#russian civil war

April 2 1921, Yerevan–TheSoviets took over most of Armenia in December 1920, seeming a better alternative to the approaching Turkish armies. Soviet control was short-lived, after the Soviets quickly alienated much of the population, the Dashnaks were able to retake Yerevan and much of the surrounding area in mid-February. After conquering Georgia and negotiating a peace treaty with the Turks in March, the Soviets were once again able to concentrate on Armenia, launching an offensive on March 24 and retaking Yerevan on April 2. The Dashnaks fell back into the mountains in the Syunik province, where they continued to fight against the Soviets until July.

The deck of the Petropavlovskafter the defeat of the rebellion.

March 17 1921, Kronstadt [Kotlin]–The failure of the initial attack on Kronstadt was an embarrassment for the Communists, who on the same day convened their Tenth Party Congress in Moscow. On March 10, after Trotsky reported on the situation, 320 delegates volunteered to join the fight. With the spring fast approaching and the ice in the Gulf of Finland threatening to melt, Tukachevsky had to act quickly.

While he prepared another offensive, events moved even quicker at the Congress in Moscow. Lenin had found himself facing direct threats from Kronstadt, strikes in the major cities, and widespread peasant rebellions, along with internal opposition in the form of the Alexander Shliapnikov and Alexandra Kollontai’s Workers’ Opposition. The strikes had largely petered out by mid-March, with promises that trade would resume with the countryside and the food situation would improve. Kronstadt would be crushed by force. The Workers’ Opposition would be effectively dissolved by a ban on internal Communist Party factions, passed without fanfare on April 16 but which would confirm a dictatorship until Gorbachev.

The farmers, Lenin chose to mollify. Food had heretofore been requisitioned from communities in large quantities by the government. This system was to be turned into a tax, 45% lower than the previous rate, and levied on an individual basis. Any remaining food could be sold on the open market, and additional incentives were provided to boost production. What would become the New Economic Policy pleased the farmers who directly benefited, and the city-dwellers whose food worries would be alleviated; it had only taken a betrayal of Communist ideals. Lenin justified this before the Congress on March 15 by saying that an alliance with the peasants was needed if Communism was to survive in a relatively non-industrialized country like Russia without outside help–but after years of war, there was little opposition to a policy that might bring an end to the conflicts.

The announcement of the land tax also boosted the morale of Tukachevsky’s forces, which had also been reinforced with loyal Communists from around the country. He began another bombardment of Kronstadt on the afternoon of the 16th, and his infantry attacked across the ice in the wee hours of the 17th. Casualties were high; over 10,000 (including 15 of the party delegates who had volunteered from Moscow) were felled by the defenders or were lost through holes in the ice. But shortly before midnight, the Communists had captured the Petropavlovskand most of the other rebellious ships. About 8000 of the rebels escaped across the ice to Finland; most of those captured by the Communists were shot or died in a concentration camp on the White Sea.

Sources include: Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy; W. Bruce Lincoln, Red Victory.

Bolshevik forces attack across the ice towards Kronstadt.

March 8 1921, Kronstadt–The call for a partial democratization of the soviets by the sailors of the Kronstadt naval base was treated as a mortal threat to the revolution by the Bolsheviks in Moscow. Trotsky was sent to Petrograd, issued an ultimatum to the sailors, and took whatever family members he could find as hostages. On March 7, Bolshevik artillery began firing on Kronstadt, and on the wee hours of March 8, under cover of a snowstorm, infantry under Tukhachevsky attacked across the ice. It was worried that their loyalty was shaky, so behind them were Cheka and specially-picked units to make sure they did not flee. To the south of the island, artillery from Kronstadt blew holes in the ice and many of the attacking infantry fell into the freezing water. Some reached the island in the north, but were outnumbered and quickly repulsed.

On the morning of March 8th, the fourth anniversary of the start of the February Revolution, the sailors on Kronstadt were able to celebrate a victory over the Bolsheviks. Their own version of Isvestiapulled now punches in a statement that day:

By carrying out the October Revolution the working class had hoped to achieve its emancipation. But the result has been an even greater enslavement of human beings. The power of the monarchy, with its police and its gendarmerie, has passed into the hands of the Communist usurpers, who have given the people not freedom but the constant fear of torture by the Cheka, the horrors of which far exceed the rule of the gendarmerie under tsarism…

Sources include: Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy; W. Bruce Lincoln, Red Victory.

March 1 1921, Kronstadt–Aside from the distant reaches of the Far East, the Whites had been defeated, but severe threats to Bolshevik power remained and even intensified. Revolts spread across the countryside after a poor harvest added to years of hardship from Bolshevik grain requisition. In the cities, hunger became a major concern; by late January, the food ration provided to workers in Moscow and Petrograd was down to 1000 calories a day. Large strikes broke out in Moscow on February 21 and Petrograd the next day, calling for the reconvening of the Constituent Assembly, freedom of movement (most critically, the freedom to go into the countryside and trade for food there, a pattern that had become very familiar in Russia and Germany during the war) and other rights that had been denied by the Bolshevik government. The parallels with the final days of the Czar were undeniable.

The unrest soon spread to the Kronstadt Naval Base, whose sailors had been in the vanguard of leftist opposition to the Provisional Government in 1917. On February 28, the crew of Petropavlovsk,historically staunch Bolsheviks, issued a proclamation calling for new elections for the soviets, full political freedoms for workers, peasants, left socialists and anarchists, and allowing peasants to manage their own land as they see fit as long as they do not hire labor. The proclamation was undeniably left-wing (unlike the strikers in the city, they notably did not call for the Constituent Assembly), but was a clear call for democratization of the Soviets (albeit with participation still extending no further right than the left SRs) and an end to the Bolshevik dictatorship.

On March 1, a crowd of 15,000 met in Anchor Square and agreed for new elections to the local Soviet. The Bolsheviks sent Kalinin to try to defuse the situation, but he only attracted jeers. The next day, rightfully worried that the Bolsheviks would quickly try to take action against them, a Revolutionary Committee of five was elected to organize elections and a defense of the island.

Sources include: Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy; W. Bruce Lincoln, Red Victory.

Soviet forces on parade in Tblisi on February 25.

February 25 1921, Tblisi–With both AzerbaijanandArmenia now under Soviet control, the the Soviets quickly turned their attention to Georgia, which was still under control of a Menshevik-dominated government. On February 12, local Bolsheviks began attacking the Georgian military. Two days later, Lenin agreed that the Red Army should intervene, after repeated urging from Stalin, himself a Georgian. On February 16, the Red Army crossed into Georgia, and after an intense nine days of fighting, Soviet tanks (captured from the Whites and their British allies earlier in the Civil War) and armored trains broke through the defenses in the heights above Tblisi.

On February 25, the Soviets entered the city and the local Bolsheviks declared the establishment of the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic. The fall of Tblisi did not mark a complete Soviet victory in the Caucasus, however. Georgian forces, although quickly losing cohesion, were falling back towards the coast and Batum [Batumi]. Simultaneously, the Turks had taken advantage of the situation by seizing some disputed border areas, and they had their eyes on Batum as well. Meanwhile, in Armenia, nationalists had revolted against the Soviets and seized control of Yerevan.

Soviet troops entering Yerevan on December 4.

December 2 1920, Yerevan–Since the Turkish invasion in September, the Armenians had repeatedly suffered defeats. By the time a ceasefire was concluded in mid-November, they had lost most of their territory and faced a choice between a humiliating peace reducing them to a rump state around Yerevan, or complete annihilation. A few days later, the Soviets decided to take advantage of the situation and invaded the country. Ultimately hoping that Soviet backing might improve their position against the Turks, the Armenian government resigned in favor of local Bolsheviks on December 2; Soviet troops entered the city two days later; they would not leave until 1991.

White soldiers on board one of the ships leaving the Crimea.

November 14 1920, Sevastopol–The Soviets had launched what they hoped to be their final offensive against Wrangel in late October. Although they destroyed much of his army, enough of it was able to fall back to the narrow isthmus connecting Crimea to the mainland to mount a concerted defense. This, however, was overcome by direct and amphibious attacks between November 7 and 11, and it became quickly apparent that Crimea would soon be lost.

Wrangel had been preparing for such a possibility since his arrival in the spring, however, and he was much better equipped than Denikin had been when evacuating the Kuban in March. Wrangel left Sevastopol on the 14th, and simultaneous evacuations took place at at least four other Crimean ports. 146,000 White soldiers and refugees were taken across the Black Sea to Constantinople by the end of the evacuation efforts on the 16th, aided by a one-day pause by regrouping Soviets.

Those who did not or could not evacuate, however, met a grimmer end. Béla Kun was put in charge of Soviet administration in the area. The Cheka killed tens of thousands in the coming weeks. In Kerch, “trips to the Kuban” were organized: prisoners were taken out into the Sea of Azov and pushed overboard to drown.

Those who evacuated were interned and then lived in exile. Wrangel took with him the last of the Blask Sea Fleet, including the dreadnought General Alexeyev, were interned in French Tunisia until the French recognized the Soviet Union in 1924.

Sources include: Evan Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War; W. Bruce Lincoln, Red Victory.

October 28 1920, Kakhovka–As the war against Poland wound down (ending in an armistice in mid-October), the Soviets had been moving forces south to deal with the last major White force opposing them, Wrangel’s troops in North Taurida and Crimea. On October 28, Budyonny’sKonarmia broke out from the Kakhovka bridgehead, hoping to cut off the rail lines between Wrangel’s forces and their refuge in Crimea. Wrangel had known he was in danger of being cut off, but had kept his forces in North Taurida to secure food from the harvest in that area. Soviet infantry also advanced across the Dnepr and pushed south at a slower pace.

The offensive did force the surrender of well over half of Wrangel’s forces, but within five days, the remaining portion (including his most experienced troops) had managed to escape into Crimea, exactly what Frunze had feared. Wrangel was still in firm control of Crimea, and the situation was much the same as it had been in the spring–just without the looming threat of a war with Poland.

Sources include: Evan Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War.

October 16 1920, Riga–After defeats on the Vistula and the Niemen, the Soviets were ready to sue for peace with Poland before losing any more territory. Likewise, Poland had learned their lesson from their misadventures in Ukraine earlier in the year, and wanted peace from a position of strength, without overextending themselves too far once again. On October 12, the Poles and Soviets agreed to an armistice. However, it would not go into effect for several days, and both sides spent the last few days of fighting securing as much territory as they could, as the armistice line could very well determine the ultimate negotiated frontier. The Poles still had the upper hand here, and on October 15 they captured Minsk from the Soviets. The ceasefire entered into general effect on the 16th, though limited fighting continued until the 18th in some areas.

The ceasefire, however, did not apply to Poland’s allies–Petliura’s Ukrainians and smaller forces of Belarusians and Whites. However, these forces found themselves highly outnumbered without explicit Polish support, and these groups were largely defeated and forced into exile by the end of November.

October 6 1920, Kakhovka–Sincebreaking out of Crimea in early June, Wrangel’s front had largely stabilized, covered by the Dnepr in the north (excepting a Soviet bridgehead established around Kakhovka in August). Attempts to land in the Kuban and reconnect with Denikin’s old power base among the Cossacks there had failed. On October 6, Wrangel tried one final offensive, pushing north across the Dnepr. There was, at least initially, some hope that the offensive would encourage the Poles to move into Ukraine as they had earlier in the year. However, the Poles had learned their lesson in the spring and were already negotiating an armistice with the Soviets.

The Soviets, although they were desperately trying to prevent the Poles from taking territory before a possible armistice, had already begun moving troops south to face Wrangel. However, they were slow in coming–Budyonny’s Konarmiahad been wrecked by months of fighting, culminating in their near-destruction at Komarów, and it would take them nearly a month to move south. They still managed to find time to conduct pogroms on the way, however.

As a result, Wrangel’s forces were able to cross the Dnepr and make limited progress. However, even without the incoming reinforcements, the Soviets still outnumbered the Whites, and Wrangel’s troops had to withdraw back across the river within a week. It would be the last major White offensive in the civil war.

Sources include: Evan Mawdsley, The Russian Civil War

Semyon Budyonny and Kliment Voroshilov after the capture of the city of Rovno.

Photographer: Petr Adolfovich Otsup, 1919.

Fighters of the working battalion, engineer V.P. Ivanov and metro driver D.S. Dyachkov.

Moscow militia.

Nikolai Konstantinovich Marshalk (1895 - 1951)

Since 1918 he was in the Volunteer Army (White army) and participated in the Ice March. He was serving as Second Lieutenant in the Kornilov shock division, and was wounded twice. In 1919 he returned to his homeland Latvia but was enlistend in the North-Western Army the same year. In December 1919 he transfered to the Rifle Division of the 5th Infantry Division. He survived the civil war and emigrated to Germany. In 1938 he was arrested by Gestapo for criticizing Nazi policies and was imprisoned in the Dachau concentration camp. After the end of the war he stayed and lived in Germany for the rest of his life together with his family.

Post link

Estonian soldiers with British 18 pound guns during the Estonian War of Independence / Russian civil war.

Post link

Arkhangelsk. American patrol on Troitsky Avenue (October 12, 1918).

Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan

Post link

Commander of the Petrograd Military District, General L. G. Kornilov March 13, 1917 at the Winter Palace

Post link

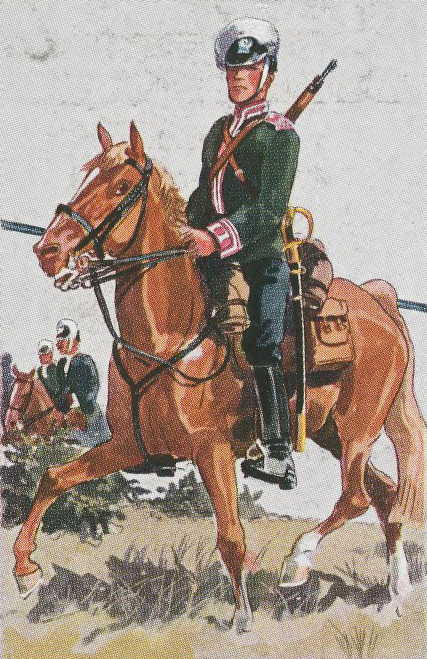

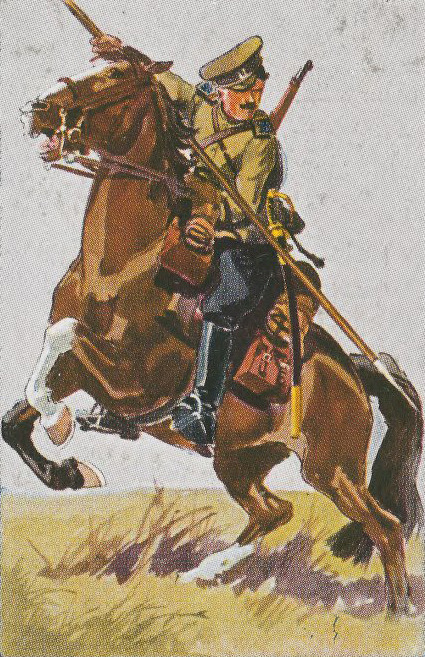

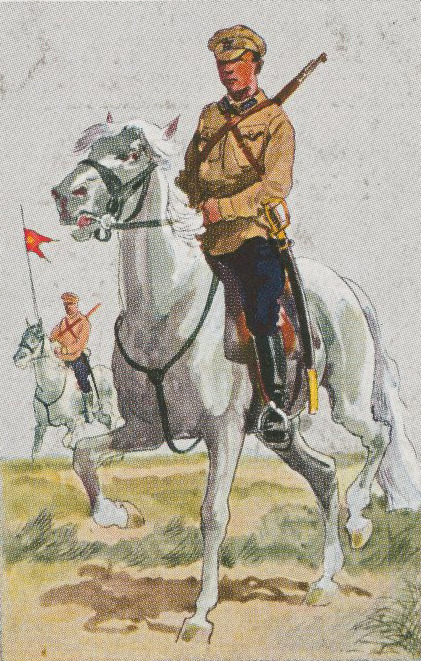

Various Russian and Soviet cavalrymen, 1914-32.

From the Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection.

Post link

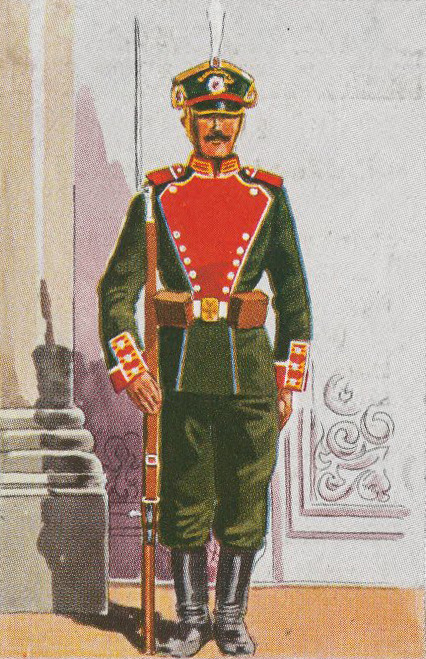

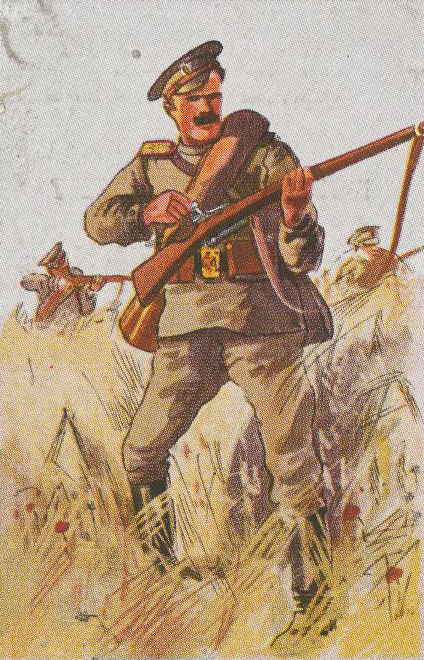

Various Russian and Soviet soldiers, 1914-32.

From the Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection.

Post link