#zee sociology

In 2007, María Sumire led new legislation to implement Article 48 from the Peruvian Constitution. Law 29735 introduces individual rights on the use, preservation, growth, recuperation, and diffusion of Indigenous languages. A public information campaign promoted the new laws (“Speak your language, it’s your right). The law facilitates regulated access to an interpreter when accessing social services, new public service hiring laws, and targeted bilingual education policies.

Cusco, Ayacucho, and other Indigenous regions funded not-for-profits to improve language services, schools were mandated to teach Quechua and other local Indigenous languages, and courts and other public services also incorporated bilingual processes.

In Cusco, Quechua is an official regional language, meaning that public servants must speak at least basic Quechua. It has one of the largest budgets and governance structures, due to high revenue from tourism, allowing the region to invest in Quechuan language autonomy.

Post link

The Economic and Social Costs of COVID-19

This is the last in this series about Race and COVID-19. Our panel looks at the impact of the pandemic on undocumented migrant workers, whose labour is exploited in Australia. The economy depends upon the work of racialised people, exposing them to high risk through the casualised frontline services that have kept the health system, and other businesses, going during lockdown. At the same time, racialised people are provided inadequate protections against infection, including poor personal protective equipment. Racialised people in general are disproportionately employed in sectors that have the highest rates of Coronavirus, including in hospitals, factories and abattoirs, where they are given little workplace rights, including sick leave. In other cases, migrant workers and international students were left without a safety net when Australia went into lockdown. They were simply told to go home, or else make do without the economic subsidies available to other Australians, even though for many of these migrants, Australia is their home.

Our panellists talk about the ‘punitive immigration policies’ which have impacted undocumented workers during the Coronavirus crisis, and how the theory on ‘curated storytelling’ plays out in race dynamics during the pandemic.

Panellists

Sanmati Verma is an Accredited Specialist in Immigration Law. She has practiced exclusively in the area of migration law since her admission to practice in 2010. She is a migrant rights activist and immigration lawyer with the United Workers Union and the Migrant Workers Centre. In addition to her practice, Sanmati conducts regular community legal education and training seminars in refugee and migration law. She is currently a member of the Law Institute of Victoria’s ‘Legacy Caseload Working Group’ and was previously the chair of the Refugee Law Reform Committee. Sanmati was nominated for the Law Council of Australia’s award for Young Migration Lawyer of the Year in 2014 and 2015.

Sujatha Fernandes is a Professor of Political Economy and Sociology at the University of Sydney. Previously she was a Professor of Sociology at Queens College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York. Fernandes is the author of Cuba Represent! Cuban Arts, State Power, and the Making of New Revolutionary Cultures (Duke University Press, 2006), Who Can Stop the Drums? Urban Social Movements in Chávez’s Venezuela (Duke University Press, 2010), Close to the Edge: In Search of the Global Hip Hop Generation (Verso, 2011), and Curated Stories: The Uses and Misuses of Storytelling (Oxford University Press, 2017). Her latest book is The Cuban Hustle: Culture, Politics, Everyday Life (Duke University Press, 2020). She is an editorial board member of Transition: The Magazine of Africa and the Diaspora.SHOW LESS

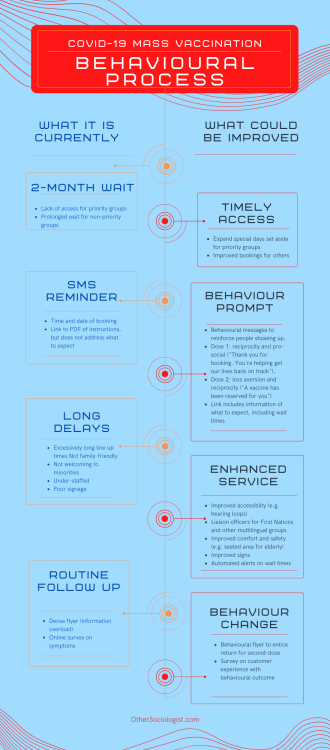

COVID-19 mass vaccination behavioural process

From participant observation research conducted in late July to mid-August.

- Wait times for bookings at the Sydney mass vaccination site are up to two months for non-priority groups

- Despite holding pre-scheduled appointments, on the day, the public lines up outdoors for up to two-hours. This makes for a physically uncomfortable and de-motivating experience

- Behavioural barriers during the mass vaccination experience may impact people’s willingness to return for their second dose in a timely way. For example:

- the line-up system is confusing

- it’s hard to hear staff directions

- inadequate accessibility

- lack of social distancing outdoors

- few signs and instructions

- lacking cultural safety for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

- poorly promoted multilingual services for migrants

- insufficient communication about extended wait times mean people may not be properly prepared to stand in line for so long

- Behavioural science evidence could be used to improve the customer service experience, by:

- improving physical cues, to encourage COVID-19 safe behaviours, and

- using behavioural messages to motivate customers to return for their second vaccination dose on time.

Read more on my blog.

[Image: Infographic on COVID-19 Mass Vaccinaton Behavioural process. On the left, what it is currently: 2 month wait, routine sms, long delays, routine follow-up. On the right what could be improved: timely access, behavioural prompt, enhanced service]

Post link

Lockdown, Healthcare and Racist Ableism

In Episode 4 of our Race in Society series, Associate Professor Alana Lentin and I spoke with three health experts to unpack how racist ableism drives the management of lockdown and healthcare during the pandemic. Ableism is the discrimination of disabled people, based on the belief that able-bodied people (people without disability) are superior, and the taken-for-granted assumptions that able-bodied experiences are “natural,” “normal” and universal. Racist ableism describes how ableism intersects with racial discrimination (unfair treatment and lack of opportunities, due to ascribed racial markers such as skin colour or other perceived physical features, ancestry, national or ethnic origin, or immigrant status).

In “Lockdown, Healthcare and Racist Ableism,” we explore the ways in which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living with disabilities can be better supported in the health system, how to establish cultural safety during the pandemic, and what an anti-racist response to healthcare might look like.

First, we spoke with June Riemer, the Deputy Chief Executive Officer of the First Peoples Disability Network. She discussed the Network’s advocacy on the Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability, and the impact of COVID-19 on Aboriginal people with disability. Second, Associate Professor Lilon Bandler is a Principal Research Fellow for Leaders in Indigenous Medical Education Network. She spoke about cultural safety and the imposition of heavier restrictions on racial minorities during lockdown. Finally, Dr. Chris Lemoh is an infectious disease expert and general physician at Monash University Health. He discussed his advice to the Victorian Department of Health and Human Services, after the Department put nine social housing towers in Melbourne under heavily armed police lockdown. The majority of these residents were migrants and refugees. No other neighbourhood was policed in Melbourne in the same way.

These patterns are now being repeated in Sydney. Eight multicultural suburbs have been put into a “hard lockdown,” including visits by police and military personnel. To see how our guests’ work still resonates in the current context, watch our video, and read a summary below.

Post link

Policing Public Health

Without warning, on 3 July 2020, the Victorian Government placed 3,000 people living in nine social housing towers into a police-enforced lockdown. They aimed to contain the spread of COVID-19 infection by targeting disadvantaged migrants who were in a dependent relationship with the state (social housing tenants live in buildings owned by the Government). Ultimately, this racial targeting did not work. The entire state of Victoria was still placed into lockdown, which lasted almost four months.

The Melbourne example shows police-enforced segregation of multicultural communities is an ineffective public health model. It is therefore profoundly concerning that such recent history is currently being repeated in Sydney almost exactly one year later.

Announced suddenly on 30 July 2021, police and the military have been deployed into eight multicultural suburbs in South West and Western Sydney, to enforce lockdown through door-to-door visits. Military personnel are not mandated to be vaccinated. This show of state force was not used in previous outbreaks involving white, middle class people in the Northern Beaches, or at the start of the present lockdown, in Bondi.

Heavily policing public health in places where Aboriginal people, migrants and other working class people live sends a damaging message to those communities. There are potential health risks with this plan, including to mental health and safety.

Let’s reflect on some of the lessons from Melbourne, and then explore how racist ableism is operating in the current “hard lockdown” of select multicultural suburbs in Sydney.

Post link

Race, Class and the Delta Outbreak

Three states in Australia are presently under a strict COVID-19 lockdown: New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia. New South Wales is experiencing a major Delta variant outbreak, which is highly contagious. It has spread to the other states through working-class workers, who do not have the luxury of working from home. Similarly to what happened in the harsh Melbourne lockdown in 2020, residents in migrant communities have been placed into a tougher lockdown relative to others, even as they are required to continue working, and submit to COVID testing every three days (“surveillance testing”).Public discourse about the COVID-19 outbreaks continues to be racially coded in media articles and in press conferences. This contributes to a moral panic about racialised people. Blame is placed on multicultural communities for not listening to public health messages, even though the majority of cases originate in ‘essential’ workplaces that are not required to shut down. As some communities remain confused about public health messages, state responses have been heavily criticised for not promoting culturally-appropriate public communication campaigns, while targeting migrants with a heavy police presence.

[Iarge: entrace to supermarket. Stickers on the ground say “Please stand here”]

Post link

Media Representations of Race and the Pandemic

In Episode 3 of Race in Society (video below), Associate Professor Alana Lentin and I lead a panel about how mainstream media create sensationalist accounts of the pandemic, and the proactive ways in which Aboriginal people and Asian people in particular lead their own responses. We spoke with Dr Summer May Finlay, a Yorta Yorta woman and Public Health Researcher at the Universities of Wollongong and Canberra. In our video below, she details how Aboriginal community controlled health organisations have effectively dealt with COVID-19 using social marketing campaigns. We also chatted with Dr Karen Schamberger, an independent curator and historian. She covers the history of Australian sinophobia (the fear of China, its people and or its culture), and how anti-Chinese racism plays out in media reports on racism and the COVID-19 pandemic. This issue remains pertinent, given that the suburbs currently under strict lockdown in Sydney have relatively large Asian populations.

Post link

Applied Sociology of Qualifications

Our research shows that more apprentices and trainees will complete their training if students are given six behaviourally informed SMS prompts. Messages provided timely and practical advice on workplace rights, and where to seek support if they were struggling. Our results equate to 16% fewer learners dropping out. Our intervention led to a 7:1 return on investment.

Post link

Ending discrimination against gender and sexual minorities requires major social transformation. Institutional change is paramount. As you keep fighting to make your organisation accountable, here are three small but impactful things you can do at your workplace to end this form of discrimination.

[Image: paste up of a woman that reads “diversity is hope”]

Post link

Interview: The Folk Devil Made Me Do It

Here’s an excerpt from my interview on NPR’s Code Switch on moral panics about critical race theory.

ZULEYKA ZEVALLOS: Moral panics are hooking into something that seems new or novel or something that’s topical, but it’s hooking into old debates, an idea that this new thing that’s happening could spell the end to our society to the way in which we live…

GENE DEMBY: ….Moral panics are a sociological phenomenon. And it turns out there are quite a few academics who study them and how they work, like Zuleyka Zevallos. She’s a sociologist and a policy researcher in Sydney, Australia. And relevant to our interests here on CODE SWITCH, Zuleyka studies moral panics and what they have to do with race. And she told me that moral panics tend to have some broad things in common.

ZEVALLOS: So there are effectively three components to a moral panic. The first is that the threat is perceived as new, but it’s been linked to old notions of other things that society has been afraid of in the past…

DEMBY: The second component of a moral panic, Zuleyka told me, is that whatever the current thing that people are freaking out about is seen as both damaging by itself, right? But also, it is seen as a harbinger of some deeper, potentially more dangerous societal problem. So go back to video games again. Video games were thought to represent a new permissiveness around violence. You know, so many games focus on fighting and shooting and Mario Karting. People will blame video games for things like school shooting and rising violent crime. There was even a congressional hearing about the specific dangerous posed by video games in the 1990s.

ZEVALLOS: And then the third component is that it needs to be an issue that lots of people can see, but the threat seems difficult. It seems opaque.

DEMBY: So it has to be something that people can point to, like something that exists in the world, again, but that if you’re on the outside of it, you can’t quite make sense of it – at least not on your own.

ZEVALLOS: It means that the general public are relying on experts to explain what’s happening to them.

Post link

Policing the Quarantine

Heavy-handed policing was deployed in response to the Covid-19 outbreak in the nine tower blocks in Melbourne where residents are mainly Black, Brown and Asian. Fines have been administered more in suburbs where the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and/or migrant population is higher. But, the same logics of colonial policing used for over 200 years are also affecting other groups at a time when a policing, rather than a public-health oriented, response to the pandemic is being rolled-out by state governments with the use of fines, lockdowns, curfews, and even prison sentences against those who are seen as failing to comply with Covid orders.

Panellists

Roxanne Moore is a Noongar woman and human rights lawyer from Margaret River in Western Australia. She is the Executive Officer for the National Peak body on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Services (NATSILS ). Previously, Roxanne was an Indigenous Rights Campaigner with Amnesty International Australia and Principal Advisor to Change the Record Coalition. Roxanne has worked for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner at the Australian Human Rights Commission, as Principal Associate to the Hon Chief Justice Wayne Martin AC QC; as a commercial litigator; and has international experience with UNHCR Jordan and New York University’s Global Justice Clinic. Roxanne studied law at the University of WA, and completed an LLM (International Legal Studies) at NYU, specialising in human rights law, as a 2013 Fulbright Western Australian Scholar. Professor

Megan Davis is Pro Vice-Chancellor Indigenous and Professor of Law at UNSW. She is Acting Commissioner of the NSW Land and Environment Court and was recently appointed the Balnaves Chair in Constitutional Law. Professor Davis currently serves as a United Nations expert with the UN Human Rights Council’s Expert Mechanism on the rights of Indigenous peoples based in UN Geneva. Megan is an Acting Commissioner of the NSW Land and Environment Court. Professor Davis is a Fellow of the Australian Academy of Law and a Fellow of the Australian Academy of Social Sciences. She is a member of the NSW Sentencing Council and an Australian Rugby League Commissioner. Professor Davis was Director of the Indigenous Law Centre, UNSW Law from 2006-2016. Professor Davis is formerly Chair and expert member of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (2011-2016). As UNPFII expert she was the focal point for UN Women and UN AIDS. During this period of UN service, Megan was the Rapporteur of the UN EGM on an Optional Protocol to the UNDRIP in 2015, the Rapporteur of the UN EGM on Combating violence against Indigenous women and girls in 2011 and the UN Rapporteur for the International EGM on Indigenous Youth in 2012. Megan has extensive experience as an international lawyer at the UN and participated in the drafting of the UNDRIP from 1999-2004 and is a former UN Fellow of the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights in Geneva.

Dr Vicki Sentas is a senior lecturer in the Faculty of Law at UNSW. She researches processes of criminalisation and racialisation in law and policing. She teaches in criminal law, criminology and policing and coordinates the Police Powers Clinic, an experiential learning course, in partnership with Redfern Legal Centre. Her recent and current research projects examine: the effects of counter-terrorism practices on criminal justice and racialised peoples; the criminalisation of armed conflicts, self-determination and diasporas through the use of security lists; police powers and their relationship to diverse forms of regulation including pre-emption and prosecution; police accountability and criminal justice reform.

Public Science and Tropes

My research on harassment of public scientists and racist Hollywood tropes is featured in two new books!

Post link

My Work Translated Into Italian

My work on “What is Applied Sociology?,” has been translated into Italian and published by Sociologia Clinica and Homeless Book publishers. The translation is published as a free eBook, Che cos’è la sociologia applicata una breve introduzione.

Check it out!

My work has been previously translated into French and a forthcoming publication will be in Persian.

Post link

Interracial Friendships

Below is an excerpt from a new interview with me, by Santilla Chingaipe, published on ABC Life.

“Research shows that white people do not have many racial minority friends,” says Sydney-based applied sociologist Zuleyka Zevallos. Dr Zevallos points to one US study that found for the average white person, over 90 per cent of their social networks are also white. “And the average white person will only have one Black friend, one Asian friend, or whatever.” […]

“One of the areas where friendships are less explicit is around race,” Dr Zevallos says. “There are lots of norms about race that people bring into their friendships, but by virtue of being a racial minority, Aboriginal people, and other people of colour who are migrant and refugee background people, will be more aware and have spent a lot more time thinking about these things.” […]

What happens when friends don’t want to engage with conversations around race? Dr Zevallos says that is indicative of how narrowly race is understood in Australia.

“It allows them [white people] to opt out whenever they feel like it. When they get tired and they don’t want to think about the benefits of the way society is organised around race,” she says.

So, what does a healthy interracial friendship look like? Dr Zevallos says it requires all parties to do the work. But for racial minorities, she argues that includes placing boundaries on friendships.

“Nobody, especially racial minorities, should be expected to be educating people one-on-one on race when there are millions of free resources online,” she says. “Just as we learn to drive or just as we learn new skills … if we’re not willing to make the time to learn about race, then I would probably say that we do not deserve to have the benefits — the warmth, the love that comes from interracial friendships — until we’re willing to do that work.”

Read more on ABC Life.

Post link

Pandemic Misinformation

I spoke with Angeline Chew Longshore from The Mauimama about my article, “Using sociology to think critically about Coronavirus COVID-19 studies.” We talked about how I was motivated to write about the sociology of science because I saw so many people struggling to make sense of the pandemic. We discussed how national cultures are impacting responses to the virus, why precarious employment in healthcare is causing high rates of infection, and how we can better check whether the information we hear is credible.

The pandemic is scary, and so much conflicting advice can be difficult to sort through. A quick way in which we can make sense of what we think we hear in news and social media is to ask four questions:

- Why do I think this is true?

- Where did I get this information?

- Whose interest does it serve?

- Does this maintain the status quo?

If something seems too neat, or convenient, or only helps a narrow group in power, it is best we dig deeper into the theories, methods and conclusions. Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.

Watch the video interview on my blog.

Post link

Race and education

I was interviewed by Metro (UK) for their series, The State of Racism:

“…Race is a social construction,” says Dr. Zuleyka Zevallos, Adjunct Research Fellow at Swinburne University. “Race is a system of classification and stratification, based on perceived biological differences. Race is stratification because these categories rank some groups as superior to others. It’s not based on some innate and immutable scientific fact.”

Read more on Metro UK.

Post link

Intersectionality and the Virus

American legal Professor, Kimberlé Crenshaw, is one of the original theorists of intersectionality. She used intersectionality as a way to show that Black women in the USA experience multiple inequalities. Writing in 1989, Professor Crenshaw showed that industrial law treated racial and sexual discrimination as distinct experiences. She showed that Black women experience both racism and sexism simultaneously, and so the impact of each is compounded. Professor Patricia Hill Collins and other theorists have shown that, without using this term specifically, people in the Global South have used intersectionality as an analytical tool since at least the 1800s, to grapple with the complexity of discrimination. In Australia, we look to the works of Professor Aileen Moreton-Robinson, such as her book Talkin’ Up to the White Woman, which examines how White feminist research has established authority through mobilising whiteness and enacting power over Aborginal women. Intersectionality is not an identity, but rather a way to understand power relations and social inequality, by looking at the interconnections of social division, such as race, gender, disability, sexuality and class. Our panel today will examine the intersections of race, gender and socioeconomics which impact the work by Aboriginal healthcare workers; how social norms of whiteness and anti-blackness are playing out during the pandemic; and how intersectionality can help shine a light on gender and sexual violence under social isolation.

Panellists

Karl Briscoe is a proud Kuku Yalanji man from Mossman – Daintree area of Far North Queensland and has worked for over 18 years in the health sector at various levels of government and non-government including local, state and national levels. He is currently the CEO of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Worker Association (NATSIHWA).

Professor Karen Farquharson is Head of the School of Social and Political Sciences and Professor of Sociology at the University of Melbourne. Her research is focused on the sociology of ‘race’ and racism, ethnicity, and diversity, particularly in the contexts of media and sport. Her recent work has looked at how organisations manage diversity including organisational opportunities for and barriers to increasing diversity. Karen is co-author of three books including Qualitative Social Research: Contemporary Methods for the Digital Age (2016) and co-editor of three collections, most recently Australian Media and the Politics of Belonging (2018) and Relating Worlds of Racism: Dehumanisation, Belonging, and the Normativity of European Whiteness (2018).

Dr Nilmini Fernando is a Sri Lankan Australian scholar of Postcolonial/Black Feminisms. Her Doctoral research theorized Postcolonial Asylum in the Irish settler colonial context through an intersectional analysis of gendered racism and state power at the asylum/migration nexus. As a practice-based scholar at WIRE Women’s Information Melbourne, Nilmini’s focus has been to critique race-evasive mainstream identity-based applications of intersectionality and develop a Critical Intersectionality Praxis model for the Australian context. She is currently a Research Fellow on the Breaking the Racial Silence’ project at Griffith University. Her publications include The Discursive Violence of Postcolonial Asylum 2017), Financial Abuse in the family violence context, (WIRE 2018) and forthcoming in the Routledge Encyclopedia of Race and Racism, and Journal of Intercultural studies

Sociologist at Work

The following is an excerpt; the second of a two-part interview with me on Mendeley Careers. (Find part one here.)

Everyone knows how hard it is to get a tenure track role, but we maintain this illusion that this is the only way we can have a fulfilling job. I advise researchers to look beyond the stigma: once you step off the academic track, there’s a world of opportunities. I’ve done work with government, I’ve led a research team investigating environmental health and safety, I’ve worked with nonprofits. I come to my career with the knowledge that there is a lot of fluidity in what I can do. I may do a lot of consulting for a while, and then go back into working for a traditional research organisation.

Researchers should know: our skills are highly valued outside academia, we need to learn how to market them. We should find a way to show to clients and employers how those research skills can be useful. If you can master that, potential employers and clients will give you amazing opportunities. For example, I once went to a job interview for a role as a researcher, and based solely on the questions I asked, the employers in question offered me a management role on the spot.

A non-academic career role is nothing to be ashamed of; it is a source of pride that strengthens research impact on society, as it brings knowledge to new sectors. There are many, many organisations which are in dire need of scientific skills and expertise; in the process, you can achieve great progress for a variety of communities.

Read more on Mendeley Careers.

Post link

Interracial Dating: Pushing Past Prejudice

I was interviewed on Triple J. The show explored listeners’ experiences of sexual fetishisation and prejudice in relationships, as well as what it’s like being partned with people from minority backgrounds.

[Image: A woman and woman hold hands, with their arms in the air]

Post link

Sociology at Work

The following is an excerpt; the first of a two-part interview with me on Mendeley Careers.

Your speciality is the “Sociology of Work” – what are your sociological observations of the research workplace?

My focus is on gender equity and diversity. I have worked with many different organisations as a consultant and project manager; I’ve instructed them on how to review, enhance, and evaluate effectiveness of different policies. I’ve also provided consultancy on how to provide training at different levels so organisations can better understand their obligations and responsibilities.

Post link

After completing my PhD at the end of 2004, I continued to work as a lecturer. I left in 2006 because there was no job security in academia. I found it difficult to find full-time academic work in my field, but once I started looking in business and policy sectors, the job choices were surprisingly abundant. I’ve reflected on the fact that, at first, it was very disheartening to give up on my dream job in academia, but once I realised the multiple career possibilities in other industries, the decision to leave was empowering.

A career beyond academia leads to diverse experiences, and the work will likely take you to places you may not have expected. Having had little luck for months trying to get an academic job, I decided to apply for unconventional roles that sounded interesting. I received a number of different offers, which showed me how valuable my PhD degree was to non-academic employers. I took a job in federal government as a Social Scientist. I moved interstate to take the position. Within five years, I had led two interdisciplinary team projects working on social modeling and intercultural communication, and I also conducted research on a range of topics, from political violence to media analysis to the socio-economic outcomes of migrants and refugees. The role was varied so that I worked with many different clients, and I also attended conferences and published articles, which kept me engaged with my academic peers.

In late 2011, I decided to move back to my home state permanently. I worked as a Senior Analyst on an environmental health and safety investigation. I led a team of 23 researchers examining 30 years worth of reports and company data, as well as analysing interviews with 300 emergency service workers. We evaluated the connections between training and environmental practices, the chemicals used during exercises, and the high rate of cancer and other illnesses amongst emergency service workers.

After the investigation ended, I decided to set up my business. I had plenty of leadership experience, and had worked autonomously in setting up various projects in my previous roles, plus I had worked with many different client groups. Setting up the business required a lot of research, and I also took a business management course. I’ve been working as a consultant for the past couple of years.

Diversity has been an ongoing theme of my research. I’ve been working on diversity issues in science and business. This includes how social science can be used to improve management of multicultural workplaces, and how gender diversity is important to the Internet. There is a lack of diversity in sociology that also needs attention. Our traditions still privilege the knowledge of White researchers from Europe and North America, but we also have a narrow academic vision of what it means to practice sociology. Similarly other sciences are structured around the skills and knowledge of White middle class men.

[Image: the entrance to Chinatown, Melbourne]

Post link

Sociology for Women

Over on my research blog, The Other Sociologist, I’ve written about How Media Hype Hurts Public Knowledge of Science. I discuss how scientists can better support public education by critiquing poor science reporting in the news. A recent example involved the media reporting that most people think that astrology is a science. This “factoid” came from a large study by the American National Science Foundation, but the results were quoted out of context and needed scientific critique. The broader study actually shows that the public do not really understand what scientists do, how our research is funded and the outputs of our work. This lack of knowledge undermines the public’s general understanding and trust in science. I argued that more scientists can get involved in diverse outreach activities to support public learning. This is part of a long-standing series I’ve been writing on how to improve public science education. Read more my blog.

On Sociology at Work, I talked about How Sociology Class Discussions Benefit Your Career. I used this post to highlight how the group work we do during an undergraduate degree trains students for the types of activities they’ll carry out as applied researchers outside academia. This includes dealing with clients, running community consultations and thinking critically on our feet. Learn more.

The rest of this post is about my most recent writing on gender equality in business and in science and technology.

Post link

Public Sociology and the Pandemic

It’s been a long while! Over the past couple of months, in my paid work, I’ve been co-leading a large randomised control trial in public health. Hoping we can publish results in the new year. Our team is also busy researching issues of technology and safety. In my personal research, Associate Professor Alana Lentin and I wrapped up series 1 of Race in Society. We covered media representations; the lockdown and ableism; intersectionality; policing; and economics. I’ll bring you write ups of other episodes soon, or head to our YouTube to watch the videos.

In case you missed it, here are two interviews I gave earlier in the year, on the sociology of COVID-19. Unfortunately, the topics of moral panics and misinformation remain relevant.

Post link

Indigenous Sovereignty and Responses to COVID-19

In Episode 2 of Race in Society, Associate Professor Alana Lentin and I are joined by Jill Gallagher, Chief Executive Officer of the Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation (VACCHO), who are leading COVID-19 pandemic responses in Victoria. She discusses how the pandemic amplifies existing health and social inequalities. Also on the panel is sociologist, Professor Aileen Moreton-Robinson, who is Professor of Indigenous Research at RMIT University, and author of countless critical race books, including, ‘The White Possessive‘. She demonstrates how her theorisation of Aboriginal sovereignty disrupts how the pandemic is currently understood. Finally, we also speak with sociologist Dr Debbie Bargallie, Senior research fellow at Griffith University, and author of the excellent new release, ‘Unmasking the Racial Contract: Indigenous voices on racism in the Australian Public Service.’ She talks about how Aboriginal people are excluded from social policy, which has compounded poor decision-making on public health during the pandemic.

[Image: people protesting holding up signs. A person holds the Aboriginal flag high]

Post link

Lockdown, Healthcare and Racist Ableism

Disability studies have long been dominated by White, non-Indigenous frameworks which ignore race. The work of Professor John Gilroy and other Aboriginal scholars show that the field of disability regularly assumes that White middle-class ways of understanding disability are universal, and they therefore enforce whiteness upon disabled bodies. Our panel today will unpack the ways in which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people living with disabilities can be better supported in the health system, how to establish cultural safety during the pandemic, and what an antiracist response to healthcare might look like.

Panellists

June Riemer is a proud Dhungutti woman from the North Coast of NSW. Throughout her career and personal life she has always championed and fought selflessly for the rights of Aboriginal people. She leads and inspires a national dedicated team and is trusted and respected by Elders across many Aboriginal communities nationally. Having worked in the community care sector for over 40 years, she shares her knowledge in an advisory capacity across multiple boards and reference groups, ensuring the rights and culture of our people are represented, respected and protected. June has represented Australia’s First People with disability alongside other Indigenous leaders, at the United Nations in both New York and Geneva. Her passion and loyalty for change is driven from the nurturing she had, from my own Elders from a young age, and it is this history that continues herjourney for change.

Lilon Bandler is Associate Professor and Principal Research Fellow for Leaders in Indigenous Medical Education (LIME) Network, working on a range of Indigenous health education projects across the spectrum of medical education. At the Sydney Medical School (2006-2019) she managed the admission pathways and provided a comprehensive support program for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander medical students, whilst she developed, implemented and evaluated the Indigenous health education program. She continues to provide GP services to rural, remote and very remote western New South Wales, Australia.

Dr Chris Lemoh practises infectious diseases medicine and refugee health. He has contributed to the development of guidelines for assessing the health of recently arrived refugees and asylum seekers. Chris has a strong interest in the relationship between social equity and health. Specific interests include refugee health, HIV in mobile and marginalised populations and cross-cultural research in sexual and reproductive health. He is a former member of the Board of the Australian Federation of AIDS Organisations and has an ongoing interest in the role of community engagement in public health research and delivery of clinical services. He also holds a Diploma in Clinical Epidemiology from Monash University and is a Fellow of the Royal Australasian College of Physicians, having trained at St Vincent’s Hospital (Melbourne) and The Alfred. He was awarded a PhD in Medicine from The University of Melbourne in 2014: his doctoral thesis concerned ‘HIV in Victoria’s African communities.’ Chris is President of the Victorian African Health Action Network.

Race in Society

Associate Professor Alana Lentin and I are both sociologists and we’ve launched a new webseries called “Race in Society.” The first season is dedicated to “Race and COVID-19.” In this first episode, we cover the inspiration for the series and why we are focusing on the pandemic.

In the video, Alana explains how our idea for Race in Society came about. We were noticing an increased interest in critical race studies among academics, students, and the broader public. Much of this discussion replicates ideas of race from North America, which is not necessarily applicable to Australia.

Post link

This is the second of two posts showing how applied sociology is used in a multi-disciplinary behavioural science project to improve social policy and program delivery.

We scaled our previous trials that used behavioural science to increase pre-service teachers’ uptake of professional placements in rural and remote New South Wales (NSW). We used timely and personalised communications, simplified research on placements, and offered a group placement experience. These interventions led to 55 pre-service teachers completing their placements at geographically isolated schools, with 100% of them saying they would consider taking up long-term employment at a rural or remote school in the future.

[Image: An Asian man is pointing to a woman’s open book as she listens intently]

Post link

This is part one of two posts showing how applied sociology is used in a multi-disciplinary behavioural science project to improve social policy and program delivery.

Our randomised control trial (RCT) sought to improve outcomes for apprentices and trainees through a behavioural intervention. Learners and their employers were separately visited to discuss contractual responsibilities and to set goals that were meaningful to the learner. Fortnightly emails to employers and text messages (SMS) to learners then reinforced these themes for a period of three months. At the end of this time, separate phone calls to employers and learners were undertaken to check their progress on goals and to work through any workplace issues. We then stopped further communication and analysed completion rates 12-months later. Though our intervention did not lead to a statistically significant result in the retention rate of learners, we suggest early, behaviourally informed support in the first 12 months can help learners persevere toward apprenticeship completion.

[Image: two people stand together. One holds a hammer, the other a paint roller]

Post link

Using sociology to think critically about Coronavirus COVID-19 studies

I’ve been thinking a lot about the role of public sociology because of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

Earlier in the pandemic, I worked with some colleagues on an early literature review scoping policy responses to the pandemic, and I’ve provided feedback on evolving policy research. As an applied sociologist, my focus has been on how race, culture, disability, gender, and other socioeconomics impact how people understand and act on public health initiatives, as well as ethical considerations of COVID research “on the run.”

Since then, I’ve been keeping up with both the research and media coverage of public health responses. I’ve been providing summaries of unfolding information on my social media (primarily Facebook and Instagram stories, as well as Twitter). This started partly to address some of the misconceptions I was seeing amongst my friends and family and I’ve kept this up as it’s been the most efficient way to help people in my life better understand what the restrictions mean for them, or to correct confusing reports.

Unfortunately, there is a lot of misinformation. People are hungry for practical advice, but don’t know who to trust (they don’t know where to look for credible resources), or they feel overwhelmed with too many conflicting directions. This is known as information overload, and it leads to poor decision-making.

One of the patterns that has been especially concerning are people writing social media posts, op eds and even setting up consultancies to profiteer from COVID-19 without any health training or policy experience. This contributes to public distrust, conspiracy theories or poor discussion that is not based on evidence. People are choosing to confirm their pre-existing beliefs, rather than engaging critically with scientific information that challenges their perspective. This is known as confirmation bias. It stops people from considering new information and different points of view that might be helpful to their wellbeing.

Reading original scientific journal articles is not always possible as there is often a paywall. Plus, science papers are, by definition, published for the academic community. The language is technical, and the principles can be hard to follow for people who are not subject matter experts. This makes it more important for scientists who have access to write about science research in an accessible manner and to share findings through different communities.

While data on COVID-19 are evolving, and no one can claim to be a definitive COVID-19 expert, the best sources to trust are official sources, such as state Health Departments, epidemiologists, virologists, health practitioners who are providing front-line services (such as Aboriginal-controlled health organisations), and policy analysts who work on COVID-19 responses. Additionally, reliable news sites include the ABC News Australia live blog, Croakey and individual health researchers, such as epidemiologist Dr Zoe Hyde (University of Western Australia) on Twitter.

If you read about a study, how do you know if you can trust the conclusions? What’s the best approach if you wanted to write about a study’s findings for a broader audience, whether it’s your friends and family reading your Facebook feed, or an article in a major news site? Today’s post gives tips for how to read a study using critical thinking principles from sociology, and things to consider if you want to write about, or share, studies that you read about.

[Image: a woman is seen from the back, she is reading]

Post link

Career Planning in the Research Sector

I’m sharing the resource I created for the Association of Iberian and Latin American Studies of Australasia Conference. This presentation is intended for early career researchers who may be near completion of a postgraduate degree, or recently completed a Masters or PhD. I look at how Latin American studies scholars can market their skills, especially given the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The lessons are applicable for other early career researchers.

You can flick through my slides, and see other resources on how to look for work, prepare a CV, and interview.

[Image: people walk through a busy festival]

Post link

Pandemic, race and moral panic

In the afternoon of 4 July 2020, Victorian Premier, Daniel Andrews, gave a press conference announcing that two more postcodes are being added to COVID-19 lockdown (making 12 in total) (McMillan & Mannix, 2020). The new postcodes under Stage-3 lockdown are 3031 Flemington and 3051 North Melbourne.

Additionally, the Victorian Government is effectively criminalising the poor: nine public housing towers are being put into complete lockdown. The Premier said: “There’s no reason to leave for five days, effective immediately.” This affects 1,345 public housing units, and approximately 3,000 residents.

Public housing lockdown is made under Public Order laws. Residents will be under police-enforced lockdown for a minimum of five days, and up to 14 days, to enable “everyone to be tested.”

How do we know this public housing order is about criminalising the poor, and driven by race? The discourse that the Premier used to legitimise this decision echoes historical moral panics and paternalistic policies that are harmful.

Let’s take a look at the moral panics over the pandemic in Australia, and how race and class are affecting the policing of “voluntary” testing.

I support continued social distancing, self-isolation for myself and others who can afford to work from home, quarantine for people who are infected so they can get the care they need without infecting others, and widespread testing for affected regions. These outcomes are best achieved through targeted public communication campaigns that address the misconceptions of the pandemic, the benefits of testing for different groups, making clear the support available for people who test positive, and addressing the structural barriers that limit people’s ability to comply with public health measures.

[Image: a woman wears a face mask]

Post link

Media Representations of Race and the Pandemic

Season 1 “Race and COVID-19,” Episode 3, ‘Media Representations of Race and the Pandemic’.

One of the outcomes of colonisation and accompanying racial rule is the control of public narratives by non-Indigenous settlers. This results in a lack of attention to the ways in which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people interpret the world. Aboriginal people have been telling stories for over 65,000 years, and we honour this expertise and wisdom. We believe it is very important to consider the role played by the media in framing public discussions of the link between race and Covid-19. Mainstream media create sensationalist accounts that spread moral panics about racialised people.

Amoral panic is when a group or event is seen as a threat to social values, usually during a time of massive social change, such as the pandemic. A moral panic whips up fear of particular groups, especially racial minorities. At the same time, it protects the interests of groups at the top of the racial hierarchy, which, in Australia, is white people of European descent.

Panellists:

Summer May Finlay is a Yorta Yorta Woman who grew up in Lake Macquarie near Newcastle. She is a Lecturer at the University of Wollongong, a Research Assistant at the University of Canberra, and a contributing editor at Croakey Health Media. She specializes in health policy, qualitative research and communications. She has worked in Aboriginal affairs at the National level and has strong professional connections across the country in the Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service sector. Her article on “Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations are taking a leading role in COVID‐19 health communication” is available here: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/f…

Dr Karen Schamberger is an independent curator and historian with interests in migration, cross-cultural relations and material culture. She is currently working with the Lambing Flat Folk Museum volunteers to redevelop an exhibition about the development of the town of Young from the goldrush, including the anti-Chinese riots in 1860-1. She has previously worked at the National Museum of Australia and Museums Victoria. Read about her research into the racism of Lambing Flat: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddes…

Running a research project as an applied sociologist

Let’s chat about what it’s like to run a typical personal research project as an applied social scientist. Outside of my paid work, I laboured on a resource on equity and diversity. I wanted to reflect on the journey.

Part of the reason why I’m sharing this is so that you can get to know me a little better, but also because many people don’t realise what it’s like to be an applied sociologist. It means all my scholarship needs to happen outside of my paid work. It is exhausting but incredibly important to my sociological practice.

Post link

Check out my resource, Intersectionality, Equity, Diversity, Inclusion, and Access. There are five individual chapters which are intentended to work together. The information is a comprehensive, though not exhaustive, introduction into the barriers and solutions to discrimination in academia and research organisations. The issues are restricted to career trajectory from postgraduate years to senior faculty for educators and researchers.

Each section includes a discussion of the theoretical and empirical literature, with practical, evidence-based solutions listed in text boxes, capturing my long-standing career in equity and diversity program management, education and research.

This resource is split into five pages, for the purposes of improving reading experience; however, all five sections are intended to paint an holistic picture for social change.

Explore the themes via this detailed table of contents.

[Image: people sit together on the ground in a large building]

Post link

I don’t post on my Other Sociologist Facebook page as often as I used to because Facebook is a racqueteering platform. Research has shown that since 2014, pages have lost at least 60% of ‘organic reach’ (that is, individual followers seeing page posts without promotions paid by brand pages). Some market research has determined that for most pages, only 6% of followers see their content, while other analysis shows it’s closer to 2%. My discussion is not new; social media analysts have been attuned to these patterns for the past decade. While the issues I discuss apply to many different companies and brand pages, I’m focusing on the impact that the Facebook model has on not-for-profit pages, specifically those like mine, which aim to educate the public for free.

Post link

When Coke launched its obesity campaign in Australia, social scientists spoke out about the problems with the messaging and strategy. The company says they are helping to combat weight-related illness by releasing smaller cans and by selling its low calorie Coke varieties. Coke also says it is providing nutritional information on its vending machines and it has teamed up with a bicycle group to encourage exercise.

This post discusses the problems with Coke’s social media marketing strategy to appear more socially conscious about public health. The issue is not about whether or not you or I drink cola occassionally; the issue is broader, about how companies blur the lines on health and junk food.

To date, Coke has tried, and failed, to improve their corporate responsibility. Coke invests a great deal of money in science as a means to address health concerns, however none of this marketing speaks to the social and health problems associated with sugary soft drinks. Addressing social science concerns would better serve Coke’s corporate change, if Coke is indeed committed to its campaign of healthy living.

Post link