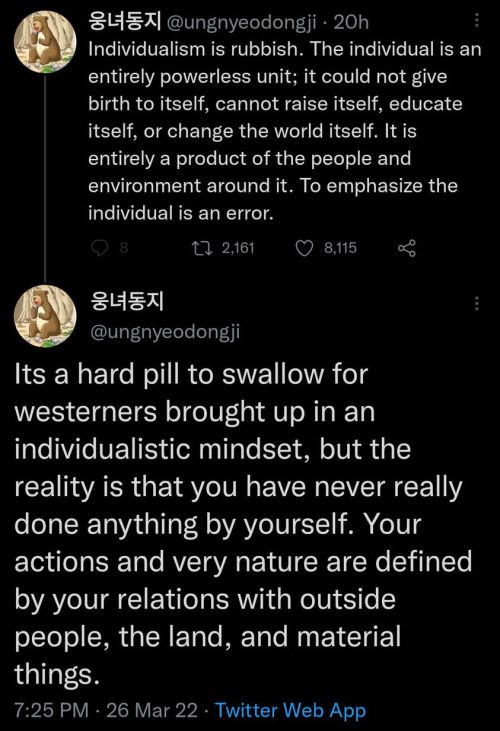

#individualism

“If you hate capitalism so much, go live in the forest!”: An Analysis of “Freedom,” “Individualism,” and the discursive model of “the Forest”

In one of my classes today we discussed some of the limitations which go along with the dominant narratives of “freedom” in the Global North (namely the U.S.), specifically in the context of Climate Change and the way that ideologies of freedom both feed into and work alongside ideologies of individualism in ways which prioritize the desires of individuals over communal needs and greatly undermine abilities to organize collectively. One student made a comment to the effect that people in the “First World” do not use the freedom they have, and in fact having freedoms becomes a source of anxiety for them; people don’t choose to enact freedom, for example, by pursuing opportunities to educate themselves. This is not intended either to perfectly/accurately articulate the student’s position (I am not attempting to misrepresent them, only acknowledging my own partial perspective and the assumption that they would have more to say to defend their position, otherwise (one hopes) they would not have said it in the first place), nor my desire to repeat the discussion in class; rather it is the product of my further meditation on the subject while sitting in traffic on the drive home.

To say that people in the “First World” do not use the freedom they have does several things: first it establishes the people of the Global North as “having” freedom (which further makes freedom something tangible and able to be possessed); second, it implies the Global South is not free; third it establishes that the Global North is not only free, but uniformly and universally free, and the Global South uniformly and universally “not” free; and fourth, it leaves “freedom” undefined in ways which make it difficult to understand what is intended by this sentiment. Is it freedom if you have real social and material consequences which make it difficult or even impossible for an individual to pursue certain options? The example I used in my response in class was something to the effect of: if I am against capitalism (which, of course, I am), am I complicit in capitalism because I have to perform wage labor in order to survive? And my coworkers who are even further disadvantaged, who have to work additional jobs and cannot attend school, where is their freedom to pursue education? Is it practical (or fair) to say that myself or my coworkers are anxious about the excess of freedom in our life, rather than the limitations?

Part of the response I received was a comment to the effect of “if you hate capitalism, you are free to go live in the forest.” Why is the forest freedom? Do “I” even have the freedom to live in the forest? Who does (or even might) have the freedom to live in the forest? What constitutes “living” in the forest? Let’s look first to the forest as a discursive figure, before discussing realities. As another student pointed out during discussion, the way the forest is so centralized to ideologies of freedom is because of an (over)privileging of Thoreau. In my opinion, it centers the idea of “freedom” in a lack of governmental, social, and, in this case, corporate intervention into one’s life; is this what freedom is? Perhaps, in hegemonic discourses. I would argue that there are ways in which the forest is a space of un-freedom: while, again in the discursive model, there is a lack of intervention by social/governmental/corporate forces, many of the same concerns which appear in social spaces will still exist, even if they are articulated in other ways. Let’s say you are living in this forest by yourself (the discursive model is an individualistic one, after all): you may be free from the social influences/restrictions which come from actively cohabiting with humans, but you are not free from the cultural framework you were raised in or from isolation from humans and let’s move away from anthropocentrism, anyway–you are still cohabiting with other animals, and there is a kind of social organization involved in this so are you really free from "society”? You are also controlled by the elements, by your access to food, housing/shelter, medical care, etc; this is not to say that these are not concerns outside of the forest, but to point out that many of the same concerns which limit freedoms outside of the forest will not evaporate once one has entered the discursive space of the forest, and some of these limitations may even be heightened.

So now let’s turn towards some of the realities of the forest: first of all, one must ask is this even a desirable space? Do I feel “free” because I “can” live in the forest? Am I happier with my subsistence living in the forest (presumably by myself; can I convince my friends and family to live in the forest? And am I still free if I have brought a human social order with me?) than I am with my city/suburban subsistence living? If we treat this as a viable form of freedom, how must we then consider the homeless, the unemployed? Are they “free” because they “operate” “outside” of capitalism? And is exclusion from the “benefits” of a system the same as operating outside of it anyway; and how do we know when it is one over the other, whether the person experiencing homelessness and unemployment feels it is a “choice” or an imposition? I will concede that many people do have escapist fantasies where they go live in the forest or on a small self-sustaining farm or in some other way are able to be free of the social constraints they experience. One thing I do want to add on this note is the fact that, especially in the context of climate change, this itself is a prioritization of individualism which disrupts abilities to collectivize, further privileges the desires of the individual and reifies the individual itself as a discursive figure. Moreover in an American context this fantasy has some deep underlying colonial roots (whose forest do you plan to live in by yourself? whose land will you be farming?) which fundamentally tie into manifest destiny-esc ideologies of land ownership and desirability. That being said, I will also concede that the US is a continued settler colony and there is no discourse of desire at the present time which can be removed from this criticism, and there cannot be while the US remains a settler colony.

Okay, so we’re moving forward on the basis that it is in fact desirable to live in the forest. Now let’s ask who can live in the forest, and on what terms. If we’re looking at the forest as a reality, you probably can’t actually live there. Many forests are private property, but even “public” land is government owned; you can only camp at a National Forest for fourteen days, for example. So the two options here would be to move constantly between forests or to risk the consequences of trespassing (whether on “private” or “public” lands). I do acknowledge, of course, that one could likely stay a good deal longer than two weeks at a National Forest (or longer than any set restriction placed on any other forest, private or public) by moving within the forest to avoid detection (or perhaps in some of the larger forests simply by setting up a stationary living situation camouflaged with the environment somewhere relatively remote), so my argument here is not that you could never live in a forest longer than two weeks, but rather that the forest is not a space of freedom from the government or corporations. These fantasies of isolated living still hinge heavily on land ownership which are inaccessible to many. Am I free if it’s only a matter of time before I am arrested for trespassing or poaching? The kinds of anxieties these uncertainties would generate certainly don’t stem from an abundance of options.

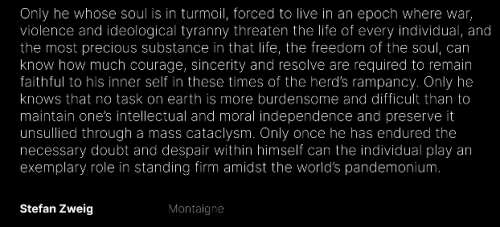

Finally we need to consider the accessibility of such a living arrangement: so going along with the idea that this is a desired lifestyle and that one has indefinite and unrestricted access to the space itself, we still need to consider who can actually live in this way. This not only means who has the kinds of knowledge necessary in order to survive (knowledge of hunting/fishing, butchery, agriculture, cooking, sewing, construction, etc), which many people who (are forced to) engage in urban/suburban modes of subsistence living do not have access to, but also intends to call into question the role of ability/disability. Are there wheelchair ramps in the forest? And, in the long term, what about medications? I am dependent on biweekly medication: does someone deliver my medication to The Forest or do I hike to the nearest city and hope the pharmacy accepts barter? When I have a day where I am physically unable to function due to pain and/or fatigue, do I (living by myself in the forest) call out sick to my garden, or to the river where I fish? This is not to say people with disabilities cannot or have not lived in the forest, or that they cannot/have not lived other kinds of rural lives; the inability to access certain kinds of medication has and does cause deaths, as have and do certain kinds of disabilities without access (to medical care, food, housing,etc), but communities are and historically have been able to work together to create more accessible conditions–this is just something missing from the hermit in the forest model. And to this end, I want to add that Thoreau himself, on whom this whole discursive model is based, did not live in the forest without support: he had friends and went into town and visited his mother and took home leftovers from dinner. Through my critique of “go live in the forest” as a discursive model of freedom, the point which I am ultimately trying to make is that if we choose to examine the anxieties we believe are generated by freedom, we need to consider first the perspective of those with too few options before the perspective of those with too many.

Meanwhile, in France….#20

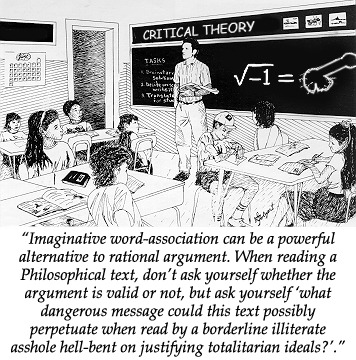

“The author’s claim that individuals are the ultimate units of moral concern must be rejected, as the occurrence of the word ‘individual’ makes it of course equivalent to methodological individualism, which of course invariably and in any possible context serves to perpetuate the individualist ideology of capitalism”

Post link

Be yourself; everyone else is already taken.

Oscar Wilde

The worst thing about capitalist culture is that it requires people recover, heal, suffer, cope, and struggle as individuals. Oppressions that naturally invoke community, cooperation, commonality–our ability to recognize ourselves with others, through and in others–are regulated via the urge/demand to struggle alone. We’re encouraged to find strength and solace in isolation. Ownership and property only further cultivate this order.

—Anne Fernihough, “Introduction,” The Rainbow by D. H. Lawrence (Penguin, 1995)

I didn’t have room to quote the above in my essay, just published yesterday, on Lawrence’s The Rainbow, but you can take it as my epigraph. In my treatment of the subject, I first suggest that a paradigmatic female modernist like Woolf, insofar as she was a modernist, was no less a partner in this “suppression…of political movements” (and the same goes for Stein, Barnes, Moore, Loy, and more, to varying degrees all non-leftists or even in some cases rightists). Then I go so far as to defend the instinct that won out here: the higher politics of the aesthetic over the low politics of mass movements with their designs on state power. Needless to say, this is a very timely prior instance of the same decoupling of bohemian from activist, of aesthetics from militancy, that we see today.

Speaking of all that, while mainstream elite culture is having a D. H. Lawrence moment, I’m surprised he’s not more present in the online extremist countercultures. He has that same Mishima quality, anticipating extremely-online male social outcasts, of being somehow perfectly poised between trans and Nazi, now dipping toward one side, now to the other, but somehow always keeping a precarious balance, in the art if not the life, the would-be mail-fisted fascist as tremulous adolescent girl. I think of how John Carey, in his roll-call of modernist fascism The Intellectuals and the Masses, pauses to exonerate Lawrence of his more troubling tendencies on the grounds that he was, in the end, just a sensitive soul who read Neech too early:

It must be stressed that Lawrence, for all his Nietzschean debts, was not like Nietzsche. The range and subtlety of his imagination went far beyond Nietzsche’s. The Nietzschean warrior ideal, and countenancing of cruelty, could only have seemed disgusting to Lawrence, who turns his characters not into warriors but into flowers. […] To cite such passages—and there are hundreds of them in Lawrence—and to contemplate the impossibility of Nietzsche having written them, is not just to emphasize that Lawrence was a poet and that Nietzsche was in some respects a desperately restricted and unfulfilled human being. It is also to contend that, for Lawrence, the stance of natural aristocrat, with its presuppositions of isolation and alienation, was adverse to all the promptings of his sympathetic imagination, which taught him to fuse and integrate.

The Rainbow is too long, but someone please make the NEETs read “Medlars and Sorb Apples” or “The Prussian Officer” at least. (Why does Mishima get all the attention? Strange that even fringe culture is dominated by the annoying presumption that if it’s translated it must be better.) In my essay I quote this passage from The Rainbow:

She never felt sorry for what she had done, she never forgave those who had made her guilty. If he had said to her, “Why, Ursula, did you trample my carefully-made bed?” that would have hurt her to the quick, and she would have done anything for him. But she was always tormented by the unreality of outside things. The earth was to walk on. Why must she avoid a certain patch, just because it was called a seed-bed? It was the earth to walk on. This was her instinctive assumption.

Here is my official comment, perhaps too Bloomian in its excited swoop through the canon:

Here we remember that Lawrence is the Englishman who put the gnostic-individualist literature of American Romanticism on modernism’s map. Ursula might be the daughter of Hester Prynne and Captain Ahab, her adventures chronicled by a prose Whitman.

My unofficial comment is that this is possibly my favorite paragraph from the novel because it expresses (I confess!) exactly how I felt as a child.

Post link

How America Fell into Toxic Individualism

Why I do not identify as an American in a nutshell. I hate the base individualism in this country.

Babies are socially accepted parasites.

When u read Ayn Rand 1 time

They’re not a parasite, they’re a potential investment

When you read Ayn Rand a dozen times