#english heritage

More than ever, we must remember our historic bond with Poland and Ukraine

More than ever, we must remember our historic bond with Poland and Ukraine

New discoveries by English Heritage shine a light on our three countries’ shared fight for freedom

Sir Tim Laurence for The Telegraph.

Written in pencil on the wall of the candle store at Audley End House in Essex is a list. In the shadows for decades, this unassuming scrawl has now been deciphered as the names of six Polish men. Research by English Heritage – who now take care of the House – has revealed who they were and why they were there.

They include a 43-year-old father of two, fluent in five languages; a highly strung army officer who loved horse riding; a teacher; a film star and two young men in their early twenties.

These men were members of a select group, trained to drop behind enemy lines into occupied Poland to fight for their homeland during WW2. For it was eighty years ago today, on 1 May 1942, that Audley End became the principal training school for the Cichociemni, the Polish section of the Special Operations Executive.

Their fascinating story of heroism and sacrifice resonates with the current terrible events in Ukraine. Changing political boundaries and the movement of peoples within Eastern Europe over the centuries mean there are deep connections between Poles and Ukrainians. Of the six men whose names are scratched in pencil onto the wall in the candle store, one, Karol Dorwski, came from Lviv and another, Franciszek Socha, studied at university there. The warm welcome Ukrainian refugees have received in Poland today speaks to these historic connections and also reflects the Poles’ collective memory of destruction and displacement during WW2.

Yet their ties also extend to Britain. Audley End was known as Special Training School (STS) 43. Those who trained there were elite special operations paratroopers. They arrived having already completed paramilitary and fitness courses in the Scottish Highlands and parachute training in Cheshire. Most had also done specialist courses in sabotage, weapons handling and signalling.

At Audley End they took two courses: Underground Warfare and Briefing. The former tested their physical fitness, mastery of weapons, use of explosives and demolitions, and skills in communications and irregular warfare. The house’s extensive grounds and relative privacy made it the ideal site for such exploits. The Briefing course occupied the last six weeks of training. Operatives concocted individual cover stories or ‘legends’, chose an alias and were given false documents and authentic Polish clothes. Those who successfully completed it took an oath of allegiance to the Polish Home Army (AK). They then waited in a holding station until selected for a mission in Poland.

2,613 Poles volunteered for special operations during the war, with 606 of them getting through the rigorous training course. 316 were later dropped into occupied Poland; the majority of them trained at Audley End.

These incredibly brave personnel were at the forefront of Polish resistance. Many became important staff officers in the AK, taking part in widespread partisan operations culminating in uprisings in Wilno, Lviv and Warsaw. 103 were killed in action or murdered by the Gestapo, and a further nine were executed by the Communists after the war.

Today, the Cichociemni are revered in Poland, with many commemorated with statues or plaques in their home towns. Their brave and heroic service inspired GROM, Poland’s modern special forces unit, to adopt their name and continue their traditions.

Britain, Poland, Ukraine. Then, as now, an incommunicable bond was sparked by conflict. After the war, five of the six men settled here as refugees. Franciszek Socha married a Scottish woman and returned to teaching. The film star Karol Dorwski died in London in 1980. Another settled in Bath.

Now, more than ever, it is vital we remember their sacrifice, and the shared connection, renewed once again, between our three peoples.

Sir Tim Laurence is Chairman of English Heritage. A new display on STS 43 at Audley End opens today.

Whitby Abbey

The impressive and ruinous abbey looms over Whitby, and it is not hard to see how it inspired Bram Stoker’s Dracula. These are the remains of the thirteenth century Benedictine abbey. However, the history of the site stretches much further back than this, including evidence of late Bronze Age settlement.

My own interest is on its Anglian history, of course. The name for the site at that time was Streaneshalch and it is referenced in Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English People as the home of Cædmon, our earliest English poet.

Cædmon’s Hymn was one of the first poems I translated when learning Old English. Living in Yorkshire and exploring the north east of England, I’ve had the opportunity to better contextualise some of what I’ve learned of Anglo-Saxon history.

Post link

Today we visited Whitby Abbey along the coast in North Yorkshire! Additional photos and a wee bit of history to follow.

Post link

FREE BOOK!

Slavery and the English Country House

Madge Dresser and Andrew Hann (eds.)

English Heritage, 2013

more FREE BOOKS from lascasbookshelf.tumblr.com

||| Publisher’s blurb |||

The British country house has long been regarded as the jewel in the nation’s heritage crown. But the country house is also an expression of wealth and power, and as scholars reconsider the nation’s colonial past, new questions are being posed about these great houses and their links to Atlantic slavery.

This book, authored by a range of academics and heritage professionals, grew out of a 2009 conference on ‘Slavery and the British Country house: mapping the current research’ organised by English Heritage in partnership with the University of the West of England, the National Trust and the Economic History Society. It asks what links might be established between the wealth derived from slavery and the British country house and what implications such links should have for the way such properties are represented to the public today.

In order to improve access to this research, a complete copy of the text is free to download from the left hand side of this page.

- Foreword

List of contributors

Acknowledgements

Notes on measurements

Introduction

1. Slave ownership and the British country house: the records of the Slave Compensation Commission as evidence - Nicholas Draper

2. Slavery and West Country houses - Madge Dresser

3. Rural retreats: Liverpool slave traders and their country houses - Jane Longmore

4. Lodges, garden houses and villas: the urban periphery in the early modern Atlantic world - Roger H Leech

5. Slavery’s heritage footprint: links between British country houses and St Vincent, 1814-34 - Simon D Smith

6. An open elite? Colonial commerce, the country house and the case of Sir Gilbert Heathcote and Normanton Hall - Nuala Zahedieh

7. Property, power and authority: the implicit and explicit slavery connections of Bolsover Castle and Brodsworth Hall in the 18th century - Sheryllynne Haggerty and Susanne Seymour

8. Atlantic slavery and classical culture at Marble Hill and Northington Grange - Laurence Brown

9. Slavery and the sublime: the Atlantic trade, landscape aesthetics and tourism - Victoria Perry

10. West Indian echoes: Dodington House, the Codrington family and the Caribbean heritage - Natalie Zacek

11. Contesting the political legacy of slavery in England’s country houses: a case study of Kenwood House and Osborne House - Caroline Bressey

12. Representing the East and West India links to the British country house: the London borough of Bexley and the wider heritage picture - Cliff Pereira

13. Reinterpretation: the representation of perspectives on slave trade history using creative media - Rob Mitchell and Shawn Sobers

Notes

Index

Post link

Fountains Abbey, England

photo©jadoretotravel

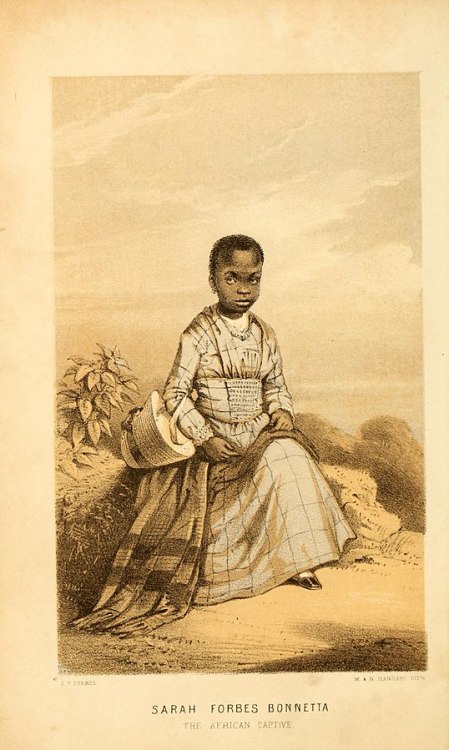

1. Sarah Forbes Bonetta by contemporary artist Hannah Uzor. Queen Victoria became a patron of freed slave Sarah Forbes Bonetta and raised her as a goddaughter. The painting is displayed by English Heritage at Osborne House in the Isle of Wight as part of

A new painting of Queen Victoria’s African goddaughter has gone on display as English Heritage said it would feature portraits of “overlooked” black figures connected with its sites.

Sarah Forbes Bonetta was sold into slavery aged five and presented as a “diplomatic gift” to Captain Frederick Forbes in 1850 and brought to England.

She then met Queen Victoria through the captain, who paid for her education.

The painting is on show at the Isle of Wight’s Osborne House to coincide withBlack History Month.

2. Portrait of Sara Forbes Bonetta, 1862 by photographer Camille Silvy, on which Hannah Uzor’s painting is based.

3. Lithograph of Forbes Bonetta, after a drawing by Frederick E. Forbes, from his 1851 book Dahomey and the Dahomans; being the journals of two missions to the king of Dahomey, and residence at his capital, in the year 1849 and 1850.

Sources: English Heritage via BBC, and wikipedia.

Oh my gosh it’s her!!! This!!!

Post link

Eltham Palace