#dianagabaldon

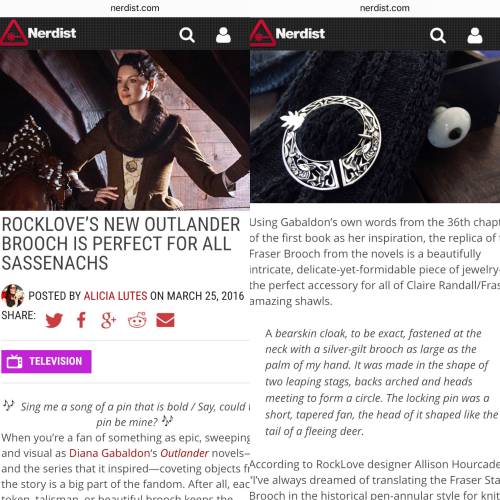

Keep your kilts on (this traditional brooch will help)… OUTLANDER Season 2 is nearly here!

Inspired by the enthralling prose of author Diana Gabaldon, the Fraser Stag Brooch AVAILABLE HERE.

A thunderous thanks to Alicia Lutesat@nerdist for the lovely FEATURE!

Post link

Episode 115: An interview with Allison Hourcade of @rocklovejewelry

Link: outlanderpod.com/115

Listen to me wax poetic about work with Outlander, RockLove’s collaborative merch process, an embarrassing interaction with Diana Gabaldon, and my racy teenage reading habits!

Once again @romasars managed to beautifully transfer my work on silk and create wonderful piece of wearable Outlander illustration. I’m sooo in love with it! It’s soft and light (but also very warm, believe me!). And you have no idea what I went through to give you a decent photo of the scarf - it’s a big piece of silk;). And if you want to spoil yourself or someone you love with it , check out Roma’s etsy store: https://www.etsy.com/shop/OutlanderScarvesArt

She makes them with a lot of love and attention to detail❤️

#outlander #outlanderart #outlanderfanart #scarf #silk #silkscarf #wearableart #jamiefraser #clairefraser #jamieandclaire #dianagabaldon #outlanderquotes #etsy

Post link

What is one book you know you’ll love, but can’t find the time to read it?

.

Jamie and Claire

Happy Wednesday bookstagram! I am going to get so much done today I hope. I only work for like 4 hours and the rest of my day I am free to read, take photos, enter rep searches that I want to enter, etc…

I still haven’t read outlander but I watched the first season of the tv show I know I’m awful! I’ve actually been to one of the castles they filmed in when I went to Scotland in 2015.

.

.

#julyofdisney

Brave- courageous character

#stuffandhogwartsjuly

Time turner- time/era you’d belong in

#book #books #bookworm #bookblog #bookstagram #bookblogger #bookphoto #bookjunkie #bookcovers #booklove #bookaholic #bookaddict #historicalfiction #bookcommunity #bookstagramchallenge #photochallenge #bookphotochallenge #outlander #dianagabaldon #bibliophile #instabook

Post link

There aren’t any answers, only choices

– Diana Gabaldon, Dragonfly in Amber (Outlander, #2)

#outlander #bookstagram #booklover #booksbooksbooks #dianagabaldon #dragonflyinamber

https://www.instagram.com/p/CCUXQ0hpyeC/?igshid=1ufweskanfo8s

Post link

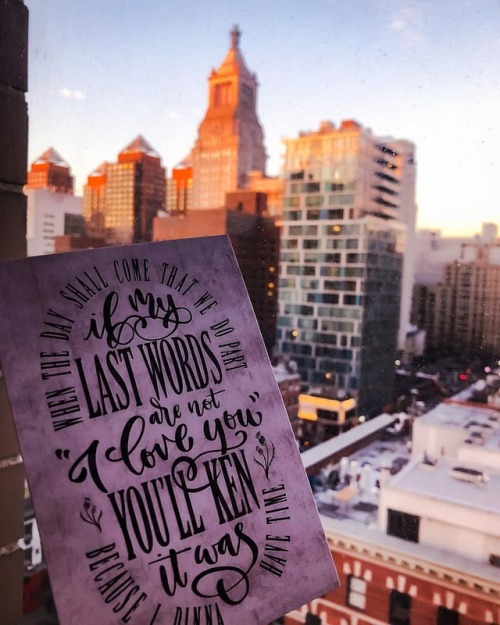

✨ Sneak peak of the February @nerdy.post box!! This gorgeous #Outlander print makes my heart ache, and so does this view, in the best way possible! Also, you can use my code PAGES10 for a few more days to save on your order from @nerdy.post!

✨✨✨✨

How are you guys doing? My midterms start this week so I’m pretty stressed, but by the end of next week I’ll be visiting home which I’m really excited about! Yay for Spring Break!

•

•

•

•

#books #bookish #bookstagram #bookphotography #nerdypost #nyc #newyork #manhattan #newyorkcity #skyline #dianagabaldon #bookart #bibliophile #booklover #bookworm #booknerd #booknerdigans #fantasy #lifestyle #homedecor #lifestyleblogger #bookblogger #art #epicreads #igreads (at New York University)

Post link

Lord John Grey was a surprise a surprise. She had heard her mother speak of John Grey—soldier, diplomat, nobleman—and expected someone tall and imposing. Instead, he was six inches shorter than she was, fine-boned and slight, with large, beautiful eyes, and a fair-skinned handsomeness that was saved from girlishness only by the firm

set of mouth and jaw.

He had looked startled upon seeing her; many people did, taken aback by her size—but then had set himself to exercise his considerable charm, telling her amusing anecdotes of his travel, admiring the two paintings that Jocasta had hung upon the wall, and regaling the table at large with news of the political situation in Virginia.

What he did not mention was her father, and for that she was grateful.

He turned to me, wordless, with a quiet ferocity that I might have thought the hunger of desire long stifled—but knew now for simple desperation. I sought no pleasure for myself; I wanted only to give him comfort. But opening to him, urging him, some deep wellspring opened too, and I cleaved to him in a sudden need as blind and desperate as his own.

We clung tight together, shuddering, heads buried in each other’s hair, unable to look at each other, unable to let go. Slowly, as the spasms died away, I became aware of things outside our own small mortal coil, and realized that we lay in the midst of strangers, naked and helpless, shielded only by darkness.

And yet we were alone, completely. We had the privacy of Babel; there was a conversation going on at the far end of the longhouse, but its words held no meaning. It might as well have been the hum of bees.

Smoke from the banked fire wavered up outside the sanctuary of our bed, fragrant and insubstantial as incense. It was dark as a confessional inside the cubicle; I could see no more of Jamie than the faint curve of light that rimmed his shoulder, a transient gleam in the locks of his hair.

“Jamie, I’m sorry,” I said softly. “It wasn’t your fault.”

“Who else?” he said, with some bleakness.

“Everyone. No one. Stephen Bonnet, himself. But not you.”

“Bonnet?” His voice was blank with surprise. “What has he to do with it?” “Well…everything,” I said, taken aback. “Er…doesn’t he?”

He rolled halfway off me, brushing hair out of his face.

“Stephen Bonnet is a wicked creature,” he said precisely, “and I shall kill him at the first opportunity I have. But I dinna see how I can blame him for my own failings as a man.”

“What on earth are you talking about? What failings?”

He didn’t answer right away, but bent his head, a humped shadow in the dark. His legs were still entangled with mine; I could feel the tension of his body, knotted in his joints, rigid in the hollows of his thighs.

“I hadna thought ever to be so jealous of a dead man,” he whispered at last. “I shouldna have thought it possible.”

“Of a dead man?” My own voice rose slightly, with astonishment, as it finally dawned on me. “Of Frank?”

He lay still, half on top of me. His hand touched the bones of my face, hesitant.

“Who else? I have been worm-eaten wi’ it, all these days of riding. I see his face in my mind, waking and sleeping. Ye

did say he looked like Jack Randall, no?”

I gathered him tight against myself, pressing his head down so that his ear was near my mouth. Thank God I hadn’t

mentioned the ring to him—but had my face, my traitorous, transparent face, somehow given away that I thought of it? “How?” I whispered to him, squeezing hard. “How could you think of such a thing?”

He broke loose, rising on one elbow, his hair falling down over my face in a mass of flaming shadows, the firelight

sparking gold and crimson through it.

“How could I not?” he demanded. “Ye heard her, Claire; ye ken well what she said to me!”

“Brianna?”

“She said she would gladly see me in hell, and sell her own soul to have her father back—her real father.” He swallowed; I heard the sound of it, above the murmur of distant voices.

“I keep thinking he would not have made such a mistake. He would have trusted her; he would have known that she…I

keep thinking that Frank Randall was a better man than I am. She thinks so.” His hand faltered, then settled on my shoulder, squeezing tight. “I thought…perhaps ye felt the same, Sassenach.”

“Fool,” I whispered, and didn’t mean him. I ran my hands down the long slope of his back, digging my fingers into the firmness of his buttocks. “Wee idiot. Come here.”

He dropped his head, and made a small sound against my shoulder that might have been a laugh.

“Aye, I am. Ye dinna mind it so much, though?”

“No.” His hair smelt of smoke and pinesap. There were still bits of needles caught in it; one pricked smooth and sharp

against my lips.

“She didn’t mean it,” I said.

“Aye, she did,” he said, and I felt him swallow the thickness in his throat. “I heard her.”

“I heard you both.” I rubbed slowly between his shoulder blades, feeling the faint traces of the old scars, the thicker,

more recent welts left by the bear’s claws. “She’s just like you; she’ll say things in a temper she’d never say in cold blood. You didn’t mean all the things you said to her, did you?”

“No.” I could feel the tightness in him lessening, the joints of his body loosening, yielding reluctantly to the persuasion of my fingers. “No, I didna mean it. Not all of it.”

“Neither did she.”

I waited a moment, stroking him as I had stroked Brianna, when she was small, and afraid.

“You can believe me,” I whispered. “I love you both.”

He sighed, deeply, and was quiet for a moment.

“If I can find the man and bring him back to her. If I do—d’ye think she’ll forgive me one day?”

“Yes,” I said. “I know it.”

On the other side of the partition, I heard the small sounds of lovemaking begin; the shift and sigh, the murmured

words that have no language.

“You have to go.” Brianna had said to me. “You’re the only one who can bring him back.” It occurred to me for the first time that perhaps she hadn’t been speaking of Roger.

Diana Gabaldon

Drums Of Autumn

Escape. It would be that. Escape to when, though? And how? The words of Geilie’s spell chanted in his mind. Garnets rest in love about my neck; I will be faithful.

Faithful. To try that avenue of escape was to abandon Brianna. And hasn’t she abandoned you?

“No, I’m damned if she has!” he whispered to himself. There was some reason for what she’d done, he knew it. She’s found her parents; she’ll be safe enough. “And for this reason, a woman shall leave her parents, and cleave to

her husband.” Safety wasn’t what mattered; love was. If he’d cared for safety, he wouldn’t have crossed that desperate void to begin with.

His hands were sweating; he could feel the damp grain of the rough cloth under his fingers, and his torn fingertips burned and throbbed. He took one more step toward the split in the cliff face, his eyes fixed on the pitch-black inside. If he didn’t step inside…there were only two things to do. Go back to the suffocating grip of the rhododendrons, or try to scale the cliff before him.

He tilted his head back to gauge its height. A face was looking down at him, featureless in the dark, silhouetted against the moon-bright sky. He hadn’t time to move or think before the rope noose settled gently over his head and tightened, pressing his arms against his body.

“Brianna,” he said quietly behind her. She didn’t answer, didn’t move. He made a small snorting noise—anger, impatience?.Say it,” she said, and the words hurt her throat, as though she’d swallowed some jagged object.

It was beginning to rain again; fresh spatters slicked the marble in front of her, and she could feel the icy pat! of drops

that struck through her hair.

“I will bring him home to you,” Jamie Fraser said, still quiet, “or I will not come back myself.”

Drums Of Autumn

Diana Gabaldon

“I thought of it,” she said, with a deep breath. “As soon as I realized. I wondered if you could do—something like that, here.”

“It wouldn’t be easy. It would be dangerous—and it would hurt. I don’t even have any laudanum; only whisky. But yes, I can do it—if you want me to.” I forced myself to sit still, watching her pace slowly back and forth before the hearth, hands folded behind her in thought.

“It would have to be surgical,” I said, unable to keep quiet. “I don’t have the right herbs—and they aren’t always reliable, in any case. At least surgery is…certain.” I laid the scalpel on the table; she should not be under any illusions as to what I was suggesting. She nodded at my words, but didn’t stop her pacing. Like Jamie, she always thought better while moving.

A trickle of sweat ran down my back, and I shivered. The fire was warm enough, but my fingers were still cold as ice. Christ, if she wanted it, would I even be able to do it? My hands had begun to tremble, with the strain of waiting.

She turned at last to look at me, eyes clear and appraising under thick, ruddy brows.

“Would you have done it? If you could?”

“If I could—?”

“You said once that you hated me, when you were pregnant. If you could have not been—”

“God, not you!” I blurted, horror-stricken. “Not you, ever. It—” I knotted my hands together, to still their trembling. “No,” I

said, as positively as I could. “Never.”

“You did say so,” she said, looking at me intently. “When you told me about Da.”

I rubbed a hand across my face, trying to focus my thoughts. Yes, I had told her that. Idiot.

“It was a horrible time. Terrible. We were starving, it was war—the world was coming apart at the seams.” Wasn’t

hers? “At the time, it seemed as though there was no hope; I had to leave Jamie, and the thought drove almost everything else out of my mind. But there was one other thing,” I said.

“What was that?”

“It wasn’t rape,” I said softly, meeting her eyes. “I loved your father.”

She nodded, her face a little pale.

“Yes. But it might be Roger’s. You did say that, didn’t you?”

“Yes. It might. Is the possibility enough for you?”

She laid a hand over her stomach, long fingers gently curved.

“Yeah. Well. It isn’t an it, to me. I don’t know who it is, but—” She stopped suddenly and glanced at me, looking

suddenly shy.

“I don’t know if this sounds—well…” She shrugged abruptly, dismissing doubt. “I had this sharp pain that woke me up

in the middle of the night, a few days…after. Quick, like somebody had stabbed me with a hatpin, but deep.” Her fingers curled inward, her fist pressing just above her pubic bone, on the right side.

“Implantation,” I said softly. “When the zygote takes root in the womb.” When that first, eternal link is formed between mother and child. When the small blind entity, unique in its union of egg and sperm, comes to anchor from the perilous voyage of beginning, home from its brief, free-floating existence in the body, and settles to its busy work of division, drawing sustenance from the flesh in which it embeds itself, in a connection that belongs to neither side, but to both. That link, which cannot be severed, either by birth or by death.

She nodded. “It was the strangest feeling. I was still half asleep, but I…well, I just knew all of a sudden that I wasn’t alone.” Her lips curved in a faint smile, reminiscent of wonder. “And I said to…it…” Her eyes rested on mine, still lit by the smile, “I said, ‘Oh, it’s you.’ And then I went back to sleep.”

Her other hand crossed the first, a barricade across her belly.

“I thought it was a dream. That was a long time before I knew. But I remember. It wasn’t a dream. I remember.”

I remembered, too.

I looked down and saw beneath my hands not the wooden tabletop nor gleaming blade, but the opal skin and perfect

sleeping face of my first child, Faith, with slanted eyes that never opened on the light of earth.

Looked up into the same eyes, open now and filled with knowledge. I saw that baby, too, my second daughter, filled

with bloody life, pink and crumpled, flushed with fury at the indignities of birth, so different from the calm stillness of the first—and just as magnificent in her perfection.

Two miracles I had been given, carried beneath my heart, born of my body, held in my arms, separated from me and part of me forever. I knew much too well that neither death nor time nor distance ever altered such a bond—because I had been altered by it, once and forever changed by that mysterious connection.

“Yes, I understand,” I said. And then said, “Oh, but Bree!” as the knowledge of what her decision would mean to her flooded in on me anew.

She was watching me, brows drawn down, lines of trouble in her face, and it occurred to me belatedly that she might.

take my exhortations as the expression of my own regrets.

Appalled at the thought that she might think I had not wanted her, or had ever wished she had not been, I dropped the

blade and reached out across the table to her.

“Bree,” I said, seized with panic at the thought. “Brianna. I love you. Do you believe I love you?”

She nodded without speaking, and stretched out a hand toward me. I grasped it like a lifeline, like the cord that had

once joined us.

She closed her eyes, and for the first time I saw the glitter of tears that clung to the delicate, thick curve of her lashes. “I’ve always known that, Mama,” she whispered. Her fingers tightened around mine; I saw her other hand press flat

against her stomach. “From the beginning.”

Drums Of Autumn

Diana Gabaldon

The night stood still around him, paused as time had paused so long before, poised on the edge of a gulf of dread, waiting. Waiting for the next words, known beforehand and expected, but nonetheless…

“And then,” the voice said, loving, “then I’ll hurt you very badly. And you will thank me, and ask for more.”

He stood quite still, face turned upward to the stars. Fought back the surge of fury as it murmured in his ear, the pulse of memory in his blood. Then made himself surrender, let it come. He trembled with remembered helplessness, and clenched his teeth in rage—but stared unblinking at the brightness of heaven overhead, invoking the names of the stars as the words of a prayer, abandoning himself to the vastness overhead as he sought to lose himself below.

Betelgeuse. Sirius. Orion. Antares. The sky is very large, and you are very small. Let the words wash through him, the voice and its memories pass over him, shivering his skin like the touch of a ghost, vanishing into darknes

The Pleiades. Cassiopeia. Taurus. Heaven is wide, and you are very small. Dead, but none the less powerful for being dead. He spread his hands wide, gripping the fence—those were powerful, too. Enough to beat a man to death, enough to choke out a life. But even death was not enough to loose the bands of rage.

With great effort, he let go. Turned his hands palm upward, in gesture of surrender. He reached beyond the stars, searching. The words formed themselves quietly in his mind, by habit, so quietly he was not aware of them until he found them echoed in a whisper on his lips.

“ ‘…Forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us.’ ”

He breathed slowly, deeply. Seeking, struggling; struggling to let go. “ ‘Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil.’ ”

Waited, in emptiness, in faith. And then grace came; the necessary vision; the memory of Jack Randall’s face in Edinburgh, stricken to bare bone by the knowledge of his brother’s death. And he felt once more the gift of pity, calm in its descent as the landing of a dove.

He closed his eyes, feeling the wounds bleed clean again as the succubus drew its claws from his heart.

He sighed, and turned his hands over, the rough wood of the fence comforting and solid under his palms. The demon was gone. He had been a man, Jack Randall; nothing more. And in the recognition of that common frail humanity, all power of past fear and pain vanished like smoke.

His shoulders slumped, relieved of their burden.

“Go in peace,” he whispered, to the dead man and himself. “You are forgiven.”

The night sounds had returned; the cry of a hunting cat rose sharp on the air, and rotting leaves crunched soft

underfoot as he made his way back toward the house. The oiled hide that covered the window glowed golden in the dark, with the flame of the candle he had left burning in the hope of Claire’s return. His sanctuary.

He thought that he should perhaps have told Brianna all this, too—but no. She couldn’t understand what he had told her; he had had to show her, instead. How to tell her in words, then, what he had learned himself by pain and grace? That only by forgiveness could she forget—and that forgiveness was not a single act, but a matter of constant practice.

Drums Of Autumn

Diana Gabaldon

Put your trust in God, and pray for guidance. And when in doubt, eat.” A Franciscan monk had once given me that advice, and on the whole, I had found it useful. I picked out a jar of black currant jam, a small round goat cheese, and a bottle of elderflower wine, to go with the meal.

Jamie was talking quietly when I came back. I finished my preparations, letting the deep lilt of his voice soothe me, as well as Brianna.

“I used to think of you, when ye were small,” Jamie was saying to Bree, his voice very soft. “When I lived in the cave; I would imagine that I held ye in my arms, a wee babe. I would hold ye so, against my heart, and sing to ye there, watching the stars go by overhead.”

“What would you sing?” Brianna’s voice was low, too, barely audible above the crackle of the fire. I could see her hand, resting on his shoulder. Her index finger touched a long, bright strand of his hair, tentatively stroking its softness.

“Old songs. Lullabies I could remember, that my mother sang to me, the same that my sister Jenny would sing to her bairns.”

She sighed, a long, slow sound.

“Sing to me now, please, Da.”

He hesitated, but then tilted his head toward hers and began to chant softly, an odd tuneless song in Gaelic. Jamie

was tone-deaf; the song wavered oddly up and down, bearing no resemblance to music, but the rhythm of the words was a comfort to the ear.

I caught most of the words; a fisher’s song, naming the fish of loch and sea, telling the child what he would bring home to her for food. A hunter’s song, naming birds and beasts of prey, feathers for beauty and furs for warmth, meat to last the winter. It was a father’s song—a soft litany of providence and protection.

I moved quietly around the room, taking down the pewter plates and wooden bowls for supper, coming back to cut bread and spread it with butter.

“Do you know something, Da?” Bree asked softly. “What’s that?” he said, momentarily suspending his song.

You can’t sing.”

There was a soft exhalation of laughter and the rustle of cloth as he shifted to make them both more comfortable. “Aye, that’s true. Shall I stop, then?”

“No.” She snuggled closer, tucking her head into the curve of his shoulder.

He resumed his tuneless crooning, only to interrupt himself a few moments later.

“D’ye ken something yourself, a leannan?”

Her eyes were closed, her lashes casting deep shadows on her cheeks, but I saw her lips curve in a smile.

“What’s that, Da?”

“Ye weigh as much as a full-grown deer.”

“Shall I get off, then?” she asked, not moving.

“Of course not.”

She reached up and touched his cheek.

“Mi gradhaich a thu, athair,” she whispered. My love to you, Father.

He gathered her tightly against him, bent his head and kissed her forehead. The fire struck a knot of pitch and blazed

up suddenly behind the settle, limning their faces in gold and black. His features were harsh-cut and bold; hers, a more delicate echo of his heavy, clean-edged bones. Both stubborn, both strong. And both, thank God, mine.

Drums of Autumn

Diana Gabaldon

What angel will free you from sadness

and you will wake up a beautiful day

without memory of what afflicted you

and he will whisper in your ear: “Listen and stop

your crying In my arms, it does not weigh you

the slowness of time nor the impious

betrayal of men. You’re mine,

you are no longer of this vain world prey.

Peek into this bright window

for your ornate happiness. Already the pain

it withered like a long flower

whose wisdom finally heals you

when it dissolves because it becomes

in dust, in illusion, in another fate ”.

Silvina Ocampo

“What does that mean—a leannan? And the other thing you said?”

“You’ll not have the Gaelic, then?” he asked, and shook his head. “No, of course she wouldna have been taught,” he murmured, as though to himself.

“I’ll learn,” she said firmly, giving her nose a last wipe. “A leannan?”

A slight smile reappeared on his face as he looked at her.

“It means ‘darling,’ ” he said softly. “M’ annsachd—my blessing.”

The thought of her mother was overwhelming. Her face cracked, and the tears she had been holding back for days spilled down her cheeks in a flood of relief, half choking her as she laughed and cried together.

“Here, lassie, dinna weep!” he exclaimed in alarm. He let go of her arm and snatched a large, crumpled handkerchief from his sleeve. He patted tentatively at her cheeks, looking worried.

“Dinna weep, a leannan, dinna be troubled,” he murmured. “It’s all right, m’ annsachd; it’s all right.”

#DianaGabaldon

#DrumsOfAutumn

He jerked back, and his face did change then, mask shattering in surprise. Without it, he looked younger; underneath

were shock, surprise, and a dawning expression of half-painful eagerness.

“Och, no, lassie!” he exclaimed. “I didna mean it that way, at all! It’s only—” He broke off, staring at her in fascination.

His hand lifted, as though despite himself, and traced the air, outlining her cheek, her jaw and neck and shoulder, afraid to touch her directly.

“It’s true?” he whispered. “It is you, Brianna?” He spoke her name with a queer accent—Breeanah—and she shivered at the sound.

“It’s me,” she said, a little huskily. She made another attempt at a smile. “Can’t you tell?”

His mouth was wide and full-lipped, but not like hers; wider, a bolder shape, that seemed to hide a smile in the corners of it, even in repose. It was twitching now, not certain what to do.

“Aye,” he said. “Aye, I can.”

He did touch her then, his fingers drawing lightly down her face, brushing back the waves of ruddy hair from temple and ear, tracing the delicate line of her jaw. She shivered again, though his touch was noticeably warm; she could feel the heat of his palm against her cheek.

“I hadna thought of you as grown,” he said, letting his hand fall reluctantly away. “I saw the pictures, but still—I had ye in my mind somehow as a wee bairn always—as my babe. I never expected…” His voice trailed off as he stared at her, the eyes like her own, deep blue and thick-lashed, wide in fascination.

“Pictures,” she said, feeling breathless with happiness. “You’ve seen pictures of me? Mama found you, didn’t she? When you said you had a wife at home—”

“Claire,” he interrupted. The wide mouth had made its decision; it split into a smile that lit his eyes like the sun in the dancing tree leaves. He grabbed her arms, tight enough to startle her.

“You’ll not have seen her, then? Christ, she’ll be mad wi’ joy!

Drums of Autumn

Diana Gabaldon

She’d wanted to go to the Christmas Eve services. After that…

After that, he would ask her, make it formal. She would say yes, he knew. And then…

Why, then, they would come home, to a house dark and private. With themselves alone, on a night of sacrament and secret, with love newly come into the world. And he would lift her in his arms and carry her upstairs, on a night when virginity’s sacrifice was no loss of purity, but rather the birth of everlasting joy.

DRUMS OF AUTUMN

Diana Gabaldon

chapter 17

“Home for the Holidays”.

#Outlander

Teach us to value eternal things above all

to find the joy hidden by generosity

to know the peace of distant hills

to experience the joy of giving of heart

to remember this Christmas that the only thing that can be preserved is what is given

Dear Friends #MerryChristmas

Is that a cairn?” she asked Ian, voice lowered in respect. Cairns were the memorials of the dead, her mother had told her—sometimes the very long dead—new rocks added to the heap by each passing visitor.

He glanced at her in surprise, caught the direction of her gaze, and grinned.

“Ah, no, lass. Those are the stones we turned up wi’ the plow in the spring. Every year we take them out, and every year there come new ones. Damned if I ken where they come from,” he added, shaking his head in resignation. “Stone fairies come and sow them in the night, I expect.”

She didn’t know whether this was a joke or not. Uncertain whether to laugh, she asked a question instead.

“What will you plant here?”

“Oh, it’s planted already.” Ian shaded his eyes, squinting across the long field with pride. “This is the tattie field. The

new vines will be up by the end of the month.”

“Tattie—oh, potatoes!” She looked at the field with new interest. “Mama told me about that.”

“Aye, it was Claire’s notion—and a good one, too. There’s more than once the tatties have kept us from starving.” He

smiled briefly but said nothing more, and moved off, heading for the wild hills beyond the fields.

It was a long walk. The day was breezy, but warm, and Brianna was sweating by the time they paused at last, halfway

up a rough track through the heather. The narrow path seemed to perch precariously between a steep hillside and an even steeper fall down a sheer rock face into a small, splashing burn.

Ian stopped, wiping his brow with his sleeve, and motioned her to a seat amid the heaps of granite boulders. From this vantage point, the valley lay below them, the farmhouse seeming small and incongruous, its fields a feeble intrusion of civilization on the surrounding wilderness of crag and heather.

He brought out a stone bottle from the sack he carried, and drew the cork with his teeth.

“That’ll be your mother’s doing, too,” he said with a grin, handing her the bottle. “That I’ve kept my teeth, I mean.” He passed the tip of his tongue meditatively over his front teeth, shaking his head.

“A great one for eatin’ weeds, your mother, but who’s to argue, eh? Half the men my age are eatin’ naught but porridge now.”

“She was always telling me to eat up my vegetables, when I was little. And brush after every meal.” Brianna took the bottle from him and tilted it into her mouth; the ale was strong and bitter, but welcomely cool after the long walk.

“When ye were little, eh?” Amused, Ian cast an eye over her length. “I’ve seldom seen a lass sae braw. I’d say your mother kent her business, aye?”

She smiled back and gave him back the bottle.

“She knew enough to marry a tall man, at least,” she said wryly.

Ian laughed and wiped the back of his hand across his mouth. He gazed affectionately at her, brown eyes warm.

“Ah, it’s fine to see ye, lassie. You’re verra much like him, it’s true. Christ, what I wouldna give to be there when Jamie

sees you!”

She looked down at the ground, biting her lip. The ground was thick with bracken, and their path up the hill showed

plain, where the green fronds that had overgrown the track had been crushed and knocked aside.

“I don’t know whether he knows or not,” she blurted. “About me.” She glanced up at him. “He didn’t tell you.”

Ian rocked back a little, frowning.

“No, that’s true,” he said slowly. “But I am thinking he maybe hadna time to say, even if he knew. He’ll not have been

here long, that last time he came, with Claire. And then, it was such a moil, wi’ all that happened—” He stopped, pursing his lips, and glanced at her.

Drums of autumn

Diana Gabaldon

Heads you live, and tails you die. A fair chance, would yez say, MacKenzie?”

“For them?”

“For you.”

The soft Irish voice was as unemphatic as it might be were it making observations of the weather.

As in a dream, Roger felt the weight of the shilling drop once more into his hands. He heard the suck and hiss of the

water on the hull, the blowing of the whales—and the suck and hiss of Bonnet’s breath as he drew on his cigar. Seven whales the fill of a Cirein Croin.

“A fair chance,” Bonnet said. “Luck was with you before, MacKenzie. See will Danu come for you again—or will it be the Soul-Eater this time?”

The fog had closed over the deck. There was nothing visible save the glowing coal of Bonnet’s cigar, a burning cyclops in the mist. The man might be a devil indeed, one eye closed to human misery, one eye open to the dark. And here Roger stood quite literally between the devil and the deep blue sea, with his fate shining silver in the palm of his hand.

“It is my life; I’ll make the call,” he said, and was surprised to hear his voice calm and steady. “Tails—tails is mine.” He threw, and caught, clapped his one hand hard against the back of the other, trapped the coin and its unknown sentence.

He closed his eyes and thought just once of Brianna. I’m sorry, he said silently to her, and lifted his hand.

A warm breath passed over his skin, and then he felt a spot of coolness on the back of his hand as the coin was picked up, but he didn’t move, didn’t open his eyes.

It was some time before he realized that he stood alone.

The second portrait hung on the landing of the stairs, looking thoroughly out of place. From below she could see the ornate gilded frame, its heavy carving quite at odds with the solid, battered comfort of the house’s other furnishings. It reminded her of pictures in museums; this homely setting seemed incongruous.

As she followed Jenny onto the landing the glare of light from the window disappeared, leaving the painting’s surface flat and clear before her.

She gasped, and felt the hair rise on her forearms, under the linen of her shirt.

“It’s remarkable, aye?” Jenny looked from the painting to Brianna and back again, her own features marked with something between pride and awe.

“Remarkable!” Brianna agreed, swallowing.

“Ye see why we kent ye at once,” her aunt went on, laying a loving hand against the carved frame.

“Yes. Yes, I can see that.”

“It will be my mother, aye? Your grandmother, Ellen MacKenzie.”

“Yes,” Brianna said. “I know.” Dust motes stirred up by their footsteps whirled lazily through the afternoon light from

the window. Brianna felt rather as though she was whirling with them, no longer anchored to reality.

Two hundred years from now, she had—I will? she thought wildly—stood in front of this portrait in the National Portrait

Gallery, furiously denying the truth that it showed.

Ellen MacKenzie looked out at her now as she had then; long-necked and regal, slanted eyes showing a humor that

did not quite touch the tender mouth. It wasn’t a mirror image, by any means; Ellen’s forehead was high, narrower than Brianna’s, and the chin was round, not pointed, her whole face somewhat softer and less bold in its features.

But the resemblance was there, and pronounced enough to be startling; the wide cheekbones and lush red hair were the same. And around her neck was the string of pearls, gold roundels bright in the soft spring sun.

“Who painted it?” Brianna said at last, though she didn’t need to hear the answer. The tag by the painting in the museum had given the artist as “Unknown.” But having seen the portrait of the two little boys below, Brianna knew, all right. This picture was less skilled, an earlier effort—but the same hand had painted that hair and skin.

“My mother herself,” Jenny was saying, her voice filled with a wistful pride. “She’d a great hand for drawing and painting. I often wished I had the gift.”

#Outlander #Brianna #Roger #CraighNaDun

“Such a mother, such a daughter” … the gifts are always inherited and the blood ties are never broken …

Throbbing the new episode #DownTheRabbitHole

She’d not reproached him. Not with that at least, he thought, suddenly remembering how she’d acted when she’d found out about Laoghaire. She’d gone for him like a fiend, then, and yet when later she’d learned about Geneva Dunsany…perhaps it was only that the boy’s mother was dead?

The realization went through him like a sword thrust. The boy’s mother was dead. Not just his real mother, who’d died the same day he was born—but the woman he’d called mother all his life since. And now his father—or the man he called father, Jamie thought with an unconscious twist of his mouth—was lying sick of an illness that had killed another man before the lad’s eyes no more than days before.

No, it wasn’t fright that made the lad greet by himself in the dark. It was grief, and Jamie Fraser, who’d lost a mother in childhood himself, ought to have known that from the beginning.

It wasn’t stubbornness, nor even loyalty, that had made Willie insist on staying at the Ridge. It was love of John Grey, and fear of his loss. And it was the same love that made the boy weep in the night, desperate with worry for his father.

An unaccustomed weed of jealousy sprang up in Jamie’s heart, stinging like nettles. He stamped firmly on it; he was fortunate indeed to know that his son enjoyed a loving relationship with his stepfather. There, that was the weed stamped out. The stamping, though, seemed to have left a small bruised spot on his heart; he could feel it when he breathed.