#ww1 centenary

A Belarusian cartoon lamenting the partition of Belarus between the Soviets and the Poles in the Treaty of Riga; note that the original Soviet proposals would have placed MInsk (center) on the Polish side.

March 18 1921, Riga–The Soviets and Poles had concluded an armistice in October, but a formal peace treaty had proved elusive. The Soviets, eager to normalize their relations with their neighbors, were fine with drawing the border roughly along the armistice line. Many of the Polish negotiators, however, did not want to annex so much eastern territory whose inhabitants were mostly Belarusians and Ukrainians, and the Polish delegation rejected the offer, much to Piłsudski’s chagrin.

By March, Lenin, who had other more pressing internal concerns with Kronstadt, strikes, and peasant unrest, pressed for a resolution to the negotiations, and on March 18 a treaty was signed in Riga. A border was agreed to about 60 miles west of the original Soviet proposal (but still around 150 miles east of the modern Polish frontier). Most notably, this meant that Minsk would return to Soviet hands. Poland would also receive 30 million rubles in compensation for Russia’s hundred-year occupation of the country.

The deck of the Petropavlovskafter the defeat of the rebellion.

March 17 1921, Kronstadt [Kotlin]–The failure of the initial attack on Kronstadt was an embarrassment for the Communists, who on the same day convened their Tenth Party Congress in Moscow. On March 10, after Trotsky reported on the situation, 320 delegates volunteered to join the fight. With the spring fast approaching and the ice in the Gulf of Finland threatening to melt, Tukachevsky had to act quickly.

While he prepared another offensive, events moved even quicker at the Congress in Moscow. Lenin had found himself facing direct threats from Kronstadt, strikes in the major cities, and widespread peasant rebellions, along with internal opposition in the form of the Alexander Shliapnikov and Alexandra Kollontai’s Workers’ Opposition. The strikes had largely petered out by mid-March, with promises that trade would resume with the countryside and the food situation would improve. Kronstadt would be crushed by force. The Workers’ Opposition would be effectively dissolved by a ban on internal Communist Party factions, passed without fanfare on April 16 but which would confirm a dictatorship until Gorbachev.

The farmers, Lenin chose to mollify. Food had heretofore been requisitioned from communities in large quantities by the government. This system was to be turned into a tax, 45% lower than the previous rate, and levied on an individual basis. Any remaining food could be sold on the open market, and additional incentives were provided to boost production. What would become the New Economic Policy pleased the farmers who directly benefited, and the city-dwellers whose food worries would be alleviated; it had only taken a betrayal of Communist ideals. Lenin justified this before the Congress on March 15 by saying that an alliance with the peasants was needed if Communism was to survive in a relatively non-industrialized country like Russia without outside help–but after years of war, there was little opposition to a policy that might bring an end to the conflicts.

The announcement of the land tax also boosted the morale of Tukachevsky’s forces, which had also been reinforced with loyal Communists from around the country. He began another bombardment of Kronstadt on the afternoon of the 16th, and his infantry attacked across the ice in the wee hours of the 17th. Casualties were high; over 10,000 (including 15 of the party delegates who had volunteered from Moscow) were felled by the defenders or were lost through holes in the ice. But shortly before midnight, the Communists had captured the Petropavlovskand most of the other rebellious ships. About 8000 of the rebels escaped across the ice to Finland; most of those captured by the Communists were shot or died in a concentration camp on the White Sea.

Sources include: Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy; W. Bruce Lincoln, Red Victory.

Soviet and Turkish signatories of the Treaty of Moscow.

March 16 1921, Moscow–TheSoviet invasion of Georgia brought Soviet Russia into direct contact with Turkey, which soon thereafter invaded the country from the south. The Soviets had already repudiated the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk that had given up large areas to the Ottoman Empire. Kemal’s government in Ankara wanted to keep these gains, but was also diplomatically isolated and was more worried about the Allies occupying Constantinople and Smyrna.

On March 16, representatives from Kemal’s government and the Soviets signed a treaty in Moscow. Turkey got to keep most of the gains from Brest-Litovsk, with the exception of Batum [Batumi], while Turkey recognized the Soviet republics in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia. Both sides repudiated Brest-Litovsk and Sèvres, and the question of navigation of the Straits was deferred to a later time. Residents of the territories Russia gave up in Brest-Litovsk were to have the right to leave Turkey with their property intact. Azerbaijan’s control over the Nakhchivan exclave, which continues to this day, was confirmed by both sides.

The treaty brought an end to Turkey’s adventures in the Caucasus (for many decades), and the borders established by the treaty remain largely unchanged to this day. The last organized Georgian resistance to the Soviet invasion collapsed two days after the treaty, leaving the Soviets free to concentrate on the Dashnaks in Armenia.

Sources include: Evan Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War

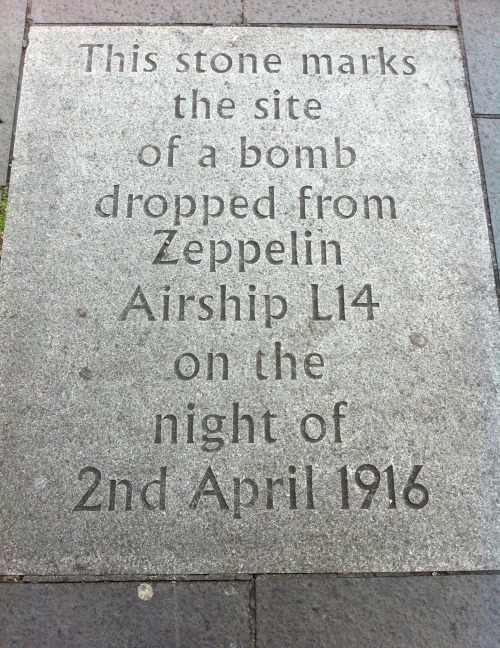

Centenary of Edinburgh Zeppelin Raid

Tonight marks 100 years since two Imperial German Zeppelins attacked Edinburgh and Leith resulting in the deaths of 13 people and injuring 24 others.

On the night of the 2nd April, 1916 four Zeppelins set out from the German Naval Airbase base of Nordholz with the intention to find and destroy targets of interest in and around the Firth of Forth especially the large Naval facilities of Rosyth. One of the Zeppelins, L13 was forced to turn back due to technical difficulties whilst L16 made an abortive journey to Northumberland.

The remaining two Zeppelins: L14 and L22 approached Leith and Edinburgh. L22 caused minor damage to Edinburgh having jettisoned much of its payload in open country near Berwick-Upon-Tweed. L14 however made a sustained attack on both Leith and the Scottish Capital. In Leith nine high-explosive bombs and eleven incendiary bombs were dropped on the town destroying several houses, businesses and warehouses. One man and a baby were killed.

L14 then continued on to Edinburgh were a further 18 high-explosive bombs and six incendiary bombs were dropped killing 11 people and injuring a further 24 others. Four houses, three hotels and a spirits store were severely damaged with Princes Street station and several other building sustaining lighter damage.

The images included are as follows:

i – The memorial pavement stone situated in the centre of Grassmarket in front of the White Hart Inn which was devastated in the 2nd April raids.

ii – The devastated Grassmarket buildings which includes the White Hart Inn.

iii – A close up of the White Hart Inn.

iv – Zeppelin L14

Post link

The poppies at The Tower of London. A staggering 888,246 poppies will eventually appear in the grounds of the Tower - one for every soldier from the UK, Australia and the Commonwealth killed during the Great War

Post link