#gut bacteria

Mouse study finds link between gut bacteria and neurogenesis

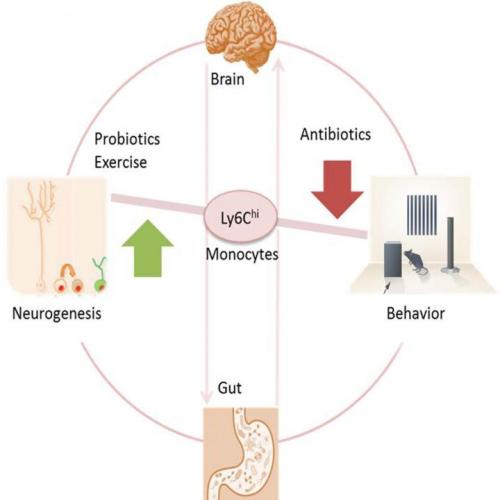

Antibiotics strong enough to kill off gut bacteria can also stop the growth of new brain cells in the hippocampus, a section of the brain associated with memory, reports a study in mice published May 19 in Cell Reports. Researchers also uncovered a clue to why– a type of white blood cell seems to act as a communicator between the brain, the immune system, and the gut.

“We found prolonged antibiotic treatment might impact brain function,” says senior author Susanne Asu Wolf of the Max-Delbrueck-Center for Molecular Medicine in Berlin, Germany. “But probiotics and exercise can balance brain plasticity and should be considered as a real treatment option.”

Wolf first saw clues that the immune system could influence the health and growth of brain cells through research into T cells nearly 10 years ago. But there were few studies that found a link from the brain to the immune system and back to the gut.

In the new study, the researchers gave a group of mice enough antibiotics for them to become nearly free of intestinal microbes. Compared to untreated mice, the mice who lost their healthy gut bacteria performed worse in memory tests and showed a loss of neurogenesis (new brain cells) in a section of their hippocampus that typically produces new brain cells throughout an individual’s lifetime. At the same time that the mice experienced memory and neurogenesis loss, the research team detected a lower level of white blood cells (specifically monocytes) marked with Ly6Chi in the brain, blood, and bone marrow. So researchers tested whether it was indeed the Ly6Chi monocytes behind the changes in neurogenesis and memory.

In another experiment, the research team compared untreated mice to mice that had healthy gut bacteria levels but low levels of Ly6Chi either due to genetics or due to treatment with antibodies that target Ly6Chi cells. In both cases, mice with low Ly6Chi levels showed the same memory and neurogenesis deficits as mice in the other experiment who had lost gut bacteria. Furthermore, if the researchers replaced the Ly6Chi levels in mice treated with antibiotics, then memory and neurogenesis improved.

“For us it was impressive to find these Ly6Chi cells that travel from the periphery to the brain, and if there’s something wrong in the microbiome, Ly6Chi acts as a communicating cell,” says Wolf.

Luckily, the adverse side effects of the antibiotics could be reversed. Mice who received probiotics or who exercised on a wheel after receiving antibiotics regained memory and neurogenesis. “The magnitude of the action of probiotics on Ly6Chi cells, neurogenesis, and cognition impressed me,” she says.

But one result in the experiment raised more questions about the gut’s bacteria and the link between Ly6Chi and the brain. While probiotics helped the mice regain memory, fecal transplants to restore a healthy gut bacteria did not have an effect.

“It was surprising that the normal fecal transplant recovered the broad gut bacteria, but did not recover neurogenesis,” says Wolf. “This might be a hint towards direct effects of antibiotics on neurogenesis without using the detour through the gut. To decipher this we might treat germ free mice without gut flora with antibiotics and see what is different.”

In the future, researchers also hope to see more clinical trials investigating whether probiotic treatments will improve symptoms in patients with neurodegenerative and psychiatric disorders.“We could measure the outcome in mood, psychiatric symptoms, microbiome composition and immune cell function before and after probiotic treatment,” says Wolf.

Post link

#TBT: Researchers have found, within the stomach of a prehistoric and well-preserved ice mummy (Oetzi the Iceman, to be exact), remains of his once-thriving gut bacteria! This means that the human microbiome has existed for millenia.

Although Oetzi’s been in the hands of scientists since 1991, researchers have only just now ventured into his stomach (largely because it was so shriveled they’ve had some trouble getting to it!), finding that it is “full of material.” In particular, they found what was presumably his last supper (meat from a deer and an alpine mountain goat), as well as DNA from a type of bacteria that lived in his gut - Helicobacter pylori.

According to a physician and microbiologist not related to the study, “Today, H. pylori can be found in about half of the world’s population. In people who have it, it’s the dominant organism in their stomach.”

WhileH. pylori has been known as a harmful pathogen, causing ulcers and stomach cancers, it also provides some benefits, such as protecting against acid reflux and asthma. The bacterium is probably most beneficial to scientists, who use “its evolution to map the paths of ancient populations as they moved across the globe.”

Read up on Oetzi (an interesting guy, really - he suffered from parasitic worms, Lyme disease, tooth decay, and joint problems, among other ailments, he has at least 19 living relatives somewhere in Austria, and he had 60-plus tattoos) and his gut bacteria at NPRorThe Atlantic.

Post link

“If you’re making resolutions for a healthier new year, consider a gut makeover.”

This is the starting sentence of a recent article in the New York Times, “A Gut Makeover for the New Year.” Given the recent uptick in research on the many effects the intestinal microbiota may have on human health–– our nutritional intake, our immune systems, and even diseases ranging from allergies to diabetes to depression–– a ‘makeover’ of these microbes could have a huge effect.

Much of the composition of the microbiome is established early in life, shaped by forces like your genetics and whether you were breast-fed or bottle-fed. Microbial diversity may be further undermined by the typical high-calorie American diet, rich in sugar, meats and processed foods. But a new study in mice and people adds to evidence that suggests you can take steps to enrich your gut microbiota. Changing your diet to one containing a variety of plant-based foods, the new research suggests, may be crucial to achieving a healthier microbiome.

Achieving this healthier microbiome, the article admits, will probably not be an easy feat, and will take an as-yet unspecified amount of time.

“The nutritional value of food is influenced in part by the microbial community that encounters that food,” said Dr. Jeffrey Gordon, the senior author of the new paper and director of the Center for Genome Science and Systems Biology at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. Nutritional components of a healthy diet have to be viewed from “the inside out,” he said, “not just the outside in.”

Dr. Gordon’s study, published in Cell Host & Microbe recently, looked into how diet affects this microbial community. Human gut bacteria was placed into sterile mice, who were fed various diets and analyzed. Among the most interesting findings were that a ‘calorie restricted’ group of mice (eating less than 1,800 calories a day of plant-based foods for two years) had a richer microbial community and more strains of “good” bacteria. Mice fed a ‘typical American diet” (3,000 calories a day featuring processed cheese, lunch meats, and few fruits and vegetables) did not fare quite as well.

For more information on how to reboot your gut for 2017 read the rest of the article in The New York Times here.

Post link

University of California researcher Bruce German has a lot to say on the subject of milk - specifically, human breast milk. While all mammals produce milk, the makeup of the substance differs from species to species, as one might expect, to cater to that species’ needs. But in researching the composition of human milk, German found a surprise.

From the New Yorker:

Every mammal mother produces complex sugars called oligosaccharides, but human mothers, for some reason, churn out an exceptional variety: so far, scientists have identified more than two hundred human milk oligosaccharides, or H.M.O.s. They are the third-most plentiful ingredient in human milk, after lactose and fats, and their structure ought to make them a rich source of energy for growing babies—but babies cannot digest them. When German first learned this, he was gobsmacked. Why would a mother expend so much energy manufacturing these complicated chemicals if they were apparently useless to her child?

The answer, researchers found, is that these H.M.O.s travel into the large intestine, where they are fed upon by a microbe called Bifidobacterium longum infantis, which will cause them to grow faster and more efficiently than any other gut bacteria. This process is motivated by evolution, and is beneficial to both the bacteria and the child.

As [B. infantis] digests H.M.O.s, it releases short-chain fatty acids, which feed an infant’s gut cells. Through direct contact, B. infantis also encourages gut cells to make adhesive proteins that seal the gaps between them, keeping microbes out of the bloodstream, and anti-inflammatory molecules that calibrate the immune system. These changes only happen when B. infantis feeds on H.M.O.s; if it gets lactose instead, it survives but doesn’t engage in any repartee with the baby’s cells. In other words, the microbe’s full beneficial potential is unlocked only when it feeds on breast milk.

There are a number of other ideas as to why such a vast and diverse number of H.M.O.s exist in humans over other mammals. Some scientists suggest that feeding B. infantis helps to stimulate brain growth; others note that it serves as a defense against pathogens. At a pediatric hospital in California, these microbes might be a solution to help nourish premature infants.

To learn more about H.M.O.s and Bifidobacteria, visit the full New Yorker article here.

Post link

when you kill me i drop a half-chewed piece of gum, my gut bacteria, a harmonica, and an unreasonable amount of xp