#isaac asimov

When the silence falls at last

And the clock tower rings no more

We watch the hourglass

Trapped like we were before

And we’ll lay awake in fear

Of the past days come again

But they’ll never find us here

Before they burn at this world’s end.

Aviators - They’ll Never Find Us

Post link

“Nunca permitas que el sentido de la moral te impida hacer lo que está bien”. Isaac Asimov

Post link

Book cover for Del Rey | Art Director: David G. Stevenson | Designer: Charles Brock | Published 2018

Post link

ALT

ALTIsaac Asimov

Un retrato de prueba para un proyecto en el que estoy trabajando.

Questions not only shape the nature of our knowledge, but deepen it as well. Isaac Asimov, prolific science-fiction author and biochemistry professor, was propelled by a curiosity to write across a variety of subjects: from astronomy to math to religion. Even today, the questions he asked continue to enrich our understanding of the human condition.

Post link

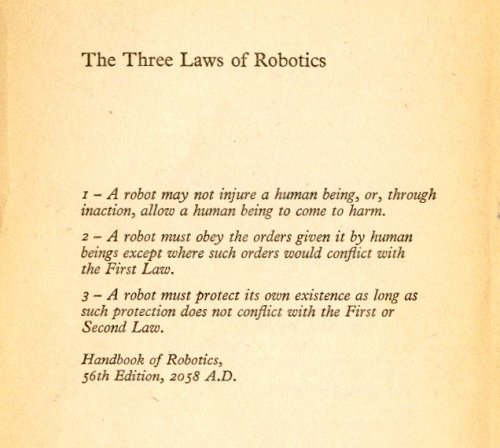

Is it OK to torture or murder a robot?

“We form such strong emotional bonds with machines that people can’t be cruel to them even though they know they are not alive. So should robots have rights?”

Post link

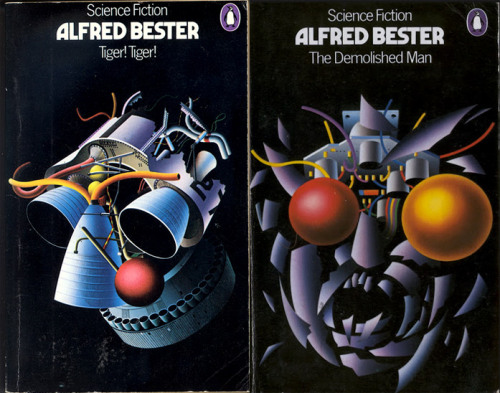

Fourth print of the cyberpunk zine Cheap Truth, 1983

Isaac Asimov (signed prints)© Iván García

Pencils, markers and digital.

Signed prints, martelec paper 240 gr.

3 Sizes:

- 148 x 210 mm (A5)

- 297x210 mm (A4)

- 420x297 mm (A3)

Now you can get all my prints at https://www.etsy.com/shop/IvanGshop

or message me

My sitessite-etsy-facebook-tumblr-instagram

Post link

By Isaac Asimov

The Skeptical Inquirer, Fall 1989, Vol. 14, No. 1, Pp. 35-44

I RECEIVED a letter the other day. It was handwritten in crabbed penmanship so that it was very difficult to read. Nevertheless, I tried to make it out just in case it might prove to be important. In the first sentence, the writer told me he was majoring in English literature, but felt he needed to teach me science. (I sighed a bit, for I knew very few English Lit majors who are equipped to teach me science, but I am very aware of the vast state of my ignorance and I am prepared to learn as much as I can from anyone, so I read on.)

It seemed that in one of my innumerable essays, I had expressed a certain gladness at living in a century in which we finally got the basis of the universe straight.

I didn’t go into detail in the matter, but what I meant was that we now know the basic rules governing the universe, together with the gravitational interrelationships of its gross components, as shown in the theory of relativity worked out between 1905 and 1916. We also know the basic rules governing the subatomic particles and their interrelationships, since these are very neatly described by the quantum theory worked out between 1900 and 1930. What’s more, we have found that the galaxies and clusters of galaxies are the basic units of the physical universe, as discovered between 1920 and 1930.

These are all twentieth-century discoveries, you see.

The young specialist in English Lit, having quoted me, went on to lecture me severely on the fact that in every century people have thought they understood the universe at last, and in every century they were proved to be wrong. It follows that the one thing we can say about our modern “knowledge” is that it is wrong. The young man then quoted with approval what Socrates had said on learning that the Delphic oracle had proclaimed him the wisest man in Greece. “If I am the wisest man,” said Socrates, “it is because I alone know that I know nothing.” the implication was that I was very foolish because I was under the impression I knew a great deal.

My answer to him was, “John, when people thought the earth was flat, they were wrong. When people thought the earth was spherical, they were wrong. But if you think that thinking the earth is spherical is just as wrong as thinking the earth is flat, then your view is wronger than both of them put together.”

The basic trouble, you see, is that people think that “right” and “wrong” are absolute; that everything that isn’t perfectly and completely right is totally and equally wrong.

However, I don’t think that’s so. It seems to me that right and wrong are fuzzy concepts, and I will devote this essay to an explanation of why I think so.

When my friend the English literature expert tells me that in every century scientists think they have worked out the universe and are always wrong, what I want to know is how wrong are they? Are they always wrong to the same degree? Let’s take an example.

In the early days of civilization, the general feeling was that the earth was flat. This was not because people were stupid, or because they were intent on believing silly things. They felt it was flat on the basis of sound evidence. It was not just a matter of “That’s how it looks,” because the earth does not look flat. It looks chaotically bumpy, with hills, valleys, ravines, cliffs, and so on.

Of course there are plains where, over limited areas, the earth’s surface does look fairly flat. One of those plains is in the Tigris-Euphrates area, where the first historical civilization (one with writing) developed, that of the Sumerians.

Perhaps it was the appearance of the plain that persuaded the clever Sumerians to accept the generalization that the earth was flat; that if you somehow evened out all the elevations and depressions, you would be left with flatness. Contributing to the notion may have been the fact that stretches of water (ponds and lakes) looked pretty flat on quiet days.

Another way of looking at it is to ask what is the “curvature” of the earth’s surface Over a considerable length, how much does the surface deviate (on the average) from perfect flatness. The flat-earth theory would make it seem that the surface doesn’t deviate from flatness at all, that its curvature is 0 to the mile.

Nowadays, of course, we are taught that the flat-earth theory is wrong; that it is all wrong, terribly wrong, absolutely. But it isn’t. The curvature of the earth is nearly 0 per mile, so that although the flat-earth theory is wrong, it happens to be nearly right. That’s why the theory lasted so long.

There were reasons, to be sure, to find the flat-earth theory unsatisfactory and, about 350 B.C., the Greek philosopher Aristotle summarized them. First, certain stars disappeared beyond the Southern Hemisphere as one traveled north, and beyond the Northern Hemisphere as one traveled south. Second, the earth’s shadow on the moon during a lunar eclipse was always the arc of a circle. Third, here on the earth itself, ships disappeared beyond the horizon hull-first in whatever direction they were traveling.

All three observations could not be reasonably explained if the earth’s surface were flat, but could be explained by assuming the earth to be a sphere.

What’s more, Aristotle believed that all solid matter tended to move toward a common center, and if solid matter did this, it would end up as a sphere. A given volume of matter is, on the average, closer to a common center if it is a sphere than if it is any other shape whatever.

About a century after Aristotle, the Greek philosopher Eratosthenes noted that the sun cast a shadow of different lengths at different latitudes (all the shadows would be the same length if the earth’s surface were flat). From the difference in shadow length, he calculated the size of the earthly sphere and it turned out to be 25,000 miles in circumference.

The curvature of such a sphere is about 0.000126 per mile, a quantity very close to 0 per mile, as you can see, and one not easily measured by the techniques at the disposal of the ancients. The tiny difference between 0 and 0.000126 accounts for the fact that it took so long to pass from the flat earth to the spherical earth.

Mind you, even a tiny difference, such as that between 0 and 0.000126, can be extremely important. That difference mounts up. The earth cannot be mapped over large areas with any accuracy at all if the difference isn’t taken into account and if the earth isn’t considered a sphere rather than a flat surface. Long ocean voyages can’t be undertaken with any reasonable way of locating one’s own position in the ocean unless the earth is considered spherical rather than flat.

Furthermore, the flat earth presupposes the possibility of an infinite earth, or of the existence of an “end” to the surface. The spherical earth, however, postulates an earth that is both endless and yet finite, and it is the latter postulate that is consistent with all later findings.

So, although the flat-earth theory is only slightly wrong and is a credit to its inventors, all things considered, it is wrong enough to be discarded in favor of the spherical-earth theory.

And yet is the earth a sphere?

No, it is not a sphere; not in the strict mathematical sense. A sphere has certain mathematical properties - for instance, all diameters (that is, all straight lines that pass from one point on its surface, through the center, to another point on its surface) have the same length.

That, however, is not true of the earth. Various diameters of the earth differ in length.

What gave people the notion the earth wasn’t a true sphere? To begin with, the sun and the moon have outlines that are perfect circles within the limits of measurement in the early days of the telescope. This is consistent with the supposition that the sun and the moon are perfectly spherical in shape.

However, when Jupiter and Saturn were observed by the first telescopic observers, it became quickly apparent that the outlines of those planets were not circles, but distinct ellipses. That meant that Jupiter and Saturn were not true spheres.

Isaac Newton, toward the end of the seventeenth century, showed that a massive body would form a sphere under the pull of gravitational forces (exactly as Aristotle had argued), but only if it were not rotating. If it were rotating, a centrifugal effect would be set up that would lift the body’s substance against gravity, and this effect would be greater the closer to the equator you progressed. The effect would also be greater the more rapidly a spherical object rotated, and Jupiter and Saturn rotated very rapidly indeed.

The earth rotated much more slowly than Jupiter or Saturn so the effect should be smaller, but it should still be there. Actual measurements of the curvature of the earth were carried out in the eighteenth century and Newton was proved correct.

The earth has an equatorial bulge, in other words. It is flattened at the poles. It is an “oblate spheroid” rather than a sphere. This means that the various diameters of the earth differ in length. The longest diameters are any of those that stretch from one point on the equator to an opposite point on the equator. This “equatorial diameter” is 12,755 kilometers (7,927 miles). The shortest diameter is from the North Pole to the South Pole and this “polar diameter” is 12,711 kilometers (7,900 miles).

The difference between the longest and shortest diameters is 44 kilometers (27 miles), and that means that the “oblateness” of the earth (its departure from true sphericity) is 44/12755, or 0.0034. This amounts to l/3 of 1 percent.

To put it another way, on a flat surface, curvature is 0 per mile everywhere. On the earth’s spherical surface, curvature is 0.000126 per mile everywhere (or 8 inches per mile). On the earth’s oblate spheroidal surface, the curvature varies from 7.973 inches to the mile to 8.027 inches to the mile.

The correction in going from spherical to oblate spheroidal is much smaller than going from flat to spherical. Therefore, although the notion of the earth as a sphere is wrong, strictly speaking, it is not as wrong as the notion of the earth as flat.

Even the oblate-spheroidal notion of the earth is wrong, strictly speaking. In 1958, when the satellite Vanguard I was put into orbit about the earth, it was able to measure the local gravitational pull of the earth–and therefore its shape–with unprecedented precision. It turned out that the equatorial bulge south of the equator was slightly bulgier than the bulge north of the equator, and that the South Pole sea level was slightly nearer the center of the earth than the North Pole sea level was.

There seemed no other way of describing this than by saying the earth was pear-shaped, and at once many people decided that the earth was nothing like a sphere but was shaped like a Bartlett pear dangling in space. Actually, the pear-like deviation from oblate-spheroid perfect was a matter of yards rather than miles, and the adjustment of curvature was in the millionths of an inch per mile.

In short, my English Lit friend, living in a mental world of absolute rights and wrongs, may be imagining that because all theories are wrong, the earth may be thought spherical now, but cubical next century, and a hollow icosahedron the next, and a doughnut shape the one after.

What actually happens is that once scientists get hold of a good concept they gradually refine and extend it with greater and greater subtlety as their instruments of measurement improve. Theories are not so much wrong as incomplete.

This can be pointed out in many cases other than just the shape of the earth. Even when a new theory seems to represent a revolution, it usually arises out of small refinements. If something more than a small refinement were needed, then the old theory would never have endured.

Copernicus switched from an earth-centered planetary system to a sun-centered one. In doing so, he switched from something that was obvious to something that was apparently ridiculous. However, it was a matter of finding better ways of calculating the motion of the planets in the sky, and eventually the geocentric theory was just left behind. It was precisely because the old theory gave results that were fairly good by the measurement standards of the time that kept it in being so long.

Again, it is because the geological formations of the earth change so slowly and the living things upon it evolve so slowly that it seemed reasonable at first to suppose that there was no change and that the earth and life always existed as they do today. If that were so, it would make no difference whether the earth and life were billions of years old or thousands. Thousands were easier to grasp.

But when careful observation showed that the earth and life were changing at a rate that was very tiny but not zero, then it became clear that the earth and life had to be very old. Modern geology came into being, and so did the notion of biological evolution.

If the rate of change were more rapid, geology and evolution would have reached their modern state in ancient times. It is only because the difference between the rate of change in a static universe and the rate of change in an evolutionary one is that between zero and very nearly zero that the creationists can continue propagating their folly.

Since the refinements in theory grow smaller and smaller, even quite ancient theories must have been sufficiently right to allow advances to be made; advances that were not wiped out by subsequent refinements.

The Greeks introduced the notion of latitude and longitude, for instance, and made reasonable maps of the Mediterranean basin even without taking sphericity into account, and we still use latitude and longitude today.

The Sumerians were probably the first to establish the principle that planetary movements in the sky exhibit regularity and can be predicted, and they proceeded to work out ways of doing so even though they assumed the earth to be the center of the universe. Their measurements have been enormously refined but the principle remains.

Naturally, the theories we now have might be considered wrong in the simplistic sense of my English Lit correspondent, but in a much truer and subtler sense, they need only be considered incomplete.

Taken from: http://chem.tufts.edu/answersinscience/relativityofwrong.htm

Super rare Home Video magazine (Jan. 1981) featuring Marilyn on the cover and a gorgeous two-page spread and interview inside .

Post link

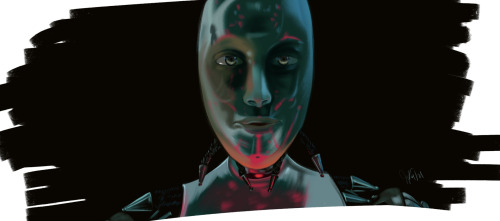

I, Robot is another one of my all time favorite films, and this part just stood out to me as a good study! Had a lot of fun with the lighting and I felt like I learned a lot when it comes to digitally painting screencaps in color, especially with blending ✌️

Post link

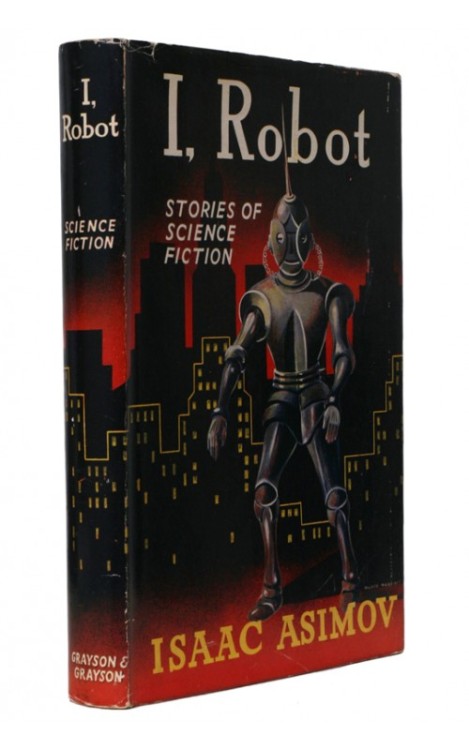

“I, Robot” was a short story by Eando Binder (Earl and Otto Binder) about a robot named Adam Link who was constructed by Dr. Charles Link. The story was published in Amazing Stories, January 1939. Several sequel stories featuring Adam Link would follow.

Over a decade later, Isaac Asimov’s famous collection of robot tales would be published under the title “I, Robot”. This was over the objections of Asimov who had read the Binders’ story before starting his own robot short story “Robbie”.

Adam Link would show up in two episodes of the sci fi anthology series The Outer Limits and again in the 1990s revival of the show. The illustration is from the January-February 1955 issue of EC Comics’ Weird Science-Fantasy, adapted by Al Feldstein and illustrated by Joe Orlando. Two more Adam Link tales would be featured in subsequent issues of the comic in that same year.

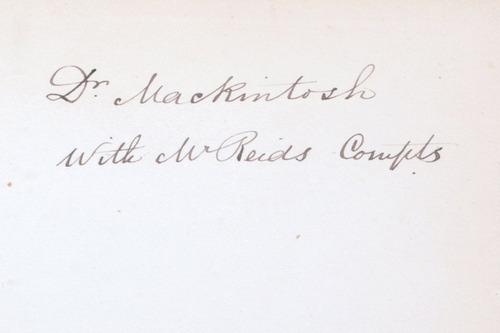

A new collector got in touch recently to ask our opinion on an inscribed book. He was concerned because the book was signed to someone else. I pointed out the various merits and flaws with the different types of signatures. It seemed apt thereafter to share this on our blog.

Signed or Inscribed

This is an oft mentioned argument. A signed book is one where the author has scrawled nothing but their name on the book. An inscribed book on the other hand usually carries the name of the recipient in the author’s hand [often an inscribed book will just carry a greeting without a name]. Of late there has been debate about the various merits of the two types of signature. I’ll outline below the merits of each.

A signed book

An inscribed book

An inscribed book is usually signed to someone else and carries their name. People often find this less than desirable because every time the owner examines the signature they are reminded that the book isn’t signed to them personally. This is just a facade of course, as a book purchased signed or inscribed has no connection with the purchaser anyway. But it is easy to see how the anonymous signature could be preferred. That being said, here at Hyraxia, we believe the more ink on the page the better. If a collector looks to buy only books signed without an inscription then they are often dismissing inscriptions that could have merit of their own; even a few brief words can give a deep insight into the author’s manner and make an ordinary book something special.

A book inscribed without a name.

Of greater significance is where an author signs without inscription by default. In these cases, such as with Graham Greene, an inscription is preferred. These signatures are both scarcer and more collectable as Greene generally inscribed books to people he knew.

The final point to consider is forgeries. A forger is less likely to risk exposure by writing an essay on the title page. That said, an expert forger will likely find it easier to dupe a buyer if they inscribe the book too. Either way, there is more room for error in an inscribed book than a signed book.

Presentation Copies

Presentation copies are often preferable to a regular signed copy particularly if signed by the author. Presentation copies are books signed and presented at the author’s behest, not the recipient’s request. This is significant because they are often scarcer, but also because there is an implicit, if somewhat forgotten or hazy, connection between the recipient and the author.

A presentation copy signed on behalf of the author

We mentioned above that presentation copies are preferred, with the caveat of them being signed by the author. Wealthier or busier authors would often have a secretary or publisher sign a presentation copy on the author’s behalf. One should always be cautious when considering a book signed ‘with the author’s compliments’ or similar. This is often autographed by someone else, but still collectable. Earlier books were often signed in this manner, seek advice from an antiquarian or rare bookseller if you’re unsure.

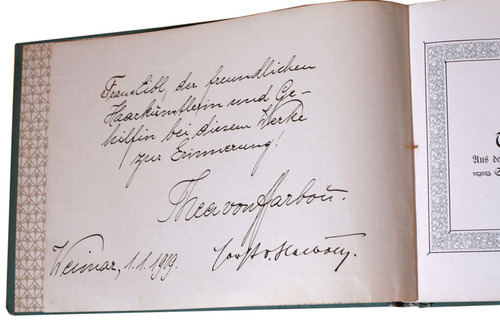

Association Copies

Anassociation copy is generally the best state of a signed book. An association copy is a book that has been signed by the author and subsequently owned by someone with whom there is an explicit connection to the book or author. These can be books signed by the author to a relative or friend, someone well known in particular other authors, people involved in the publication or people associated with the content of the book. It is always important to seek further provenance for association copies. A book signed “from Roald to Quentin” seems likely to be for Quentin Blake, but one must assess this based on evidence at hand – ask a Roald Dahl specialist if he ever signed books to Quentin Blake.

An association copy from Thea Von Harbou to her Hairdresser

An association copy from Asimov to Brunner

One can also find association copies that are unsigned, these are still desirable in their own right.

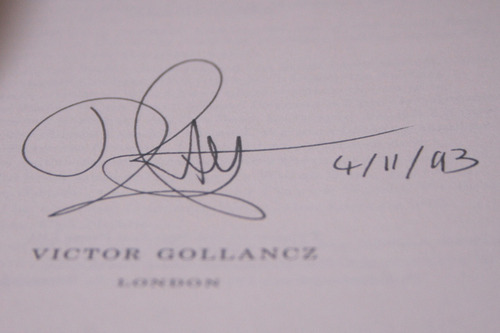

Dates

Often authors will write a date beneath their signature. It is generally accepted that a date closer to the publication date is preferred, primarily because this implies that the book was signed close to the publication date. Collectors prefer earlier signatures for two reasons: firstly, there’s an implicit connection to the book’s publication – in the same way first editions are collected, there’s a desirability to collect things in their earliest appearance; secondly, early signatures are often scarcer and more attractive as authors are less well-known and take a little more time and care over the signings.

A book signed and dated (in this case prior to publication)

Often one will see signatures pre-dating publication, these are usually where an author has signed a batch of books for a shop prior to publication, but there are some books where the pre-publication date signifies a presentation copy; the books have come from the author’s personal allowance.

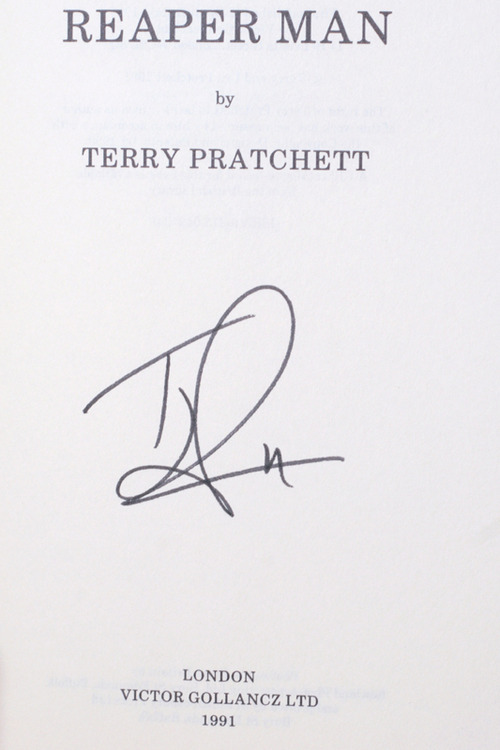

Signature Age

As authors age and attend more and more signings it’s not uncommon to see their signatures change, as noted above. The classic example is Terry Pratchett whose signature shifted from a full forename and surname in an attractive scrawl to what is essentially a symbol. We recently handled a collection of signed Pratchett books each of which held a contemporary signature and the progression was quite obvious. The early signatures are scarcer and indicative of a contemporary signing.

A recent Pratchett signature

An early Pratchett signature

Other than scarcity and desirability, one can also use signature ages to determine the authenticity of a signature. A copy of Pratchett’s latest book with an early signature is highly unlikely, and should be viewed as suspicious.

Bookplates

Bookplates come in a variety of forms and from a variety of sources. The least attractive arrangement is when a book is sold with a signature ‘laid in’. Oftentimes the signature will be on a scrap of paper, a publisher’s bookplate or a generic plate. There is no implicit connection between the signed paper and the particular copy of the book. This is simply something that the seller has put together to make the sale more attractive. This particular arrangement can, in our opinion, be worsened when the plate is pasted down by the previous owner.

A publisher’s bookplate (pasted in by the publisher)

Sellers do sometimes sell books and signatures in this format for the legitimate reason that they were purchased in that fashion and therefore the connection between the two is created through the provenance.

There is an exception to this rule when the book is published or sold in that particular state. For example, we have in stock a set of Philip K. Dick’s Collected Stories that were signed by way of a signature strip from a cheque. We also have a Murakami limited edition for which the publisher sent the author a group of plates to sign for the limited edition, which the publishers then pasted in. This is common with limited editions. An edge case is when a bookseller requests a number of plates from the author or publisher and then sells them on. We find that these are generally less preferable.

A book signed by way of a cheque (also a presentation copy)

Finally, bookplates are much easier to forge. There’s no risk of damaging a rare book and mistakes can just be binned. We’ve even seen high-quality photocopies of bookplates.

This is of course a matter of taste, but with regard to collectability one should opt for a book signed directly to the bound page or as published (in the case of tipped in leaves).

Scarcity

The final thing we’re going to look at is scarcity of a book in a signed state. If you find that you have the opportunity to be particular about the manner in which a given book is signed, then the chances are that signed copies are not particularly scarce on the ground. The phenomenon of ‘books with added value’ seems to be fairly recent borne most likely from the Harry Potter craze. Publishers wanted to create the next Harry Potter, collectors wanted to buy the next Harry Potter. The publishers printed first editions in huge quantities because the demand was there. Out of the high demand came a demand for collectable copies. Limited editions (both from the publisher and the bookshop) became more common, but also did books with various additions. By various additions we mean signatures from the cover artist, illustrators, and all manner of people associated with the book, additional sketches, dates under the signature and the recipient’s favourite line from within the book written by the author, ephemera from the publication including posters, bookmarks, postcards, bags and all manner of things. The publishers plough so much into marketing the book that the authors do huge tours where before there might be only a couple of signings. So the first editions are signed in huge numbers and are not rarities.

Signed, with a date and line from the book.

Our recommendation with these type of books is to err on the side of caution. You need to ensure that you’re buying for desirability and not for value because there’s a very good chance that you’ll be overpaying. One also has to understand how much value that embellishment actually adds to the book.

Quality

Byquality I mean the actual standard of the signature. Collectors will often prefer a signature written in a nice pen and not in a hurry. It’s easy to spot a sloppy signature.

Provenance

The stronger provenance you are offered the better chance you have of being secure in your purchase. Provenance doesn’t mean a good story to go with the book, it refers to evidence supporting the book’s reported history.

The important thing to note with provenance is to not be fooled by it. We were recently offered a signed T.S. Eliot book, the book was presented with a letter of provenance. It was a great story, the dates and association all lined up, there were associations with editors of magazines that Eliot wrote for and the names on the inscription all were accounted for – even the date had corroboration. However, the signature felt wrong as did other signatures for that the seller was offering. It was such a complex ruse too that holes appeared. The point is that it was so confidently presented that it was difficult not to believe the provenance.

Limited Editions from the publisher are pretty much guaranteed to be authentic, but are not always more valuable than signed first editions, particularly when printed in runs of 1000 or more. The provenance here is inherent.

A signed limited edition

Things such as ticket stubs, photos of the signing or promotional material can help, but these are not a sure fire way of guaranteeing an authentic signature. Of late, holograms have been used to authenticate a book as holograms are difficult to forge. While this pretty-much guarantees that you’re getting an authentic signature, it also suggests that the book was signed at a mass-signing, which to some extent reduces the desirability.

A hologram

Similarly, a history of the book at auction, doesn’t guarantee authenticity, but it does suggest that someone with a great deal of experience has looked at the signature and deemed it authentic. The same can be said with Certificates of Authenticity. These vary from a hand-written note guarantee to a full-blown holographic certificate from a reputable company. All the latter says is that someone has deemed the signature authentic and perhaps even guarantees that should it be proved inauthentic the buyer will get their money back. The problem is that it’s very difficult to prove a signature inauthentic. Often, experts in the trade will be asked their opinion to examine a purported forgery, which brings me back to my point of asking a member of the trade in the first place.

Another good bit of provenance is catalogue descriptions of the book’s previous sales, or receipts etc. from a previous seller. This chain of sales constitutes a good bit of provenance and again shows that experts have examined the book and deemed it authentic.

Manydealers will help you examine a signature, but the best way to attract these services is by becoming a customer and creating that relationship with the seller. You then have someone you can rely on for help and advice, who in turn can refer to their colleagues in the trade.

Isaac Asimov - I, Robot - Grayson and Grayson, 1952, UK First Edition

London, Grayson & Grayson, 1952. Hardback first edition and first impression. The book and jacket are near fine. Owner’s stamp to front end paper, owner’s plate to title page (covering owner’s stamp). Some soiling to page edges. Jacket is near fine also with a couple of neat closed tears, and a few creases. A very nice copy.

Post link

why cant i be normal whenever i see a handsome man im never like “wow good looking dude” im immediately like “wow this is exactly like when daneel olivaw”

yeah well this is what happens when you tell someone that Fox owns the rights to your identity Goyer

we need more foundation ads with demerzel for season 2, i want to be confronted with her incessantly i want everyone to have to deal with her

Hummin: I don’t suppose you saw Demerzel?

Hari: Who’s Demerzel?

Hummin: I saw Demerzel at a grocery store in the Imperial District yesterday. I told him how cool it was to meet him in person, but I didn’t want to be a douche and bother him and ask him for photos or anything. He said, “Oh, like you’re doing now?”

I was taken aback, and all I could say was “Huh?” but he kept cutting me off and going “huh? huh? huh?” and closing his hand shut in front of my face. I walked away and continued with my shopping, and I heard him chuckle as I walked off. When I came to pay for my stuff up front I saw him trying to walk out the doors with like fifteen Milky Ways in his hands without paying.

The girl at the counter was very nice about it and professional, and was like “Sir, you need to pay for those first.” At first he kept pretending to be tired and not hear her, but eventually turned back around and brought them to the counter.

When she took one of the bars and started scanning it multiple times, he stopped her and told her to scan them each individually “to prevent any electrical infetterence,” and then turned around and winked at me. I don’t even think that’s a word. After she scanned each bar and put them in a bag and started to say the price, he kept interrupting her by yawning really loudly.

Laura Birn + Foundation shirt

Laura Birn’s Demerzel Daneeling Absolute Olivaw

Bonus Kurosuke (which is canon imo)

reminder that daneel/demerzel based the design of the Imperial Palace off of Aurora ❤️