#cbc diversity

By L.L. McKinney

I’m seven and falling in love with Spider-Man. I learn everything I can about this kid who has incredible powers, but (unlike all the other heroes) his city hates him. He tries his best, and people are always knocking him down for it. Sometimes he wants to give up, but he doesn’t. Somehow, he keeps going. With addiction eating at my parents and slowly tearing my family apart, Peter helps me figure out how to keep going, too.

I’m ten, and it’s the first Show-and-Tell of the year. I bring the comic my Granny gave me, the first I’ve ever owned. A group of kids near the cubbies are giving each other sneak peeks of favorite toys, books, and other things before class. Thrumming with excitement, I join them and thrust my copy of Amazing Fantasy #15 out.

A boy snorts and mutters “What do you know about Spider-Man?” Before I can answer, his friends start in on how I’m just faking. How I should’ve brought my Barbie, the “ugly” one (they know I have it). Or maybe I should’ve brought my pet watermelon. I don’t present that day, or ever again.

I’m fifteen, waiting for the 4:30 bus with some other kids, since I had to stay after class and practice with the rest of the Symphonic Orchestra. Sitting on the front steps of my high school, I sing along to “Crawling” by Linkin Park.

Someone rips my headphones off. A boy from the class ahead of mine presses them to his ears. He sucks his teeth. “Man, you listening to that white boy music.” A girl behind him giggles. “That’s cause she white.” Their little group cracks up, and he drops my headphones on the ground. Shouts of Oreo, wannabe white girl, and worse follow me home. For the rest of the year, I only listen to Hip-Hop in public.

I’m twenty, and after spending most of my life playing video games, I decide I want to make them for a living. I spend weeks researching schools and programs before finally settling on one. I save up my pennies, I pack my bags, and I move across the country to live with one of my best friends while I go to school. She tours the campus with me and helps me buy my supplies.

The first day of class, I notice I’m one of three girls. I’m the only non-white person period. I sit in the back and try not to draw attention to myself. The teacher asks us to introduce ourselves and, for an icebreaker, say what we want to change about gaming. I say I’d like to see more Black characters. After that, it only takes two days for someone to ask why I’m not in the music program, because “that’s where all the other Black people are.”

It’s another two days before someone else says they didn’t know Black people even liked video games that weren’t NBA All-Star or Madden NFL. Before the week is out, someone says I’m making a big deal out of nothing, it doesn’t matter what race the characters are. Besides “doesn’t Donkey Kong count?” When the racism escalates to anonymous threats of violence that the school does nothing about, I drop from the program.

I’m twenty-two, and Spider-Man 3 is about to hit theaters. I’ve seen the first movies multiple times on my own. I have all of the DVDs, including the special editions. One of my friends catches me looking up locations for midnight showings. “I didn’t know you like Spider-Man,” she says with a note of amusement in her voice. Without meeting her gaze, I quietly admit he’s my favorite hero, as if I’m confessing to a crime. She grunts to herself and goes about her business.

That week she surprises me with tickets for us and another friend. We meet at my parents’ place, put on Spider-Man t-shirts, and paint his mask on our faces. The theater cheers when we walk in.

I’m twenty-seven and on my way home from a Disturbed concert. I pull into a gas station, music blaring as I head-bang along. When the song ends, I climb out to go get gas. On the other side of the pump, an older Black man is staring.

It’s about to get awkward when he nods, scrunches his face, and holds up a hand, pointer and pinky fingers out. “Hell, yeah.” I return the gesture. He gets in his car and drives off, the wails of Metallica trailing behind his low rider Caddy. On the way home I roll the windows down, letting the wind hit my face, music pouring out of my car.

I’m thirty-four, and the developers for a video game I’ve been playing for a couple years, Paladins, drop a clip of their newest character: Imani.

She’s strong. She’s fierce. She’s a tamer of dragons, a wielder of magic, and she’s Black. I stare at my screen, fixated as I play the clip over and over again. I pause the video at different spots and take in every detail of her design; her wide nose, her full lips, her thick braids. I stare. I marvel. I bask. And I cry. I’m overwhelmed. There she is.

There I am.

L.L. McKinney is writer, poet, and active member of the kidlit community. She’s the creator and host of the bi-annual Pitch Slam contest and spent time in the slush by serving as a reader for agents and participating as a judge in various online writing contests. A Blade So Black is her debut novel.

Learn more about A Blade So BlackandA Dream So Dark, the first two books in L.L. McKinney’s Nightmare-Verse, a thrilling YA urban fantasy series that #1 New York Times bestselling author Angie Thomas calls “the fantasy series I’ve been waiting for my whole life.”

Many children today inherit biased language and concepts from generations before. In An ABC of Equality (Frances Lincoln, The Quarto Group, 9781786037428) debut author and intersectionality expert, Chana Ginelle Ewing offers the first children’s concept book focused on educating youth about the importance of the intersections of equality. Together with Chilean illustrator Paulina Morgan, Ewing makes complicated identity concepts like gender, immigration, and ability - accessible for children and encourages informative and constructive conversations around our modern and evolving vocabulary. Together, Ewing and Morgan offer parents a jumping off point for conversation about equality in today’s divisive world. In the Q & A below, author Chana Ginelle Ewing interviews the illustrator of An ABC of Equality, Paulina Morgan.

What excited you about taking on the project of illustrating An ABC of Equality?

I loved the concept of An ABC of Equality! I found it wonderful to be part of a project that spoke to children in such an honest way and that was able to teach such complex concepts in a simple and love-filled way. I had never seen such a book and it seemed at the same time a great challenge to accompany these words with images that also talked about equality.

Walk me through your process. How did you arrive at the imagery we see? What tools did you use?

It was a significant job to illustrate these concepts and I learned a lot in the process. The first thing I did was read, understand and feel, in order to translate into images a world in which we were all equal without leaving anyone out. Such a world must be colorful, friendly and fun. Secondly, I explored my color palette and the characters that accompany this book. I spent many hours drawing and looking for the images that best represent each concept and taking great care in each drawing to maintain the simplicity of the words. Finally, when I found the perfect characters, I added the color and gave life to the images. The tools I use are very simple, paper pencil, my digitizing tablet and tons of love.

Did you do any research on any of the words before getting started?

What seemed wonderful to me is that each concept was so well explained and so simple that I did not need to investigate much more. I did, however, investigate how these concepts had been visually interpreted and it was very enriching.

How do you feel about equality? Does the book definition resonate?

I believe that the concept of equality is one of the most necessary in this world. We must learn to accept ourselves and others. In this book, you learn that we should not fear difference and that equality makes us stronger. This book is for children and more than that, it is beneficial for everyone!

Is there any word that you didn’t know initially?

I knew almost every word, but I had never read such an open-minded and full-of-love approach. In this book, you can understand concepts that are sometimes complex such as gender, gender equality, sexuality, among others.

I am so glad we got to work together on An ABC of Equality - your illustrations beautifully articulated the expansiveness that is so needed in conversations on identity. If we worked on a part two, a 2nd book, what would you want to cover?

It would be incredible to make a second book, there are so many incredible topics that I’d love to illustrate! I love the idea of working on issues that make us better people like empowering women, friendship, self-esteem, feelings. It is great to contribute with a grain of sand to help our world.

Women and identity advocate and entrepreneur, Chana Ginelle Ewing is the Founder and CEO of Geenie, a leading women’s empowerment platform centering the stories of Black women for personal growth. She is the author of the forthcoming children’s book An ABC of Equality, illustrated by Paulina Morgan (Frances Lincoln Children’s Books, Sept 2019).

Paulina Morgan works as an independent illustrator based in Santiago de Chile. She studied design before moving to Barcelona, Spain to obtain her master’s degree in Art Direction. She worked in advertising before deciding to pursue her passion for illustration.

Stargazing by Jen Wang (First Second, September 2019). All rights reserved. @macmillanchildrensbooks

At the Mountain’s Base features powerful artwork by comics/graphics artist Weshoyot Alvitre (Tongva) in her picture book debut. Written by Traci Sorell (Cherokee), the story centers on a family waiting for their relative to return from war. Penguin’s new imprint Kokila Books connected these creators and here they share how this process worked for them.

Sorell: I had some initial trepidation about how this concise poem would be illustrated. After publisher Namrata Tripathi acquired the manuscript, she emailed me and asked if I knew your work. I didn’t and wondered how working in the comics world would translate to crafting a picture book.

What did you first think when she contacted you?

Alvitre: I was excited and surprised at the short length. Its circular pattern of imagery was just so powerful. I was both intimidated by the minimalism and eager to see what I could do with it. I also wanted to know more about you to see if I could pull from your tribe’s traditions for the art.

Sorell: You definitely pulled from Cherokee traditions. I purposefully left room for any illustrator to choose whatever tribe they wanted for the family.

What was it about weaving that spoke to your creative process?

Alvitre: I loved the concept of weaving you included as I do a lot of fiber arts and crafts. I’ve taught myself spinning on hand spindles and spinning wheels. My tribe is known for their fine basketry, but we don’t really have weavings with wool or yarns. So I learned specifics of Cherokee finger weaving and it ended up being a visual theme throughout the entire book.

Sorell: What a gorgeous theme it is! I love the yarn defining each panel. Those few double page spreads have so much impact. I delight in lifting the dust jacket and showing everyone the case cover. Your artwork throughout the entire book takes the poem to another level. Tears flow. I didn’t anticipate it would produce that type of reaction, but I’ve seen it repeatedly when I’ve shared the advance copies. Powerful!

Did you feel that emotion as you worked?

Alvitre: I always take the work I do very personal and try to get inside the characters’ heads. While making this book, I found out more about the service of my late grandfather, a decorated Marine and war veteran. Also, I was in the process of losing my grandma—an active knitter who mailed knitting patterns and instructions to a younger me. I still cherish that.

I also thought about ceremony and how prayers and songs are included, to protect people but also to mourn for them. I watched a vignette on Cherokee women reclaiming their traditional ways through language, crafts, and sewing. They were singing gospel songs and discussing the loss of language in the community but hearing its preservation at these gatherings. Reclaiming our languages, traditions, crafts and actively using them can be very emotional.

Sorell: Truth. Something else I want to know—how would you describe your debut experience?

Alvitre: Better than I could have possibly imagined! Working with such strong women, your writing, Namrata’s vision for Kokila and Jasmin’s gentle eye, I felt part of a family. I learned so much about the process of putting a children’s book together. I smile about being intimidated to enter this market, but I am eager to illustrate more. There’s so much freedom, and it’s fulfilling to read it to my children.

Sorell: Wado for sharing. I can’t wait for us to share this book with the world!

Weshoyot Alvitre is a comic book artist and illustrator. She’s most recently worked as art director for the video game When Rivers Were Trails and illustrator on the graphic novel Redrawing History with the Library Company of Philadelphia. Her books have received numerous awards and recognition, including the Eisner Award for Little Nemo: Dream Another Dream and Prism Award for Hummingbird Boys in Moonshot Volume 2. She currently resides in Southern California with her husband and two children.

By Mina Javaherbin

I grew up in prerevolutionary Iran and immigrated to the United States when I was a teen. My new book, My Grandma and Me, is an homage to a peaceful childhood, when everyday activities are bliss. When I came to America, I was running from war and revolution. It took me a long time and a considerable amount of money to follow the immigration procedures and become an American citizen. All this happened before mass immigrations, revolutions, and wars in other countries had made a noticeable dent in the American psyche. These days the internet has caused a silent revolution in everyone’s consciousness and we are more aware of our global village.

Terms such as global village,multicultural, and diversity did not trend during my childhood. However, we’ve always known about one another, and we even try to communicate—hence the United Nations. But it’s clear from the recurring disagreements and wars that sitting across a table in a large building is not enough, and a multicultural mind-set is needed to prevent things from getting lost in translation.

Immigrants have the basic foundation of becoming multicultural readily available, as we already have to deal with two cultures. But the degree of immersion varies. I can only speak of my own immigrant experience, and I’m genuinely interested in both my Iranian and American cultures. Something exquisite happens when a person opens themselves to learning about more than one belief, one lifestyle, and one language. For me, it enhanced my relationship with cultures beyond the Iranian and American.

I’m passionate about writing from my multicultural perspective, which was bolstered by my immigration but fostered from early childhood through extensive travel and multilingual education. But why should my books about different people and places be worth sharing with the lucky majority who grow up in the culture they are born into? Because technology and ease of travel has now placed us in one another’s backyards, and whether we like it or not, we have become neighbors. If we refuse to know our neighbors and instead build territorial walls, we are alienating people who most likely share similar challenges and dreams, people we could bond with and befriend. Books about people we don’t know—or are afraid of—cultivate a multicultural mind-set so that when we meet these people, we’re more comfortable with their culture.

As a multicultural author, I write to help create multicultural readers. I hope my readers wonder, What would I do or think if I lived in the world of this book? Understanding how views are formed in different settings gives us a multicultural outlook that brings about respect, sometimes to the degree of advocacy for people we disagree with. And the ability to see a multitude of viewpoints prevents a multicultural person or society from permitting the absolute rule of a singular dogma. So let’s all become multicultural and relegate wars to museums. We all deserve peaceful childhoods—and adulthoods—with our beloved grandmas.

Mina Javaherbin has written several award-winning picture books, including Soccer Star, illustrated by Renato Alarcão, and Goal!, illustrated by A. G. Ford. She lives in Southern California.

BothIsle of Blood and Stone and its standalone companion, Song of the Abyss, are about mapmakers and explorers. Why did you decide to write about these topics?

It really came down to writing what interests me. I’ve always loved adventure stories and historical fiction. The Count of Monte Cristo,Jane Eyre, and Anne of Green Gables were favorites growing up. Additionally, I’ve always loved old maps, the beautiful ones with the sea serpents and sailing ships painted onto them. And growing up, I was obsessed with the Indiana Jones movies. With this duology, I wanted to create characters inspired by Dr. Jones, young men and women who were smart and funny and who used their intellect to solve the mysteries that were at the heart of these stories.

Did any particular place inspire the maps in your book?

Most definitely. The map at the front of Isle of Blood and Stone depicts the fictional island kingdom of St. John del Mar. But if you were to google the island “Guam,” where I was raised, you would see that they are a near perfect match. Why not? I needed an island and I thought it would be fun to use the one I know best.

How do you choose your character names?

ForIsle of Blood and Stone, I was looking for old-fashioned names that were Spanish in origin. I started with ‘Mercedes,’ which I first came across in Alexandre Dumas’ The Count of Monte Cristo. Then I followed up with Elias, Jaime, and Ulises. Some names had a more personal connection. Reyna is the hero in Song of the Abyss. Reyna also happens to be my favorite cousin’s name. The village of Esperanca is named after my grandmother. And the Sea of Magdalen…well, Maggie was my mother’s name.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you be doing?

I have a library degree so I would most likely head over to the nearest public library if they’d have me. But part of the reason I became a writer is because there are so many things that fascinate me and, as a writer, I get to explore them all within the pages of a book. I would like to try my hand at being a spy, a time traveler, an arborist, an architect, a medieval military engineer, a 20th century physician. So many things!

What does being a diverse author mean to you?

I am part African American, part Pacific Islander, born on the Northern Mariana island of Saipan and raised on the neighboring U.S. Territory of Guam. I didn’t know a single Guamanian children’s author as a child. No island version of Laurie Halse Anderson or Jennifer Donnelly where I could say, “When I grow, I want to be just like her.” I hope that my story helps change that. That an island kid, thousands of miles from the New York publishing houses, will see that writing stories for a living is a possibility for them, if that is their dream.

Can you recommend any recent diverse lit titles?

I really enjoyed Sleepless by Sarah Vaughn. You rarely see people of color as the main characters in medieval fantasy lit, and this graphic novel, about a king’s daughter protected by a member of the elite Sleepless Order, is just so well done and lovely to look at.

Makiia Lucier grew up on the Pacific Island of Guam and holds degrees in journalism and library studies from the University of Oregon and the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee. She is the author of A Death-Struck Year, Isle of Blood and Stone, and Song of the Abyss.

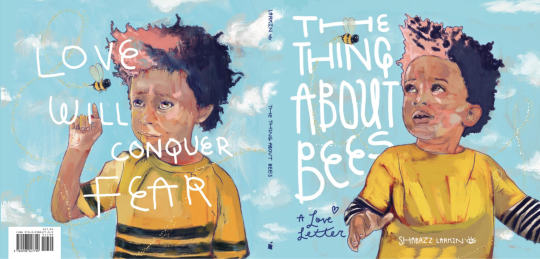

What inspired you to write The Thing About Bees?

I wrote the book because I have a ridiculous fear of bees. When my sons were born I didn’t want to pass that fear to them, so I set out to discover all I could about the little buzzers.

What did you find out?

I learned three things about bees. First I learned that every living creature has a special part to play in the world, and that includes grownups and kids. Second, when I learn more about a scary thing, the thing feels less scary to me. Third, I researched which bees and wasps are kind and which are kinda mean, and made it into a chart for the book.

What do you hope to be the takeaway to your book?

I hope kids will understand that it’s brave to understand the things that scare us. This can be scary objects like bees, but it can also be people who are different from us. The book is all about love. Love is magic. Love is super power. Love conquers fear. It’s so important that I even wrote it in big letters on the back cover of the book!

What do you think about fatherhood?

It scares me! (ha, ha!) There’s so much responsibility. I have to show my two sons how to be brave when I’m not always brave myself.

What does it mean to you to be a Black father?

I’m fortunate to have a father my whole life who loves me a great deal. He was in the military and for years would be gone six months at a time, so I had a limited role model and relied on the media to see what it was like to be a Black father. This is why it is so important to see our true experience reflected in books, tv, and movies.

You credited in the Copyright page that the art was inspired by Kehinde Wiley and Norman Rockwell. In what ways?

Kehinde Wiley is most famous for painting the official portrait of President Obama. He’s known to use Old Masters paintings as reference and then replace the figures with contemporary Black people. The first time I saw his work I was so moved I cried! I was in college and I saw this figure of a king who looked like my high school best friend. I never thought a Black man can be a king! By simply showing people in different roles it changed how I saw myself and my community. It’s so powerful!

Norman Rockwell was an inspiration for the way he showed how small town America can be so beautiful. So I followed his approach—by taking a series of posed photos of myself and my family—and showed my hometown of Nashville. But like Kehinde, I want to show a small town America with a loving Black family, and with dad spending time with his sons. There are many families like ours.

This is your third book, after your illustration debut in Farmer Will Allen and the Growing Table and your author/illustrator debut in A Moose Boosh: A Few Choice Words About Food. How are they different?

I came from an advertising background and was still finding my style when I illustrated Farmer Will Allen. The style is more traditional in what I thought children’s book illustration would look. For A Moose Boosh, I wanted to break away from tradition, so I created “vandalized art” by adding white doddleling over photos I took. It was a closer reflection of who I am. For The Thing About Bees, I started with a traditional painterly style and then add on cartoon images to give it a twist. The opening pollination chart is meant to be like a Pixar short before the movie. Something to set the mood!

Why do you think communities of color are often left out of discussions on environmental issues?

People often think city kids have very little to do with preserving our environment. But when bad things happen to our environment it always hurts the poor people first! People of color need to be aware and take action even if they often are not given a voice in these issues. We need to take action. Learn about issues. Save the bees!

Finally, what do you want readers to know about your work?

I think it’s important to remember this: You can’t be what you can’t see. I want to make books that represent the images of people that I always wanted to be, but could never find representations of people that looked like me.

Learn more about The Thing About Bees: A Love Letter through the fantastic book trailer here.

Shabazz Larkin made his picture book illustrator debut with Farmer Will Allen and the Growing Table and his author/illustrator with A Moose Boosh: A Few Choice Words About Food. Both were named Notable Children’s books by the American Library Association and published by READERS to EATERS. He is a multi-disciplinary artist and an advertising creative director. He lives in Nashville, Tennessee, with his wife and two sons. More about Shabazz at shabazzlarkin.com. Follow him @shabazzlarkin.

There are two Black queer girls from two different Black cultures in this book falling in love. What was it like writing a Caribbean and Black American protagonist?

As a first generation Caribbean-American author, I got to connect with the spectrum and multitudes of Blackness that shaped me through writing this book. Audre and Mabel represent aspects of who I am as a Black women who was raised in multiple Black cultures. My mother is Trinidadian and my father is from St. Croix, and I was born and raised in Minneapolis, Minnesota. I loved writing these girls, because they represented parts of me and the Black diaspora in a way that was eclectic, vibrant and healing.

In writing Audre and Mabel, I wanted to show them falling in love with a Black girl, that was a reflection of them, but also unique and magical in a way all her own. Their love is one that I longed to read as a young person. One that centered weird Black girls in a romantic love.

You traveled to Trinidad and Tobago to interview folks who are LGBTQIA on these islands. How did that research affect the story?

I wanted to depict with love, curiosity and expansiveness the experience of being queer in Trinidad and Tobago (T&T). There are a lot of assumptions in the mainstream about the backwardness of attitudes towards LGBTQIA folks in the Caribbean region, and this isn’t the only truth. There is also the notion that folks in the U.S. are inherently more progressive and this is not the case. I learned from activists in T&T, that colonialism and religious evangelism from the west has fostered a lot of the homophobic sentiments that persist in the region.

I traveled to T&T to interview artists, students, activists, government employees, queer party organizers, etc to get their perspective on queer life in T&T. It was a true gift to hear Trinibagoans talk about their queerness and speak to the ways that they live out loud despite bigotry and ignorance about who they are. There were stories of people being exiled from family, as well as others who were embraced and accepted for their queerness. On a personal note, I traveled there with my wife, and was grateful for how we were embraced by my Trinidadian relatives in ways that was affirming and healing.

Ancestral spirituality, astrology and natural healing are all themes in this book. Why were these themes important for you to include in this book?

With Audre and Mabel, I wanted them to explore relationships with the divine and the sacred that helped them navigate the world and challenges they were up against. As a young person, I loved anything that was mystical and otherworldly, things that seemed connected to intuition and spirit. I wanted these Black girls to be spiritual seekers in a way that empowered and blossomed them. They have to deal with some heavy and difficult realities that required spiritual skill sets that were ancestral, organic and cosmic. I have always loved astrology and love the ways that it has helped me see other realities within myself. The character of Queenie, Audre’s grandmother, represents how Black people can be spiritual in a way that is shaped out of intuition and deep listening.

Who are the authors who inspired you in writing this book?

As an 11 year-old, I found a book called The Friends, written by Rosa Guy and it was the first book that centered a Black Caribbean girl as the protagonist, and I felt I could relate to. I had always been an avid reader but reading Black women authors in my teen years is what made me want to write and process who I was on the page. I read a lot of Maya Angelou, Octavia Butler and Jamaica Kincaid. I am deeply influenced by poeticism and lyricism from writers like Ntozake Shange and Nikki Giovanni. I fell in love with Alice Walker and the way she wrote Black women’s interiors in a way that was beautiful, sensual, and complex. Toni Morrison, who has just passed and is a literary goddess AND genius, taught me how to be unapologetically experimental and otherworldly. She showed how you could write Black life, while making it accessible in its mundane and honesty of who we are. I have discovered, Alexis DeVeaux and Sharon Bridgforth, in my later years who are mentors of mine and have helped me feel affirmed in writing Black queer stories.

The relationship between Whitney Houston and her best friend Robyn Crawford is a major theme in this book. What inspired that theme?

In this book Whitney Houston represents invisible queerness within Black memory as well as the greater culture. A couple months into writing the book, her legacy unlocked a dimension of the book that was needed for me to understand the erasure of queerness within Black life and memory.

When I was growing up in the 1980s I idolized Whitney Houston. She was beautiful, elegant and had a voice and presence that was bewitching. She was one of the Black celebrity icons that took the grit and gospel of Black life, and made it into an expansive and tender world for the mainstream. I didn’t learn until 2006 when I was in my twenties living in New York City about Whitney and her long-time best friend, Robyn and how central a figure she was to Houston’s life and career. Learning about this bond that was deep and most likely romantic, made Whitney make more sense to me. I loved re-imagining them in ways for this book that wasn’t tinged with stigma and controversy, but instead love and sweetness.

Junauda Petrus is a writer, pleasure activist, filmmaker and performance artist, born on Dakota land of Black-Caribbean descent. Her work centers around wildness, queerness, Black-diasporic-futurism, ancestral healing, sweetness, shimmer and liberation. She lives in Minneapolis with her wife and family. You can visit her at www.junauda.com.

By Natasha Díaz

As a white-presenting, multiracial Jewish woman, I looked like most of the protagonists in the books that I read growing up (aka white girls), but I never related to them. I didn’t understand why all the characters somehow came from families that seemed exactly the same. These casually all-white, anglo universes weren’t a part of my reality, and as much as I appeared as though I should, I did not I see myself mirrored in the pages.

When I got a little older, I realized that if I searched, there were books that featured mixed-race and Jewish characters. If it was a Jewish narrative, the book was almost always about the Holocaust. In the stories I found with characters of mixed race, more often than not, biracial and multiracial narratives focused on their external appearance and exoticized the character’s “European features” praising “light eyes” or “silky hair” or “thin noses,” reinforcing the sentiment that the lack of visual connection to their Black or Brown heritage made them special or more beautiful and desirable. The stories rarely delved into the internal struggle so many people of mixed heritage experience with feelings of unworthiness to themselves and their histories. Biracial and multiracial characters were written as victims of their “light-skinned plight,” often bullied by darker-skinned people in their families and communities. (I should pause here to state for the record that not all mixed or biracial or multiracial people have a white parent, and not all people with mixed racial and ethnic heritage, even those who do have a white parent, look white or are light-skinned. There are many mixed people who present as Black and Brown and are subject to the same prejudices that monoracial people of color experience.) But it seemed as though all mixed people were being portrayed in one way. And as readers, we were asked to pity and empathize with the hardship of not fitting in as a result of a lighter skin tone without ever acknowledging the negative impact that perpetuating these colorist ideas has on communities of color.

When I decided to finally write the book that would eventually become Color Me In, I promised myself that I would create a world on the page that my younger self needed. One that looked and sounded the way mine did when I woke up every day, filled with a blend of races and communities that didn’t shy away from the uniquely complicated experience of being multiracial and white-passing, as well as Jewish in ethnicity without much connection to Judaism as a religion. I wanted to write a character who learns not only to take pride in her various cultures but also to take responsibility and accountability for her privileges as she tries desperately to make herself feel whole. I wanted to write something messy, the way the world is, especially when you move through it as a gray area personified.

I wrote Color Me In because I want young people to know they have a right to take ownership of their identities, and that when they do so, it is important to recognize where they fit within the cycles of systemic injustice that plague our country. I wrote Color Me In because I want young people to find strength in their unique backgrounds and experiences and to use that power to rise up and be loud in the fight for equality because we need them now more than ever.

Natasha Díaz is a freelance writer and producer. As a screenwriter, Natasha has been a quarterfinalist in the Austin Film Festival and a finalist for both the NALIP Diverse Women in Media Fellowship and the Sundance Episodic Story Lab. Her personal essays have been published in the Establishment and the Huffington Post.Color Me In is her debut young adult novel. Originally from New York City, Natasha now lives in Oakland, California.

natashaerikadiaz.com @TashiDiaz on Twitter @NatashaErikaDiaz on Instagram and Facebook.

What inspired you to write Count Me In?

In 2013 Dr. Singh, a practicing doctor and professor from Columbia University was attacked by a group of young men in upper Manhattan. It was unfortunately not the first such news story I was reading. The story stayed with me. It could have been me, or someone from my family.

In the following years, the prevalence of hate crimes had risen – and I was alarmed at the escalation in bullying in schools. I felt compelled to write a story that would address this, and help readers process the events going on around us.

At the time I also saw people coming out and speaking against hate and supporting each other. These positive voices gave me hope.

Count Me In is therefore an uplifting story, told through the alternating voices of two middle-schoolers, in which a community rallies to reject racism.

You’ve written both picture books and middle grade – how is the writing process different for each?

With picture books I have help from a partner, the illustrator. We bring the characters and the story to life together. In my latest picture book, The Home Builders, I didn’t even name The Home Builders, till the babies are born. I didn’t need to. The illustrator, Simona Mulazzani did it for me.

With middle grade books, it’s my words alone that have to go forth and make the characters breathe and the story feel real.

Count Me In features a heartwarming intergenerational friendship. Is that something you particularly wanted to include and why?

I wanted to highlight the difference in perspectives within immigrant families. Papa is the immigrant and his generation’s thoughts and actions are different from Karina, who is born in America. Generations have so much to give each other. Their stories, their experiences and their viewpoints. When I visit schools and interact with children, I grow as a person.

What do you hope readers will take away from reading Count Me In?

This book is an open letter to America and the values and ideals it embodies. I remember watching President Obama speak at the DNC in 2004 when he said that “in no other country on earth is my story even possible.” His story, he said, was possible in a “tolerant” and “generous” America.

I hope readers realize that each one of us can make a difference to make sure that this country continues to live up to its ideals.

Tell us a little about how the wonderfully diverse cover came to be!

The cover is magnificent and the work of the talented Eleni Kalorkoti (www.elenikalorkoti.com). Without giving away the story, it looks a whole lot like a project that Karina and Chris undertake.

All those beautiful faces reflect the diversity of my community, my city, and of America.

Karina and Chris show us how a few voices can make a difference. What are the things that give you hope about this generation?

Having both Chris and Karina’s voices tell the story was so important to me because it was yet another way to show different perspectives. The younger generation in most cities and towns in America has only known a diverse student body. They have grown up eating different foods, they have been exposed to different music, and cultures through social media. When I see not only their acceptance of their diverse reality, but their excitement at its richness, it makes me happy. When I see the courage of young people like Malala and others it is inspiring.

Varsha Bajaj(varshabajaj.com) also wrote the picture books The Home BuildersandThis Is Our Baby, Born Today (a Bank Street Best Book). She grew up in Mumbai, India, and when she came to the United States to obtain her master’s degree, her adjustment to the country was aided by her awareness of the culture through books. In addition to her previous picture books, she wrote the middle-grade novel Abby Spencer Goes to Bollywood, which was shortlisted for the Cybils Award and included on the Spirit of Texas Reading Program. She lives in Houston, Texas.

Editorial Assistant, Graphix/Scholastic

Books have ruled my life since birth. I can’t remember a time that I wasn’t carrying either a novel or a journal in hand. There’s a picture of me at my sister’s high school graduation, holding Goblet of Fire,which I was re-reading for the millionth time during the ceremony. This image about sums me up.

So when the time came to choose a college major, naturally, I chose biology.

Confused? So was I.

But the reality is that, like many of us who grew up in the farthest, intimate little pockets of the country, growing up in Texas, I hadn’t heard a single thing about the possibility of publishing as a career option. To add to this, I was born to Indian immigrants who’d rather I pursued the straightforward life of a doctor or lawyer.

I got lucky. I had a sister who paved the way (edit: went to war) for me and chose an equally unique career path for herself. So when my time came around, my parents were skeptical, but willing to listen, especially when I didn’t shut up about it for the years to come. Unable to let the possibility of working with books go, and aware that I was about to begin an arduous, and possibly fruitless, journey, I wheedled my way into an internship with a local magazine with a tiny print run, and an office that was crammed with all sorts of strange antiques and Texan memorabilia. I’m forever grateful for that job, because the team had so much faith in me and gave me responsibilities far above my title. The following year, I made the insane choice to take on two unpaid internships in one semester; one at a larger magazine where I was one of many minions, and the second at a tiny indie publishing house.

As graduation neared, I pondered over my next step. Part of me dabbled with the idea of teaching English abroad for a year or two, maybe in Japan or Russia, but without any savings, that idea seemed far-fetched and fantastical. Even more fantastical was the thought that I’d land a coveted job at a publishing house straight out of school. Instead, I spent all of May begging the staff at my local Barnes & Noble for a job, despite the fact that they weren’t hiring at the time. Finally, they yielded. (The manager who hired me told me multiple times that she appreciated how proactive I was about getting a position there.) The four months I spent there were absolutely invaluable.

When September reared its ugly head, I decided that the entire month would be dedicated to job applications. I sat in the public library every day after work and worked until my eyes blurred. After about the 100th application, I got called in for an interview—at Penguin Random House, in New York City. I was astonished. And beyond excited. I booked a roundtrip flight, a room in Crown Heights, and carefully ironed my suit. I rode the subway during rush hour the morning of, met with HR and the hiring manager, and was out the door and on my way to the airport just a few hours later. On the flight back, I realized that the job just wasn’t a good fit. I had a feeling I wouldn’t be receiving an offer. Just as we were preparing for takeoff, my phone buzzed with an e-mail. The team at Cambridge University Press, also in NYC, wanted to meet me—tomorrow!

Luckily, they were kind enough to conduct a phone interview the next day instead—and I received my offer letter just three hours later, standing behind the register at Barnes & Noble. I’ve never screamed louder or jumped higher in public—and the best part? All of my B&N colleagues were jumping right alongside me.

Since my role at CUP, I’ve worked at Penguin Random House, and am currently at Scholastic, where I have the unbelievable pleasure of working on children’s graphic novels. Truth is, publishing isn’t for the faint of heart, and there are so many barriers in place for those from marginalized backgrounds. My parents still aren’t quite sure what I’m doing, but they’re supportive, and I’m exceedingly privileged to have that support. But if your path feels unconventional and messy, relish it—that’s what makes it yours. And don’t worry, there’s room to falter. Just don’t stray far. The road ahead may seem boundless, but you’ll get there, eventually.

Akshaya Iyer is an Editorial Assistant at Scholastic/Graphix where she works with a stupendous team and incredibly talented creators on the best children’s graphic novels in the industry. (She may be biased.)

She was born in the Midwest, raised in the South, and is now settled in the Northeast where she wonders if she’ll ever get used to the bitter cold.

By K-Fai Steele

A Normal Pig is a picture book about a pig named Pip. Pip considers herself to be a “pretty normal pig” who “does normal stuff.” But when a new pig shows up at her school and makes fun of Pip’s lunch, her identity—and sense of normalcy—is turned upside down.

A Normal Pig is somewhat autobiographical: I grew up in a town with little diversity and my parents are of different ethnicities. If physically standing out wasn’t enough, no one else had the same seemingly unpronounceable names as me and my brothers, and I have yet to meet another person who shares any of our names. There was little else I wanted as a kid than to pass as normal; I wanted a normal name, a normal house, and normal parents who had normal

well-paying jobs and drove nice normal cars. I internalized and accepted that I was not typical, a reality that was reinforced regularly by my school and my community.

One specific thing that I wanted to show Pip experiencing in A Normal Pig are microaggressions; the subtle, and often unintended ways that people who don’t fit into a community’s dominant paradigm are discriminated against. In Pip’s world she experiences microaggressions when her classmate loudly makes fun of her “weird” food, and later when her band teacher asks if her mom is her babysitter. These small comments reinforce stereotypes and have cumulative

effect; they identify someone as an outsider and tell them in many different ways that they don’t belong.

MakingA Normal Pig gave me the opportunity as an author-illustrator to directly challenge and dissect the concept of normal. I write in order to understand, and much of my process in making this picture book involved asking questions like: what is normal? Who gets to decide what normal means? Being one of the “only ones” in your community can be a deeply lonely and fraught experience; you may spend a lot of your energy coping, and you may lack the tools to challenge systems. My writing process started with reflecting on my own childhood experiences, then talking to friends and colleagues who had similar experiences and learning and reading a lot about people’s everyday experiences with discrimination, from critical race theory to short stories. The exciting thing is that I now get the opportunity to contribute back.

I think there’s a correlation between the immediacy of the themes in A Normal Pig to my drawing style and line (I used watercolor and ink). I’ve been told that my line carries boldness, humor, and sincerity. I use humor in visual and written storytelling as a tool to describe character responses to traumatic experiences, because that’s how I’ve personally processed similar experiences: they can be sad, funny, and awkward all at once.

I hope that many things about A Normal Pig resonate with readers! And specifically, I hope that readers use Pip’s story to question the very concept of the term “normal” and how that term can be used to include or exclude or split the world up into binaries that are deeply unnecessary and limited in regard to the richness of individual experience. Questioning things and getting opportunities to see the world from a different perspective can give you freedom and power, and that’s where we find Pip—and her friends—at the end of A Normal Pig: “weirdly enough, feeling pretty normal.”

K-Fai Steele is an author-illustrator who grew up in a house built in the 1700s with a printing press her father bought from a magician. She is currently a Brown Handler Writer in Residence at the San Francisco Public Library and is the 2019 James Marshall Fellow at the University of Connecticut. A Normal Pig is her author-illustrator debut with Balzer + Bray/HarperCollins Childrens. K-Fai lives in San Francisco.

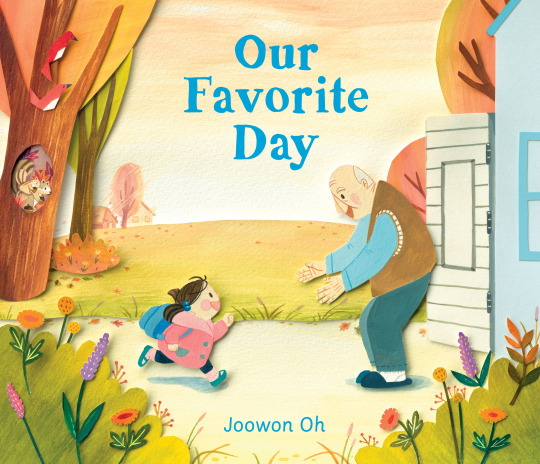

By Joowon Oh

Our Favorite Day is a book about the bond between Papa and his granddaughter.

Every morning, Papa starts his day by drinking some tea, watering his plants, and tidying up. Then he takes the bus into town to have his favorite lunch — dumplings! Papa enjoys his daily tasks, but Thursdays are his favorite, because that’s the day his granddaughter visits him. On that day, he buys some art supplies from the craft store, gets two orders of dumplings to go, and picks some flowers that he sees along the path. When his granddaughter finally arrives, they spend time together sharing dumplings, tiding up, doing arts and crafts, and flying a kite they make.

This tale of a grandfather’s love for his granddaughter was inspired by my childhood memories of my own grandfather. In the story, Papa and his granddaughter don’t live together, as I wanted their Thursdays to be particularly special, but my grandfather actually lived with my family until he passed away when I was eleven years old.

I have a lot of good memories with him, but the first thing that always comes to mind are the times we shared steamed dumplings in our dining room after school. After my grandmother passed away, my grandfather often had lunch alone at home or in the city, since my parents were at work and my siblings and I were at school. On the days he had dumplings for lunch in the city, he would bring some home for me and my siblings. When I got home from school, he would call me to our dining room and give me the dumplings to eat, sometimes wrapped in a napkin in his coat pocket. I think he did this out of habit: during the Korean War, food was very precious, and he may have saved leftovers like that then. I sometimes bit into a dumpling where a piece of napkin wasn’t peeled off properly, but I was never annoyed, because I knew that these dumplings were his love for us.

We would sit together, spending most of the late afternoons eating dumplings and talking about what I learned at school, how my exam went, what I did with my friends, and what my homework was for the next day. I loved those moments with him, not only because the dumplings were sweet, but also because I felt his love for me in the way he would look at me so endearingly while smiling tenderly. This may seem like a simple and insignificant detail in one’s childhood, but for me, it is a cherished moment that inspired me to write my very first children’s book about the special relationship between a grandparent and grandchild — and dumplings.

I started off by building Papa’s character, trying to visualize all the memories I had of my grandfather and jotting them down: wrinkles and age spots on his hands and face, gray hair, coat and knitted vest, cane, hat, shoes, slippers, pajamas, bedroom, plants, plant pots, hunched back, the way he walked, and so on. Then I set up Papa’s day, imagining what his routine would be by asking myself, What does he spend his time doing at home all alone? How does he get to the city? Where does he sit at the dumpling restaurant? Before his granddaughter comes home, what does he do to prepare for her?

In my initial story line, I wanted to show Papa’s loneliness while performing his daily routines, like when he is at home or eating alone at the restaurant, to contrast with his time with his granddaughter. However, my editor, Kate, suggested that it would be nice if I could create a community of people who care for and are interested in Papa and his life despite his living so quietly. We decided to add some dialogue with the waitress of the dumpling house and the craft shop owner to enhance the story, but also to ensure that Papa doesn’t seem like a lonely old man. I thought this was a great idea so that kids can see that their grandparents are people who can still enjoy their lives with their community and family.

The granddaughter is a sweet and creative little girl. She loves dumplings, polka dots, flowers, and drawing. She wants to make a butterfly kite instead of a traditional kite and decorates the string with the flowers that Papa picked for her. She is also a caring girl who likes to help Papa wash the dishes, thread a needle, and button his coat. Without her, the story cannot be complete. She is the reason that Papa looks forward to Thursdays.

In terms of the art-making process: After I received the revised text from my editor, my designer, Lauren, sent me an empty paging dummy with only the revised text and her and the editor’s notes about the illustrations on the bottom. Since the story had changed from my initial draft, I had to ignore most of the sketches in my old dummy and start all over again. I had to make thirty-two new sketches. At first, I thought this would be challenging, but I ended up enjoying the process.

First, I worked on the overall pacing of the story and the page layout. Since I wanted Papa’s typical day to move at a more leisurely pace in the beginning of the story, I drew only a single image or two on a page. Then when it was Thursday, I drew more panels per page to show how the pace of the story quickens as Papa has a lot to do in preparation for his granddaughter. For the scene where the granddaughter arrives, I drew a full spread because I wanted readers to pause to enjoy this big moment, the moment that the whole story has been building up to.

Then I tried drawing the scenes in different perspectives. They varied depending on what emotions and moments I wanted to convey through each scene. It was almost like filming a movie, with all the different angles. I kept asking myself, What perspective would be best to make readers feel as if they are watching Papa’s routines as observers? Should it be a high angle from above or a low angle to make Papa look small and weak compared to people passing by in the city? Should I zoom in on his hand and shoes instead of showing his whole body during the quiet moment when he bends down to pick flowers? I produced a couple of different sketches for each scene before deciding on a final composition.

While I was concentrating on depicting what was said in the text, I also had fun adding what was not said to make the illustrations more rich and to engage readers to open their imaginations. For example, in Papa’s bedroom, there is a photograph of Grandma wearing a polka-dotted dress and another of her holding a flower, two things that her granddaughter also likes. There is no explanation of what happened to Grandma, and I hope kids reflect on why the illustrator included photos of her in Papa’s bedroom, and also how he may feel when looking at these photographs.

To create the images, I used watercolor, white gouache, and colored paper. First, I sketched a scene on a lightweight paper and put watercolor paper on the top of the sketch. Then I traced some images out of the scene using a light box and painted them with watercolor mixed with white gouache. I cut out each image and put rolled tape on the back of the cutouts, then put it all together on a painted background. The reason I used rolled tape instead of glue was to create shadows underneath the cutouts and to make my artwork look more three-dimensional and tangible. It was a time-consuming process, but without it, I wouldn’t have been able to create the unique look.

Childhood doesn’t last forever, and the moments that kids can share with their grandparents are limited. Last week, I visited North Carolina to see my sister’s family, and my parents also came from Korea. My niece is almost two years old, and my nephew is five months old. I’m sure you can imagine how adoringly my parents look at their grandchildren. As I was watching my father play with his granddaughter, my giggling niece reminded me of myself and my father’s playful expression reminded me of my grandfather. I knew a grandchild could be the only one to bring out these emotions in my father. We all have childhood memories that will stick with us for the rest of our lives. They create who we are, shape our lives, help us find our purpose, and teach values. Even though my grandfather is no longer here and the dumpling restaurant no longer exists, the love and the warm memories that I was able to create with him have lasted. And as these memories have inspired me to write this book, I hope kids today will have great times with their grandparents, cherish every moment, and give the warmth they feel back to the world in their own ways.

Joowon Oh is originally from South Korea. She earned a BFA in illustration and an MFA in illustration as visual essay from the School of Visual Arts in New York. She works primarily in watercolor with a little bit of gouache and paper collage. Our Favorite Day is her picture book debut. She lives in New York City.

What are your literary influences?

My literary influences come from disparate sources. I studied a wide variety of theory in college and graduate school — everyone from Roland Barthes to Judith Butler to Gloria Anzaldua and Cherrie Moraga to Bell Hooks to Mikail Baktin to Subcomandante Marcos. I also read poetry voraciously including everyone from Waslowa Simbroska to Lorna Dee Cervantes, Audre Lorde, Rumi, Wole Soyinka, Juan Felipe Herrera. I was marveled by the fiction of Milan Kundera, Arundati Roy, Elena Poniatowska and all of the Latin American magical realists – Asturias, Garcia Marquez, Allende, Esquivel. But also, American writers such as Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, James Baldwin, Helena Maria Viramontes, Ana Castillo, Julia Alvarez and Christina Garcia. I was drawn to authors from the margin almost exclusively. In a sense, I created my own canon in this way.

It wasn’t until I became a mother that I truly started reading children’s literature. My children and I found an oasis in our weekly visits to the library. In Oakland, we are fortunate to have a comprehensive Spanish language collection at the Cesar Chavez Library and we often checked out the forty-book limit! However, many of the books were authored by non Latinx writers and were translated into Spanish. While these books served to reinforce the Spanish language in our family, I saw the huge lack of writings from Latinx creators. I wanted to be a part of filling that gap. I wanted for my children to not only see their language reflected in books but their cultures and their sensibilities. That is why I always praise the work of those Latinx authors who forged the way so that new Latinx kidlit authors could have a seat at the table. We stand on the shoulders of giants and I would be remiss if I didn’t mention their work. Authors such as Pura Belpre, Gary Soto, Sandra Cisneros, Alma Flor Ada, Pat Mora, Carmen Lomas Garza, Francisco X. Alarcon, Juan Felipe Herrera, and Victor Martinez really set the stage for us to be able to tell our stories to young audiences too.

What was the first book you read where you identified with one of the characters?

As a young child, I didn’t understand that I was missing in the narratives of books that I read. I loved Judy Blume. I loved Shell Silverstein. I loved Encyclopedia Brown and Choose Your Own Adventure books. I connected to those books by default, in a similar way that I connected to mass media that also didn’t include me in their blond-haired blue-eyed middle-class, English-only narratives. There was no other option. It wasn’t until I was eighteen and in college that I enrolled in a Latino (we called it that back then) literature course that I saw myself reflected in a book. I remember reading the short story “My Lucy Friend That Smells Like Corn,” in Sandra Cisneros’ Woman Hollering Creek and feeling a moment that I can only describe as grace. I realized that I had been missing in almost everything I had read up until that point. My experiences were alive and validated in that story. It was exhilarating.

Did that experience lead you to want to write books for readers with diverse backgrounds?

I was so inspired by reading all of the books in that Latino literature class. It was an awakening not only to the world of Latinx literature but to the possibility that I too could be a writer. I had been writing poetry and stories since I was a young teenager but those writings remained in my notebooks and journals. After reading their work, I began to take myself seriously and began to understand the writing that lived in my heart could be something I could aspire to do as a living someday. However, my awakening is one that should have not taken eighteen years and I want to be part of making sure that doesn’t happen to other children.

Your characters in The Moon Within have interesting intersections. Could you speak to why this was important to build into your book?

I did this intentionally. My children are multi-racial and bi-cultural like two of the characters, Celi and Iván. It is not uncommon to see many different mixed children in the San Francisco Bay Area where we live. I find it beautiful how they navigate multiple cultures – sometimes with a sense of wonder and pride and sometimes with neglect or shame and every feeling in between. It’s complicated and certainly isn’t always seamless given so much discussion over racial and cultural purity that is happening today. Through those characters, I wanted to show this negotiation, how they deal with these fusions. I wanted to show readers what it might look like for someone to celebrate and embrace all of who they are. Similarly, I wanted to show with the gender fluid character, Marco, the intersectionality of his identity as a gender fluid Mexican that happens to be in love with playing bomba (a Afro-Puertorican form of music). It was important to show readers that we could be queer and Mexican, Black Puerto Rican Mexican, and Black and Mexican. The range of identities are part of the beauty of who they are, and serve to strengthen and not weaken them.

Music infuses the whole world of The Moon Within …can you speak a little on that, a little on what role music plays in your own life?

Ironically, I am not a musician though I have a good ear and I love to dance. I am married to a musician and there has not been one day in the eighteen years since we’ve been together when we did not engage in some way with music – listening, playing, singing, dancing or just being in a house filled with instruments and an extraordinary recorded music collection. Our children were naturally born into this environment and took to music right away. I realized that this was a unique experience and that it could be a wonderful world to explore in this book. I wanted to normalize music and the arts as a way of life but also, wanted to inspire readers to seek out the arts as a way to find agency as the children in the book did through traditional music and dance. These are superpowers that unfortunately, with the cutting of the arts for decades now, we don’t have access to as much.

I made a playlist on Spotify that includes all of the styles of music that inspired The Moon Within – bomba, indigenous Mexican music, Caribbean music, and lots of moon related songs in Spanish and in English. It can be found here: https://spoti.fi/2FSnZgM . I hope that you enjoy it!

This Author Spotlight appeared in the April 2019 issue of the CBC Diversity Newsletter. To sign up for our monthly Diversity newsletter click here.

Aida Salazar is a writer, arts advocate, and home-schooling mother who grew up in South East LA. She received an MFA in Writing from the California Institute of the Arts, and her writings have appeared in publications such as the Huffington Post, Women and Performance: Journal of Feminist Theory, and Huizache Magazine. Her short story, By the Light of the Moon, was adapted into a ballet by the Sonoma Conservatory of Dance and is the first Xicana-themed ballet in history. Aida lives with her family of artists in a teal house in Oakland, CA.

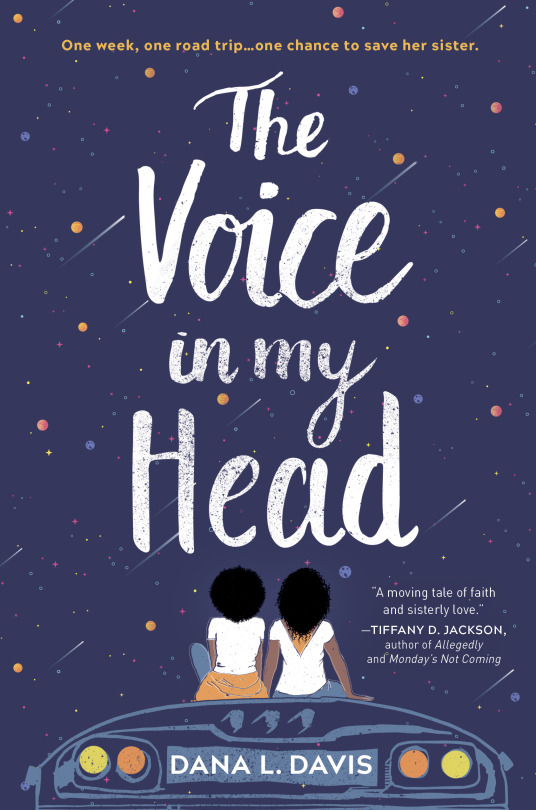

In your new book, THE VOICE IN MY HEAD , your main character is having conversations with God. And God sounds like…Dave Chapelle?

The short answer here is… kinda! God is patterned after Dave Chapelle’s sarcastic wit. In fact, when my main character, Indigo explains to her family what “God” sounds like, she says, “Well…he sounds a bit like Dave Chapelle.”

I can explain! One of the themes in THE VOICE IN MY HEAD is opening up our minds to a new concept of God. For so long we’ve all imagined this white faced God with a long beard, sitting on a throne, holding a scepter, doling out blessings and punishments. How droll! I think as we evolve as a race of beings, we have to have our perceptions about God and spirituality evolve too. I wanted to create the kind of God I’d want to talk to. And I’ve always admired Dave Chapelle. Not just for being funny, but for being wise and intelligent and inspiring. It’s like that song by Joan Osborne, What if God Was One of Us? I love those lyrics. I wanted to create a “God” like us. So yeah…in this book “God’s” gonna make you laugh, not cower in fear. But more importantly “God’s” gonna open up your mind and help you realize that perhaps you’re the power you seek.

It’s 100 years from now. How do you want to be remembered as a writer?

This question is everything! One I think all authors should seriously ask themselves before they write another word. I want to be remembered as a person who stopped complaining about how people of color were being represented in film and TV and in literature and who decided to do something about it. I want to be remembered as an author who worked hard to normalize the black experience. In 100 years, there will no longer be a go to narrative for black stories. I want to be remembered as an author who contributed to the new movement.

What’s your author pet peeve? Like…what really drives you crazy about the publishing world right now?

Comparison! I think platforms like Goodreads have given people a voice to say things like… “It wasn’t as good as (insert an entirely different book by an entirely different author with an entirely different life experience).” Look…don’t do that! If a book doesn’t resonate with you, don’t waste your time reading it! But for the love of everything good and pure, don’t read a book and then find an online platform to state… “Well…it wasn’t as good as this other book I read!” There are authors who create these lush, literary masterpieces and I read their works and I cry and I’m transformed and I see the world differently. There are other authors who create a laugh out loud, wild experience and I love it. Another author might create a sexy, fun love story. I can’t compare the lush, literary work that changed my life to the sexy rom com that made me not wanna be single. It’s not fair to authors. We have to stop comparing and allow authors to feel good about exactly where they are in their journey as a writer.

What’s your all time favorite book. Like…ever.

WHAT DREAMS MAY COME by Richard Matheson. This book wasn’t just spun from the author’s imagination. I mean…many parts were. But he compiled a ton of research on near death experiences and really took his time to compose such a beautiful story. I found so much truth in it. It truly changed my life and gave me a lot of peace about life on the other side. Glad I’m talking about it now because it’s one of those books you really should read more than once. I’d love to read it again someday. The movie that’s based on the book is interesting and I certainly enjoyed that too. But the book is truly a work of art.

Your first book TIFFANY SLY LIVES HERE NOW was about family. THE VOICE IN MY HEAD is about family too. What gives with all the family?

I’m all about breaking down stereotypes and normalizing the black experience. We don’t always have to be what you think we should be. We are princesses, queens, lovers, haters, doctors, lawyers, teachers. We are laughing ‘til our eyes water with tears, we are hanging out with friends. We are anything and everything you can imagine. In order for me to help people to truly understand that the black experience is just like any experience, I decided family is a great place to start. Families are the building blocks of who we are and who we become.

What makes you sad? What makes you happy?

I’m still living with anxiety…that makes me sad. It’s a tough road to travel. It’s heartbreaking at times. One of the things I miss is reading for enjoyment. My anxiety makes it nearly impossible to read. I also find it tough to focus on TV, so I don’t watch much of that. I had a blast writing TIFFANY SLY LIVES HERE NOW because it helped me to share a bit about the experience of living with anxiety. What makes me happy? Seeing the people I love succeed. Whatever success is to them. There is nothing better than celebrating a friend. Seeing their dreams come true.

What’s next?

More books! It was actually just announced that Inkyard Press acquired rights to my THIRD young adult novel Roman and Jewel. It’s a “witty, modern and unforgettable take on the classic star-crossed lovers story with a divers cast of characters.” I can’t wait to share it with the world. I feel like I came to Earth specifically to write this book! Ha. Can you tell I’m excited about it?!

Dana L. Davis is an actress who lives and works in LA. She has starred in Heroes,Prom Night,Franklin & Bash, and 10 Things I Hate About You. Dana is the founder of the Los Angeles-based nonprofit Culture for Kids LA, which provides inner-city children with free tickets and transportation to attend performing-arts shows around LA County. She currently stars in the following animated series: Star vs. the Forces of Evil,Craig of the Creek, and She-Ra.

Tell us about your most recent book and how you came to write/illustrate it.

All-American Muslim Girl is a YA novel born of my own experiences as a white-passing mixed-race Muslim in Georgia. I’m the daughter of a Jordanian-Circassian father and a blond Catholic cheerleader from Florida who converted to Islam when she and my dad got married. Most people have an image in their minds when they hear the words ‘Muslim girl’—and it’s definitely not me. As a result, I was exposed to a lot of harmful stealth Islamophobia over the years, moving unnoticed through predominantly white spaces as guards were down and people dropped casually bigoted comments. Post Trump, that stealth Islamophobia became blatant. I felt compelled to write an Islam-positive story of a young girl who, like me, initially struggles with a lack of connection to her religion but eventually chooses to actively embrace it, exploring how that affects her relationships along the way.

Do you think of yourself as a diverse author/illustrator?

I’ve always had lot of anxiety about my identity, something I address in AAMG (and tried to work through, in my MC of Allie Abraham!) On the one hand, I grew up feeling very much like an outsider, no matter what room I was in. When I was out with my visibly foreign father or my hijabi family members, the reception was noticeably different to what I’d get when out alone with my Barbie-esque mom. People would make fun of my last name (an impossible to pronounce Circassian name rife with consonants). Faces would change when they found out my family’s religion or background. But, on the other hand, my experience as a Muslim has still been very different from those of my Muslim friends and family members—to say nothing of my Brown and Black Muslim sisters. My lighter skin and ability to “pass” as a basic blonde has shielded me from the worst Islamophobia—something I am both grateful for and, honestly, a little ashamed of.

Who is your favorite character of all time in children’s or young adult literature?

It’s a four-way tie between Ramona Quimby, Anne Shirley, Jo March, and Hermione Granger. Feisty young women for the win!

Hypothetically speaking, let’s say you are forced to sell all of the books you own except for one. Which do you keep?

Oh my goodness! Okay, well, since this is purely hypothetical, I’m going to pretend we’re only talking about fiction books. From there…oof. When my husband and I got married, we thinned out our respective book collections, and it was torture. My answer would probably change depending on my mood, but for right now, I’d say my most dog-eared, weather-beaten book: an ancient, well-loved Norton Anthology of Poetry that I’ve had since I was 14. Barring that, my Harry Potter series, which I’m saving to read with my daughter when she’s old enough.

What does diversity mean to you as you think about your own books?

I feel like there’s often this checklist mentality toward diversity in literature, and it comes across as not only inauthentic but completely harmful. To me personally, diversity is about moving past seeing white as a default and not prioritizing the white gaze. It’s about recognizing that our stories are better when they reflect the world as it really is, in all its complexity. When you’re a marginalized teenager, maybe somebody who’s occasionally ill at ease around your peers, books can be your safe haven—a place where you can lose yourself and forget about whatever issues you’re going through, if briefly. Now imagine you read a book and it’s you, your life, your experiences reflected back on the page. How much less alone might you feel? How meaningful is that for a young person—questioning themselves, questioning their place—to realize there are others out there like them? That’s why I think it’s so important to not have publishing continue to churn out the same perspectives, the same heroes and heroines. Those stories have been told. Let’s shine the light elsewhere for a while and see what blooms.

What is your thought process in including or excluding characters of diverse backgrounds?

ForAll-American Muslim Girl, it was important to me to include Muslims from a variety of backgrounds, races, and ethnicities—because that’s the reality of Islam. It’s not just Arab Muslims, which is the default in the media. It’s Indonesian Muslims and Black Muslims and Desi Muslims and Muslim converts. I’m a Circassian Muslim, so though I’m fair like a lot of Muslims from the Caucausus region, my family have been Muslims for generations. I wanted to show not just that diversity of background, but also of thought: the book is full of a variety of young Muslim women who interpret the religion in vastly different ways and enjoy respectfully debating those disparate views. The Ummah is stronger and richer not in spite of our differences but because of them.

Nadine Jolie Courtney is the author of the upcoming YA novel All-American Muslim Girl (November 12, 2019, FSG), as well as the YA novel Romancing the Throne, and two adult books: Confessions of a Beauty Addict, and Beauty Confidential. A graduate of Barnard College, her articles have appeared in Town & Country, Angeleno, OprahMag.com, and Vogue.com. She lives in Santa Monica, California, with her family.

Website:nadinejoliecourtney.com; Instagram: @nadinejoliecourtney; Twitter: @nadinecourtney