and political parties. In april 1981 came the ultimate honour, from from forty contenders, her flower was selected as the national flower of Singapore.

Her family members were also highly successful. Narcis street in Singapore is named after her brother Nerses. Her Brothers Jonathan and Robert were well known barristers and founders of the legal Company Braddel Brothers. Another brother of hers Arathoon was the Deputy registrar of the Hacnkey Carriges Department. Ashkhens grandniece also cultivated famous flowers. Also Ashkhens maternal grandfather was the first member of the Singapore Chamber of Commerce, They are all a small part of the unique Armenian community of Singapore.

Post link